Validating Plant Gene Function: A Comprehensive Guide to VIGS and Knockout Studies

This article provides researchers and scientists with a detailed exploration of modern techniques for validating plant gene function, with a focus on Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) and gene knockout studies.

Validating Plant Gene Function: A Comprehensive Guide to VIGS and Knockout Studies

Abstract

This article provides researchers and scientists with a detailed exploration of modern techniques for validating plant gene function, with a focus on Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) and gene knockout studies. We cover foundational principles of post-transcriptional gene silencing, practical methodologies for implementing VIGS across diverse species including recalcitrant crops, and optimization strategies for enhancing silencing efficiency. The content includes direct comparisons between rapid VIGS screening and precise CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing, supported by case studies from recent research. Finally, we outline robust validation protocols and discuss the future integration of these tools for accelerating functional genomics and precision plant breeding.

The Science of Gene Silencing: From Natural Defense to Research Tool

Understanding Post-Transcriptional Gene Silencing (PTGS) as Plant Antiviral Defense

Post-Transcriptional Gene Silencing (PTGS) represents a fundamental RNA-based defense mechanism that plants employ to protect themselves against viral pathogens. This sequence-specific regulatory system recognizes and degrades aberrant or foreign RNA molecules, including viral genomes, providing an adaptive immune response that shares functional similarities with RNA interference (RNAi) pathways in other eukaryotes [1] [2]. The PTGS mechanism serves as a potent antiviral defense system because viral replication intermediates often generate double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) molecules, which the plant recognizes as "non-self" and targets for destruction [1]. This process effectively limits viral replication and spread within infected tissues, making PTGS a crucial component of plant innate immunity.

The significance of PTGS extends beyond its natural defensive role, as researchers have harnessed this mechanism to develop powerful functional genomics tools. Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS), which utilizes recombinant viral vectors to trigger targeted silencing of endogenous plant genes, has emerged as a particularly valuable application [3] [2]. The technology leverages the plant's own PTGS machinery to degrade both viral RNA and complementary host transcripts, enabling rapid functional characterization of genes involved in development, stress responses, and metabolic pathways [3] [4]. This review examines the molecular mechanisms of PTGS as an antiviral defense system, explores viral counter-defense strategies, and discusses experimental approaches for studying gene function through VIGS technology.

Molecular Mechanisms of Antiviral PTGS

The antiviral PTGS pathway operates through a well-orchestrated sequence of events that begins with detection of foreign RNA and culminates in sequence-specific degradation of target molecules. The process can be divided into distinct stages, each mediated by specific enzymatic complexes and signaling components.

Initiation: Detection and Dicing of Viral RNA

The PTGS pathway initiates when the plant detects double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) molecules, which are common replication intermediates for many viruses or can form through intramolecular base pairing within viral genomes [1] [5]. These dsRNA structures serve as potent signaling molecules recognized by host Dicer-like (DCL) enzymes, which belong to the RNase III family [1]. In Arabidopsis thaliana, four DCL enzymes have been identified, with DCL4 serving as the primary processor of virus-derived siRNAs, while DCL2 contributes to generating 22-nucleotide viral siRNAs and DCL3 produces 24-nucleotide variants involved in transcriptional silencing [1] [5]. The dicing activity of DCL enzymes cleaves long dsRNA molecules into small interfering RNA (siRNA) duplexes of 21-24 nucleotides in length, with the specific size distribution depending on the DCL enzyme involved [1].

Figure 1: Core Mechanism of Antiviral PTGS Pathway. The process begins with detection of viral dsRNA, progresses through siRNA-guided target cleavage, and amplifies through RDR6-dependent secondary siRNA production for systemic protection.

Effector Phase: RISC Assembly and Target Cleavage

Following dicing, the resulting virus-derived small interfering RNAs (vsiRNAs) are incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), which serves as the catalytic heart of the silencing machinery [1] [5]. The slicing core of RISC contains Argonaute (AGO) proteins, which bind the vsiRNAs and use them as guides to identify complementary viral RNA sequences [1]. Arabidopsis possesses ten AGO proteins, with AGO1 playing a central role in antiviral defense, supported by AGO2 and AGO7 under specific conditions [1]. The programmed RISC complex scans viral transcripts and cleaves those complementary to the loaded vsiRNA guide strand, effectively suppressing viral replication and gene expression [1]. This sequence-specific degradation prevents translation of viral proteins, thereby limiting infection progression and symptom development.

Amplification and Systemic Signaling

Plants have evolved an amplification mechanism to enhance and sustain the PTGS response against viral pathogens. This amplification involves RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RDRs), particularly RDR6, which use the cleavage products from primary RISC activity as templates to synthesize secondary dsRNA molecules [1] [5]. This process, stabilized by Suppressor of Gene Silencing 3 (SGS3), generates additional dsRNA substrates for DCL processing, resulting in production of secondary vsiRNAs that dramatically amplify the silencing signal [5]. Furthermore, the silencing signal spreads systemically throughout the plant, moving from cell to cell via plasmodesmata and over long distances through the vasculature, enabling establishment of antiviral immunity in distal tissues before viral invasion [5]. This systemic dimension of PTGS provides preemptive protection to non-infected tissues and represents a crucial adaptive feature of the plant immune system.

Viral Suppressors of RNA Silencing (VSRs)

In the ongoing evolutionary arms race between plants and viruses, viruses have developed sophisticated counter-defense strategies to overcome PTGS. Nearly all plant viruses encode viral suppressors of RNA silencing (VSRs)—multifunctional proteins that efficiently inhibit various steps of the antiviral silencing pathway [1] [5]. These suppressors employ diverse mechanisms to block PTGS, including dsRNA binding, siRNA sequestration, interference with AGO function, and inhibition of RDR activity [1]. The functional diversity of VSRs is remarkable, with even related viruses often employing structurally distinct proteins to achieve the same goal of silencing suppression [1].

Table 1: Characterized Viral Suppressors of RNA Silencing (VSRs)

| Viral Suppressor | Virus Origin | Mechanism of Action | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1/HC-Pro | Tobacco etch virus | Suppresses PTGS at posttranscriptional level; nuclear transcription unaffected [6] | Stable expression in transgenic plants reversed silencing of GUS transgene [6] |

| 2b | Cucumber mosaic virus | Inhibits antiviral RNAi; interacts with AGO proteins [5] | Patch assays show restored reporter expression when co-expressed [1] |

| P19 | Tombusvirus | Binds and sequesters siRNAs to prevent RISC loading [1] | Crystal structures show siRNA duplex binding; prevents systemic silencing [1] |

| γb | Poa semilatent virus | Multifunctional; inhibits PTGS and regulates replication [1] | Genetic studies demonstrate silencing suppression activity [1] |

The classic "patch assay" has been instrumental in identifying and characterizing VSR activities [1]. This experimental approach involves co-expressing a candidate viral protein alongside a silencing inducer (e.g., dsRNA hairpin) and a reporter gene target. When a functional VSR is present, it prevents the silencing mechanism from degrading the reporter mRNA, resulting maintained reporter expression and minimal siRNA accumulation [1]. In contrast, absence of a functional suppressor leads to efficient reporter degradation and abundant siRNA production. This assay system has revealed that VSRs typically target core components of the PTGS machinery, with many exhibiting multiple mechanisms of inhibition to ensure robust suppression of host defenses [1].

Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS): Harnessing PTGS for Functional Genomics

VIGS represents a powerful application of PTGS that enables researchers to silence endogenous plant genes by engineering viral vectors to carry host-derived sequences. When these recombinant viruses infect plants, the PTGS machinery targets both viral RNA and the corresponding host mRNA, resulting in specific knockdown of the plant gene [3] [2] [4]. This technology has emerged as a versatile reverse genetics tool that bypasses the need for stable transformation, allowing rapid functional characterization of genes in a wide range of plant species [3] [2].

VIGS Vector Systems and Applications

Several RNA and DNA viruses have been engineered as VIGS vectors, each with distinct advantages and host range specificities. Tobacco Rattle Virus (TRV)-based vectors have gained particular popularity due to their broad host range, efficient systemic movement, and ability to target meristematic tissues [3] [7]. Other commonly used vectors include Potato Virus X (PVX), Tobacco Mosaic Virus (TMV), Cucumber Green Mottle Mosaic Virus (CGMMV), and DNA viruses like Geminiviruses [3] [2] [4]. The selection of an appropriate vector depends on the host plant species, target tissue, and duration of silencing required.

Table 2: Comparison of Major VIGS Vector Systems

| Vector System | Virus Type | Host Range | Key Features | Demonstrated Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco Rattle Virus (TRV) | RNA virus | Broad (Solanaceae, Arabidopsis, etc.) | Efficient root & meristem invasion; mild symptoms [3] [7] | Silencing root development genes (IRT1, TTG1); nematode resistance (Mi) [7] |

| TRV-2b | Modified TRV | Extended range | Enhanced root tropism; improved meristem invasion [7] | Root architecture studies; nematode resistance pathways [7] |

| Cucumber Green Mottle Mosaic Virus (CGMMV) | RNA virus | Cucurbits (Luffa, cucumber, etc.) | Host-adapted for cucurbit species [4] | Tendril development (TEN); photobleaching phenotypes (PDS) [4] |

| Potato Virus X (PVX) | RNA virus | Solanaceous species | Strong systemic movement; robust silencing [2] | Disease resistance pathways; metabolic engineering [2] |

The practical implementation of VIGS involves cloning a fragment (typically 200-500 bp) of the target plant gene into a viral vector, introducing the construct into plants via Agrobacterium-mediated infiltration (agroinfiltration), mechanical inoculation, or other delivery methods, and monitoring for development of silencing phenotypes [3] [4]. Marker genes like Phytoene desaturase (PDS) and Cloroplastos Alterados 1 (CLA1) are commonly used to optimize VIGS protocols, as their silencing produces visible photobleaching phenotypes that confirm system functionality [8] [4]. For species with challenging leaf surfaces, such as Lycoris species with waxy coatings, modified infiltration methods like "leaf tip needle injection" have been developed to improve efficiency [8].

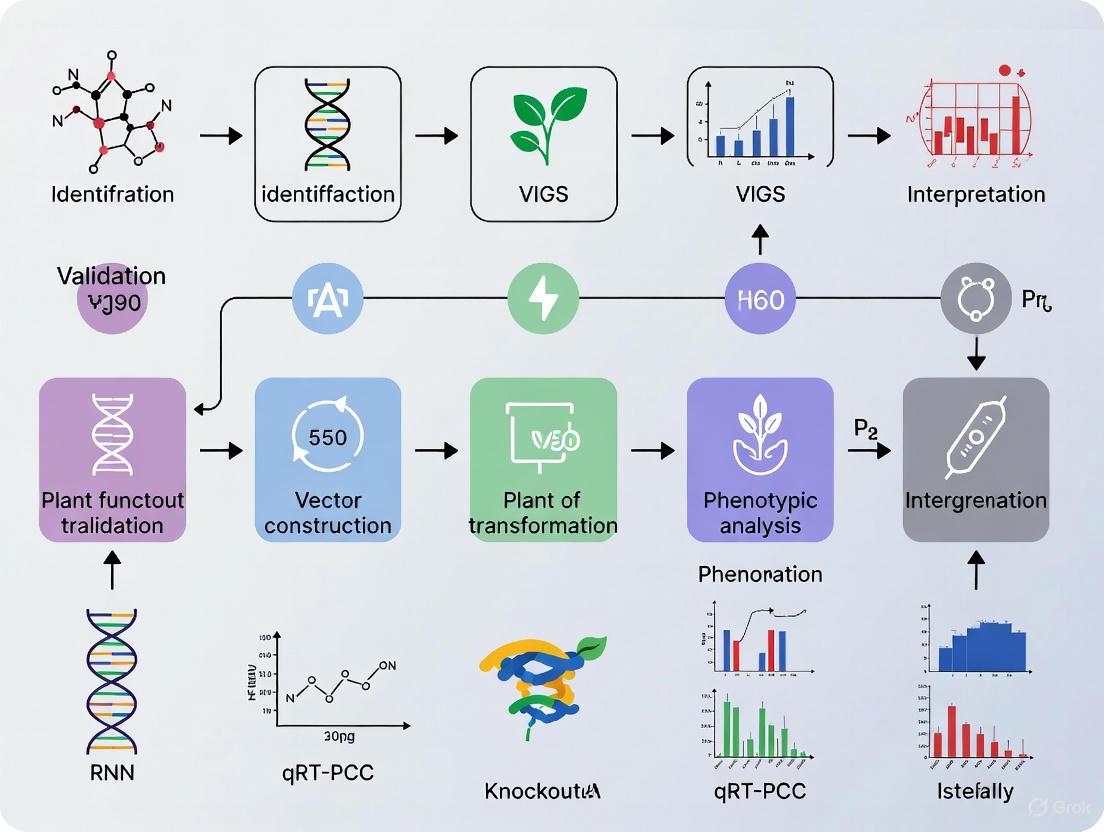

Figure 2: VIGS Experimental Workflow. The process involves constructing recombinant viral vectors, delivering them into plants, and analyzing resulting gene silencing phenotypes and molecular changes.

Experimental Validation and Research Applications

The functional validity of VIGS as a tool for gene characterization has been demonstrated across diverse plant species and biological processes. In pepper (Capsicum annuum L.), VIGS has enabled identification of genes governing fruit quality traits like color, biochemical composition, and pungency, as well as resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses [3]. In tomato, VIGS has been used to dissect disease resistance pathways and identify genes involved in defense signaling [2]. The technology has been particularly valuable for studying essential genes that would be lethal if constitutively disrupted, as VIGS produces transient knockdowns rather than permanent knockouts [2].

Recent methodological advances have further expanded VIGS applications. For root biology studies, a modified TRV vector retaining the 2b helper protein has shown dramatically improved efficiency in silencing genes in root tissues and meristems of Nicotiana benthamiana, Arabidopsis, and tomato [7]. This modified system enabled functional analysis of genes involved in root development (IRT1, TTG1, RHL1), lateral root-meristem function (RML1), and nematode resistance (Mi) [7]. In cucurbit species, CGMMV-based VIGS has been successfully established for ridge gourd (Luffa acutangula), silencing both marker genes (PDS) and developmental genes (TEN) involved in tendril formation [4]. These applications highlight how vector optimization and species-specific protocol development continue to broaden the utility of VIGS for plant functional genomics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for PTGS and VIGS Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Examples & Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| TRV-Based Vectors | Bipartite RNA virus system for VIGS | TRV1 (replicase/movement); TRV2 (capsid/target insert) [3] [7] |

| Marker Gene Constructs | VIGS efficiency validation | PDS (photobleaching); CLA1 (chloroplast development) [8] [4] |

| Agrobacterium Strains | Vector delivery via agroinfiltration | GV3101, others with appropriate antibiotic resistance [8] [4] |

| Viral Suppressor Clones | PTGS mechanism studies | P19, HC-Pro, 2b for suppression assays [1] [6] |

| siRNA Detection Reagents | Monitoring silencing efficiency | Northern blotting, small RNA sequencing protocols [1] [5] |

| AGO-Specific Antibodies | RISC complex immunoprecipitation | AGO1, AGO2 for studying slicing activity [1] [5] |

Post-Transcriptional Gene Silencing represents a sophisticated and highly adaptable antiviral defense system that plants have evolved to combat viral pathogens. The mechanistic understanding of this RNA-based immune response has not only revealed fundamental aspects of plant-virus interactions but has also enabled development of powerful research tools like VIGS that accelerate functional genomics. Despite viral counter-defense strategies through VSRs, the PTGS pathway remains a cornerstone of plant immunity, with ongoing research continuing to uncover novel regulatory components and signaling integrations. The experimental frameworks and reagent systems described herein provide researchers with robust methodologies for investigating gene function and dissecting molecular pathways in a wide range of plant species, thereby supporting advances in both basic plant science and applied agricultural biotechnology.

Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) is a powerful reverse genetics technology that leverages the plant's innate antiviral RNA silencing machinery to suppress endogenous gene expression. As a sequence-specific post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS) mechanism, VIGS allows researchers to rapidly investigate gene function by introducing recombinant viral vectors carrying target plant gene fragments, leading to systemic silencing and observable phenotypic changes [3]. The molecular foundation of VIGS lies in the conserved RNA interference (RNAi) pathway, where double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) triggers are processed into small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) that guide the degradation of complementary mRNA sequences [9] [10]. This mechanism represents an adaptive defense system that plants have evolved to protect their genomes from invading nucleic acids, including viral pathogens [10] [11].

The significance of VIGS in modern plant research stems from its advantages over traditional stable transformation methods. VIGS offers a transient, rapid, and cost-effective approach for gene function characterization without the need for labor-intensive stable transformation, making it particularly valuable for plant species that are recalcitrant to genetic transformation [3] [12]. Since its initial demonstration in 1995 using a Tobacco mosaic virus vector carrying a phytoene desaturase (PDS) gene fragment, VIGS has been adapted for functional gene analysis in over 50 plant species, including major crops like tomato, barley, soybean, and cotton [3]. This technology has become an indispensable tool for high-throughput functional screening, especially in species like pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) where stable transformation remains challenging and genotype-dependent [3].

Molecular Machinery of VIGS

Core Components and Mechanisms

The molecular mechanism of VIGS operates through a sophisticated protein-RNA machinery that can be divided into distinct biochemical stages. The process begins when viral replicative double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) forms are recognized by the plant's silencing apparatus. These dsRNA intermediates, generated during viral replication, serve as the initial substrates for the RNAi pathway [9] [12]. The plant's Dicer-like (DCL) enzymes, which are RNase III family nucleases, then process these long dsRNA molecules into small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) of specific lengths [9] [10]. In Arabidopsis thaliana, four DCL enzymes (DCL1-4) generate different siRNA size classes: 21 nucleotides (nt) for DCL1 and DCL4, 22 nt for DCL2, and 24 nt for DCL3 [10].

These virus-derived siRNAs are incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), a multiprotein effector complex that uses the siRNA as a guide to identify and cleave complementary viral RNA targets [9]. The core catalytic component of RISC is an Argonaute (AGO) protein, which possesses endonuclease activity ("slicer" activity) that executes the cleavage of target mRNAs [9] [11]. Arabidopsis possesses ten AGO proteins (AGO1-10) that show specialized functions in different silencing pathways [10]. The silencing effect becomes systemic through the movement of silencing signals between cells, allowing the entire plant to mount a defense against viral infection [3].

Table 1: Core Protein Components in Plant RNA Silencing Pathways

| Protein | Family | Function in VIGS | Specialized Roles |

|---|---|---|---|

| DCL1 | RNase III | Processes miRNA precursors | Generates 21-nt miRNAs from stem-loop structures |

| DCL2 | RNase III | Generates 22-nt siRNAs from viral dsRNA | Backup for DCL4; involved in secondary siRNA amplification |

| DCL3 | RNase III | Produces 24-nt heterochromatic siRNAs | Primarily involved in transcriptional silencing |

| DCL4 | RNase III | Primary processor of viral dsRNA | Generates 21-nt siRNAs for post-transcriptional silencing |

| AGO1 | Argonaute | Main effector for miRNA and siRNA function | Binds miRNAs and siRNAs to cleave complementary targets |

| AGO2 | Argonaute | Antiviral defense against certain viruses | Loads with viral siRNAs; enhanced expression upon infection |

| AGO7 | Argonaute | Binds specific miRNAs (e.g., miR390) | Involved in tasiRNA biogenesis |

| RDR6 | RNA-dependent RNA polymerase | Amplifies silencing signal | Converts cleaved RNAs into dsRNA for secondary siRNA production |

Visualizing the Core VIGS Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the key molecular steps in the VIGS mechanism, from viral infection to target gene silencing:

siRNA Biogenesis and Diversity

The siRNA population generated during VIGS exhibits considerable diversity in biogenesis pathways and functions. The major classes of small RNAs involved in silencing include:

Primary siRNAs: Derived directly from DCL processing of viral dsRNA replicative forms [9] [10]. These 21-24 nt molecules show asymmetric distribution along positive and negative viral RNA strands, with cleavage "hot spots" identified in tombusvirus infections [9].

Secondary siRNAs: Produced through an amplification mechanism involving RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RDRs). When primary RISC complexes cleave target RNAs, the cleavage products can be converted to dsRNA by RDR6 (in Arabidopsis), which is then processed by DCL proteins into secondary siRNAs [10]. This process, known as "transitivity," enables amplification and systemic spread of the silencing signal [10].

microRNAs (miRNAs): Endogenous small RNAs processed from stem-loop precursor transcripts that can also be incorporated into RISC complexes. While not directly involved in VIGS, miRNAs share common machinery components and can influence silencing efficiency [9] [10].

The biogenesis of these different small RNA classes involves specialized protein complexes. For instance, the production of trans-acting siRNAs (tasiRNAs) requires specific RNA-binding proteins like SGS3, which interacts with RDR6 and may shuttle between nucleus and cytosol to facilitate RNA export and siRNA production [10].

Experimental Approaches for VIGS Mechanism Analysis

Key Methodologies and Protocols

Studying the molecular mechanism of VIGS requires specialized experimental approaches that can capture the dynamic protein-RNA interactions and enzymatic processes involved. The following core methodologies have been developed to dissect VIGS mechanisms:

Recombinant Viral Vector Construction is the foundational step in VIGS experiments. For tombusvirus-based systems like CymRSV, researchers clone 190-300 bp target gene fragments into viral genomes downstream of reporter genes like GFP [9]. The viral vector is then transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 for plant delivery [12]. Optimal insert size and positioning within the viral genome significantly impact silencing efficiency, with studies using site-directed mutagenesis to create precise cloning sites [9].

Agrobacterium-Mediated Delivery (Agroinfiltration) involves growing recombinant Agrobacterium cultures to OD600 of 0.6-0.8 in YEP medium containing appropriate antibiotics, followed by resuspension in infiltration buffer (10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM MES, 200 μM AS) [12]. The bacterial suspension (OD600 0.8-1.0) is infiltrated into plant leaves using needleless syringes, typically targeting seedlings at the 4-6 leaf stage [9] [12]. Efficient delivery requires maintaining plants under high humidity with clear polyethylene covers for 24 hours post-infiltration [12].

Biochemical Analysis of RISC Complexes utilizes large-scale biochemical purification from plant tissues to isolate functional silencing complexes. The protocol involves homogenizing 100 mg of leaf tissue, followed by differential centrifugation to obtain cell extracts [9]. RISC complexes are purified through multiple chromatographic steps while monitoring for Ago-2 protein and RISC activity via Western blotting and nuclease assays [11]. Identification of associated proteins like VIG and dFXR (the Drosophila homolog of FMRP) is achieved through co-immunoprecipitation and RNAse treatment experiments [11].

High-Throughput Sequencing of Small RNAs provides comprehensive profiles of viral siRNAs. Researchers extract total RNA using Tri-reagent, then separate and detect small RNAs using 32P-labeled riboprobes or locked nucleic acid (LNA) oligonucleotide probes [9]. For precise mapping of cleavage sites, 3' rapid amplification of cDNA ends (3' RACE) sequencing is performed on 5 μg of total RNA ligated to 3'-end adapter oligonucleotides [9].

Table 2: Key Experimental Parameters for VIGS Analysis

| Parameter | Optimal Conditions | Impact on Results |

|---|---|---|

| Plant developmental stage | 4-6 leaf stage (Nicotiana benthamiana) | Younger plants show more efficient systemic silencing |

| Agroinfiltration OD600 | 0.8-1.0 | Higher OD can cause phytotoxicity; lower OD reduces efficiency |

| Post-infiltration temperature | 22-24°C constant | Elevated temperatures can enhance silencing spread but may increase non-specific effects |

| Time course analysis | 10-15 days post-inoculation | Early timepoints capture initiation; later timepoints show systemic effects |

| Tissue sampling | Separate local and systemic leaves | Distinguishes cell-autonomous from non-cell-autonomous silencing |

| siRNA detection method | High-resolution Northern blotting or small RNA-seq | Different sensitivity and quantification capabilities |

Visualizing the Experimental Workflow

The standard experimental pipeline for analyzing VIGS mechanisms involves both in vivo and in vitro approaches:

Key Research Reagents and Solutions

The following essential research materials are critical for successful investigation of VIGS mechanisms:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for VIGS Mechanism Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Composition/Specifications | Experimental Function |

|---|---|---|

| pTRV1 and pTRV2 Vectors | Bipartite Tobacco Rattle Virus system | Most versatile VIGS system for Solanaceae plants; TRV1 encodes replicase and movement proteins; TRV2 contains cloning site for target genes [3] |

| CymRSV-Cym19stop Mutant | Tombusvirus with defective p19 silencing suppressor | Unique system that allows strong VIGS activation in recovered leaves; enables analysis of RISC-mediated cleavage without suppressor interference [9] |

| CGMMV-based pV190 Vector | Cucumber green mottle mosaic virus vector | Specialized system for cucurbit species (cucumber, melon, Luffa); enables VIGS in previously challenging species [12] |

| Agrobacterium GV3101 | Strain with rifampicin and kanamycin resistance | Preferred strain for plant transformation; optimized for efficient T-DNA transfer in VIGS protocols [12] |

| Infiltration Buffer | 10 mM MgCl₂, 10 mM MES, 200 μM acetosyringone | Maintains Agrobacterium viability and promotes T-DNA transfer during leaf infiltration [12] |

| Tri-reagent Solution | Guanidine thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform mixture | Simultaneous extraction of RNA, DNA, and proteins from same sample; preserves small RNA species [9] |

| 32P-Labeled Riboprobes | In vitro transcribed RNAs with 32P-UTP | High-sensitivity detection of viral RNAs and siRNAs in Northern blot analyses [9] |

| LNA Oligonucleotide Probes | Locked Nucleic Acid-modified DNA oligos | Enhanced hybridization affinity for miRNA detection in Northern blots [9] |

| 3'-RACE Adapter Oligos | Pre-adenylated DNA/RNA chimeric oligonucleotides | Ligation to RNA 3' ends for amplification and sequencing of cleavage products [9] |

Comparative Analysis of VIGS Systems

Vector System Performance

Different viral vectors exhibit distinct performance characteristics in VIGS applications:

Table 4: Comparative Performance of Major VIGS Vector Systems

| Vector System | Host Range | Silencing Efficiency | Duration | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco Rattle Virus (TRV) | Broad (Solanaceae, Arabidopsis) | High in meristematic tissues | 3-5 weeks | Functional genomics in model plants; meristem gene silencing [3] |

| Tombusvirus (CymRSV) | Nicotiana benthamiana | Very high in recovered leaves | 2-4 weeks | Molecular mechanism studies; RISC activity analysis [9] |

| Cucumber Green Mottle Mosaic Virus (CGMMV) | Cucurbits (cucumber, Luffa, melon) | Moderate to high | 2-3 weeks | Gene function in cucurbit crops; fruit development studies [12] |

| Apple Latent Spherical Virus (ALSV) | Very broad (including legumes) | Variable between species | 4-8 weeks | Cross-species functional screening [12] |

| Bean Pod Mottle Virus (BPMV) | Soybean and other legumes | High in soybean | 3-6 weeks | Legume functional genomics [3] |

The TRV-based system remains the most widely adopted VIGS system due to its broad host range, efficient systemic movement, and ability to target meristematic tissues [3]. However, for specific plant families, specialized vectors like CGMMV for cucurbits have shown superior performance. Recent studies successfully applied CGMMV-VIGS to silence the tendril development gene TEN in Luffa acutangula, resulting in plants with shorter tendrils and higher nodal positions where tendrils appear [12]. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis confirmed significant reduction of TEN expression in silenced plants, demonstrating the efficacy of this system [12].

Molecular Efficacy Data

Experimental studies have generated quantitative data on the molecular efficacy of VIGS mechanisms:

Table 5: Quantitative Molecular Data on VIGS Efficacy

| Parameter | Experimental Measurement | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| siRNA size distribution | 21-24 nucleotides (primary), 21-22 nt (secondary) | Reflects activities of different DCL enzymes; 21-nt siRNAs most abundant [9] [10] |

| Cleavage efficiency | Minus-sense RNA strands cleaved more efficiently than plus-sense | Asymmetric RISC activity may reflect accessibility differences in structured viral RNAs [9] |

| Silencing suppression | p19 protein binds 21-nt ds-siRNAs with high affinity | Viral counter-defense mechanism prevents siRNA incorporation into RISC [9] |

| RISC complex size | ~500 kD molecular mass | Indicates multiprotein composition including AGO, VIG, and dFXR proteins [11] |

| Temporal progression | Maximum siRNA accumulation at 10-15 dpi | Correlates with recovery phenotype in suppressor mutant viruses [9] |

| Spatial distribution | Higher silencing efficiency in vascular tissues | Suggests directional movement of silencing signal [9] |

Research using the CymRSV silencing suppressor mutant (Cym19stop) revealed that viral RNA targeting occurs primarily through RISC-mediated cleavage rather than translational inhibition [9]. This conclusion was supported by sensor construct experiments showing sequence-specific cleavage of viral target sequences but no evidence of translational repression [9]. Strikingly, these studies identified that RISC-mediated cleavages do not occur randomly on the viral genome but instead show hot spots with asymmetric distribution along positive and negative viral RNA strands [9].

Technical Considerations and Optimization

Critical Factors Affecting VIGS Efficiency

Several technical factors significantly influence the success and interpretation of VIGS experiments:

Plant Genotype and Developmental Stage profoundly impact VIGS efficiency. Studies in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) reveal substantial genotype-dependent variation in silencing efficiency, with some cultivars showing robust systemic silencing while others exhibit only localized effects [3]. The optimal developmental stage for inoculation varies by species, but generally, younger plants (4-6 leaf stage for Nicotiana benthamiana) show more efficient systemic silencing [9] [12].

Environmental Conditions including temperature, humidity, and photoperiod must be carefully controlled. Maintaining constant temperature of 22-24°C following agroinfiltration significantly enhances silencing efficiency and reproducibility [9] [12]. High humidity immediately after infiltration is critical for Agrobacterium survival and T-DNA transfer, typically achieved by covering plants with clear polyethylene covers for 24-48 hours post-infiltration [12].

Agroinoculum Concentration requires precise optimization. While OD600 of 0.8-1.0 is commonly used, excessive Agrobacterium concentrations can cause phytotoxicity and non-specific effects, while insufficient concentrations reduce silencing efficiency [12]. The optimal concentration may need empirical determination for specific plant species and growth conditions.

Insert Design Parameters including length, sequence specificity, and positional effects within the viral vector significantly impact silencing efficiency. Fragments of 300-500 bp typically provide optimal specificity and efficacy, with GC content between 40-60% generally producing more consistent results [3] [12]. Bioinformatic analysis to avoid off-target silencing through sequence similarity searches is essential for accurate data interpretation.

Integration with Functional Genomics

VIGS serves as a powerful component in integrated functional genomics platforms, particularly when combined with other technologies. The marriage of VIGS with CRISPR/Cas9 systems enables rapid gene validation followed by precise genome editing [3] [13]. Similarly, integration with multi-omics approaches (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) provides comprehensive functional insights, as demonstrated in studies of manganese tolerance in mulberry where transcriptome analysis identified 811 differentially expressed genes under Mn stress, followed by VIGS validation of the MaCAX3 gene's role in Mn transport [14].

Recent advances in single-cell transcriptomic approaches further enhance the resolution of VIGS studies. Research in cotton used comparative single-cell transcriptomic mapping to identify a sea-island cotton-specific cell cluster, then employed VIGS to validate GbNF-YA7's role in pathogen resistance [15]. This integration of spatial resolution with functional validation represents the cutting edge of plant functional genomics.

The future of VIGS technology development points toward more sophisticated applications including virus-induced overexpression (VOX), virus-induced genome editing (VIGE), and host-induced gene silencing (HIGS) [12]. These advancements will further solidify VIGS as an indispensable tool for plant functional genomics and crop improvement programs.

For plant researchers, investigating gene function in recalcitrant species—those resistant to stable genetic transformation—presents a significant bottleneck. Traditional genetic engineering depends on efficient transformation and regeneration systems, which are absent in many legumes, woody perennials, and orphan crops [16] [17]. This limitation severely hinders functional genomics and the development of improved crop varieties. Fortunately, advanced transient techniques now enable rapid gene function analysis without the need for stable transformation. This guide compares three key approaches—Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS), Virus-Induced Genome Editing (VIGE), and Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated root transformation—providing researchers with actionable data and protocols to overcome these persistent challenges.

Technology Comparison & Performance Data

The following table objectively compares the core performance metrics of the three major technologies that bypass stable transformation.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Technologies Bypassing Stable Transformation

| Technology | Primary Function | Key Advantage | Typical Efficiency | Time to Result | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VIGS [18] [19] [20] | Post-transcriptional gene silencing (knock-down) | Rapid phenotype generation; no plant transformation required | 60-83% silencing efficiency (varies by protocol) | 7-28 days post-infiltration | Transient; potential recovery from silencing |

| VIGE [21] [22] | Targeted genome editing (knock-out) | Production of transgene-free, heritable edits; bypasses tissue culture | Varies by virus and host; rapidly improving | Initial edits in first generation; homozygosity requires progeny | Limited cargo capacity; potential host immune reaction |

| A. rhizogenes Hairy Root [21] | Root-specific transformation | Enables functional study of genes in root biology; highly efficient in susceptible species | High transformation rates in compatible species (e.g., citrus, strawberry) | 2-4 weeks for root emergence | Limited to root tissues; not whole-plant editing |

Quantitative data demonstrates that VIGS is the fastest method for initial gene characterization, achieving high silencing efficiency within weeks. For instance, a 2023 study on Styrax japonicus established VIGS systems with silencing efficiencies of 83.33% (vacuum infiltration) and 74.19% (friction-osmosis) [18]. In Striga hermonthica, VIGS efficiency reached 60.2% via agro-infiltration [19]. VIGE, while potentially slower to achieve homozygous lines, offers the unique advantage of creating stable, transgene-free mutations that are heritable, which is crucial for crop improvement programs [22].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

VIGS Protocol for Recalcitrant Species

The Tobacco Rattle Virus (TRV)-based VIGS system is widely applicable. The following workflow and protocol detail its implementation.

Figure 1: VIGS Experimental Workflow

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Vector Preparation: Clone a 300-500 bp fragment of the target gene (e.g., Phytoene desaturase (PDS) as a visual marker) into the multiple cloning site of the TRV2 vector. The construct is then introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strains like GV3101 [19] [20].

- Agrobacterium Culture: Grow the Agrobacterium containing TRV1 and the recombinant TRV2 vectors in LB or TY media with appropriate antibiotics until the optical density at 600 nm (OD₆₀₀) reaches approximately 1.0 [19].

- Cell Preparation: Pellet the bacterial cells by centrifugation and resuspend them in an infiltration buffer containing 10 mM MgCl₂, 10 mM MES, and 200 μM acetosyringone to a final OD₆₀₀ of 0.5-1.0. The optimal density should be determined empirically for the target species [18] [21].

- Plant Infiltration:

- Agro-infiltration: Use a needleless syringe to infiltrate the bacterial suspension into the abaxial side of leaves for dicot species [19].

- Vacuum Infiltration: For whole-plant infiltration or difficult tissues, submerge seedlings or explants in the bacterial suspension and apply a vacuum for 2-5 minutes, followed by a slow release [18] [21].

- Agro-drench: Apply the bacterial suspension directly to the soil around the plant base, which is less efficient but minimally invasive [19].

- Plant Incubation and Analysis: Maintain infiltrated plants in high-humidity conditions for 1-2 days, then transfer to normal growth conditions. Silencing phenotypes (e.g., PDS photo-bleaching) typically appear 7 to 14 days post-infiltration. Validation requires molecular analysis like RT-qPCR using stable reference genes to quantify knockdown efficiency [18].

VIGE Protocol for Transgene-Free Editing

VIGE adapts VIGS principles for CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- System Configuration:

- Method A (Virus Delivering sgRNA): Use a viral vector (e.g., TRV, BSMV) to deliver the sgRNA sequence into transgenic plants that constitutively express the Cas9 protein [21].

- Method B (Virus Delivering Cas9 and sgRNA): Use a single or multiple viral vectors to deliver both Cas9 and sgRNA. This is limited by the cargo capacity of the virus and requires compact Cas9 variants or split systems [22].

- Viral Vector Inoculation: Inoculate plants with the engineered virus using methods similar to VIGS (agro-infiltration, rub-inoculation). The virus spreads systemically, delivering editing components to meristematic cells, which is crucial for heritable edits [22].

- Harvest and Genotyping: Allow the virus to spread for several weeks. Harvest seeds from inoculated plants (T₀). Screen the subsequent T₁ generation for edited alleles using PCR/RE assays or sequencing, as edits integrated into germline cells will be heritable [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Bypassing Stable Transformation

| Reagent / Solution | Critical Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| TRV Vectors (pYL156, pYL279) [20] | RNA viral vector for inducing silencing; mild symptoms and robust systemic movement. | Preferred for Solanaceous species and Arabidopsis; efficient in meristems. |

| BSMV Vectors [20] | RNA viral vector for monocot species like barley and wheat. | Essential for silencing and editing studies in cereal crops. |

| Acetosyringone [18] [21] | Phenolic compound inducing Agrobacterium Vir genes; critical for T-DNA transfer. | Standard concentration of 200 μM in infiltration buffer is effective for many species. |

| Infiltration Buffer (MES/MgCl₂) [21] | Maintains pH and osmotic balance during Agrobacterium infiltration. | 10 mM MES (pH 5.2), 10 mM MgCl₂ provides optimal conditions. |

| Agrobacterium Strains (GV3101, K599) [21] [19] | Engineered disarmed strains for DNA delivery. GV3101 for VIGS/VIGE; K599 for hairy root induction. | K599 is a root-inducing (Ri) strain used for hairy root transformation. |

Bypassing stable transformation is no longer a barrier to functional genomics in recalcitrant plant species. VIGS stands out for its unparalleled speed in candidate gene validation, VIGE offers a direct path to heritable, transgene-free crop improvement, and A. rhizogenes-mediated transformation provides a unique window into root biology. The choice of technology depends entirely on the research objective: rapid knock-down, stable knock-out, or tissue-specific analysis. By adopting these transient and tissue culture-free methods, researchers can accelerate the characterization of gene function and the development of resilient crops, even in the most transformation-recalcitrant species.

Comparative Genomics and In Silico Prediction Models for Target Identification

In the modern genomics era, identifying causal genes and valid therapeutic targets requires sophisticated computational approaches that can process vast biological datasets. Comparative genomics and in silico prediction models have emerged as powerful methodologies for pinpointing critical genetic elements by analyzing evolutionary conservation, sequence patterns, and functional genomic data. These computational strategies are particularly valuable when integrated with experimental validation techniques like Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) and CRISPR knockout screens, creating a robust framework for confirming gene function in plant systems and beyond [23] [3].

The fundamental premise of comparative genomics lies in identifying genetic elements conserved across species, which often indicate essential functional roles. Meanwhile, advanced machine learning models now leverage these comparative insights to predict the functional consequences of genetic variants with increasing accuracy. When deployed within a structured workflow, these computational tools enable researchers to efficiently prioritize candidate genes for expensive and time-consuming experimental validation, dramatically accelerating the pace of biological discovery and therapeutic development [23] [24].

Key In Silico Prediction Models and Performance

Model Architectures and Methodologies

In silico prediction models for genomic target identification primarily utilize two deep learning architectures: Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Transformer-based models. CNN-based approaches, including SEI and TREDNet, excel at identifying local sequence patterns such as transcription factor binding sites and chromatin features through their hierarchical feature extraction layers. These models process DNA sequences by applying filters that detect motif-like patterns, with successive layers integrating these patterns into higher-order regulatory signals [24].

Transformer-based architectures, such as DNABERT and Nucleotide Transformer, employ self-attention mechanisms to capture long-range dependencies in genomic sequences. These models are pre-trained on large-scale genomic datasets through self-supervised learning, allowing them to develop contextual understanding of DNA sequence functionality before being fine-tuned for specific prediction tasks like identifying enhancer variants or causal single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) [24].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Recent standardized benchmarking studies have provided critical insights into the relative strengths of different model architectures for specific genomic tasks. The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of leading models based on comprehensive evaluations across multiple datasets:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Deep Learning Models for Genomic Predictions

| Model | Architecture | Best Application | Key Strengths | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEI | CNN | Predicting regulatory impact of SNPs in enhancers | Captures local motif-level features effectively | Superior for enhancer variant effect prediction [24] |

| TREDNet | CNN | Predicting regulatory impact of SNPs in enhancers | Models local sequence motifs and regulatory elements | Excellent for estimating enhancer regulatory effects [24] |

| Borzoi | Hybrid CNN-Transformer | Causal variant prioritization within LD blocks | Integrates local and long-range sequence context | Best for identifying causal SNPs in linkage disequilibrium blocks [24] |

| DNABERT-2 | Transformer | Capturing long-range dependencies | Self-attention mechanisms for sequence context | Benefits significantly from fine-tuning [24] |

| Nucleotide Transformer | Transformer | Cell-type-specific regulatory effects | Pre-trained on large-scale genomic sequences | Performance improves with task-specific fine-tuning [24] |

For plant genomics applications, these models face additional challenges including large repetitive genomes, rapid functional turnover, and limited experimental data compared to mammalian systems. Nevertheless, they show strong potential for predicting variant effects in both coding and regulatory regions, extending traditional quantitative trait loci (QTL) mapping approaches by generalizing across genomic contexts rather than fitting separate models for each locus [23].

Experimental Validation Frameworks

Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) in Plants

VIGS has emerged as a powerful reverse genetics tool for rapidly validating gene function in plants, leveraging the natural RNA silencing machinery of the host. The methodology involves engineering viral vectors to carry fragments of target plant genes, which when introduced into plants trigger sequence-specific degradation of complementary endogenous mRNAs through post-transcriptional gene silencing [3] [25].

The core VIGS workflow begins with vector selection and preparation, where researchers choose appropriate viral backbones (such as Tobacco Rattle Virus, Cucumber Green Mottle Mosaic Virus, or Turnip Crinkle Virus) and clone target gene fragments into the viral genome. The recombinant vectors are then introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens for plant transformation. For inoculation, Agrobacterium cultures carrying the VIGS constructs are infiltrated into plant tissues using needleless syringes, typically targeting leaves or cotyledons. After inoculation, plants are maintained under controlled environmental conditions to facilitate viral spread and silencing induction, with phenotypic effects typically observable within 2-4 weeks [12] [3] [25].

Table 2: Common VIGS Vectors and Their Applications in Plant Research

| Viral Vector | Virus Type | Host Range | Key Features | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco Rattle Virus (TRV) | RNA virus | Broad (Solanaceae, Arabidopsis) | Efficient systemic movement, mild symptoms | Functional genomics in pepper, tomato [3] |

| Cucumber Green Mottle Mosaic Virus (CGMMV) | RNA virus | Cucurbits (Luffa, cucumber) | Strong silencing in cucurbit species | Gene function studies in Luffa species [12] |

| Turnip Crinkle Virus (TCV) | RNA virus | Arabidopsis | Single RNA genome, high viral titer | Simultaneous silencing of multiple genes [25] |

| Apple Latent Spherical Virus (ALSV) | RNA virus | Broad (including cucurbits) | Mild or no symptoms | Silencing in multiple cucurbit species [12] |

Recent innovations in VIGS technology include the development of multiplex silencing vectors capable of simultaneously targeting multiple genes. For instance, researchers have engineered TCV-derived vectors that incorporate both a visual marker (e.g., phytoene desaturase, PDS) and additional target gene fragments, enabling preliminary assessment of silencing penetrance through visible photobleaching while studying genes of interest [25].

CRISPR/Cas9 Knockout Screens

CRISPR/Cas9-based functional screens represent a complementary approach to VIGS for target validation, particularly in systems where viral vectors are unsuitable. A notable advancement in this domain is the development of virus-free CRISPR screening methodologies that utilize plasmid-based sgRNA libraries coupled with whole-genome sequencing (WGS) for direct identification of causal mutations [26].

The experimental protocol involves several key steps. First, researchers design and synthesize a comprehensive sgRNA library targeting the protein-coding genes of interest, typically incorporating three sgRNAs per gene to ensure complete coverage. These plasmid libraries are co-transfected with a Cas9-expression plasmid into target cells, which are then subjected to selective pressures such as cytotoxic drugs or viral infection. Cells lacking key factors essential for survival under these conditions proliferate, while susceptible cells die. Genomic DNA from surviving cells is isolated and subjected to whole-genome sequencing to directly identify CRISPR/Cas9-induced causal mutations, bypassing statistical estimation approaches used in traditional lentiviral screens [26].

This approach has successfully identified both known and novel genes essential for viral infection in human cells, including the poliovirus receptor (PVR) and sialic acid biosynthesis genes (ST3GAL4) critical for enterovirus D68 infection. The methodology offers the distinct advantage of directly confirming causal mutations through WGS rather than relying on statistical enrichment of sgRNA sequences [26].

Integrated Workflows for Target Identification

Computational-Experimental Pipeline

Successful target identification requires careful integration of computational predictions with experimental validation. The workflow below illustrates the logical relationship between different stages of target identification:

Subtractive Genomics for Therapeutic Target Identification

In biomedical applications, subtractive genomics has emerged as a powerful computational strategy for identifying therapeutic targets in pathogenic organisms. This approach involves systematically comparing pathogen and host genomes to identify essential proteins in the pathogen that lack homologs in the host, thereby minimizing potential side effects from cross-reactivity [27].

The standard workflow begins with core proteome analysis to identify conserved proteins across multiple pathogen strains, followed by essentiality prediction using databases of essential genes. Non-essential genes and those with significant homology to host proteins are filtered out, leaving a subset of potential targets. Subsequent metabolic pathway analysis identifies proteins involved in pathogen-specific pathways, while subcellular localization predictions prioritize cytoplasmic targets for antibacterial development. Finally, druggability assessment evaluates the potential of shortlisted proteins to bind drug-like molecules with high affinity [27].

This methodology has successfully identified novel drug targets in multiple pathogens, including two proteins (B5ZC96 and B5ZAH8) in Ureaplasma urealyticum that show promise as therapeutic targets without significant homology to human proteins [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Genomic Target Identification and Validation

| Reagent/Tool | Category | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| sgRNA Library | CRISPR Screening | Targets multiple genes for knockout | Genome-wide knockout screens [26] |

| Cas9 Expression Plasmid | CRISPR Screening | Provides DNA cleavage function | Co-transfection with sgRNA libraries [26] |

| TRV-Based VIGS Vectors | Plant Functional Genomics | Induces transient gene silencing | High-throughput gene validation in plants [3] |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 | Plant Transformation | Delivers genetic material into plants | VIGS vector delivery [12] |

| Whole Exome Sequencing Platforms | Genomics | Identifies coding region variants | Target discovery and validation [28] |

| Deep Learning Models (SEI, TREDNet) | Bioinformatics | Predicts regulatory variant effects | Prioritizing causal SNPs [24] |

The integration of comparative genomics, sophisticated in silico prediction models, and robust experimental validation frameworks has created a powerful paradigm for target identification across biological systems. As deep learning architectures continue to evolve and experimental methods become more precise, this integrated approach will undoubtedly accelerate the pace of discovery in both basic plant science and therapeutic development. The future of target identification lies in increasingly sophisticated computational models that can accurately predict gene function and variant impact across diverse biological contexts, coupled with high-throughput experimental methods that can rapidly validate these predictions at scale.

Virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) has emerged as a powerful reverse genetics technology for rapidly characterizing gene functions in plants. This technology leverages the plant's innate antiviral RNA silencing defense mechanism to achieve sequence-specific downregulation of target genes without the need for stable genetic transformation. For cucurbit crops—economically important fruits and vegetables worldwide—functional genomic studies have been historically impeded by laborious and inefficient transformation protocols. The development of viral vectors capable of inducing gene silencing in cucurbits therefore represents a critical advancement for high-throughput gene function validation in these species. Among the various viral vectors available, Tobacco Rattle Virus (TRV), Cucumber Green Mottle Mosaic Virus (CGMMV), and Cucumber Fruit Mottle Mosaic Virus (CFMMV) have shown particular utility. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these three essential viral vectors, focusing on their host ranges, silencing efficiencies, and experimental applications to inform selection for functional genomics research.

Vector Origins and Genomic Features

Tobacco Rattle Virus (TRV)

TRV is a bipartite RNA virus belonging to the genus Tobravirus. Its genome consists of two RNA segments: RNA1 encoding replication and movement proteins, and RNA2 encoding the coat protein and other non-essential proteins that can be replaced with host gene fragments for VIGS. TRV has been widely adopted as a VIGS vector due to its broad host range, high silencing efficiency, and ability to induce long-lasting silencing effects in many plant species [29] [30]. The TRV-based VIGS system has been successfully established in tea plants (Camellia sinensis), where it silenced the CsPOR1 (protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase) gene, resulting in characteristic photobleaching phenotypes, and the CsTCS1 (caffeine synthase) gene, leading to a significant reduction in caffeine content [29].

Cucumber Green Mottle Mosaic Virus (CGMMV)

CGMMV is a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the genus Tobamovirus. Its genome of approximately 6.4 kb contains four open reading frames encoding replication-associated proteins, a movement protein (MP), and a coat protein (CP) [31] [32]. CGMMV-based VIGS vectors have been developed by inserting multiple cloning sites or duplicating the CP subgenomic promoter to accommodate foreign gene fragments [31]. CGMMV naturally infects cucurbit plants and has been engineered as an effective VIGS vector for several cucurbit species, demonstrating mild viral symptoms and persistent silencing effects that can last for over two months [31] [30].

Cucumber Fruit Mottle Mosaic Virus (CFMMV)

CFMMV is also a member of the genus Tobamovirus with genomic organization similar to CGMMV. Recent vector development efforts have optimized CFMMV for VIGS applications by incorporating the Araujia mosaic virus (ArjMV) MP gene, which significantly enhanced its silencing efficiency and stability in cucurbit hosts [30]. The improved CFMMV vector achieves higher silencing efficiency and longer duration of gene silencing effects compared to earlier versions, making it particularly valuable for functional studies in cucurbits [30].

Comparative Host Range and Silencing Efficiency

Table 1: Host Range Comparison of TRV, CGMMV, and CFMMV VIGS Vectors

| Plant Species | TRV | CGMMV | CFMMV | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nicotiana benthamiana | Effective [29] | Effective [31] | Information Missing | CGMMV vector with duplicated CP subgenomic promoter (pV190) caused milder symptoms than wild-type virus [31] |

| Cucumber (Cucumis sativus) | Effective [30] | Effective [31] [4] | Effective [30] | CGMMV vector induced photobleaching by silencing PDS; TRV required special agroinfiltration solution [31] [30] |

| Watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) | Effective [30] | Effective [31] [4] | Effective [30] | CGMMV-based silencing persisted for over two months; CFMMV silenced genes related to male sterility [31] [30] |

| Melon (Cucumis melo) | Effective [30] | Effective [31] | Information Missing | TRSV and ALSV vectors have also been successfully used [30] |

| Bottle Gourd (Lagenaria siceraria) | Information Missing | Effective [31] [4] | Information Missing | CGMMV vector effectively silenced PDS gene [31] |

| Ridge Gourd (Luffa acutangula) | Information Missing | Effective [4] | Information Missing | CGMMV-VIGS system successfully silenced PDS and TEN genes, affecting tendril development [4] |

| Tea (Camellia sinensis) | Effective [29] | Information Missing | Information Missing | TRV-mediated silencing of CsPOR1 and CsTCS1 achieved with vacuum infiltration [29] |

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of VIGS Vectors in Cucurbit Species

| Vector | Silencing Duration | Key Advantages | Reported Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRV | Long-lasting [29] | Wide host range beyond cucurbits; Established protocols | May require optimization of infection methods for different cucurbits [30] |

| CGMMV | Over 2 months [31] | Natural cucurbit pathogen; High efficiency in multiple species; Mild symptoms with optimized vectors | Silencing efficiency varies with insert size and orientation [31] |

| CFMMV | Long-lasting [30] | High efficiency with optimized vector; Effective for floral trait studies | Limited application reports compared to other vectors [30] |

| TrMMV | Persistent [33] | Broad efficacy across cucurbits; Particularly high efficiency in C. melo; Useful for floral traits | Newer vector with less established protocols [33] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

TRV-Mediated VIGS Protocol

The TRV-VIGS system typically employs a two-component vector system (pTRV1 and pTRV2). For tea plants, researchers have successfully implemented the following protocol [29]:

- Vector Construction: Clone target gene fragments (e.g., CsPOR1 or CsTCS1) into the pTRV2 vector.

- Agrobacterium Preparation: Transform recombinant pTRV2 and pTRV1 into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strains such as GV3101.

- Plant Inoculation: Mix bacterial suspensions containing pTRV1 and recombinant pTRV2 in a 1:1 ratio, then infiltrate into plants using vacuum infiltration or syringe infiltration.

- Phenotype Observation: Silencing phenotypes typically appear within 2-4 weeks post-inoculation.

In tea plants, this approach achieved approximately 75% silencing efficiency for CsPOR1, resulting in obvious photobleaching symptoms, and significantly reduced CsTCS1 expression, leading to a 6.26-fold decrease in caffeine content [29].

CGMMV-Based VIGS Protocol

The CGMMV-VIGS system has been optimized for cucurbit species including cucumber, watermelon, and ridge gourd [31] [4]:

- Vector Design: Develop CGMMV derivatives (e.g., pV190) with duplicated CP subgenomic promoters and BamHI cloning sites.

- Insert Cloning: Clone target gene fragments (e.g., PDS or TEN) in sense orientation into the vector.

- Agroinfiltration: Introduce recombinant vectors into Agrobacterium strain GV3101 and infiltrate into cotyledons or true leaves of seedlings.

- Efficiency Optimization: Use fragments of 150-300 bp for optimal silencing efficiency, with hairpin structures potentially enhancing silencing.

This system has successfully silenced the TEN gene in ridge gourd, resulting in altered tendril development with higher nodal positions of tendril appearance and shorter tendril length [4].

Impact of Insert Size on Silencing Efficiency

Research with the Trichosanthes mottle mosaic virus (TrMMV) VIGS system, a related tobamovirus, demonstrated that insert sizes between 90-400 bp can induce effective silencing, with 150 bp fragments showing particularly high efficiency in Cucumis sativus [33]. Similar size dependencies have been observed for CGMMV-based vectors, where fragments of 150-300 bp achieved optimal silencing [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for VIGS Experiments in Cucurbits

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Purpose | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| VIGS Vectors | Delivery of target gene fragments into host plants | pTRV1/pTRV2 (TRV), pV190 (CGMMV), pCF93 (CFMMV) [29] [31] [30] |

| Agrobacterium Strains | Delivery of viral vectors into plant cells | GV3101, EHA105 [33] [4] |

| Marker Genes | Visual assessment of silencing efficiency | PDS (photobleaching), POR1 (chlorophyll synthesis), Su (chlorophyll biosynthesis) [33] [29] [31] |

| Infiltration Buffers | Facilitating Agrobacterium entry into plant tissues | 10 mM MgCl₂, 10 mM MES, 200 μM AS [4] |

| Detection Primers/Probes | Confirming viral infection and silencing efficiency | Coat protein, movement protein, or replicase-specific primers [34] |

TRV, CGMMV, and CFMMV each offer distinct advantages as VIGS vectors for plant functional genomics research. TRV provides the broadest host range, extending beyond cucurbits to species like tea plants, making it suitable for comparative studies across diverse plant families. CGMMV demonstrates superior performance in natural cucurbit hosts, with persistent silencing effects and mild symptom development in optimized vectors. CFMMV represents a specialized tool for cucurbits, particularly valuable for studying reproductive development and traits when using recently enhanced versions. Vector selection should be guided by target host species, experimental timeframe, and specific research objectives. For cucurbit-specific studies, CGMMV and CFMMV generally offer more reliable and efficient silencing, while TRV remains the vector of choice for broader host ranges or when working with non-cucurbit species. Continuing vector optimization, particularly in delivery methods and insert stability, will further enhance the utility of these tools for high-throughput functional genomics in recalcitrant plant species.

Practical Implementation: From Vector Design to Cross-Species Application

The validation of plant gene function relies heavily on reverse-genetics approaches, with Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) emerging as a particularly powerful tool for transient gene knockdown in species recalcitrant to stable transformation. VIGS operates by harnessing the plant's endogenous post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS) machinery, using recombinant viral vectors to systemically suppress target gene expression. The efficacy of this technology is not merely a function of viral vector selection but is profoundly influenced by the strategic design and orientation of the inserted gene fragment. Within the broader context of plant functional genomics, where techniques range from RNA interference (RNAi) to CRISPR-Cas9-mediated knockout, VIGS offers a unique balance of speed and versatility. This guide objectively compares the performance of different viral vector systems and insert design strategies, providing supporting experimental data to inform researchers' selection and construction protocols for optimal gene functional validation.

Viral Vector Systems for VIGS: A Comparative Analysis

The choice of viral vector is a primary determinant of VIGS success, influencing host range, tissue tropism, and silencing efficiency. Different viral backbones offer distinct advantages and limitations.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Viral Vectors Used in VIGS

| Vector System | Genome Type | Key Features/Advantages | Limitations | Demonstrated Silencing Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco Rattle Virus (TRV) [3] | RNA virus | Broad host range (especially Solanaceae); efficient systemic movement including meristems; mild symptoms. | Bipartite genome requires two vectors (TRV1, TRV2). | ~16.4% in Atriplex canescens (germinated seeds/vacuum infiltration) [35]; 40-80% transcript reduction in N. benthamiana roots with TRV-2b vector [7]. |

| Potato Virus X (PVX) [36] | RNA virus | Well-characterized genome; suitable for deconstruction. | Can cause severe viral symptoms; limited insert capacity (~2 kb). | GFP yield of 0.13 mg/g FW in N. benthamiana; 3-4 fold increase to 0.50 mg/g FW with integrated VSRs [36]. |

| Bean Yellow Dwarf Virus (BeYDV) [37] | DNA virus (Geminivirus) | High-level, transient gene expression; replication in plant nuclei. | Protein detection possible within 3-7 days post-infiltration [37]. | |

| Broad Bean Wilt Virus 2 (BBWV2) [3] | RNA virus | Effective in a range of crops, including pepper. | Widely used for functional genomics in Capsicum annuum [3]. |

The TRV-based system is often the vector of choice for Solanaceae plants like pepper and tomato due to its high efficiency and minimal pathology [3]. A key advancement in TRV vector design involves the retention of the RNA2-encoded 2b protein. Contrary to earlier constructs that deleted this gene, TRV vectors retaining the 2b protein demonstrate significantly enhanced invasion of root and meristematic tissues in Nicotiana benthamiana, Arabidopsis thaliana, and tomato, leading to a more robust and pervasive systemic VIGS response in these critical tissues [7]. This makes the TRV-2b vector indispensable for functional studies of genes involved in root development and soil-borne pathogen interactions.

The Role of Viral Suppressors of RNA Silencing (VSRs)

A significant limitation of viral vectors is their recognition and suppression by the host's RNA silencing machinery. Engineering vectors to co-express heterologous Viral Suppressors of RNA Silencing (VSRs) can dramatically enhance recombinant protein expression and, by extension, silencing potential.

Table 2: Enhancement of VIGS Efficiency via Heterologous VSRs

| VSR | Origin | Mechanism of Action | Experimental Vector | Performance Enhancement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P19 [36] | Tomato bushy stunt virus (TBSV) | Sequesters siRNAs to prevent RISC incorporation. | PVX-derived (pP2) | Markedly enhanced GFP fluorescence and accumulation in N. benthamiana [36]. |

| P38 [36] | Turnip crinkle virus (TCV) | Binds directly to AGO1 protein. | PVX-derived (pP2) | Strong enhancement of GFP expression, second only to NSs [36]. |

| NSs [36] | Tomato zonate spot virus (TZSV) | Targets SGS3 for degradation. | PVX-derived (pP2) | Highest GFP accumulation: 0.50 mg/g FW, a 3.8-fold increase over parental PVX vector [36]. |

A critical finding in vector construction is that the transcriptional orientation of the inserted VSR cassette relative to the target gene is a major factor in its efficacy. Initial constructs with VSR and target gene in the same orientation showed reduced expression, likely due to transcriptional interference. Simply reversing the orientation of the VSR cassette in the PVX-based vector (creating pP3-based constructs) alleviated this interference, leading to a significant boost in the expression of both the VSR and the target gene (e.g., GFP or vaccine antigens VP1 and S2) [36]. For vaccine antigens, this strategy resulted in yield increases of over 100-fold compared to the parental PVX vector [36].

Insert Design: Principles and Protocols

The design of the insert fragment cloned into the viral vector is equally critical for successful silencing.

- Fragment Selection and Size: The insert should be a highly specific, 300-400 base pair fragment derived from the coding sequence of the target gene [3] [35]. Online tools like the SGN-VIGS tool (https://vigs.solgenomics.net/) can be used to predict optimal nucleotide target regions and verify sequence specificity to avoid off-target silencing [35]. Fragments corresponding to the 5' end, central region, and 3' end of the open reading frame are typically tested, with the central fragment often yielding the highest efficiency [35].

- Avoiding Secondary Structure: The insert sequence should be analyzed to avoid regions with high potential for stable secondary structure, which can impede viral replication or the generation of siRNAs.

Experimental Protocol: Cloning and Vector Construction

- Gene Fragment Amplification: Amplify the selected target gene fragment (e.g., AcPDS, AcTIP2;1) from cDNA using primers containing appropriate restriction enzyme sites (e.g., EcoRI and BamHI) [35].

- Restriction Digestion and Ligation: Digest both the amplified PCR product and the VIGS vector (e.g., pTRV2) with the chosen restriction enzymes. Purify the digested fragments and ligate them together using T4 DNA ligase [35].

- Transformation and Verification: Transform the ligation product into competent E. coli cells. Select positive colonies, isolate plasmid DNA, and verify the correct insertion of the gene fragment via colony PCR and sequencing [35].

- Agrobacterium Transformation: Introduce the verified recombinant vector plasmid (e.g., TRV2:Target) and the complementary helper vector (e.g., TRV1) into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 using freeze-thaw transformation [35].

Diagram 1: VIGS Vector Construction Workflow. This diagram outlines the key steps in cloning a target gene fragment into a viral vector for VIGS.

Inoculation Methodologies and Optimization

The method of delivering the viral vector into the plant is a major experimental variable.

Table 3: Comparison of VIGS Inoculation Methods

| Method | Protocol Description | Key Parameters | Optimal Efficiency & Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vacuum Infiltration [35] | Submerging germinated seeds/seedlings in Agrobacterium suspension and applying a vacuum. | 0.5 kPa for 5-10 min; OD600 = 0.8 [35]. | Highest efficiency: 16.4% in A. canescens; ideal for high-throughput silencing of germinated seeds [35]. |

| Syringe Infiltration [37] | Pressing Agrobacterium suspension into the abaxial side of leaves using a needleless syringe. | OD600 = 0.5-1.0; incubation in infiltration buffer (10 mM MES, 200 µM AS, 10 mM MgCl2) [3]. | Standard for leaf assays in model plants like N. benthamiana; suitable for protein expression within days [37]. |

| Soaking [35] | Immersing plant materials in Agrobacterium suspension with gentle shaking. | 40 min immersion; 50 rpm shaking [35]. | Lower efficiency compared to vacuum infiltration; a simpler, less equipment-intensive alternative [35]. |

The plant's developmental stage is also critical. Inoculation of germinated Atriplex canescens seeds with radicles of 1-3 cm resulted in successful systemic silencing, whereas inoculation of intact seeds with seed coats was ineffective [35]. Furthermore, environmental conditions post-inoculation, including temperature, humidity, and photoperiod, must be carefully controlled to optimize both plant health and viral spread, thereby maximizing silencing efficiency [3].

VIGS in the Context of Alternative Gene Silencing Technologies

While VIGS is a powerful knockdown tool, its position within the functional genomics toolkit is defined by comparison with other technologies.

- VIGS vs. RNAi: Both VIGS and transgenic RNAi cause gene knockdown at the mRNA level. However, VIGS is transient and does not require stable transformation, making it faster and applicable to non-transformable species [3]. A significant drawback of RNAi is its propensity for high off-target effects due to the silencing of mRNAs with limited complementarity [38].

- VIGS vs. CRISPR-Cas9: CRISPR-Cas9 creates permanent knockouts at the DNA level, allowing for complete and heritable gene disruption [38]. This is a key advantage for studying essential genes where partial knockdown may not reveal a phenotype. However, lethal knockouts can prevent functional analysis, whereas the transient, partial knockdown of VIGS can still provide insights [38]. CRISPR workflows are also generally longer and more dependent on efficient transformation protocols. Newer CRISPR applications like CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) can create reversible knockouts, blurring the line between the two approaches [38].

Diagram 2: Gene Silencing Technology Comparison. This chart compares the mechanism, effect, and key advantage of VIGS, RNAi, and CRISPR-Cas9.

Case Study: Validating a Root Development Gene

To illustrate the integrated application of these principles, consider a study aiming to validate the function of a putative aquaporin gene (AcPIP2;5) in the root system of Atriplex canescens [35].

- Vector Selection: A TRV-based vector is chosen for its documented efficiency in roots, especially the TRV-2b variant.

- Insert Design: A 428-bp specific fragment from the AcPIP2;5 ORF is selected using the SGN-VIGS tool and cloned into the pTRV2 vector to create TRV2:AcPIP2;5.

- Inoculation: Germinated A. canescens seeds are inoculated with the Agrobacterium suspension (OD600 = 0.8) carrying TRV1 and TRV2:AcPIP2;5 using vacuum infiltration (0.5 kPa, 10 min).

- Validation: Systemic silencing phenotypes appear in new leaves and roots around 15 days post-inoculation. qRT-PCR analysis confirms a 69.5% reduction in AcPIP2;5 transcript abundance, and the observed phenotype (e.g., altered root hydraulics) phenocopies the expected function, validating the gene's role [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagent Solutions for VIGS Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function in VIGS Protocol | Example & Specification |

|---|---|---|

| VIGS Vectors | Engineered viral genomes to deliver and amplify the target gene insert. | pTRV1 and pTRV2 plasmids for TRV-based system [3] [35]. |

| Agrobacterium Strain | Bacterial vehicle for delivering the VIGS vector into plant cells. | A. tumefaciens GV3101 [35]. |

| Infiltration Buffer | Solution to prepare Agrobacterium for plant infiltration. | 10 mM MES, 200 µM Acetosyringone, 10 mM MgCl₂, 0.03% Silwet-77 [35]. |

| Marker Gene | Visual reporter for optimizing silencing efficiency and tracking viral spread. | Phytoene desaturase (PDS); silencing causes photobleaching [3] [35]. |

| Viral Suppressor of RNAi (VSR) | Enhances silencing efficiency by suppressing host defense. | NSs protein from Tomato zonate spot virus for maximum protein yield boost [36]. |

The selection and construction of vectors for VIGS are far from trivial steps, with decisions regarding viral backbone, insert design, orientation, and delivery method directly dictating the success of functional gene validation studies. As the data demonstrates, optimized TRV vectors, particularly those incorporating the 2b protein or heterologous VSRs like NSs in a reverse orientation, can push silencing efficiency to new heights, especially in challenging tissues like roots. When objectively compared to stable RNAi or CRISPR-based knockout, VIGS maintains its niche as the fastest and most accessible technique for transient gene knockdown in non-model plants. The continued refinement of vector design and inoculation protocols ensures that VIGS will remain an indispensable component of the plant functional genomics toolkit, crucial for accelerating gene discovery and crop breeding programs.

In the field of plant functional genomics, Agroinfiltration serves as a cornerstone technique for the transient introduction of genetic material into plant tissues, enabling rapid validation of gene function through approaches such as virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) and knockout studies [3] [39]. This technique leverages the natural DNA transfer capability of Agrobacterium tumefaciens to deliver gene constructs directly into plant cells, bypassing the need for stable transformation [40]. Among the various delivery methods available, vacuum infiltration and seed soaking have emerged as two prominent, efficient protocols, each with distinct advantages and optimal applications for different plant species and experimental requirements. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methodologies, supported by experimental data, to assist researchers in selecting the most appropriate protocol for their functional genomics research.

Seed Soaking Method

The seed soaking method involves immersing germinated or non-germinated seeds in an Agrobacterium suspension for a predetermined duration to facilitate gene transfer. This approach is particularly valued for its technical simplicity and ability to generate whole-plant transformation systems.

- Typical Protocol: In a study on Paeonia ostii, researchers optimized a seed soaking protocol using in vitro embryo-derived seedlings. The optimal conditions identified were an Agrobacterium concentration (OD600) of 1.0, an immersion time of 2 hours, and the inclusion of 200 µM acetosyringone in the infiltration solution [41].

- Plant Material Preparation: The process often begins with sterile embryo excision. For tree peony, this involved inoculating embryos onto specific germination media (MS or WPM) and culturing them under controlled conditions (16h light/8h dark at 24±2°C) to produce consistent seedling materials [41].

Vacuum Infiltration Method

Vacuum infiltration employs negative pressure to remove air from plant tissues, allowing the Agrobacterium suspension to penetrate intercellular spaces more effectively than passive methods.