Validating Deep Learning for Plant Disease Detection: From Laboratory Benchmarks to Real-World Field Deployment

The accurate validation of deep learning algorithms is paramount for transitioning plant disease detection from a research concept to a reliable tool in precision agriculture.

Validating Deep Learning for Plant Disease Detection: From Laboratory Benchmarks to Real-World Field Deployment

Abstract

The accurate validation of deep learning algorithms is paramount for transitioning plant disease detection from a research concept to a reliable tool in precision agriculture. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and scientists engaged in developing and evaluating these diagnostic systems. We explore the foundational challenges, including environmental variability and dataset limitations, that impact model generalizability. The review systematically analyzes state-of-the-art convolutional and transformer-based architectures, highlighting their performance in controlled versus field conditions. Furthermore, we detail optimization strategies—such as lightweight model design and Explainable AI (XAI)—that are critical for robust, transparent, and deployable systems. Finally, we present a comparative analysis of validation metrics and benchmarking standards, offering evidence-based guidelines to bridge the significant performance gap between laboratory results and practical agricultural application.

The Critical Need and Core Challenges in Automated Plant Disease Detection

Plant diseases represent a pervasive and costly threat to global agriculture, directly impacting food security, farmer livelihoods, and economic stability. Quantifying these losses is fundamental for prioritizing research directions, shaping policy interventions, and validating the economic necessity of new technologies, including advanced plant disease detection algorithms. For researchers and scientists developing deep learning-based detection systems, understanding the scale and distribution of economic losses provides a crucial real-world benchmark against which the performance and potential return on investment of new models must be evaluated. This guide synthesizes current, quantified economic impact data from major crop diseases and establishes the experimental protocols used to generate such data, thereby creating a foundation for the empirical validation of disease detection technologies within a broader agricultural context.

Quantified Economic Losses from Major Plant Diseases

The economic burden of plant diseases is immense, with annual global agricultural losses estimated at approximately $220 billion [1]. These losses are not uniformly distributed, affecting specific crops and regions with varying severity. The following tables summarize the quantified economic impacts of key plant diseases, providing a concrete basis for understanding their relative importance.

Table 1: Global and Regional Economic Impact of Major Crop Diseases

| Crop | Disease | Economic Impact | Geographic Scope | Timeframe | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Crops | Various Pathogens | $220 billion (annual losses) | Global | Annual | [1] |

| Wheat | Multiple Diseases | $2.9 billion (560 million bushels lost) | 29 U.S. states & Ontario, Canada | 2018-2021 | [2] |

| Potato | Late Blight | $3-10 billion (annual losses) | Global | Annual | [3] [1] |

| Potato | Late Blight | $6.7 billion (annual losses) | Global | Annual | [4] |

| Olive | Xylella fastidiosa | $1 billion in damage | European olive production | Recent Outbreaks | [1] |

Table 2: Yield Losses and Management Costs of Specific Diseases

| Crop | Disease | Yield Loss | Management Cost / Context | Location / Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat | Fusarium Head Blight, Stripe Rust, Leaf Rust | 1%-20% yield loss forecast (2025) | Fungicide application not recommended for winter wheat | Eastern Pacific Northwest, 2025 Forecast [5] |

| Corn | Southern Rust | 20-40% yield loss in severe cases | Fungicide cost ~$40/acre; effective but costly | Iowa, 2025 Outbreak [6] |

| Potato | Late Blight | 15-30% annual crop loss worldwide | 20-30 fungicide sprays annually in tropical regions | Global [4] |

| Potato | Late Blight | 50-100% yield loss | Fungicides represent 10-25% of harvest value | Central Andes [3] |

Experimental Protocols for Quantifying Disease Incidence and Loss

To generate the economic data presented above, researchers employ standardized experimental protocols. These methodologies are essential for producing reliable, comparable data on disease incidence, severity, and subsequent yield loss. The following workflow visualizes the multi-stage process of a typical yield loss assessment study, as used in the foundational wheat disease loss study [2].

Diagram 1: Yield loss assessment workflow.

Detailed Methodologies for Loss Assessment

The workflow outlined above consists of several critical, procedural stages:

Study Design and Expert Survey Deployment: The wheat disease loss study serves as a prime example of a large-scale, collaborative methodology [2]. Estimates are based on annual surveys completed by Extension specialists and plant pathologists working directly with wheat growers across major production regions. This approach leverages field-level expertise to assess yield losses tied to nearly 30 distinct diseases, providing a rare, ground-truthed perspective.

In-Season Disease Assessment and Yield Monitoring: This stage involves direct field scouting and quantification. For a disease like southern rust in corn, plant pathologists confirm disease presence across geographic areas (e.g., all 99 Iowa counties) and assess severity by evaluating the percentage of leaf area affected [6]. Yield loss is then determined by comparing production from affected fields to expected baseline yields or using paired treated/untreated plots. For instance, fungicide application creates a de facto experimental control; yield differences between treated and untreated areas directly quantify loss [6].

Data Analysis, Economic Valuation, and Modeling: Collected data on yield loss and disease incidence are integrated with economic parameters. This involves applying regional commodity market prices to the volume of lost production to calculate total financial loss, as seen in the wheat study which converted 560 million lost bushels into a $2.9 billion value [2]. For forecasting, models like those used for wheat stripe rust incorporate weather data (e.g., November-February temperatures) to predict potential yield loss ranges for the upcoming season, enabling proactive management [5].

For scientists developing and validating plant disease detection algorithms, access to standardized datasets, reagents, and computational models is essential. The following table details key research reagents and resources that form the foundation of experimental work in this field.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Disease Detection Research

| Resource Category | Specific Example | Function and Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Public Image Datasets | Plant Village [7] | Contains 54,036 images of 14 plants and 26 diseases. Serves as a primary benchmark dataset for training and validating deep learning models for image-based disease classification. |

| Public Image Datasets | PlantDoc [7] | A dataset with images captured in complex natural conditions, used to test model robustness and generalizability beyond controlled lab environments. |

| Public Image Datasets | Plant Pathology 2020-FGVC7 [7] | Provides high-quality annotated apple images, facilitating research on specific disease complexes and multi-class detection. |

| Computational Models | SWIN Transformer [1] | A state-of-the-art deep learning architecture demonstrating 88% accuracy on real-world datasets; used as a performance benchmark. |

| Computational Models | Traditional CNNs (e.g., ResNet) [1] | Classical convolutional neural networks providing baseline performance (e.g., 53% accuracy in real-world settings) for comparative analysis. |

| Experimental Models | SIMPLE-G Model [8] | A gridded economic model used to assess the historical impact of agricultural technologies on land use, carbon stock, and biodiversity, linking disease control to broader environmental outcomes. |

| Biological Materials | CIP-Asiryq Potato [3] | A late blight-resistant potato variety developed using wild relatives. Serves as a critical experimental control in field trials to quantify losses in susceptible varieties. |

Performance Benchmarking of Detection Modalities and Models

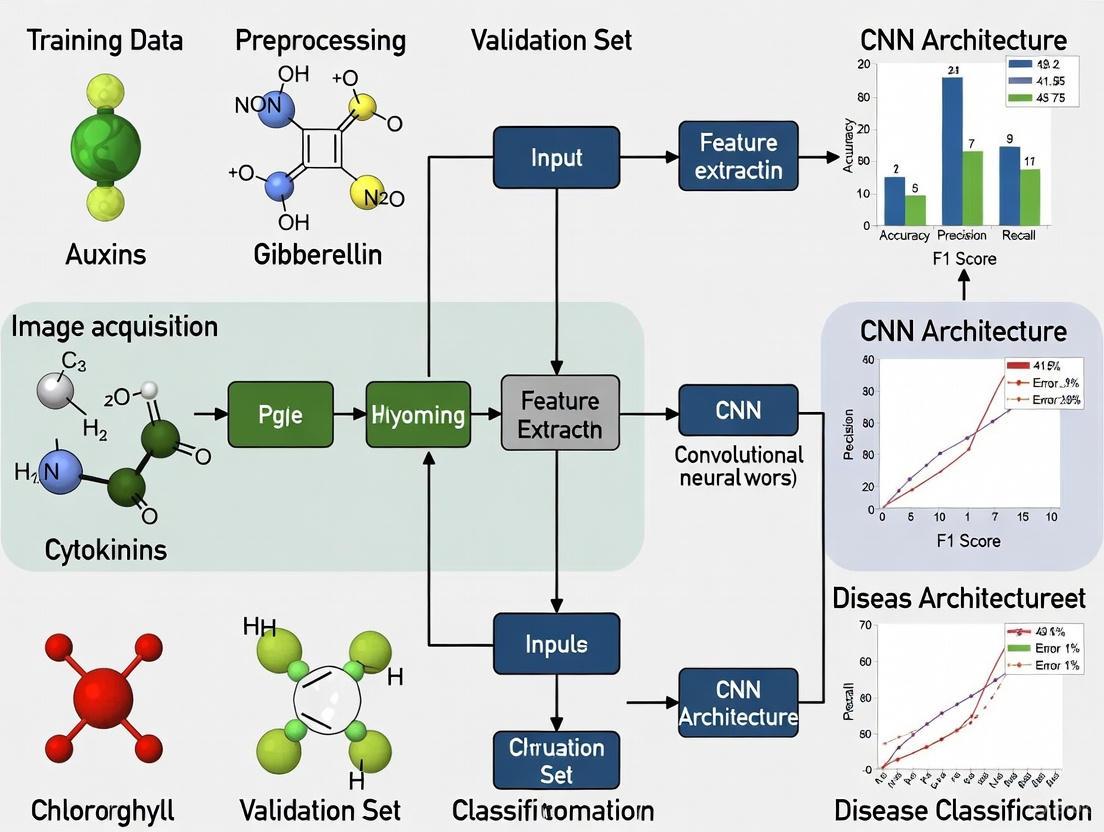

A critical step in validating deep learning algorithms is benchmarking their performance against established modalities and architectures. This comparison must extend beyond simple accuracy to include robustness in real-world conditions. The following diagram illustrates the performance landscape of major model types and imaging modalities, highlighting the core trade-offs.

Diagram 2: Detection model and modality comparison.

The performance gap between laboratory and field conditions is a central challenge. While deep learning models can achieve 95-99% accuracy in controlled lab settings, their performance can drop to 70-85% when deployed in real-world field conditions [1]. This highlights the critical need for robust validation against diverse, field-level data. Transformer-based architectures like the SWIN Transformer have demonstrated superior robustness, achieving 88% accuracy on real-world datasets, a significant improvement over the 53% accuracy observed for traditional CNNs under the same conditions [1]. This performance gap directly impacts economic outcomes; earlier and more accurate detection enabled by robust models can inform timely interventions, reducing the need for costly blanket fungicide applications and mitigating yield loss [9] [6].

The quantified economic losses from plant diseases—ranging from billions of dollars in specific crops to a global total of $220 billion annually—provide an unambiguous rationale for the development of advanced detection technologies. The experimental protocols for loss assessment and the evolving performance benchmarks for deep learning models create a essential framework for researchers. Validating new algorithms against these real-world economic and agronomic metrics is not merely an academic exercise; it is a necessary step to ensure that technological advancements in plant disease detection translate into tangible, field-ready solutions that can mitigate these significant economic losses and enhance global food security.

Plant diseases pose a significant threat to global food security, causing an estimated $220 billion in annual agricultural losses worldwide and destroying up to 14.1% of total crop production [10] [1]. Traditional visual inspection methods, reliant on human expertise, have proven inadequate—they are labor-intensive, time-consuming, and prone to error, often resulting in ineffective treatment and excessive pesticide use [11] [7] [12]. The exponential growth in global population, projected to reach 9.8 billion by 2050, necessitates a 70% increase in food production, creating an urgent need for technological solutions that can enhance agricultural productivity, resilience, and sustainability [10] [13].

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI), particularly deep learning, has revolutionized plant disease diagnostics by enabling rapid, non-invasive, and large-scale detection directly from leaf images [13]. This evolution from manual inspection to automated, data-driven systems represents a paradigm shift in agricultural management, offering the potential for early intervention, reduced crop losses, and improved yield quality. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of modern deep learning approaches for plant disease detection, evaluating their performance, experimental protocols, and practical applicability for research and development.

The Evolution of Diagnostic Methods in Agriculture

The journey from traditional to AI-powered disease diagnosis in agriculture reflects broader technological advancements. Initial reliance on human expertise has progressively incorporated computational methods, each stage building upon the last to increase accuracy, speed, and scalability.

From Traditional Methods to Digital Solutions

Traditional visual inspection by farmers and agricultural experts formed the foundation of plant disease diagnosis for centuries. This approach depended on recognizing visual symptoms such as color changes, lesions, spots, or abnormal growth patterns. However, this method suffered from significant limitations: it required substantial expertise, was impractical for large-scale farming operations, and often failed to detect diseases at early stages when intervention is most effective [7] [12]. The subjective nature of human assessment also led to inconsistent diagnoses, resulting in either insufficient or excessive pesticide application, with negative economic and environmental consequences [12].

The advent of digital imaging and classical image processing techniques marked the first technological transition. Researchers began applying color-based segmentation, texture analysis, and shape detection algorithms to identify diseased regions in plant images. These methods typically involved multiple stages: image acquisition, preprocessing (noise removal, contrast enhancement), segmentation (separating diseased tissue from healthy tissue and background), feature extraction (identifying characteristic patterns), and classification using machine learning algorithms [12]. While this represented a significant advancement, these approaches remained limited by their reliance on handcrafted features, which often failed to capture the complex visual patterns associated with different diseases, especially under varying field conditions [13] [1].

The Machine Learning Transition

Classical machine learning algorithms, including Support Vector Machines (SVM), k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN), Decision Trees, and Random Forests, brought more sophistication to plant disease diagnosis. These algorithms could learn patterns from extracted features and make predictions on new images. Studies utilizing these approaches focused on optimizing feature selection, often combining color, texture, and shape descriptors to improve classification accuracy [12].

However, these traditional machine learning methods faced fundamental challenges. Their performance heavily depended on domain expertise for manual feature engineering, which was both time-consuming and inherently limited in capturing the full complexity of plant diseases. Furthermore, these models typically struggled with real-world variability in lighting conditions, leaf orientations, backgrounds, and disease manifestations across different growth stages [12]. The feature extraction process often failed to generalize across diverse agricultural environments, limiting practical deployment and scalability for widespread agricultural use.

The Deep Learning Revolution

The emergence of deep learning, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), represents the most significant advancement in plant disease diagnostics. Unlike traditional methods, CNNs automatically learn hierarchical feature representations directly from raw pixel data, eliminating the need for manual feature engineering [13] [7]. This capability allows them to capture intricate patterns and subtle distinctions between disease symptoms that are often imperceptible to human experts or traditional algorithms.

The adoption of transfer learning has further accelerated this revolution. Researchers routinely utilize pre-trained architectures (VGG, ResNet, Inception, MobileNet) developed on large-scale datasets like ImageNet, fine-tuning them for specific plant disease classification tasks [10] [11] [14]. This approach leverages generalized visual features learned from diverse images, significantly reducing computational requirements and training time while improving performance, especially with limited labeled agricultural data [11] [12]. The integration of Explainable AI (XAI) techniques such as Grad-CAM and Grad-CAM++ has enhanced model transparency by providing visual explanations of predictions, highlighting the specific leaf regions influencing classification decisions and building trust among end-users [10] [11].

Comparative Analysis of Modern Deep Learning Architectures

Modern plant disease detection systems employ diverse neural architectures, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and performance characteristics. The selection of an appropriate architecture involves balancing multiple factors including accuracy, computational efficiency, and practical deployability.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Deep Learning Models on Benchmark Datasets

| Model Architecture | Reported Accuracy (%) | Dataset | Key Strengths | Computational Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WY-CN-NASNetLarge [10] | 97.33% | Integrated Wheat & Corn | Multi-scale feature extraction, severity assessment | High parameter count, suitable for server-side deployment |

| Mob-Res (MobileNetV2 + Residual) [11] | 99.47% | PlantVillage | Lightweight (3.51M parameters), mobile deployment | Optimized for resource-constrained devices |

| Custom CNN [14] | 95.62% - 100%* | Combined Plant Dataset | Adaptable architecture, high performance on specific plants | Architecture varies by application |

| SWIN Transformer [1] | 88.00% | Real-World Field Conditions | Superior robustness to environmental variability | Moderate to high computational requirements |

| Traditional CNNs [1] | 53.00% | Real-World Field Conditions | Established architecture, extensive documentation | Poor generalization to field conditions |

| Vision Transformer (ViT) [11] | Varied (Competitive) | Multiple Benchmarks | State-of-the-art on some tasks | High computational demand, data hungry |

Note: Accuracy range represents performance across different plant types including 100% for potato, pepper bell, apple, and peach; 98% for tomato and rice; and 99% for grape [14].

Convolutional Neural Network Architectures

CNNs remain the foundational architecture for plant disease detection, with numerous variants demonstrating exceptional performance on standardized datasets. The WY-CN-NASNetLarge model exemplifies advanced CNN applications, specifically designed for large-scale plant disease detection with emphasis on severity assessment. This model utilizes the NASNetLarge architecture with pre-trained ImageNet weights, employing transfer learning, fine-tuning, and comprehensive data augmentation techniques to achieve 97.33% accuracy on an integrated dataset of wheat yellow rust and corn northern leaf spot, predicting across 12 severity classes [10]. Its sophisticated approach incorporates the AdamW optimizer, dropout training, and mixed precision training, demonstrating how advanced optimization techniques can enhance performance while preventing overfitting.

Lightweight CNN architectures have emerged as particularly valuable for practical agricultural applications. The Mob-Res model exemplifies this category, combining MobileNetV2 with residual blocks to create a highly efficient architecture with only 3.51 million parameters while maintaining exceptional accuracy (99.47% on PlantVillage dataset) [11]. This design philosophy prioritizes deployment feasibility on mobile and edge devices with limited computational resources, addressing a critical constraint in real-world agricultural environments where cloud connectivity may be unreliable or unavailable [11] [1]. Studies implementing multiple CNN architectures across various plant types have demonstrated remarkable performance variations, with certain models achieving perfect classification for specific crops like potato, pepper bell, apple, and peach, while others show slightly reduced but still impressive performance for more challenging classifications [14].

Emerging Architectures: Transformers and Hybrid Models

Vision Transformers (ViTs) represent a architectural shift away from convolutional inductive biases toward self-attention mechanisms, demonstrating competitive performance in plant disease classification. The SWIN Transformer architecture has shown particular promise in agricultural applications, achieving 88% accuracy on real-world datasets compared to just 53% for traditional CNNs, highlighting its superior robustness to environmental variability [1]. This performance advantage stems from the self-attention mechanism's ability to capture global contextual relationships within images, potentially making them more resilient to the occlusions, lighting variations, and complex backgrounds characteristic of field conditions.

Hybrid models that combine convolutional layers with transformer components have emerged to leverage the strengths of both architectural paradigms. These models typically use CNNs for local feature extraction and transformers for capturing long-range dependencies, creating synergistic architectures that outperform either approach alone [12]. Recent research has also explored the integration of Convolutional Swin Transformers (CST), which blend convolutional layers with transformer-based techniques for enhanced feature extraction [11]. As model architectures continue to evolve, the agricultural AI research community is increasingly focusing on practical deployment considerations rather than purely theoretical advancements, with emphasis on robustness, efficiency, and interpretability.

Experimental Protocols and Validation Frameworks

Robust experimental design and rigorous validation are essential for developing reliable plant disease detection systems. Standardized protocols enable meaningful comparisons across studies and ensure reproducible results.

Dataset Curation and Preprocessing

The foundation of any effective plant disease detection system is a comprehensive, well-annotated dataset. Several benchmark datasets have emerged as standards for training and evaluation:

- PlantVillage: Contains 54,036 images spanning 14 plant species and 26 diseases (38 total classes), though predominantly captured under controlled laboratory conditions with simple backgrounds [11] [7].

- Plant Disease Expert: A larger dataset with 199,644 images across 58 classes, providing greater diversity for training robust models [11].

- PlantDoc: Designed specifically for real-world conditions, containing images with complex backgrounds and environmental variations [7].

- Specialized Datasets: Focused collections like the Corn Disease and Severity (CD&S) and Yellow-Rust-19 datasets provide targeted imagery for specific disease severity assessment [10].

Data augmentation techniques are universally employed to enhance dataset diversity and improve model generalization. Standard practices include rotation, zooming, shifting, flipping, and color variation, effectively creating synthetic training examples that increase robustness to the variations encountered in real agricultural environments [10] [11]. For datasets with class imbalances—a common challenge when certain diseases occur more frequently than others—techniques such as weighted loss functions, oversampling of minority classes, and specialized sampling methods help prevent model bias toward frequently occurring conditions [1] [12].

Model Training Methodologies

Modern plant disease detection systems employ sophisticated training strategies to optimize performance:

Transfer Learning: Nearly all contemporary approaches utilize pre-trained models (VGG, ResNet, MobileNet, NASNet) initially trained on ImageNet, leveraging generalized visual feature extraction capabilities before fine-tuning on plant-specific datasets [10] [11] [14]. This approach significantly reduces training time and computational requirements while improving performance, especially with limited labeled agricultural data.

Advanced Optimizers: The AdamW optimizer has demonstrated superior performance for plant disease classification, effectively managing weight decay and improving generalization compared to traditional optimizers [10]. This is particularly valuable for overcoming overfitting when working with limited training data.

Progressive Training Strategies: Mixed precision training, which utilizes both 16-bit and 32-bit floating-point numbers, accelerates computation while maintaining stability, enabling faster iteration and larger model deployment on hardware with memory constraints [10].

Regularization Techniques: Dropout, batch normalization, and early stopping are routinely employed to prevent overfitting, especially important given the relatively limited size of most plant disease datasets compared to general computer vision benchmarks [10] [11].

Table 2: Standard Experimental Protocol for Plant Disease Detection Models

| Experimental Phase | Key Components | Purpose | Common Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Preparation | Dataset collection, Train-validation-test split (70-15-15), Data augmentation | Ensure representative sampling, prevent data leakage | Multiple public datasets (PlantVillage, PlantDoc), Rotation/flipping/zooming augmentation |

| Model Setup | Backbone selection, Transfer learning, Optimizer configuration | Leverage pre-trained features, efficient convergence | ImageNet pre-trained weights, Adam/AdamW optimizer, learning rate scheduling |

| Training | Loss function, Regularization, Callbacks | Optimize parameters, prevent overfitting | Categorical cross-entropy, Dropout, Early stopping, ReduceLROnPlateau |

| Evaluation | Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score, Confusion matrix | Comprehensive performance assessment | Cross-validation, Class-wise metrics, Hamming score (multilabel) |

| Interpretability | Grad-CAM, Grad-CAM++, LIME | Visual explanation, Build trust, Debug predictions | Heatmap visualization of decisive regions |

Performance Validation Metrics

While accuracy remains a commonly reported metric, comprehensive model evaluation requires multiple complementary measures to provide a complete performance picture, especially given the frequent class imbalances in plant disease datasets [15] [12]:

- Precision: Measures the proportion of correctly identified positive predictions among all positive predictions, crucial when false positives are costly (e.g., unnecessary pesticide application) [12].

- Recall: Measures the proportion of actual positives correctly identified, essential when missing true positives is costly (e.g., failing to detect a devastating disease) [12].

- F1-Score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a balanced metric particularly valuable for imbalanced datasets [12].

- Confusion Matrix: A detailed visualization of model predictions versus actual labels, revealing specific patterns of misclassification across disease categories [15].

- Hierarchical Metrics: For severity assessment, specialized metrics that account for ordinal relationships between severity levels provide more nuanced evaluation than standard classification metrics [10].

The "accuracy paradox" presents a particular challenge in plant disease detection—models can achieve high overall accuracy by simply predicting the majority class while performing poorly on rare but potentially devastating diseases [15]. This underscores the necessity of comprehensive multi-metric evaluation beyond simple accuracy reporting.

Performance Benchmarking Across Environments

A critical consideration in plant disease detection is the significant performance gap between controlled laboratory conditions and real-world agricultural environments.

Laboratory vs. Field Performance

Deep learning models consistently achieve impressive results on curated laboratory datasets, with numerous studies reporting accuracy exceeding 95-99% on datasets like PlantVillage [11] [14] [1]. However, these results often fail to translate directly to field conditions, where performance typically drops to 70-85% for most traditional CNN architectures [1]. This performance discrepancy stems from numerous environmental challenges including varying lighting conditions, complex backgrounds, leaf occlusions, different growth stages, and multiple disease co-occurrences that are underrepresented in standardized datasets [1].

Transformers and hybrid architectures demonstrate superior robustness to these environmental variations, with SWIN Transformers maintaining 88% accuracy on real-world datasets compared to just 53% for traditional CNNs [1]. This substantial performance advantage (35% higher accuracy) highlights the importance of architectural selection for practical deployment scenarios. The self-attention mechanisms in transformer-based models appear better equipped to handle the complex visual relationships present in field conditions where diseases manifest differently than in controlled laboratory settings.

Cross-Domain Generalization

The ability of models to generalize across geographic locations, plant cultivars, and environmental conditions remains a significant challenge. Most models experience performance degradation when applied to new environments not represented in their training data [1]. Techniques such as cross-domain validation rates (CDVR) have been developed to quantitatively assess this generalization capability, with models like Mob-Res demonstrating competitive cross-domain adaptability compared to other pre-trained models [11].

Domain adaptation methods, including style transfer and domain adversarial training, show promise for addressing these generalization challenges by explicitly minimizing the discrepancy between source (training) and target (deployment) distributions [1]. Additionally, the creation of more diverse datasets encompassing broader geographic and environmental conditions is essential for developing models that maintain performance across different agricultural regions and farming practices.

Implementing effective plant disease detection systems requires specialized computational resources, datasets, and evaluation tools. This research toolkit provides the foundational components for developing and validating diagnostic algorithms.

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for Plant Disease Detection Systems

| Toolkit Component | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public Datasets | PlantVillage, PlantDoc, Plant Pathology 2020-FGVC7, Cucumber Plant Diseases Dataset | Benchmark training and evaluation, Standardized performance comparison | Laboratory vs. field image balance, Geographic and seasonal representation |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | TensorFlow, PyTorch, Keras | Model architecture implementation, Training pipeline development | GPU acceleration support, Distributed training capabilities |

| Pre-trained Models | ImageNet weights for VGG, ResNet, MobileNet, EfficientNet | Transfer learning initialization, Feature extraction backbone | Model size vs. accuracy trade-offs, Compatibility with deployment targets |

| Data Augmentation Libraries | TensorFlow ImageDataGenerator, Albumentations, Imgaug | Dataset diversification, Improved model generalization | Domain-appropriate transformations, Natural image variation simulation |

| Evaluation Metrics | Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score, Confusion Matrix, ROC-AUC | Comprehensive performance assessment, Model comparison and selection | Class imbalance adjustments, Statistical significance testing |

| Interpretability Tools | Grad-CAM, Grad-CAM++, LIME | Model decision explanation, Feature importance visualization | Technical vs. non-technical audience presentation, Trust building |

| Mobile Deployment Frameworks | TensorFlow Lite, ONNX Runtime, PyTorch Mobile | Edge device optimization, Offline functionality enablement | Model quantization, Hardware-specific acceleration |

Computational Infrastructure and Deployment Considerations

The computational requirements for plant disease detection vary significantly based on model architecture and deployment context. Training complex models like NASNetLarge or Vision Transformers typically demands substantial GPU resources, often requiring multiple high-end graphics cards for days or weeks depending on dataset size [10]. However, optimized inference can be achieved on resource-constrained devices through model quantization, pruning, and knowledge distillation techniques [11].

Successful real-world implementations highlight the importance of deployment planning. The Plantix application, with over 10 million users, demonstrates the feasibility of mobile disease detection, emphasizing offline functionality and multilingual support for broad accessibility [1]. Economic considerations also play a crucial role in technology adoption, with RGB-based systems costing $500-2,000 compared to $20,000-50,000 for hyperspectral imaging systems, creating different adoption barriers and use cases for each technology tier [1].

Future Directions and Research Opportunities

Despite significant advances, plant disease detection using deep learning faces several challenges that represent opportunities for future research and development.

Addressing Technical Limitations

Future research directions focus on overcoming current limitations in robustness, efficiency, and applicability:

Lightweight Model Design: Developing increasingly efficient architectures that maintain high accuracy while reducing computational requirements for deployment in resource-constrained agricultural environments [11] [1] [12].

Cross-Geographic Generalization: Creating models that maintain performance across diverse geographic regions, climate conditions, and agricultural practices through improved domain adaptation techniques and more representative datasets [1].

Multimodal Data Fusion: Integrating RGB imagery with complementary data sources such as hyperspectral imaging, environmental sensors, and meteorological data to improve detection accuracy and enable pre-symptomatic identification [1].

Explainable AI Integration: Enhancing model interpretability through advanced visualization techniques and transparent decision-making processes to build trust among farmers and agricultural professionals [11] [13].

Emerging Technologies and Methodologies

Several emerging technologies show particular promise for advancing plant disease detection:

Vision-Language Models (VLM): Integrating visual recognition with natural language understanding for improved farmer interaction, automated annotation, and knowledge-based diagnostics [13] [1].

Few-Shot and Self-Supervised Learning: Reducing dependency on large annotated datasets by developing techniques that learn effectively from limited labeled examples, addressing a critical bottleneck in model development [1] [12].

Edge AI and IoT Integration: Creating distributed intelligence systems that combine cloud processing with edge computation for real-time monitoring and response in field conditions [13] [12].

Generative AI for Data Augmentation: Using generative adversarial networks (GANs) and diffusion models to create synthetic training data that addresses class imbalances and rare disease scenarios [12].

As these technologies mature, the focus will shift from pure algorithmic performance to integrated systems that address the complete agricultural disease management lifecycle, from early detection through treatment recommendation and impact assessment, ultimately contributing to improved global food security and sustainable agricultural practices.

The integration of deep learning for plant disease detection represents a significant advancement in precision agriculture, offering the potential for rapid, large-scale monitoring to safeguard global food security. However, a substantial and often overlooked challenge is the significant performance drop these models exhibit when moving from controlled laboratory conditions to real-world field environments. This lab-to-field performance gap poses a major obstacle to practical deployment and effectiveness. A critical analysis of experimental data reveals that models achieving exceptional accuracy (95-99%) on curated lab datasets can see their performance plummet to 70-85% when faced with the complex and unpredictable conditions of the field [1]. This article provides a comparative analysis of this performance disparity, details the experimental methodologies that expose it, and underscores why rigorous, multi-stage validation is not just beneficial but essential for developing robust, field-ready plant disease detection systems.

Quantifying the Performance Gap: A Data-Driven Comparison

The chasm between laboratory and field performance is not merely anecdotal; it is consistently demonstrated and quantified across numerous studies and datasets. The following table synthesizes key performance metrics from various research efforts, highlighting this critical discrepancy.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Models in Laboratory vs. Field Conditions

| Model / Architecture | Laboratory Accuracy (%) | Field Accuracy (%) | Performance Gap (Percentage Points) | Dataset(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional CNNs (e.g., AlexNet, VGG) | 95 - 99 [1] [14] | ~53 [1] | ~42 - 46 | PlantVillage [16], PlantDoc [17] [1] |

| Advanced Architectures (SWIN Transformer) | - | ~88 [1] | - | PlantDoc [1] |

| MSUN (Domain Adaptation) | - | 56.06 - 96.78 [17] | - | PlantDoc, Corn-Leaf-Diseases [17] |

| Custom CNN (Real-time System) | 95.62 - 100 [14] | Not Reported | - | Combined Dataset (PlantVillage, etc.) [14] |

| Depthwise CNN with SE & Residual | 98.00 [18] | Not Reported | - | Comprehensive Multi-Species Dataset [18] |

| YOLOv8 (Object Detection) | 91.05 mAP [16] | Not Reported | - | Detecting Diseases Dataset [16] |

The data reveals a stark contrast. While models can be tuned to near-perfection in the lab, their performance on field-based datasets like PlantDoc is significantly lower. This underscores the limitation of laboratory-only validation. The superior performance of the SWIN Transformer on field data suggests that advanced architectures are better at handling real-world complexity [1]. Furthermore, the MSUN framework, which specifically addresses the "domain shift" problem, demonstrates that targeted strategies can significantly improve field performance for specific crops and conditions [17].

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking and Validation

To reliably identify the performance gap, researchers employ standardized experimental protocols centered on dataset selection, model training, and rigorous cross-environment testing.

Dataset Curation and Characteristics

A critical first step is the use of benchmark datasets that include both lab and field imagery.

- Laboratory Datasets: The PlantVillage dataset is a prime example, consisting of over 50,000 lab-quality images of plant leaves against homogeneous, clean backgrounds [16] [14]. This dataset is ideal for initial model training but lacks environmental variability.

- Field Datasets: The PlantDoc dataset was specifically created to provide a more realistic benchmark. It contains images sourced from the internet with complex backgrounds, varied lighting, multiple leaves, and different angles, making it a robust test for field generalizability [17] [1].

- Experimental Protocol: A standard methodology involves training a model on a large lab-style dataset like PlantVillage and then testing its performance on a held-out test set from PlantVillage (lab accuracy) and on the entire PlantDoc dataset (field accuracy) [17] [1]. This direct comparison quantifies the domain shift effect.

Unsupervised Domain Adaptation (UDA)

To bridge the performance gap, advanced techniques like Unsupervised Domain Adaptation (UDA) are employed. The experimental protocol for frameworks like MSUN involves [17]:

- Input: A large set of labeled source domain images (e.g., lab images from PlantVillage) and a large set of unlabeled target domain images (e.g., field images from PlantDoc).

- Feature Alignment: The model is trained to learn domain-invariant features by aligning the feature distributions of the source and target domains. The MSUN framework uses a Multi-Representation Subdomain Adaptation Module to capture both overall structure and fine-grained details, addressing large inter-domain discrepancies and fuzzy class boundaries.

- Uncertainty Regularization: An auxiliary regularization loss is added to suppress prediction uncertainties caused by domain transfer, which is crucial for dealing with the cluttered backgrounds and noise in field images.

- Evaluation: The model is evaluated solely on the labeled test set of the target (field) domain to measure its real-world efficacy, achieving state-of-the-art results on datasets like PlantDoc [17].

Visualizing the Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the critical pathway for developing and validating a robust plant disease detection model, emphasizing the points where the performance gap is measured and addressed.

Validation Workflow for Robust Models

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers embarking on the development and validation of plant disease detection models, a specific set of "reagent solutions" or core components is required. The table below details these essential elements.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Plant Disease Detection Research

| Research Reagent | Function & Role in Validation | Examples & Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Curated Image Datasets | Serves as the fundamental substrate for training and testing models. The choice of dataset directly dictates how performance will be measured. | PlantVillage (Lab-condition) [16], PlantDoc (Field-condition) [17], Corn-Leaf-Diseases [17] |

| Deep Learning Architectures | The core analytical tool that learns to map image features to disease classes. Different architectures have varying capacities for handling domain shift. | Traditional CNNs (ResNet, VGG) [19], Vision Transformers (SWIN, ViT) [1] [9], Lightweight CNNs (MobileNet) for deployment [16] [18] |

| Domain Adaptation Algorithms | Computational reagents designed specifically to minimize the distribution gap between lab and field data, directly addressing the performance gap. | MSUN Framework [17], Subdomain Adaptation Modules [17], Adversarial Training [17] |

| Evaluation Metrics | Quantitative measures that act as assays for model performance. Moving beyond simple accuracy is crucial for meaningful validation. | Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score [9], mean Average Precision (mAP) for object detection [16], Severity Estimation Accuracy [10] |

| Visualization Tools | Tools that provide interpretability, allowing researchers to understand what features the model is using for prediction, building trust in the system. | Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) [10] |

The evidence is clear and compelling: a plant disease detection model's exceptional performance in the laboratory is no guarantee of its utility in the field. The performance gap, often a drop of 20-40 percentage points in accuracy, is a fundamental challenge that must be confronted [1]. Navigating this gap requires a non-negotiable commitment to rigorous, multi-faceted validation using field-realistic benchmarks and the adoption of advanced strategies like domain adaptation and transformer architectures. The path forward for researchers is to prioritize generalization and robustness from the outset, treating field validation not as a final check but as an integral component of the model development lifecycle. By doing so, the promise of deep learning to revolutionize plant disease management and enhance global food security can be fully realized.

The deployment of deep learning models for plant disease detection represents a significant advancement in precision agriculture. However, a critical challenge persists: the performance gap between controlled laboratory conditions and real-world field deployment. Models often achieve 95–99% accuracy in laboratory settings but see their performance drop to 70–85% when confronted with the vast variability of actual agricultural environments [1]. This discrepancy stems from the complex data diversity encountered across plant species, disease symptom manifestations, and environmental conditions. This review systematically compares the performance of contemporary deep learning architectures against these real-world variabilities, providing a validation framework grounded in experimental data to guide researchers and developers in creating more robust and generalizable plant disease detection systems.

Performance Benchmarking Across Species and Environments

The generalization capability of deep learning models is fundamentally tested by biological diversity and environmental variability. Performance metrics reveal significant differences across architectures and deployment contexts.

Table 1: Model Performance Across Laboratory and Field Conditions

| Model Architecture | Reported Laboratory Accuracy (%) | Reported Field Accuracy (%) | Primary Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| SWIN Transformer | 95-99 [1] | 88 [1] | Multi-species, real-world datasets |

| Vision Transformer (ViT) | 98.9 [20] | 85-90 (estimated) | Wheat leaf diseases |

| Modified 7-block ViT | 98.9 [20] | N/R | Wheat leaf diseases |

| ConvNeXt | 95-99 [1] | 70-85 [1] | Multi-species generalization |

| ResNet50 | 99.13 [21] | N/R | Rice leaf diseases |

| Ensemble (ResNet50+MobileNetV2) | 99.91 [22] | N/R | Tomato leaf diseases |

| Traditional CNNs | 95-99 [1] | 53 [1] | Multi-species baseline |

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across Plant Species

| Plant Species | Best Performing Model | Reported Accuracy (%) | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat | Modified 7-block ViT [20] | 98.9 | Rust diseases, septoria |

| Tomato | Ensemble (ResNet50+MobileNetV2) [22] | 99.91 | Multiple disease types, occlusion |

| Rice | ResNet50 [21] | 99.13 | Bacterial blight, brown spot |

| Multiple crops | SWIN Transformer [1] | 88.0 (field) | Cross-species generalization |

Experimental Protocols for Robust Validation

Three-Stage Evaluation Methodology

A comprehensive validation methodology is essential for accurate performance assessment. Recent research proposes a three-stage evaluation framework that extends beyond traditional metrics [21]:

- Traditional Performance Metrics: Initial assessment using standard classification metrics including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score.

- Explainable AI Visualization: Application of techniques like Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME) to visualize features influencing model decisions.

- Quantitative XAI Evaluation: Introduction of novel metrics including Intersection over Union (IoU), Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC), and an overfitting ratio to quantify model reliability and feature selection appropriateness.

This methodology revealed critical insights despite similar traditional performance metrics. For instance, while ResNet50 achieved 99.13% accuracy with strong feature selection (IoU: 0.432), other models like InceptionV3 and EfficientNetB0 showed poorer feature selection capabilities (IoU: 0.295 and 0.326) despite high accuracy, indicating potential reliability issues in real-world applications [21].

Cross-Species Generalization Protocols

Evaluating cross-species generalization involves rigorous experimental designs:

- Dataset Composition: Utilizing diverse datasets such as Plant Village (14 plants, 26 diseases, 54,036 images) and PlantDoc for real-world images [7].

- Transfer Learning Assessment: Measuring performance degradation when models trained on one species (e.g., tomato) are applied to another (e.g., cucumber) without retraining [1].

- Domain Adaptation Techniques: Implementing adversarial training and feature alignment to minimize domain shift between laboratory and field conditions [23].

Figure 1: Comprehensive Workflow for Plant Disease Detection and Validation

Analysis of Architectural Approaches to Data Diversity

Transformer vs. CNN Architectures

Transformer-based architectures demonstrate superior performance in handling diverse data conditions compared to traditional CNNs. The SWIN Transformer achieves 88% accuracy on real-world datasets, significantly outperforming traditional CNNs at 53% under similar conditions [1]. This performance advantage stems from the self-attention mechanism's ability to capture long-range dependencies and global context, which is particularly valuable for recognizing varied disease patterns across different species and environmental conditions.

Vision Transformers modified for agricultural applications have shown remarkable results. A modified 7-block ViT architecture achieved 98.9% accuracy on wheat leaf diseases, leveraging multi-scale feature extraction capabilities to handle symptom variability [20]. The incorporation of skip connections further enhances gradient flow and feature reuse, improving detection of subtle disease patterns.

Hybrid and Ensemble Approaches

Hybrid architectures that combine CNNs with transformers effectively leverage both local and global feature information. The E-TomatoDet model integrates CSWinTransformer for global feature capture with a Comprehensive Multi-Kernel Module (CMKM) for multi-scale local feature extraction, achieving a mean Average Precision (mAP50) of 97.2% on tomato leaf disease detection [24]. This approach addresses the limitation of CNNs in capturing global context and transformers in capturing fine local details.

Ensemble methods combining multiple architectures demonstrate complementary strengths. An ensemble of ResNet50 and MobileNetV2 achieved 99.91% accuracy on tomato leaf disease classification by concatenating feature maps from both models, creating richer feature representations [22]. The ResNet50 component captures hierarchical features while MobileNetV2 provides efficient spatial information, creating a more robust detection system.

Figure 2: Architectural Approaches to Handling Data Diversity in Plant Disease Detection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Plant Disease Detection

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Public Datasets | Plant Village (54,036 images, 14 plants, 26 diseases) [7], Plant Pathology 2020-FGVC7 (3,651 apple images) [7], PlantDoc (real-world images) [7] | Benchmarking model performance, training foundation models, cross-species generalization studies |

| Model Architectures | SWIN Transformer [1], Vision Transformers (ViT) [20], ResNet50 [22] [21], EfficientNet [23], YOLO variants [25] [24] | Backbone networks for feature extraction, object detection frameworks, comparative performance studies |

| Evaluation Frameworks | Three-stage methodology (Traditional metrics + XAI + Quantitative analysis) [21], mAP@0.5 [25], IoU for feature localization [21] | Model validation, reliability assessment, interpretability analysis, performance benchmarking |

| Explainability Tools | LIME [21], Grad-CAM [21], Prototype-based methods (CDPNet) [26] | Model decision interpretation, feature importance visualization, trust-building for adoption |

| Data Augmentation | Multi-level contrast enhancement [20], Rotation/flipping/cropping [25], Synthetic data generation (GANs) [23] | Addressing class imbalance, improving model robustness, expanding training data diversity |

Confronting data diversity in plant disease detection requires a multifaceted approach that addresses variability across species, symptoms, and environments. Transformer-based architectures, particularly SWIN and modified ViTs, demonstrate superior robustness in field conditions compared to traditional CNNs, with hybrid models showing promising results by combining local and global feature extraction capabilities. The significant performance gap between laboratory (95-99% accuracy) and field conditions (70-85% accuracy) highlights the critical need for more realistic validation protocols and diverse training datasets. Future research directions should prioritize the development of lightweight models for resource-constrained environments, improved cross-geographic generalization, and enhanced explainability to foster trust among end-users. By addressing these challenges through architectural innovation and rigorous validation methodologies, the research community can advance plant disease detection from laboratory prototypes to practical agricultural tools that enhance global food security.

The development of robust deep learning models for plant disease detection is critically dependent on the quality and composition of the training data. The "annotation bottleneck" refers to the significant constraints imposed by the need for expertly labeled datasets, a process that is both time-consuming and costly. In plant pathology, this challenge is exacerbated by the necessity for annotations from specialized experts, including plant pathologists, who must verify disease classifications—creating a major bottleneck in dataset expansion and diversification [1]. This expert dependency means that datasets often contain regional biases and coverage gaps for certain species and disease variants, directly impacting model generalization capabilities [1].

Compounding the annotation challenge is the pervasive issue of class imbalance, where natural imbalances in disease occurrence create significant obstacles for developing equitable detection systems. Common diseases typically have abundant examples in datasets, while rare conditions suffer from limited representation [1]. This imbalance often biases models toward frequently occurring diseases at the expense of accurately identifying rare but potentially devastating conditions [27]. When a dataset is highly unbalanced—with a large number of samples in the majority class and few in the minority class—models tend to achieve high accuracy for the majority class but struggle significantly with minority class classification [27]. This bias occurs because the models have insufficient examples of minority classes from which to learn, causing them to become biased toward the majority class [27].

The Impact of Dataset Limitations on Model Performance

Quantifying the Annotation Burden

The creation of high-quality annotated datasets for plant disease detection represents a substantial resource investment. Industry research indicates that data annotation can consume 50-80% of a computer vision project's budget and extend timelines beyond original schedules [28]. In medical imaging, which shares similar annotation challenges with plant pathology, the specialized expertise required can cost three to five times more than generalist labelers [28]. This annotation tax creates a particular barrier for smaller research teams and agricultural technology startups that can least afford it [28].

The scale of data required for effective model training is substantial. One comprehensive study utilized a dataset of 30,945 images across eight plant types and 35 disease classes to achieve high accuracy detection [14]. Creating datasets of this magnitude requires significant coordination and resource allocation, particularly given the need for expert validation of each annotation.

Performance Gaps Between Laboratory and Field Conditions

Dataset limitations directly translate to performance disparities in real-world applications. Systematic analysis reveals significant accuracy gaps between controlled laboratory conditions (achieving 95-99% accuracy) and field deployment (typically 70-85% accuracy) [1]. Transformer-based architectures demonstrate superior robustness in these challenging conditions, with SWIN achieving 88% accuracy on real-world datasets compared to 53% for traditional CNNs [1].

Class imbalance specifically degrades model performance across key metrics. Studies on the effects of imbalanced training data distributions on Convolutional Neural Networks show that performance consistently decreases with increasing imbalance, with highly imbalanced distributions causing models to default to predicting the majority class [27]. This performance degradation is particularly problematic for rare diseases, where accurate detection is often most critical for preventing widespread crop loss.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Plant Disease Detection Models Across Different Conditions

| Model Architecture | Laboratory Accuracy (%) | Field Accuracy (%) | Performance Drop |

|---|---|---|---|

| SWIN Transformer | 95+ [1] | 88 [1] | 7% |

| Traditional CNN | 95+ [1] | 53 [1] | 42% |

| Custom CNN | 95.62 [14] | Not reported | - |

| InceptionV3 | 98 (tomato) [14] | Not reported | - |

| MobileNet | 100 (multiple) [14] | Not reported | - |

Addressing Class Imbalance: Experimental Approaches and Protocols

Resampling Techniques and Their Efficacy

Multiple methodological approaches have been developed to address class imbalance in plant disease datasets. Resampling techniques include oversampling methods (such as random oversampling, SMOTE, and ADASYN) and undersampling methods (including random undersampling and data cleaning techniques like Edited Nearest Neighbors) [27] [29]. The effectiveness of these approaches varies significantly based on the model architecture and specific application context.

Recent systematic comparisons reveal that oversampling methods like SMOTE show performance improvements primarily with "weak" learners like decision trees and support vector machines, but provide limited benefits for strong classifiers like XGBoost when appropriate probability threshold tuning is implemented [29]. For models that don't return probability outputs, random oversampling often provides similar benefits to more complex SMOTE variants, making it a recommended first approach due to its simplicity [29].

Table 2: Class Imbalance Solution Performance Comparison

| Technique | Best For | Key Advantage | Performance Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Oversampling | Weak learners, non-probability models [29] | Simplicity, computational efficiency | Similar to SMOTE in many cases [29] |

| SMOTE & Variants | Weak learners, multilayer perceptrons [29] | Generates synthetic minority examples | Limited benefit for strong classifiers [29] |

| Random Undersampling | Specific dataset types [29] | Reduces dataset size, computational load | Improves performance in some datasets [29] |

| Instance Hardness Threshold | Random Forests in some cases [29] | Identifies and removes problematic examples | Mixed results across datasets [29] |

| Balanced Random Forests | Imbalanced classification [29] | Integrated sampling during training | Outperformed Adaboost in 8/10 datasets [29] |

| EasyEnsemble | Imbalanced classification [29] | Combines ensemble learning with sampling | Outperformed Adaboost in 10/10 datasets [29] |

Data Augmentation and Synthetic Data Generation

Beyond resampling, data augmentation and synthetic data generation represent powerful approaches to addressing both annotation scarcity and class imbalance. Data augmentation involves artificially boosting the number of data points in underrepresented classes by generating additional data through transformations such as rotation, scaling, or color modification [27]. This approach helps achieve a more balanced dataset without collecting additional images.

Advanced techniques utilize Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to generate synthetic images that can be incorporated into training datasets, balancing class distributions [27]. This strategy has proven particularly beneficial when data collection is difficult or privacy concerns are paramount. In medical imaging, which faces similar challenges to plant disease detection, triplet-based real data augmentation methods have been shown to outperform other techniques [27].

Protocol-Driven Annotation Frameworks

Structured annotation frameworks offer promising approaches to streamlining the annotation process while maintaining quality. The MedPAO framework exemplifies this approach with a Plan-Act-Observe (PAO) loop that operationalizes clinical protocols as core reasoning structures [30]. While developed for medical reporting, this protocol-driven methodology provides a verifiable alternative to opaque, monolithic models that could be adapted for plant disease annotation [30].

This framework employs a modular toolset including concept extraction, ontology mapping, and protocol-based categorization, achieving an F1-score of 0.96 on concept categorization tasks [30]. Expert radiologists and clinicians rated the final structured outputs with an average score of 4.52 out of 5, demonstrating the potential for protocol-driven approaches to enhance annotation quality [30].

Experimental Benchmarking: Methodologies and Results

Comprehensive Model Evaluation Protocols

Large-scale benchmarking studies provide critical insights into model performance across diverse datasets. One comprehensive evaluation implemented and trained 23 models on 18 plant disease datasets for 5 repetitions each under consistent conditions, resulting in 4,140 total trained models [31]. This systematic approach allows for direct comparison of model architectures and identification of best practices for plant disease detection.

The study utilized transfer learning extensively, allowing models to leverage knowledge obtained from previous tasks for new applications, reducing training time and data requirements [31]. For each model-dataset combination, researchers employed both standard transfer learning and transfer learning with additional fine-tuning, enabling assessment of how much specialized training improves performance for specific plant disease detection tasks [31].

Performance Metrics for Imbalanced Data

Proper evaluation metrics are essential when assessing models trained on imbalanced datasets. While accuracy provides an intuitive performance measure, it becomes less reliable with class imbalance [9]. The F1 score, representing the harmonic mean of precision and recall, is particularly appropriate for imbalanced datasets as it balances both false positives and false negatives [9].

In plant disease detection, false negatives (missed infections) are often more critical than false positives, as they represent missed treatment opportunities [9]. However, false positives also warrant consideration due to resource constraints, making the F1 score a balanced metric for optimization [9]. Additional metrics including precision, recall, and balanced accuracy provide complementary insights into model behavior across different classes [9].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for addressing class imbalance in plant disease detection, showing multiple pathways based on dataset characteristics and model selection.

Emerging Solutions and Research Directions

Automated Labeling Technologies

Recent advances in auto-labeling techniques promise to dramatically reduce the annotation bottleneck. Verified Auto Labeling (VAL) pipelines can achieve approximately 95% agreement with expert labels while reducing costs by approximately 100,000 times for large-scale datasets [28]. This approach enables labeling tens of thousands of images in a workday, transforming annotation from a long-running expense to a repeatable batch job [28].

These automated approaches leverage foundation models and vision-language models (VLMs) that excel at open-vocabulary detection and multimodal reasoning [28]. On popular datasets, models trained on VAL-generated labels perform virtually identically to models trained on fully hand-labeled data for everyday objects, with performance gaps only appearing for rare classes where limited human annotation remains beneficial [28].

Transfer Learning and Domain Adaptation

Transfer learning has emerged as a particularly valuable approach for addressing data limitations in plant disease detection. This technique enables the application of deep learning benefits even with limited data by using models pre-trained on extensive and diverse datasets, then fine-tuning them on smaller, more specific datasets [27]. This approach is especially advantageous when data collection is costly or complicated [27].

Large-scale benchmarking demonstrates that transfer learning significantly reduces the data requirements for effective model development while maintaining strong performance across diverse plant species and disease types [31]. The effectiveness of transfer learning varies by model architecture, with some models demonstrating superior adaptability to new domains and disease categories.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Plant Disease Detection Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Public Datasets | PlantVillage [7], PlantDoc [7], Plant Pathology 2020-FGVC7 [7] | Provide benchmark datasets for training and evaluation across multiple plant species and diseases |

| Annotation Tools | Voxel51 FiftyOne [28], Verified Auto Labeling (VAL) [28] | Enable efficient dataset labeling, visualization, and quality assessment with auto-labeling capabilities |

| Class Imbalance Solutions | Imbalanced-Learn [29], SMOTE & variants [27], Random Oversampling/Undersampling [29] | Address class distribution issues through resampling and data generation techniques |

| Model Architectures | CNN (MobileNet, ResNet) [14] [32], Vision Transformers [1], Hybrid Models [1] | Provide base architectures for transfer learning and specialized plant disease detection |

| Evaluation Metrics | F1 Score [9], Balanced Accuracy [9], Precision-Recall Analysis [9] | Enable appropriate performance assessment on imbalanced datasets beyond simple accuracy |

| Domain Adaptation | Transfer Learning Protocols [31], Fine-tuning Methodologies [31] | Facilitate knowledge transfer from general to specific plant disease detection tasks |

The annotation bottleneck and class imbalance challenges in plant disease detection are being addressed through multiple complementary approaches. While traditional resampling methods like SMOTE show limited benefits for strong classifiers, alternative strategies including threshold tuning, cost-sensitive learning, and ensemble methods like Balanced Random Forests and EasyEnsemble demonstrate significant promise [29]. Simultaneously, emerging auto-labeling technologies are dramatically reducing annotation costs and timelines, potentially transforming dataset creation from a major bottleneck to an efficient process [28].

The integration of protocol-driven annotation frameworks, comprehensive transfer learning benchmarks, and appropriate evaluation metrics provides a pathway toward more robust and equitable plant disease detection systems [30] [31]. As these technologies mature, they promise to enhance global food security by enabling more accurate and timely identification of plant diseases across diverse agricultural contexts and resource constraints.

Architectural Deep Dive: CNN, Transformer, and Hybrid Models for Disease Diagnosis

The global agricultural sector faces persistent threats from plant diseases, causing estimated annual losses of 220 billion USD [1]. Rapid and accurate diagnosis is crucial for mitigating these losses and ensuring food security. In recent years, deep learning-based image analysis has emerged as a powerful tool for automated plant disease detection. Among the various architectures, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) like ResNet, EfficientNet, and NASNetLarge have demonstrated remarkable performance. However, selecting the optimal architecture involves navigating complex trade-offs between accuracy, computational efficiency, and practical deployability in resource-constrained agricultural settings.

This guide provides an objective comparison of these prominent CNN architectures, specifically framed within the context of plant disease detection research. By synthesizing current experimental data and detailing methodological protocols, we aim to equip researchers and developers with the evidence needed to select appropriate models for their specific agricultural applications.

The evolution of CNN architectures has progressed from manually designed networks to highly optimized, automated designs. ResNet (Residual Network) introduced the breakthrough concept of skip connections to mitigate the vanishing gradient problem, enabling the training of very deep networks [33]. EfficientNet advanced this further through a compound scaling method that systematically balances network depth, width, and resolution for optimal efficiency [34] [33]. NASNetLarge represents the paradigm shift toward automated architecture design, utilizing Neural Architecture Search (NAS) to discover optimal cell structures through computationally intensive reinforcement learning [35].

For a meaningful comparison in plant disease detection, models are evaluated against multiple criteria: classification accuracy on standard agricultural datasets; computational efficiency measured by parameter count and FLOPs (Floating Point Operations); and practical deployability considering inference speed and model size. These metrics collectively determine a model's suitability for real-world agricultural applications, from cloud-based analysis to mobile and edge deployment.

Performance Benchmarking in Plant Disease Detection

Quantitative Comparison Across Architectures

Experimental results across multiple studies reveal distinct performance characteristics for each architecture. The following table summarizes key metrics from controlled experiments on plant disease datasets:

Table 1: Performance Benchmarking of CNN Architectures on Plant Disease Detection Tasks

| Architecture | Top-1 Accuracy (%) | Number of Parameters (Millions) | FLOPs (Billion) | Inference Speed (Relative) | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ResNet-50 [1] [11] | 95.7 (PlantVillage) | 25.6 | ~4.1 | Medium | Baseline comparisons, General-purpose detection |

| EfficientNet-B0 [33] [36] | 94.1 (101-class dataset) | 5.3 | 0.39 | High | Mobile/edge deployment, Resource-constrained environments |

| EfficientNet-B1 [36] | 94.7 (101-class dataset) | 7.8 | 0.70 | Medium-High | Balanced accuracy-efficiency trade-off |

| EfficientNet-B2 [37] | 99.8 (Brain MRI - analogous task) | 9.2 | 1.0 | Medium | High-accuracy requirements with moderate resources |

| EfficientNet-B7 [33] | 84.3 (ImageNet) | 66 | 37 | Low | Maximum accuracy, Server-based analysis |

| NASNetLarge [35] | 85.0 (Five-Flowers) | 88 | ~- | Very Low | Research benchmark, Computational exploration |

Cross-Dataset Generalization Performance

A critical metric for real-world agricultural applications is model performance across diverse datasets, which indicates generalization capability. The following table compares architecture performance when trained and validated on different plant disease datasets:

Table 2: Cross-Dataset Generalization Performance for Plant Disease Detection

| Architecture | PlantVillage Accuracy (%) [11] [36] | Plant Disease Expert Accuracy (%) [11] | Cross-Domain Validation Rate (CDVR) [11] | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ResNet-50 | 95.7 | - | - | Strong baseline performance |

| Mob-Res (MobileNetV2 + ResNet) | 99.47 | 97.73 | Competitive | Hybrid architecture example |

| EfficientNet-B0 | ~99.0 [36] | - | - | Excellent performance with minimal parameters |

| EfficientNet-B1 | ~99.0 [36] | - | - | Optimal balance for mobile applications |

| Custom Lightweight CNN [11] | 99.45 | - | Superior | Domain-specific optimization advantages |

Efficiency-Accuracy Trade-off Analysis

For field deployment, the relationship between computational requirements and accuracy is paramount. Recent research highlights that while transformer-based architectures like SWIN can achieve up to 88% accuracy on real-world datasets compared to 53% for traditional CNNs, their computational demands often preclude mobile deployment [1]. EfficientNet variants consistently provide the best efficiency-accuracy balance, with EfficientNet-B1 achieving 94.7% classification accuracy across 101 disease classes while remaining suitable for resource-constrained devices [36].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Evaluation Framework

To ensure fair comparison across architectures, researchers should adhere to standardized experimental protocols. Based on methodology from benchmark studies [38] [11], the following workflow provides a robust framework for evaluating plant disease detection models:

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for benchmarking CNN architectures in plant disease detection.

Dataset Specifications and Preparation

Consistent data preparation is essential for meaningful comparisons. Key publicly available datasets include:

- PlantVillage: Contains 54,036 images across 14 plants and 26 diseases (38 total categories) [7]. Though widely used, most images have laboratory or single backgrounds, limiting real-world generalization testing.

- PlantDoc: Features images captured in natural field conditions, providing better diversity for testing robustness to environmental variables [36] [7].

- Custom Combined Datasets: Recent studies create comprehensive benchmarks by merging multiple datasets. One study combined PlantDoc, PlantVillage, and PlantWild to create a dataset spanning 101 disease classes across 33 crops [36].

Data preprocessing should standardize image sizes to each model's optimal input dimensions (224×224 for ResNet, 480×480 for EfficientNet, 331×331 for NASNetLarge) [39] [35], with pixel values normalized to [0,1]. Augmentation strategies should include rotation, flipping, color jittering, and CutMix [38] to improve model robustness.

Training Protocols and Hyperparameter Settings

Based on experimental reports, the following training protocols yield reproducible results:

- Optimizer: RMSProp with decay=0.9 and momentum=0.9 for EfficientNet; Adam or SGD for other architectures [34] [38]

- Learning Rate: Initial rate of 0.256 for EfficientNet, decaying by 0.97 every 2.4 epochs; adaptive learning rate strategies can improve convergence [34] [37]

- Regularization: Weight decay (1e-5) and dropout (0.2-0.7 proportional to model size) [34]

- Batch Size: Adjust based on GPU memory (16-128 typically)

- Training Paradigm: Compare transfer learning (pretrained on ImageNet) versus scratch training, as the performance gap can be significant for smaller datasets [38]

Technical Architecture and Design Principles

Core Architectural Components

The benchmarked architectures incorporate distinct design innovations that explain their performance characteristics:

Figure 2: Architectural innovations and design principles across CNN families.

Compound Scaling in EfficientNet

EfficientNet's efficiency advantage stems from its compound scaling method, which coordinates scaling across network dimensions according to the equations:

- Depth: ( d = \alpha^\phi )

- Width: ( w = \beta^\phi )

- Resolution: ( r = \gamma^\phi )

- Constraints: ( \alpha \cdot \beta^2 \cdot \gamma^2 \approx 2 ) and ( \alpha \geq 1, \beta \geq 1, \gamma \geq 1 )

Where ( \alpha, \beta, \gamma ) are constants determined via grid search (typically α=1.2, β=1.1, γ=1.15), and φ is the user-defined compound coefficient that controls model scaling [34] [33]. This principled approach enables EfficientNet to achieve better accuracy than models scaled along single dimensions, with up to 8.4x smaller parameter count and 16x fewer FLOPs compared to ResNet [34].

Neural Architecture Search in NASNet

NASNet employs a sophisticated automated design process where an RNN controller generates architectural "blueprints" through reinforcement learning. The process involves:

- Controller Operation: An RNN samples architectural configurations describing how to connect operations (convolutions, pooling, identity mappings)

- Cell Structure: The search discovers two cell types - normal cells (preserve spatial dimensions) and reduction cells (reduce spatial dimensions)

- Reward Signal: The validation accuracy of child networks trained with sampled architectures serves as the reward signal

- Parameter Optimization: The controller updates its parameters using REINFORCE or proximal policy optimization to maximize expected accuracy [35]

While effective, this process is computationally intensive, requiring approximately 500 GPUs for four days in the original implementation [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers replicating these benchmarks or developing new plant disease detection models, the following tools and resources are essential:

Table 3: Essential Research Tools and Resources for Plant Disease Detection Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools & Platforms | Purpose & Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Datasets | PlantVillage, PlantDoc, Plant Pathology 2020-FGVC7 | Training and evaluation of models | Publicly available on Kaggle and academic portals [7] |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | TensorFlow/Keras, PyTorch | Model implementation and training | Open-source with pre-trained models available [39] [35] |

| Experimental Repositories | GitHub (Papers with Code) | Reference implementations and baselines | Public repositories with code for cited studies |

| Evaluation Metrics | Accuracy, F1-Score, FLOPs, Parameter Count | Standardized performance assessment | Custom implementations based on research requirements [38] |

| Explainability Tools | Grad-CAM, Grad-CAM++, LIME | Model interpretability and visualization | Open-source Python packages [37] [11] |