Speed Breeding 3.0: Accelerating Crop Improvement for Food Security and Climate Resilience

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of speed breeding (SB), an innovative set of techniques that leverage controlled environments to accelerate plant generation cycles.

Speed Breeding 3.0: Accelerating Crop Improvement for Food Security and Climate Resilience

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of speed breeding (SB), an innovative set of techniques that leverage controlled environments to accelerate plant generation cycles. Tailored for researchers and scientists, we explore the foundational principles of SB, detailing how manipulation of photoperiod, light quality, and temperature can achieve 4-6 crop generations annually. The content covers advanced methodologies, including integration with genomic selection and CRISPR-Cas9, and addresses critical challenges such as genotype dependence and high operational costs. Through comparative validation with traditional breeding methods and case studies on staple crops, this review synthesizes how SB is revolutionizing breeding pipelines to enhance genetic gain and develop climate-resilient cultivars, directly addressing global food security demands.

The Foundation of Speed Breeding: Principles, History, and Core Concepts

Speed breeding represents a transformative technological approach in plant science that utilizes controlled environmental conditions to dramatically accelerate plant growth and development cycles. This methodology addresses one of the most significant bottlenecks in conventional plant breeding: the extended time required to develop new crop varieties. With the global population projected to reach 10 billion by 2050 and climate change exacerbating agricultural challenges, the slow pace of traditional breeding—often taking 8-15 years to develop and release a new variety—is no longer adequate to meet future food security demands [1] [2]. Speed breeding has emerged as a critical innovation to compress breeding timelines, enabling researchers to achieve up to 4-6 generations of crops like rice, wheat, and barley annually compared to the 1-2 generations possible through conventional field-based methods [1] [3].

The fundamental principle underlying speed breeding involves the precise manipulation of environmental factors—including photoperiod, light spectrum, temperature, humidity, and nutrient regimes—to optimize photosynthetic efficiency and promote rapid progression through developmental stages from seed to seed [4] [5]. Unlike genetic modification approaches, speed breeding does not alter the plant's DNA but instead creates optimized growing conditions that trigger early flowering and seed maturation, thereby significantly reducing generation times [1]. This approach has evolved from early experiments with artificial lighting 150 years ago to sophisticated protocols developed by research institutions worldwide, including NASA's space agriculture research, the International Rice Research Institute's (IRRI) Speed Breeding 3.0 framework, and specialized protocols for crops ranging from staple cereals to nutrient-dense millets [3] [2] [5].

Core Objectives of Speed Breeding

Accelerating Genetic Gain and Breeding Cycles

The primary objective of speed breeding is to compress the time required for each breeding cycle, thereby accelerating genetic gain—the measurable improvement in crop performance per unit time. Traditional breeding methods typically allow only one or two generations annually, creating a significant delay between initial crosses and the development of stable lines ready for commercial release [1]. Speed breeding protocols enable researchers to achieve up to five or six generations per year for key crops such as rice and wheat, effectively reducing variety development time by 50% or more [1] [3]. For instance, researchers at Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences and Technology (SKUAST) in Kashmir have demonstrated that speed breeding can shorten the typical 8-year variety development process by several years, with additional reductions in regulatory approval timelines [1].

This acceleration is particularly valuable for pre-breeding activities—the process of incorporating desirable traits from unadapted genetic resources into breeding-ready materials. Conventional pre-breeding often requires 3-4 years to develop lines containing superior haplotypes in elite genetic backgrounds [3]. Through speed breeding, this timeline can be compressed to less than 2 years, ensuring that new sets of lines are synchronized with product concepts before initiating new breeding cycles [3]. The integration of speed breeding with genomic selection and marker-assisted selection further enhances selection intensity and accuracy, creating a synergistic effect that maximizes genetic gains throughout the breeding pipeline [3].

Enhancing Climate Resilience in Crops

Speed breeding enables the rapid development of climate-resilient crop varieties capable of withstanding biotic and abiotic stresses intensified by climate change. Researchers can utilize speed breeding protocols to quickly introgress tolerance traits for diseases, drought, heat, and salinity into elite genetic backgrounds, creating varieties adapted to increasingly volatile growing conditions [1] [6]. At SKUAST in Kashmir, scientists are prioritizing the development of rice varieties with enhanced resistance to blast and bakanae diseases, alongside improved cold tolerance during early growth stages—traits critically important for sustainable production in the region [1].

The SpeedScan component of IRRI's Speed Breeding 3.0 framework exemplifies this objective by combining speed breeding environments with machine learning and deep learning models to phenotype stable traits and predict performance in untested populations [3]. This approach facilitates the development of "ideotypes"—ideal plant types optimized for future climate scenarios—by screening current varieties under simulated future climate conditions [3]. Similarly, the SpeedWild protocol focuses on tapping into the vast, unutilized genetic diversity of wild relatives to broaden the genetic base of cultivated varieties, introducing valuable genes for enhanced resilience that have been lost through domestication bottlenecks [3].

Facilitating Rapid Trait Stacking and Gene Pyramiding

Speed breeding provides an efficient platform for stacking multiple desirable traits through rapid cycling of breeding populations, enabling researchers to combine disease resistance, quality parameters, and stress tolerance in a single genetic background. The accelerated generational turnover allows for more efficient backcrossing and selection of complex trait combinations that would require decades using conventional methods [3] [2]. The SpeedEdit component of Speed Breeding 3.0 seamlessly integrates speed breeding with advanced genome editing technologies, including Multiplex Genome Editing (MGE), gene drive, and CRISPR/Cas9, to facilitate precise and rapid genetic modifications [3].

This integration enables efficient trait stacking, such as combining multiple stress tolerances, through technologies like BREEDIT that would be impractical with slower conventional breeding cycles [3]. For example, MGE could potentially transfer C4 photosynthetic genes from maize to rice, significantly improving its water and nitrogen use efficiency under high CO2 and temperature conditions—a complex multi-gene engineering project that would benefit enormously from accelerated generational cycling [3]. The ability to rapidly fix these introduced traits through successive generations under controlled conditions makes speed breeding an invaluable component of modern crop genetic engineering pipelines.

Quantitative Analysis of Speed Breeding Efficiency

Table 1: Generation Time Comparison Between Conventional Breeding and Speed Breeding

| Crop Species | Conventional Generations/Year | Speed Breeding Generations/Year | Generation Time Reduction | Research Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice (Kashmir) | 1-2 | 4-6 | 60-75% | [1] |

| Finger Millet | 1-2 | 4-5 | 28-54 days across maturity groups | [5] |

| Wheat | 1-2 | 4-6 | ~77 days per generation | [2] |

| Maize | 1-2 | Not specified | Significant with doubled haploid integration | [1] |

| Barley | 1-2 | 4-6 | Similar to wheat | [4] |

Table 2: Speed Breeding Facility Environmental Parameters for Different Crops

| Parameter | Finger Millet Protocol | IRRI Rice Protocol | General Cereal Protocol | Impact on Development |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Photoperiod | 9 hours | Customized light recipes | 22 hours (long-day crops) | Induces early flowering |

| Temperature | 29±2°C | Precise control | 22°C day/17°C night | Optimizes metabolism |

| Light Intensity | LED 9-watt bulbs | Full-spectrum PPFD lights | High-intensity LED | Maximizes photosynthesis |

| Relative Humidity | 70% | Optimized levels | Controlled levels | Prevents stress |

| Plant Density | 105 plants/1.5 sq. ft. | High-density planting | 1000 plants/m² (cereals) | Space optimization |

Application Notes: Speed Breeding 3.0 Framework

Core Components of Speed Breeding 3.0

The International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) has pioneered Speed Breeding 3.0 as a comprehensive, inclusive, and adaptable framework designed for all crops regardless of their growth cycle [3]. This advanced strategy represents a critical initiative supporting OneCGIAR's overarching goal to unify capabilities, knowledge, and resources toward addressing climate change and ensuring global food security [3]. Unlike earlier iterations that primarily focused on extended photoperiods for long-day crops, Speed Breeding 3.0 accommodates larger populations and wider germplasm diversity, including landraces, wild relatives, and breeding lines with variable growth durations [3].

The framework integrates fundamental understanding in speed breeding with customized, stage-specific light recipes and strategic application of various growth parameters to synchronize growth and induce flowering [3]. This innovative approach maximizes breeding program efficiency, accelerates genetic gains, and promotes inclusive, sustainable crop improvement across diverse agricultural contexts. The system leverages advanced photobiological tools to precisely control environmental parameters including light spectrum, intensity, photoperiod, temperature, and hormonal regulation, enabling up to six generations annually for vital crops like wheat, rice, and barley [3].

Integrated Speed Breeding Workflows

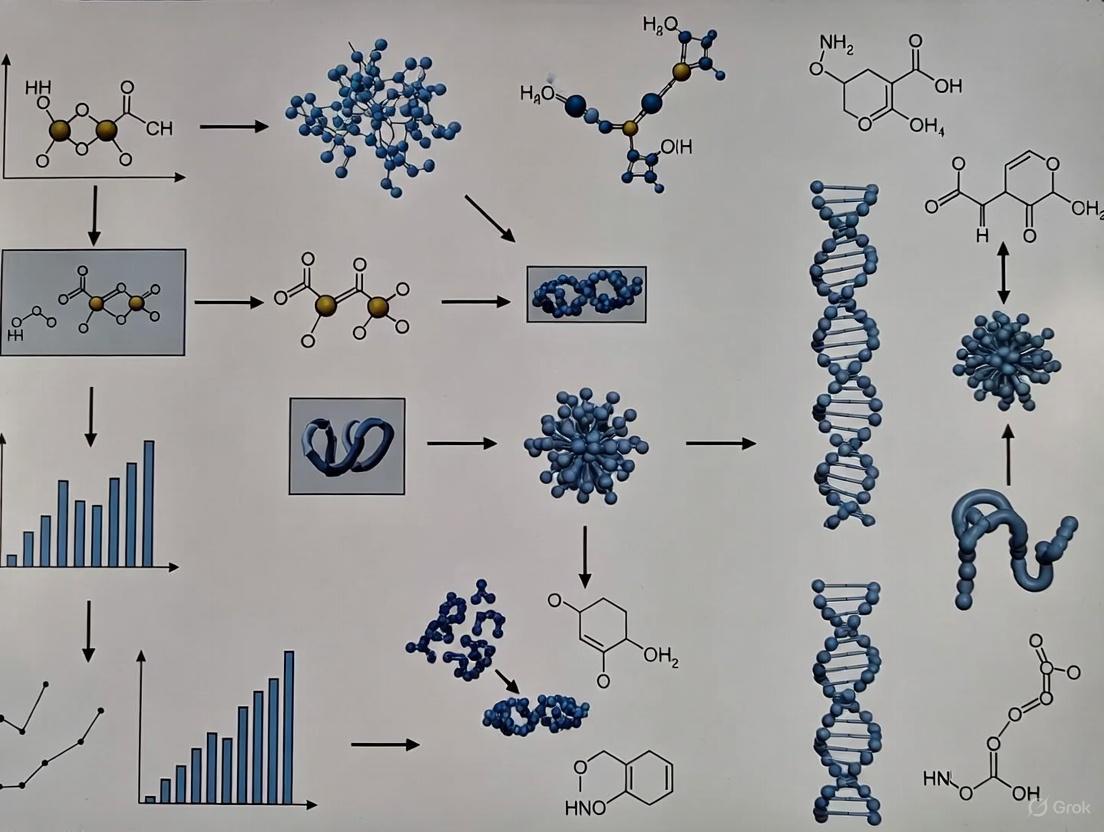

Diagram 1: Integrated Speed Breeding 3.0 Workflow showing the convergence of different acceleration technologies in a modern breeding program.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Speed Breeding Protocol for Cereal Crops (Rice/Wheat)

Objective: Achieve 4-6 generations per year through controlled environment optimization [1] [3].

Materials and Equipment:

- Controlled environment growth chambers or customized speed breeding facilities

- Full-spectrum LED lighting systems with photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) control

- Temperature and humidity control systems

- High-density planting trays (50-105 wells per tray)

- Automated irrigation systems (ebb-and-flow recommended)

- Environmental monitoring sensors (light, temperature, humidity, CO₂)

Procedure:

- Seed Preparation and Sowing:

- Select high-quality seeds from desired breeding materials

- Sow seeds in high-density trays (1000 plants/m² for cereals) containing sterile growing medium [2]

- Maintain optimal moisture for germination

Early Growth Phase (0-14 days):

- Maintain temperature at 22±2°C during light periods and 17±2°C during dark periods for temperate cereals [2]

- Provide continuous light (22 hours) for long-day crops or customized photoperiods for day-neutral/short-day species [3] [2]

- Maintain CO₂ levels at 400-500 ppm to enhance photosynthetic efficiency

- Implement high-density planting (105 plants per 1.5 sq. ft. demonstrated for finger millet) [5]

Vegetative to Reproductive Transition (14-35 days):

- Adjust light spectrum using customized "light recipes" to promote flowering

- Apply nutrient solutions (e.g., 0.17% Hoagland's No. 2 solution spray weekly) [5]

- Implement restricted irrigation to minimize plant height and accelerate development

- Monitor plant development daily for flowering initiation

Pollination and Seed Development (35-60 days):

- Facilitate controlled pollination when flowers are receptive

- Maintain optimal temperature and humidity during seed set

- Continue nutrient application until seed filling is complete

Harvest and Seed Processing (60-70 days):

- Harvest seeds at physiological maturity using forced desiccation if necessary

- Process seeds to break dormancy through appropriate treatments

- Immediately resow selected seeds for the next generation cycle

Troubleshooting:

- If flowering is delayed, adjust red:far-red light ratios and photoperiod

- For poor seed set, optimize humidity during flowering and ensure proper pollination

- If fungal issues arise, ensure proper air circulation and sterilize growing media

Protocol for Integration with Genomic Selection

Objective: Combine speed breeding with genomic selection to enhance genetic gain per unit time [7] [3].

Procedure:

- Initial Genotyping:

- Extract DNA from parental lines and early generations (F₂)

- Perform genome-wide sequencing or SNP genotyping

- Develop training population for genomic selection models

Rapid Cycling with Simultaneous Genotyping:

- Advance generations under speed breeding conditions

- Perform seed chipping for DNA extraction without compromising germination

- Conduct genomic selection at each generation based on genomic estimated breeding values (GEBVs)

- Select superior genotypes for continued rapid cycling

Field Validation:

- After 3-4 generations of speed breeding coupled with genomic selection, advance selected lines to field trials

- Validate predictions and refine genomic selection models

- Integrate data into subsequent cycles for improved accuracy

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Speed Breeding Implementation

| Item Category | Specific Products/Models | Function in Speed Breeding | Protocol Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lighting Systems | Full-spectrum PPFD LED lights, Narrow blue + narrow amber LED mixtures | Optimize photosynthesis and control photoperiod; specific wavelengths influence flowering | 22h light for long-day crops; 9h for short-day crops like finger millet [3] [5] |

| Nutrient Solutions | Hoagland's No. 2 solution (0.17%), Basacote + NPK (20:20:20) formulations | Provide balanced nutrition in restricted root zones; spray application preferred to minimize losses | Weekly foliar application; supplementation when leaves show pale green coloration [5] |

| Growth Substrates | Sterilized soil:sand:vermicompost (3:2:1 ratio), Hydroponic ebb-and-flow systems | Ensure proper aeration and drainage in high-density planting; prevent pathogen introduction | Soil mixture replaced every 3-4 generations to replenish depleted nutrients [1] [5] |

| Environmental Controllers | Programmable Logic Controllers (PLC), Temperature and humidity sensors | Maintain precise environmental conditions (29±2°C, 70% RH for finger millet) | Automated control of heating, cooling, and humidity systems [5] |

| High-Density Trays | 105-well and 50-well nursery trays (HIPS material) | Maximize plant capacity per square meter; enable bottom-up irrigation | 105 plants per 1.5 sq. ft. optimal for finger millet without significant competition effects [5] |

Integration with Advanced Breeding Technologies

Convergence with High-Throughput Phenotyping

The integration of speed breeding with high-throughput phenotyping (HTP) technologies creates a powerful synergy that addresses both the time and phenotyping bottlenecks in conventional breeding [8]. Advanced phenotyping platforms utilizing digital imaging systems, chlorophyll fluorescence sensors, and high-resolution 3D scanners can capture essential metrics like plant height, leaf area, canopy structure, and chlorophyll content throughout the accelerated growth cycle [8]. This integration enables non-destructive, continuous monitoring of plant development, allowing researchers to correlate genetic potential with observable traits under controlled stress conditions.

The SpeedScan component of Speed Breeding 3.0 exemplifies this integration by combining speed breeding environments with machine learning and deep learning models to phenotype stable traits and predict performance in untested populations [3]. This approach significantly reduces the need for extensive field phenotyping, saving both time and resources while maintaining accuracy. For shoot phenomics, technologies such as 3D imaging analyze canopy architecture and biomass, revealing correlations between canopy traits and drought resilience [8]. For root phenomics—traditionally challenging due to the subterranean nature of roots—advanced imaging technologies like Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), Computed Tomography (CT), and X-ray tomography enable non-invasive observation of root architecture, providing insights into stress tolerance mechanisms [8].

Synergy with Genomic and Biotechnology Tools

Diagram 2: Technology Synergies in Modern Speed Breeding Programs showing bidirectional relationships between speed breeding and complementary biotechnology tools.

Speed breeding creates particularly powerful synergies when integrated with genomic selection and gene editing technologies. The accelerated generational turnover enables more rapid fixation of desirable alleles identified through genomic selection, significantly enhancing the rate of genetic gain [7]. AI-powered genomic selection analyzes massive genomic datasets to associate genetic markers with desirable traits, predicting breeding values of potential parent lines without extensive phenotyping of every plant generation [7]. When combined with speed breeding, these predictive models allow breeders to focus efforts only on the most promising genotypes, slashing trial and error and shrinking breeding cycles from years to just seasons [7].

Similarly, the integration of speed breeding with gene editing technologies like CRISPR-Cas9 through the SpeedEdit framework facilitates precise and rapid genetic modifications, accelerating the introduction of complex traits using multiplex genome editing tools [3]. This approach enables efficient trait stacking—combining multiple stress tolerances or quality traits—that would be impractical with slower conventional breeding cycles [3]. The accelerated generations allow for more efficient removal of CRISPR machinery and stabilization of edited loci, addressing regulatory concerns more rapidly than conventional approaches.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite its transformative potential, speed breeding implementation faces several significant challenges that must be addressed for wider adoption. The most substantial barrier is the high energy consumption associated with maintaining controlled environments, particularly in regions with extreme climatic conditions [1]. Researchers in northern India report that maintaining stable environmental conditions requires constant operation of air conditioners, heaters, humidifiers, and LED lighting, leading to substantial power usage [1]. This challenge is compounded by the need for technical expertise to maintain sophisticated speed breeding chambers and troubleshoot system failures [1].

Future developments in speed breeding technology are likely to focus on increasing energy efficiency through innovations in solar power integration, more efficient LED lighting systems, and automated climate control systems [1]. The development of more cost-effective protocols, such as Chem-RGA (chemical-mediated rapid generation advancement) that utilizes specific chemical or hormonal treatments to induce flowering in conventional field conditions, offers promise for resource-limited settings [3]. Additionally, the democratization of speed breeding through consortium-based support services for National Agricultural Research and Extension Systems (NARES) and private companies will be crucial for global adoption [3].

As climate change intensifies, speed breeding will play an increasingly critical role in developing climate-resilient crops. The technology's ability to rapidly introgress adaptive traits and create varieties tailored to specific environmental conditions makes it an indispensable tool for building agricultural resilience. With continued refinement and integration with complementary technologies, speed breeding represents a paradigm shift in crop improvement—from a reactive process to a proactive strategy that enables agriculture to adapt at the pace of climate change itself.

Speed breeding (SB) represents a paradigm shift in agricultural science, enabling the rapid development of new crop varieties by significantly shortening breeding cycles. This approach utilizes controlled environments to optimize plant growth conditions, accelerating generation turnover from typically 1-2 generations per year to 4-6 generations annually for many key crops [9] [10]. The technology has emerged as a critical tool for addressing global food security challenges posed by population growth and climate change, with its foundations tracing back to space exploration research conducted by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) [11].

Historical Context and NASA Origins

NASA's Pioneering Work

The conceptual foundation of speed breeding was established through NASA's Controlled Ecological Life Support Systems (CELSS) program in the 1980s [11]. NASA scientists faced the unique challenge of developing efficient plant growth systems for space missions where resources are extremely limited and time is critical. Their initial research focused on understanding how manipulated light cycles could influence plant development and generation times.

Key NASA Milestones:

- 1980s: Initial experiments with accelerated plant growth cycles began

- 1992: First successful implementation of extended photoperiods to accelerate wheat breeding [11]

- Key Investigators: Dr. Gary Stutte served as a principal investigator, demonstrating that light manipulation could significantly reduce time between wheat generations [11]

Transition to Terrestrial Applications

The transition from space-focused research to terrestrial crop improvement began in the late 1990s when Australian scientists recognized the technology's potential for Earth-based agriculture [11]. Dr. Lee Hickey and his team at the University of Queensland played a pivotal role in adapting and developing these protocols for various crops starting in 2001 [11]. The first published results demonstrating successful application in wheat emerged in 2007, followed by a landmark paper in Nature Plants in 2017 that detailed standardized speed breeding protocols [11].

Fundamental Principles of Speed Breeding

Physiological Foundations

Speed breeding operates on several core physiological principles that enable accelerated plant development:

Photoperiod Manipulation: By extending daily light exposure, plants receive increased photosynthetic accumulation, altering their developmental programming to hasten flowering and maturity [11]. This approach effectively manipulates the plant's photoperiodic responses, which are governed by photoreceptor families that help plants respond to extracellular environmental factors [9].

Circadian Rhythm Modification: Extended photoperiods directly influence plants' internal clocks, potentially triggering early flowering responses in many species [11]. Light impacts the molecular mechanisms of plant development, with changes in gene expression profiles in response to light documented in model species like Arabidopsis and rice [9].

Hormonal Regulation: Optimized light conditions influence plant hormone production, particularly gibberellins and auxins, which can accelerate growth and developmental transitions [11].

Environmental Optimization Components

Successful speed breeding protocols integrate multiple environmental parameters that work synergistically to accelerate plant development:

Table 1: Key Environmental Parameters for Speed Breeding

| Parameter | Typical Range | Physiological Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Photoperiod | 22 hours light/2 hours dark (long-day crops); Variable for short-day crops [11] [12] | Triggers early flowering; enhances photosynthetic accumulation |

| Light Intensity | 400-800 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹ PAR [11] [12] | Maximizes photosynthesis without causing light stress |

| Light Spectrum | Enhanced red-blue ratio (2R>1B) for rice; Full-spectrum LED [9] [12] | Optimizes photoreceptor activation for flowering |

| Temperature | 22-32°C (species-dependent) [11] [12] | Maintains optimal metabolic activity |

| Relative Humidity | 60-70% [11] [12] | Reduces transpirational stress |

| CO₂ Concentration | 400-450 ppm [11] | Enhances photosynthetic efficiency |

Evolution of Speed Breeding Protocols

Protocol Refinement and Diversification

Since its initial development, speed breeding methodology has undergone significant refinement and diversification:

2010-2015: Researchers developed optimized light spectra and intensities for different crop species, recognizing that specific wavelength combinations could further accelerate development [11]. Light-emitting diodes (LEDs) became the preferred light source due to their energy efficiency, spectral control, and longevity [9].

2017-2018: Standardized protocols were published, enabling six generations annually for spring wheat, barley, chickpea, and pea, and four generations for rapeseed [10]. This period also saw the development of the first commercial wheat variety (DS Faraday) using speed breeding technology [12].

2018-Present: Protocol development expanded to include short-day crops like soybean, rice, and amaranth through crop-specific light adjustments [9] [12]. Integration with genomic selection, CRISPR-Cas9 technology, and high-throughput phenotyping became more prevalent [9] [6].

Representative Protocol: SpeedFlower for Rice

The SpeedFlower protocol represents a sophisticated example of modern speed breeding implementation for a critical short-day crop:

Key Components:

- Light Spectrum: High red-to-blue ratio (2R>1B) followed by green, yellow, and far-red light [12]

- Photoperiod Strategy: 24-hour long day for initial 15 days of vegetative phase, transitioning to 10-hour short day photoperiod [12]

- Temperature Regime: 32/30°C day/night temperatures with 65% humidity [12]

- Light Intensity: 800 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹ PAR [12]

- Generation Time: 58-71 days, enabling 5.1-6.3 generations annually [12]

Acceleration Techniques:

- Use of prematurely harvested seeds coupled with gibberellic acid treatment reduced maturity duration by 50% [12]

- Validation across 198 diverse rice accessions confirmed broad applicability [12]

Figure 1: Historical Evolution of Speed Breeding Protocols

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of speed breeding requires specific materials and reagents optimized for accelerated plant development:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Speed Breeding

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Growth Media | 70% peat moss, 20% vermiculite, 10% perlite; pH 6.0-6.5 [11] | Provides optimal root aeration and nutrient retention |

| Nutrient Solutions | Modified Hoagland's solution; EC: 1.5-2.0 mS/cm [11] | Delivers balanced mineral nutrition for accelerated growth |

| Light Systems | Full-spectrum LED with enhanced blue (450nm) and red (660nm) wavelengths; Far-red (735nm) capability [9] [12] | Controls photoperiod and spectral quality to manipulate flowering |

| Plant Growth Regulators | Gibberellic acid [12] | Promotes germination and flowering; reduces maturation time |

| Sterilization Agents | 1% sodium hypochlorite solution [11] | Surface sterilization of seeds to prevent microbial contamination |

| CO₂ Supplementation | Food-grade CO₂ cylinders with regulators [11] [12] | Maintains optimal CO₂ levels (400-450 ppm) for photosynthesis |

| Hydration Systems | Automated irrigation/drip systems [11] [12] | Ensures consistent moisture availability for rapid growth |

Integration with Modern Breeding Technologies

Contemporary speed breeding does not operate in isolation but functions as a synergistic component within broader crop improvement pipelines:

Genomic Integration

Speed breeding has been successfully integrated with genomic selection and marker-assisted selection, allowing breeders to rapidly fix desirable genetic combinations while maintaining selection accuracy [9] [13]. This integration follows the breeder's equation (ΔG = (σa)(i)(r)/l), where reducing generation time (l) directly enhances genetic gain [12].

High-Throughput Phenotyping

The controlled environments used in speed breeding are ideal for implementing high-throughput phenotyping technologies [13] [6]. Automated imaging systems can capture data on plant architecture, growth rates, and stress responses, generating large datasets for predictive modeling and selection decisions [13].

Gene Editing and Transformation

Speed breeding protocols have been incorporated into genetic engineering and gene editing pipelines, significantly reducing the time required to develop and evaluate transgenic or genome-edited lines [6]. This application is particularly valuable for stacking multiple traits or evaluating gene function.

Figure 2: Speed Breeding Workflow in Modern Crop Improvement

Application Notes and Technical Considerations

Crop-Specific Optimization

Different crop species require tailored speed breeding protocols due to varying physiological responses:

Long-Day Crops (wheat, barley, chickpea): Respond well to extended photoperiods (22 hours light), achieving up to six generations annually [9] [10].

Short-Day Crops (rice, soybean, amaranth): Require more complex light regimes, often incorporating specific spectral ratios and transitional photoperiods (e.g., long days during vegetative stage followed by short days for flowering) [9] [12].

Winter Crops (winter wheat, winter barley): Benefit from "speed vernalization" protocols that combine accelerated cold treatment with extended photoperiods, enabling up to five generations annually [9].

Troubleshooting Common Challenges

Poor Seed Set: Can be addressed by increasing air circulation to promote pollen dispersal and optimizing temperature during flowering [11].

Plant Stress Symptoms: Leaf chlorosis may require adjustment of nutrient solutions or light intensity; stunted growth may indicate root health issues or suboptimal environmental parameters [11].

Genotype-Specific Responses: Some genotypes within species may not respond as expected to standard protocols, necessitating additional optimization [12].

The evolution of speed breeding from its NASA origins to contemporary sophisticated protocols represents a remarkable example of technology transfer with profound implications for global food security. By systematically manipulating photobiological and environmental parameters, researchers can dramatically accelerate crop breeding cycles while maintaining genetic gain. The ongoing integration of speed breeding with genomic technologies, high-throughput phenotyping, and gene editing continues to enhance its efficiency and applicability across diverse crop species. As climate change and population growth intensify pressure on global food systems, speed breeding protocols offer a powerful tool for developing resilient crop varieties with unprecedented speed.

Genetic and Epigenetic Considerations in Accelerated Growth Environments

Speed breeding (SB) represents a transformative approach in plant sciences, significantly accelerating plant development and generation turnover. By utilizing controlled environments to optimize light, temperature, and other growth factors, SB enables the production of up to six generations per year for crops like spring wheat, barley, chickpea, and pea, and four generations for rapeseed [10]. This dramatic acceleration facilitates the rapid development of pure homozygous lines, a process that traditionally requires 4-6 years, compressing it into approximately one year for many species [10]. Within these accelerated growth environments, a complex interplay of genetic and epigenetic factors governs plant development, stress responses, and trait stability. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for leveraging SB techniques effectively in crop improvement programs, particularly as breeders face the dual challenges of climate change and global food security [10] [14].

Genetic Considerations in Speed Breeding

Genetic Diversity and Accelerated Selection

The foundation of any successful breeding program lies in genetic diversity. In speed breeding systems, maintaining and exploiting this diversity is paramount for developing improved cultivars. The rapid generation advancement in SB creates opportunities for enhanced selection intensity and reduced recombination intervals, potentially accelerating genetic gain. However, the compressed lifecycle necessitates careful management of genetic resources to prevent unintended selection for SB-adapted but agronomically undesirable traits [15].

Molecular markers have become indispensable tools for tracking desirable alleles through breeding generations. In SB, marker-assisted selection (MAS) assumes even greater importance by enabling early selection decisions without waiting for phenotypic expression, which is particularly valuable for traits expressed late in development or requiring specific environmental triggers [15] [16]. For complex quantitative traits controlled by multiple genes, SB integrated with MAS enables researchers to rapidly fix desirable QTL combinations while maintaining genetic diversity for other traits.

QTL Mapping and Gene Discovery in Accelerated Environments

Quantitative trait loci (QTL) mapping identifies genomic regions associated with complex traits of agricultural importance. Traditional QTL mapping requires developing segregating populations and evaluating them across multiple environments and seasons—a process that can take several years. Speed breeding dramatically accelerates this process by enabling rapid generation advancement, allowing researchers to develop mapping populations in a fraction of the conventional time [17].

Studies in maize have demonstrated the efficacy of combining high-density linkage maps with transcriptomic profiling to identify stable QTLs and candidate genes for yield-related traits. For instance, research has confirmed stable QTLs for grain weight on chromosomes 2, 5, 7, and 9, with differentially expressed genes within these intervals providing candidate genes for further functional characterization [17]. Similar approaches can be extended to other crops, with SB accelerating both population development and trait evaluation.

Table 1: Stable QTLs for Grain Weight in Maize Identified Through High-Density Mapping

| QTL Name | Chromosome | LOD Score | Phenotypic Variation Explained (%) | Candidate Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| qKW-7 | 7 | 3.1-7.4 | 4.5-25.6 | 8 DEGs identified |

| qEW-9 | 9 | 3.0-6.2 | 5.8-18.3 | 5 DEGs identified |

| qGWP-6 | 6 | 4.1-5.8 | 6.2-15.7 | 3 DEGs identified |

| qGWP-10 | 10 | 3.5-6.1 | 5.3-14.9 | 6 DEGs identified |

Adapt from citation [17]

Epigenetic Considerations in Speed Breeding

Epigenetic Regulation and Environmental Response

Epigenetics refers to heritable changes in gene expression that occur without alterations to the DNA sequence itself. DNA methylation—the addition of methyl groups to cytosine bases—represents one of the best-characterized epigenetic mechanisms and plays crucial roles in transcriptional regulation, transposable element silencing, and genome stability [14]. In plants, DNA methylation occurs in symmetric (CG and CHG) and asymmetric (CHH) sequence contexts, each with distinct maintenance mechanisms [14].

In speed breeding environments, where plants experience constant optimized conditions rather than natural seasonal variations, epigenetic mechanisms may respond differently. The controlled environments of SB systems—with extended photoperiods, optimized temperatures, and sometimes elevated CO₂—could potentially induce epigenetic changes that affect trait expression and stability [14]. Understanding these epigenetic responses is essential for predicting trait performance when SB-developed lines are transferred to field conditions.

Epialleles and Their Potential in Crop Improvement

Epialleles are epigenetically modified variants of genes that produce altered expression patterns and corresponding phenotypic changes. Naturally occurring epialleles have been associated with agriculturally important traits in various crops. For example, in maize, epigenetic variations known as paramutations can affect pigment production and other characteristics [14]. Three classes of epigenetic variation have been defined:

- Obligatory epigenetic variation: completely dependent on DNA sequence change

- Facilitated epigenetic variation: caused by stochastic variation in epigenetic states

- Pure epigenetic variation: generated stochastically and completely independent of DNA sequence [14]

The stability and heritability of epialleles vary considerably, with some persisting for multiple generations while others are more transient. This variability presents both challenges and opportunities for crop improvement. Stable, heritable epialleles conditioning desirable agronomic traits could be selected for in breeding programs, while less stable epigenetic variation might be exploited for short-term adaptation [14].

Table 2: Types of Epigenetic Variation and Their Characteristics in Crop Plants

| Type of Variation | Dependence on DNA Sequence | Stability | Examples in Crops |

|---|---|---|---|

| Obligatory | Complete | High | FWA methylation in Arabidopsis dependent on tandem repeats |

| Facilitated | Partial | Variable | Hypomethylated mutants showing developmental abnormalities |

| Pure | Independent | Variable | Natural variation in DNA methylation between accessions |

Adapted from citation [14]

Integrated Protocols for Genetic and Epigenetic Analysis in Speed Breeding

Protocol 1: Accelerated Generation Advancement with Parallel Phenotyping

Objective: To rapidly advance plant generations while collecting high-quality phenotypic data for genetic and epigenetic studies.

Materials and Equipment:

- Controlled environment growth chambers with adjustable LED lighting

- Temperature and humidity control systems

- High-throughput phenotyping platforms (e.g., LemnaTec system)

- Tissue collection and preservation supplies

- DNA/RNA extraction kits

Methodology:

- Growth Conditions Setup: Implement extended photoperiods (20-22 hours light) with light spectra optimized for specific crops [10]. Maintain temperatures appropriate for the target species (typically 22-28°C during light periods, 18-22°C during dark periods).

- Population Management: Sow segregating populations in controlled environments. For each generation, harvest individual plants separately to maintain pedigree information.

- Tissue Sampling: Collect leaf tissue from each plant at designated developmental stages for DNA extraction. For epigenetic analysis, collect multiple tissue types (leaf, root, reproductive tissues) from representative plants.

- High-Throughput Phenotyping: Implement automated imaging systems (RGB, hyperspectral, fluorescence) to monitor growth, development, and stress responses throughout the lifecycle [18].

- Generation Advancement: For rapid cycling, employ techniques such as embryo rescue 14-20 days after flowering to overcome seed dormancy and reduce generation time [10].

- Data Integration: Correlate phenotypic data with genotypic and epigenotypic information to identify marker-trait associations.

Timeline: One generation of spring wheat or barley can be completed in approximately 8-9 weeks under optimized speed breeding conditions [10].

Protocol 2: Integrated Genetic-Epigenetic Analysis Pipeline

Objective: To simultaneously profile genetic and epigenetic variation in speed breeding populations and correlate with phenotypic data.

Materials and Equipment:

- Bisulfite conversion kits for DNA methylation analysis

- Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) or reduced-representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) platforms

- Genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) or SNP array platforms

- Bioinformatics computational resources

Methodology:

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Isolate high-quality genomic DNA from target tissues. For parallel transcriptome analysis, isolate RNA from matched samples.

- DNA Methylation Profiling:

- Perform bisulfite conversion of genomic DNA

- Conduct whole-genome bisulfite sequencing or targeted bisulfite sequencing

- Map sequencing reads to reference genome and call methylated cytosines in all sequence contexts (CG, CHG, CHH) [14]

- Genetic Variant Discovery:

- Perform whole-genome sequencing or genotyping-by-sequencing on the same DNA samples

- Identify SNPs, indels, and structural variants

- Integrated Analysis:

- Identify differentially methylated regions (DMRs) between genotypes or treatments

- Distinguish sequence-dependent and sequence-independent epigenetic variation

- Perform association analysis between epigenetic markers, genetic markers, and phenotypes

- Identify candidate epialleles contributing to trait variation

Timeline: From sample collection to integrated analysis, approximately 4-6 weeks depending on sequencing depth and sample number.

Diagram 1: Integrated Genetic-Epigenetic Analysis Workflow. This pipeline enables simultaneous profiling of genetic and epigenetic variation in speed breeding populations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Genetic-Epigenetic Studies in Speed Breeding

| Category | Specific Products/Platforms | Primary Function | Application in Speed Breeding |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Methylation Analysis | Bisulfite Conversion Kits | Chemical conversion of unmethylated cytosines to uracils | Identification of methylation patterns in speed-bred populations |

| Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) | Genome-wide methylation profiling at single-base resolution | Comprehensive epigenomic characterization | |

| Genetic Analysis | SNP Genotyping Arrays | High-throughput genotyping of known polymorphisms | MAS and genomic selection in accelerated breeding |

| Genotyping-by-Sequencing (GBS) | Discovery and genotyping of SNPs across populations | Genetic diversity monitoring in rapid generation cycles | |

| Phenotyping Platforms | LemnaTec Scanalyzer Systems | Automated, high-throughput plant phenotyping | Non-destructive trait monitoring in controlled environments |

| HyperART | Non-destructive quantification of leaf traits | Leaf chlorophyll content and disease severity assessment | |

| Bioinformatics Tools | BS-Seq Analysis Pipelines | Processing and interpretation of bisulfite sequencing data | Identification of DMRs in speed breeding conditions |

| AI/ML Algorithms for Phenotyping | Image analysis and pattern recognition | Automated trait extraction from high-throughput imaging |

Information compiled from multiple sources [14] [18] [19]

Speed breeding represents a paradigm shift in crop improvement, dramatically accelerating the breeding cycle while enabling integrated genetic and epigenetic analysis. The controlled environments of SB systems not only speed up generation turnover but also provide unique opportunities to study gene-environment interactions and epigenetic regulation under defined conditions. By combining SB with advanced genotyping, epigenotyping, and phenotyping technologies, researchers can dissect complex traits more efficiently and develop improved cultivars with enhanced yield, quality, and stress resilience. As these technologies continue to evolve, their integration promises to further accelerate crop improvement and contribute to global food security in the face of climate change and population growth.

With the global population projected to reach 10 billion by 2050, agricultural systems face unprecedented pressure to increase food production substantially [6] [13] [9]. This challenge is further exacerbated by climate change, which introduces new biotic and abiotic stresses that threaten crop yields worldwide [1] [20]. Conventional plant breeding methods, which typically require 8-15 years to develop new crop varieties, are insufficient to meet this accelerating demand [10] [13]. Speed breeding has emerged as a transformative approach that accelerates plant development and breeding cycles, enabling researchers to achieve in months what previously required years [9] [20].

Speed breeding utilizes controlled environment conditions to optimize plant growth and development, fundamentally compressing the time between generations [13]. Originally inspired by NASA experiments for space agriculture in the 1980s, the technique has evolved into a robust terrestrial application that manipulates key growth parameters including photoperiod, light quality, temperature, and planting density [11] [10]. By leveraging these controlled conditions, speed breeding can achieve 4-6 generations per year for many crucial crops, compared to the 1-2 generations possible with traditional field-based methods [11] [1]. This dramatic reduction in generation time represents a paradigm shift in plant breeding, offering a powerful tool to enhance genetic gain and rapidly deploy climate-resilient crops to safeguard global food systems [6] [3].

Theoretical Foundations: Physiological and Genetic Principles

The remarkable efficiency of speed breeding protocols rests upon manipulating fundamental physiological processes and genetic mechanisms that govern plant growth and development. Understanding these theoretical foundations enables researchers to optimize protocols for specific crops and environments.

Plant Physiology Under Controlled Conditions

At its core, speed breeding intervenes in key developmental stages of plants to reduce generation time [13]. The approach strategically manipulates several physiological processes:

Photoperiodism: Plants' physiological reaction to day/night length significantly influences flowering time. By extending photoperiods, speed breeding can promote continuous flowering in long-day plants and manipulate flowering responses in short-day species [11] [13]. For example, protocols for long-day crops like wheat and barley typically employ 22-hour photoperiods to hasten flowering, while short-day crops like rice and soybean require customized light regimes [3] [20].

Photosynthetic Efficiency: Extended light periods combined with optimized light spectra increase daily photosynthetic accumulation, driving faster biomass accumulation and development [11]. Research indicates that light spectra enriched with specific blue and red wavelengths significantly enhance photosynthetic efficiency compared to full-spectrum white light [9].

Hormonal Regulation: Light quality and quantity influence plant hormone production, including gibberellins and auxins that accelerate growth and flowering [11]. The precise manipulation of these hormonal pathways through environmental controls enables researchers to synchronize growth stages and compress life cycles.

Circadian Rhythms: Extended photoperiods modify plants' internal clocks, potentially triggering stress responses that must be carefully managed within speed breeding protocols [11]. Understanding species-specific circadian regulation is crucial for optimizing these accelerated growth conditions.

Genetic Considerations and Molecular Tools

Speed breeding interacts with several genetic mechanisms that influence breeding outcomes:

Flowering Time Genes: Genes such as FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) play crucial roles in determining flowering time under accelerated growth conditions [11]. Successful speed breeding protocols either leverage natural variation in these genes or manipulate their expression through environmental controls.

Vernalization Requirements: Some crops, particularly winter varieties, require a cold period to initiate flowering. Speed breeding protocols must either bypass these requirements through genetic selection or incorporate rapid vernalization techniques [11] [10].

Genetic Stability and Variation: An important consideration is whether accelerated growth conditions impact mutation rates or induce epigenetic changes that might affect genetic stability [11]. Research to date suggests that speed breeding produces genetically stable lines, though this remains an area of active investigation.

The integration of speed breeding with genomic technologies represents a particularly powerful synergy. When combined with marker-assisted selection, genomic selection, and gene editing, speed breeding transforms from merely a generation-acceleration tool into a comprehensive framework for rapid trait development and variety deployment [6] [13] [3].

Speed Breeding Methodologies: Protocols and Applications

The implementation of speed breeding requires careful attention to environmental parameters, species-specific requirements, and integration with modern breeding technologies. Below we outline core protocols and their applications across major crop species.

Core Speed Breeding Protocols

Table 1: Optimized Speed Breeding Protocols for Major Food Crops

| Crop Species | Photoperiod (Light:Dark) | Light Intensity (μmol m⁻² s⁻¹) | Temperature (°C) | Generations/Year | Key Protocol Adaptations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spring Wheat | 22:2 [11] | 400-600 [11] | 22/17 (day/night) [11] | 4-6 [11] [20] | Early seed harvest at 15-20% moisture [11] |

| Rice (Indica/Japonica) | Customized light recipes [3] | Not specified | Not specified | 4-5 [1] [20] | IRRI protocol enables flowering in 52-60 days [1] |

| Barley | 22:2 [11] | 400-600 [11] | 22/17 (day/night) [11] | ~6 [20] | Similar to wheat with high-density planting |

| Chickpea | 22:2 [11] | 400-600 [11] | 22/17 (day/night) [11] | ~6 [20] | Long-day promotion of flowering |

| Soybean | Short-day optimization [20] | Not specified | Not specified | ~5 [20] | Specific light quality adjustments for short-day flowering |

| Maize | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Combined with doubled haploid technology [1] |

Table 2: Speed Breeding 3.0 Framework Components (IRRI Protocol)

| Component | Key Technologies | Application | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| SpeedEdit | CRISPR-Cas9, Multiplex Genome Editing, Gene Drive [3] | Rapid trait stacking for climate-smart crops | Accelerated introduction of complex traits (e.g., C4 photosynthesis in rice) |

| SpeedScan | Machine Learning, Deep Learning, High-throughput Phenotyping [3] | Precision trait phenotyping | Reduced need for extensive field testing, ideotype development |

| SpeedWild | Customized flowering protocols for wild relatives [3] | Broadening genetic base of cultivated varieties | Introgression of valuable traits from wild species |

| SpeedAgri-tech | Controlled-environment agriculture, Vertical farming [3] | Space and indoor farming applications | Year-round production resilient to extreme weather |

| Chem-RGA | Chemical or hormonal treatments [3] | Rapid generation advancement in field conditions | Cost-effective acceleration without expensive infrastructure |

Experimental Setup and Workflow

A standardized speed breeding protocol involves several critical steps and environmental control parameters:

Growth Chamber Specifications: Temperature range 22°C ± 3°C, relative humidity 60-70%, CO₂ concentration 400-450 ppm [11]. These parameters maintain optimal growing conditions while preventing stress-induced growth inhibition.

Lighting Systems: Full-spectrum LED lighting with enhanced blue and red wavelengths, providing intensity of 400-600 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹ (PAR) [11] [9]. LED technology is preferred due to its energy efficiency, customizable spectra, and low heat emission [9].

Plant Growth Media and Nutrition: Soil mixture typically comprises 70% peat moss, 20% vermiculite, and 10% perlite, with pH adjusted to 6.0-6.5 [11]. Nutrient solutions such as modified Hoagland's solution with electrical conductivity of 1.5-2.0 mS/cm are applied through daily fertigation or automated drip systems [11].

Growth Management: The typical cycle includes vegetative phase (14-21 days), reproductive phase (28-35 days), and seed maturation (14-21 days) [11]. High-density planting at 100-150 plants/m² maximizes space utilization while maintaining individual plant health [11].

Integration with Modern Breeding Technologies

The true power of speed breeding emerges when integrated with contemporary biotechnological approaches:

Genomic Selection and Marker-Assisted Selection: Speed breeding rapidly advances generations while genomic technologies enable precise selection of desirable traits, dramatically increasing genetic gain per unit time [6] [13]. This combination has successfully developed herbicide-tolerant chickpea and disease-resistant rice varieties in significantly reduced timeframes [1] [20].

CRISPR-Cas9 and Genome Editing: The SpeedEdit component of Speed Breeding 3.0 seamlessly integrates speed breeding with advanced genome editing technologies [3]. This facilitates precise genetic modifications and trait stacking, such as combining multiple stress tolerances, while rapidly fixing these traits in breeding lines through accelerated generations.

High-Throughput Phenotyping: Automated imaging systems capture data on plant architecture, growth dynamics, and stress responses throughout the accelerated life cycle [18] [13]. When combined with machine learning and deep learning models, this enables prediction of trait performance in untested populations, significantly reducing the need for extensive field phenotyping [18] [3].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of speed breeding requires specific reagents and equipment to maintain precise environmental control and support rapid generation turnover.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Speed Breeding

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Application | Optimization Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Media Components | Peat moss, Vermiculite, Perlite [11] | Root zone aeration and moisture retention | pH 6.0-6.5; 70:20:10 ratio [11] |

| Nutrient Solutions | Modified Hoagland's solution [11] | Complete mineral nutrition | EC 1.5-2.0 mS/cm; daily fertigation [11] |

| Lighting Systems | Full-spectrum LED with enhanced blue/red [11] [9] | Optimized photosynthesis and photoperiod extension | 400-600 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹ PAR; 22h photoperiod [11] |

| Sterilization Agents | 1% sodium hypochlorite solution [11] | Surface sterilization of seeds | 24-48 hour pre-germination [11] |

| Plant Growth Regulators | Specific chemical/hormonal treatments [3] | Induce flowering and synchronize growth | Chem-RGA protocol for field conditions [3] |

| Phenotyping Tools | RGB cameras, Multispectral sensors [18] | High-throughput trait data collection | Automated imaging systems [18] |

Challenges and Implementation Considerations

Despite its significant promise, speed breeding faces several practical challenges that must be addressed for widespread adoption:

Infrastructure and Energy Costs: Maintaining controlled environments with extended photoperiods requires substantial energy input [1]. In regions with extreme climates, maintaining stable conditions demands constant operation of HVAC systems, leading to high electricity consumption [1]. Innovations in solar power, energy-efficient lighting, and automated climate control are being explored to mitigate these limitations [1].

Technical Expertise: Speed breeding facilities require regular maintenance and robust backup systems to avoid disruptions [1]. Technical staff need specialized training to operate and troubleshoot the complex environmental control systems, which may present barriers in resource-limited settings [1].

Crop-Specific Optimization: Protocols must be carefully adjusted for different species and even varieties within species [13]. Short-day crops like rice and soybean require different lighting regimes than long-day species like wheat and barley [20]. Furthermore, optimal conditions can vary among genotypes within a species, necessitating preliminary optimization experiments.

Validation and Correlation with Field Performance: A critical consideration is whether traits expressed under speed breeding conditions correlate with field performance [10]. Research indicates that speed breeding environments are highly effective for phenotyping stable traits, with indoor evaluations accurately reflecting field performance for many characteristics [3]. However, genotype × environment interactions must be carefully evaluated through multi-location trials.

Speed breeding represents a transformative approach to crop improvement that directly addresses the urgent need to enhance global food security for a projected population of 10 billion by 2050. By enabling rapid generation advancement, this technology dramatically shortens breeding cycles from years to months, allowing breeders to respond with unprecedented agility to emerging challenges such as climate change, novel pathogens, and evolving consumer demands [6] [3].

The future of speed breeding lies in its continued integration with complementary technologies. As protocols become more refined and accessible, and as costs decrease with technological advancements, speed breeding is poised to become a standard component of public and private breeding programs worldwide [1] [20]. The democratization of these techniques through initiatives like IRRI's consortium for National Agricultural Research and Extension Systems (NARES) ensures that benefits extend beyond well-funded institutions to breeding programs in developing nations where food security challenges are most acute [3].

Looking forward, the evolution from initial speed breeding protocols to comprehensive frameworks like Speed Breeding 3.0 signals a shift from mere acceleration to a fundamental reimagining of plant breeding as a predictive, precise, and proactive discipline [3]. By transforming breeding from a reactive process into an anticipatory strategy, speed breeding offers a powerful solution to align agricultural innovation with the accelerating pace of environmental change, ultimately contributing to more resilient and productive global food systems capable of nourishing a growing population.

Speed Breeding in Practice: Protocols, System Setup, and Integration with Modern Technologies

Speed breeding represents a transformative innovation in modern crop improvement, leveraging precise control of core environmental components to drastically accelerate plant growth and development cycles. This technology addresses a critical bottleneck in traditional plant breeding—the lengthy generation time—by enabling researchers to achieve 4 to 6 generations of many crop species annually rather than the typical 1–2 generations possible in field conditions [13] [21]. The foundational principle involves the integrated optimization of photoperiod, light spectra, temperature, and CO₂ levels to create controlled environments that promote rapid flowering and seed set [13] [22]. This protocol details the specific application notes and experimental methodologies for implementing these core system components within the context of a comprehensive thesis on speed breeding techniques for crop improvement research.

Core Component Optimization and Quantitative Parameters

The synergistic management of environmental factors is crucial for successful speed breeding. The following sections and corresponding tables summarize optimized parameters for diverse crop species.

Photoperiod Management Strategies

Photoperiod management is fundamental for triggering developmental phase transitions, particularly the shift from vegetative to reproductive growth [21]. Optimization requires species-specific approaches:

- Long-day plants (LDP) such as wheat, barley, and chickpea typically flower most rapidly under extended photoperiods of 20–22 hours [13] [21].

- Short-day plants (SDP) including soybean, rice, and amaranth require shorter light periods (8–13 hours) to induce flowering [23] [24]. For SDP, some protocols recommend dynamic adjustment, implementing longer photoperiods (e.g., 13 hours) during vegetative stages to promote biomass accumulation, then switching to shorter photoperiods (e.g., 8 hours) to trigger flowering [13] [24].

Table 1: Optimized Photoperiod and Spectral Parameters for Various Crops

| Crop Species | Photoperiod (Light/Dark) | Recommended Light Spectrum | Light Intensity (µmol m⁻² s⁻¹) | Generations/Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spring Wheat | 22 h / 2 h [21] | Full spectrum LED [11] | 400–600 [11] | 4–6 [21] |

| Soybean (SDP) | 10 h / 14 h [23] or 8 h / 16 h [25] | Red-White LED [25] or Blue-light enriched, Far-red deprived [23] | 513 [25] | Up to 5 [23] |

| Rice (SDP) | 13 h / 11 h (Vegetative), 8 h / 16 h (Reproductive) [24] | Cost-effective Halogen tubes [24] | ~750–800 [24] | 4–5 [24] |

| Amaranth (SDP) | 10 h / 14 h [23] | Near-red light recipe [23] | 574 [23] | Up to 5 [23] |

Light Spectrum and Quality Optimization

Light-emitting diodes (LEDs) provide unparalleled control over light quality, allowing researchers to fine-tune spectral composition for specific physiological outcomes [26] [23].

- Blue Light (400–500 nm): Regulates stomatal opening, phototropism, and inhibition of stem elongation. It is crucial for maintaining compact, sturdy plant architecture [23].

- Red Light (600–700 nm): Strongly drives photosynthesis and influences flowering time via the phytochrome system [22].

- Far-Red Light (700–800 nm): Can promote shade avoidance responses and stem elongation. Its effect on flowering time is species-specific; it accelerates flowering in some rice and amaranth genotypes but has no effect in soybeans [23].

Research demonstrates that a Red-White (RW) LED spectrum significantly reduces time to flowering and maturity in soybeans compared to Blue (BL) LED light [25]. For short-day crops, a blue-light enriched, far-red-deprived spectrum under a 10-hour photoperiod promotes early flowering and compact growth [23].

Temperature and CO₂ Regulation

Precise temperature control is vital for maximizing metabolic efficiency and coordinating development with light regimes.

- Most speed breeding protocols maintain temperatures between 22–28°C, with minimal day/night variation to avoid developmental delays [11].

- Elevated CO₂ (eCO₂) concentrations (~550–700 ppm) enhance photosynthetic rates, biomass accumulation, and yield, particularly in C3 plants like wheat and fababean [27] [21]. CO₂ supplementation is a key feature of advanced "Speed Breeding 3.0" protocols, helping to offset potential trade-offs from accelerated growth [26].

Table 2: Optimized Temperature and CO₂ Parameters for Controlled Environments

| Environmental Factor | Optimal Range | Experimental Example & Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 22–28°C [11] | 28°C day/night for soybean, rice, and amaranth resulted in maturity within 77 days [23]. |

| CO₂ Concentration | 400–700 ppm [21] | Elevated CO₂ (eCO₂ at 550 ppm day/610 ppm night) significantly enhanced growth and yield of intercropped fababean and wheat [27]. |

| Relative Humidity | 60–70% [11] | Prevents desiccation stress under intense lighting and supports normal physiological function. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Systems

Protocol 1: LED-Based Speed Breeding for Short-Day Crops

This protocol, adapted from Jähne et al. (2020), is designed for soybean, rice, and amaranth [23].

Application Notes: This system enables up to five generations per year of short-day crops using crop-specific LED lighting regimes without tissue culture. It is ideal for rapid generation advancement via the single seed descent (rSSD) method.

Materials & Reagents:

- Plant material: Seeds of target SDP species.

- Growth chambers with precise temperature and humidity control.

- Tunable LED light systems capable of specific spectral recipes.

- Pots (7 cm × 7 cm × 8 cm) or 96-cell plates for high-density planting.

- Appropriate soil substrate.

Methodology:

- Environmental Setup: Program the growth chamber to a constant temperature of 28°C and high relative humidity (80–100%).

- Light Regime: Set a 10-hour photoperiod. Use a light spectrum that is blue-light enriched and far-red deprived.

- Cultivation: Sow pre-germinated seeds in pots or multi-cell trays. For soybeans, inoculate the substrate with appropriate rhizobia.

- Watering and Nutrition: Implement automated sub-irrigation systems. Adjust nutrient delivery according to developmental stage.

- Phenotyping and Harvest: Monitor days to flowering daily. Cessation of watering 5 days before harvest accelerates seed ripening. Harvest seeds approximately 70 days after sowing for soybeans.

Protocol 2: A Cost-Effective Speed Breeding System for Rice ("SpeedyPaddy")

This protocol provides a resource-conscious option for large-scale rice germplasm advancement [24].

Application Notes: The "SpeedyPaddy" system reduces the breeding cycle to 68–75 days, enabling 4–5 generations per year across different rice varieties. It is highly suitable for integration with genomics-assisted selection and trait phenotyping.

Materials & Reagents:

- Infrastructure: Modified screenhouse with basic climate control.

- Lighting: Halogen tubes (500-watts) providing a light intensity of ~750–800 µmol m⁻² s⁻¹.

- Temperature Control: Coiled heaters for maintaining night temperatures.

- Growing System: 98-well plug trays for high-density planting (700 plants/m²).

Methodology:

- Photoperiod Management: Implement a dynamic light regime: 13h light/11h dark during seedling and vegetative stages, switching to 8h light/16h dark to induce reproductive development.

- Temperature Control: Maintain 30–32°C during light hours and 23–25°C during dark hours using coiled heaters.

- Nutrient Management: Apply a balanced nutrient solution at specific growth stages, as over-fertilization can be detrimental in high-density plantings.

- Seed Harvest: Conduct early seed harvest 12–15 days after flowering to shorten the generation cycle, followed by rapid drying.

Molecular Physiology and Signaling Pathways

The physiological outcomes of speed breeding are governed by internal signaling pathways that respond to optimized environmental cues.

Pathway Integration and Application:

- The Photoperiod Pathway is activated by extended light exposure and specific light spectra, leading to the expression of florigen genes like FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT), which initiates flowering [22].

- The Vernalization and Gibberellin Pathways are modulated by temperature. In some crops, elevated temperatures can mimic vernalization requirements, while gibberellin levels influence stem elongation and flowering vigor [22].

- Elevated CO₂ enhances photosynthetic carbon fixation, providing increased energy and carbon skeletons that feed into the Autonomous Pathway, supporting the resource-intensive process of accelerated flower and seed development [27].

- These pathways converge to trigger the final outcome of accelerated flowering and seed set, which is the core objective of speed breeding.

Experimental Workflow and System Integration

Implementing a successful speed breeding program requires a methodical approach from initial setup to data collection.

This workflow highlights the iterative nature of speed breeding, where each completed cycle informs the next, enabling rapid trait fixation and line development.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of the above protocols requires specific materials and reagents. The following table catalogs key solutions for establishing a speed breeding research program.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Speed Breeding

| Item Category | Specific Examples / Models | Primary Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Lighting Systems | Tunable LED Panels (e.g., Ecotune, Relumity) [23]; Cost-effective Halogen Tubes [24] | Providing precise photoperiod control and customizable light spectra (Blue, Red, White, Far-Red) to manipulate plant growth and flowering. |

| Growth Chambers | Walk-in rooms or enclosed "Speed Breeding Boxes" with reflecting surfaces [23] | Maintaining strict control over temperature, humidity, and CO₂ levels, independent of external environmental fluctuations. |

| Soil & Substrate | Peat moss, vermiculite, perlite mixtures [11]; Sand & nutrient soil blends [25] | Providing physical support and optimized water/nutrient holding capacity for healthy root development under accelerated growth. |

| Nutrient Solutions | Modified Hoagland’s Solution [11]; Balanced 15-15-15 (N-P-K) fertilizer [25] | Delivering essential macro and micronutrients to support rapid plant growth and development in a high-density planting system. |

| Phenotyping Tools | Portable leaf area meters; PAR meters; DNA extraction kits for genotyping | Quantifying growth parameters, light intensity at canopy level, and facilitating marker-assisted selection for trait introgression. |

The precise and integrated control of photoperiod, light spectra, temperature, and CO₂ concentration forms the operational backbone of any successful speed breeding system. The protocols and application notes detailed herein provide a scientifically-grounded framework for researchers to accelerate crop improvement cycles significantly. By adopting these optimized parameters and methodologies, breeding programs can enhance their rate of genetic gain, rapidly develop climate-resilient cultivars, and contribute more effectively to global food security. Future advancements will likely focus on further refining these environmental interactions, reducing operational costs, and integrating speed breeding with next-generation technologies like genomic selection and gene editing [26].

Speed breeding (SB) represents a transformative approach in modern plant breeding, designed to significantly accelerate the generation turnover of crops through the precise manipulation of environmental conditions [10]. By optimizing factors such as photoperiod, light intensity, light quality, temperature, and humidity, SB induces physiological changes that promote faster flowering and maturation, thereby reducing the breeding cycle time [5]. This methodology has evolved from initial experiments with artificial lighting over a century ago to sophisticated, light-driven protocols known as Speed Breeding 3.0, which integrate advanced genomic tools for sustainable genetic gains [26]. The core principle involves creating controlled environments that minimize the vegetative period of each generation by accelerating flowering, enabling rapid seed maturation, and overcoming postharvest dormancy to permit successive cultivation cycles [10].

The application of SB varies significantly between long-day (LD) and short-day (SD) plant species, necessitating distinct protocols for each photoperiodic category. LD crops, such as wheat and barley, flower most rapidly when exposed to extended photoperiods exceeding 16 hours, while SD crops, including rice and finger millet, require shorter light periods to induce flowering [28] [5]. This article provides detailed, step-by-step SB protocols for major crops in both categories, framed within the context of crop improvement research, to enable researchers and scientists to implement these techniques effectively in their breeding programs.

Comparative Analysis of Speed Breeding Protocols

Table 1: Comparative Speed Breeding Protocols for Major Long-Day Crops

| Crop Species | Photoperiod (Light/Dark) | Temperature (°C) | Light Intensity (μmol m⁻² s⁻¹) | Key Technical Interventions | Generations Per Year | Seed-to-Seed Cycle (Days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat (Spring) | 22h/2h [28] | 22-25°C [28] | 450-500 [29] | Early harvest at 14-21 DAF [29] | 4-6 [10] | ~77 [2] |

| Wheat (Winter) | 22h/2h [28] | 25/22 (day/night) [28] | Not specified | Vernalization requirement management [28] | 4 [28] | Reduced by 30 days/cycle [28] |

| Barley | 22h/2h [29] | 22/16 (day/night) [29] | 450-500 [29] | Early harvest at 21 DAF [29] | 6 [29] | 88 [29] |

| Oats | 22h/2h [28] | 22°C [28] | Not specified | Early panicle harvest [28] | 5 [28] | Not specified |

| Canola/Rapeseed | 22h/2h [10] | 20-25°C [10] | Not specified | Not specified | 4 [10] | Not specified |

Table 2: Comparative Speed Breeding Protocols for Major Short-Day Crops

| Crop Species | Photoperiod (Light/Dark) | Temperature (°C) | Light Intensity (μmol m⁻² s⁻¹) | Key Technical Interventions | Generations Per Year | Seed-to-Seed Cycle (Days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice (Indica/Japonica) | 10h [28] or continuous light followed by reduced light [28] | Not specified | Not specified | Blue light enriched far blue spectrum; embryo rescue [28] | 4-6 [28] [1] | 52-60 to flowering [1] |

| Finger Millet | 9h [5] | 29±2 [5] | Not specified | High-density planting (105 plants/1.5 sq.ft.); restricted irrigation [5] | 4-5 [5] | Reduced by 28-54 days [5] |

| Soybean | 10h [10] | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified |

| Cotton | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified |

| Sorghum | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified |

Detailed Protocols for Long-Day Species

Wheat Speed Breeding Protocol

The wheat SB protocol enables the production of 4-6 generations per year, dramatically reducing the traditional breeding timeline [10]. The following methodology is adapted from established protocols for both spring and winter wheat varieties.

Growth Conditions and Facility Setup: Maintain a photoperiod of 22 hours light and 2 hours darkness using full-spectrum LED lights [28]. For spring wheat, maintain a constant temperature of 22-25°C, while for winter wheat, implement a day temperature of 25°C and night temperature of 22°C to manage vernalization requirements [28]. Light intensity should be maintained at 450-500 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹ [29]. For winter wheat varieties with vernalization requirements, expose germinated seeds to cold treatment (2-4°C) for 4-8 weeks before transferring to SB conditions [28].

Planting and Cultivation Management: Utilize high-density planting with approximately 1000 plants/m² in 50-cell trays to optimize space utilization [28] [2]. Use a well-draining soil mixture composed of soil, sand, and vermicompost in a 3:2:1 ratio [5]. Apply controlled-release fertilizer with NPK composition of 15:9:12 at the four-leaf stage, supplemented with 0.2% NPK (19:19:19) if leaves exhibit pale green coloration [5] [29]. Implement automated irrigation systems such as ebb-and-flow for 5-6 minutes every alternate day to maintain consistent moisture levels [5].

Early Harvest and Seed Processing: Monitor flowering time closely and harvest spikes 14-21 days after flowering (DAF) for spring wheat, when embryos are fully developed but seeds are not yet physiologically mature [29]. Immediately after harvest, dry spikes in air-tight containers with silica gel at 15°C for 5 days to preserve viability and overcome dormancy [29]. Hand-thresh seeds and store at 4°C for 4 days to homogenize dormancy effects before initiating the next generation [29]. For seeds with strong dormancy, apply hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) treatment at reduced temperature to break dormancy [28].

Barley Speed Breeding Protocol

The barley SB protocol enables completion of a full generation in approximately 88 days, representing a 20% reduction compared to normal breeding systems [29].

Growth Conditions and Facility Setup: Implement a 22-hour photoperiod with 2 hours of darkness using high-intensity top-light white lamps [29]. Maintain day temperature at 22°C and night temperature at 16°C with light intensity between 450-500 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹ [29]. Relative humidity should be controlled at 70% to optimize plant development and minimize disease pressure [5].

Planting and Cultivation Management: Plant seeds in PRO-MIX planting media or similar well-draining substrate [29]. At the three-leaf stage, thin to one plant per pot to minimize competition. Apply Osmocote Smart-Release Plant Food Plus (25 g per plot) at the four-leaf stage, with composition of 15% nitrogen, 9% available phosphate, 12% soluble potash, and essential micronutrients [29]. Water daily and use stakes to prevent lodging as plants mature [29].