Plant Secondary Metabolites in Defense: Molecular Mechanisms, Biotechnological Applications, and Drug Discovery

This comprehensive review synthesizes current knowledge on the role of plant secondary metabolites (SMs) in defense mechanisms, addressing the critical needs of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Plant Secondary Metabolites in Defense: Molecular Mechanisms, Biotechnological Applications, and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This comprehensive review synthesizes current knowledge on the role of plant secondary metabolites (SMs) in defense mechanisms, addressing the critical needs of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational biology of major SM classes—including alkaloids, terpenoids, phenolics, and saponins—and their specific molecular actions against pathogens and herbivores. The article details advanced methodological approaches for SM characterization and biotechnological application, examines current challenges in metabolic engineering and sustainable production, and provides comparative analyses of SM efficacy against drug-resistant pathogens. By integrating recent advances in omics technologies, genetic engineering, and synthetic biology, this work establishes a robust framework for harnessing plant SMs in developing novel therapeutics and sustainable agricultural solutions to address pressing global challenges in medicine and food security.

The Chemical Arsenal: Foundational Classes and Defense Mechanisms of Plant Secondary Metabolites

Plant metabolism is a complex network of biochemical pathways broadly divided into the production of primary and secondary metabolites, each fulfilling distinct physiological roles. Primary metabolites are universal compounds essential for fundamental life processes such as growth, development, and reproduction; they are present across all plant species and include molecules like carbohydrates, lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids [1] [2]. In contrast, secondary metabolites (SMs) are organic compounds that are not essential for basic cellular processes but are indispensable for a plant's ecological interactions and survivability [1] [3] [2]. Their production is often restricted to specific plant lineages or even species, and they are synthesized from the intermediates or end products of primary metabolism [3] [4]. The term "secondary metabolite" was first coined by Albrecht Kossel, the 1910 Nobel Prize laureate, and was later described by Friedrich Czapek as end products of nitrogen metabolism [3]. While the absence of SMs does not result in immediate cell death, it can severely compromise the plant's long-term fitness and adaptive capabilities in its environment [2].

Table 1: Core Distinctions Between Primary and Secondary Metabolites

| Feature | Primary Metabolites | Secondary Metabolites |

|---|---|---|

| Physiological Role | Essential for growth, development, and reproduction [1] [2] | Essential for defense and ecological interactions [1] [3] |

| Distribution | Universal in all plant species [1] | Restricted to specific lineages or species [1] [3] |

| Chemical Diversity | Limited (e.g., sugars, amino acids, common organic acids) [2] | Vast (Over 200,000 identified compounds) [4] |

| Production Phase | Produced during the active growth phase (trophophase) [2] | Often produced during stationary or stress-induced phases [5] |

| Function in Plants | Directly involved in metabolism, structure, and energy storage [1] | Defense against herbivores, pathogens, and abiotic stress; attractants for pollinators [1] [4] |

| Examples | Sucrose, cellulose, chlorophyll, DNA [1] | Morphine, caffeine, lignin, taxol [1] [3] |

Biosynthetic Origins and Major Chemical Classes

The biosynthesis of secondary metabolites is intricately linked to primary metabolic pathways, which provide the necessary building blocks and energy. Three core primary pathways serve as the foundation for SM diversity: the shikimic acid pathway, responsible for generating aromatic amino acids and phenolic compounds; the mevalonic acid (MVA) and methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathways, which produce terpenoid precursors; and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, which contributes to the synthesis of various organic acids [4] [2]. These pathways are highly responsive to environmental stress, leading to the production of protective SMs [4]. The resulting SMs are classified into three major groups based on their biosynthetic origin and chemical structure: terpenoids, phenolics, and nitrogen-containing compounds (e.g., alkaloids) [3] [4] [2].

Table 2: Major Classes of Plant Secondary Metabolites and Their Origins

| Class | Biosynthetic Precursor/Pathway | Key Sub-Classes & Examples | Primary Ecological Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Terpenoids | Acetyl CoA, Intermediates of Glycolysis; MVA & MEP pathways [1] [4] | Monoterpenes (Menthol, Pyrethroids), Diterpenes (Paclitaxel), Triterpenoids (Phytoecdysones), Tetraterpenoids (Beta-carotene) [1] [3] | Insect repellent, insecticide, inhibition of cell division in herbivores, disrupt insect molting, attract pollinators [1] |

| Phenolic Compounds | Amino Acid Phenylalanine; Shikimic Acid Pathway [1] [4] | Simple Phenolics (Salicylic acid), Flavonoids (Anthocyanins, Resveratrol), Lignin [1] [3] [4] | Antioxidant, structural support (wood), defense against fungi, pigmentation to attract pollinators [1] [3] |

| Alkaloids | Amino Acids (e.g., Tryptophan, Tyrosine); Shikimic Acid & TCA pathways [1] [2] | Morphine, Codeine, Cocaine, Quinine, Caffeine, Nicotine, Atropine [1] [3] | Potent toxin and feeding deterrent against herbivores; bitter taste [1] |

| Nitrogen- & Sulfur-Containing Compounds | Various Amino Acids [4] | Glucosinolates (Glucoraphanin), Cyanogenic Glycosides, Thionine, Phytoalexins [4] [2] | Deterrent against herbivores and pathogens; counteract oxidative stress [4] |

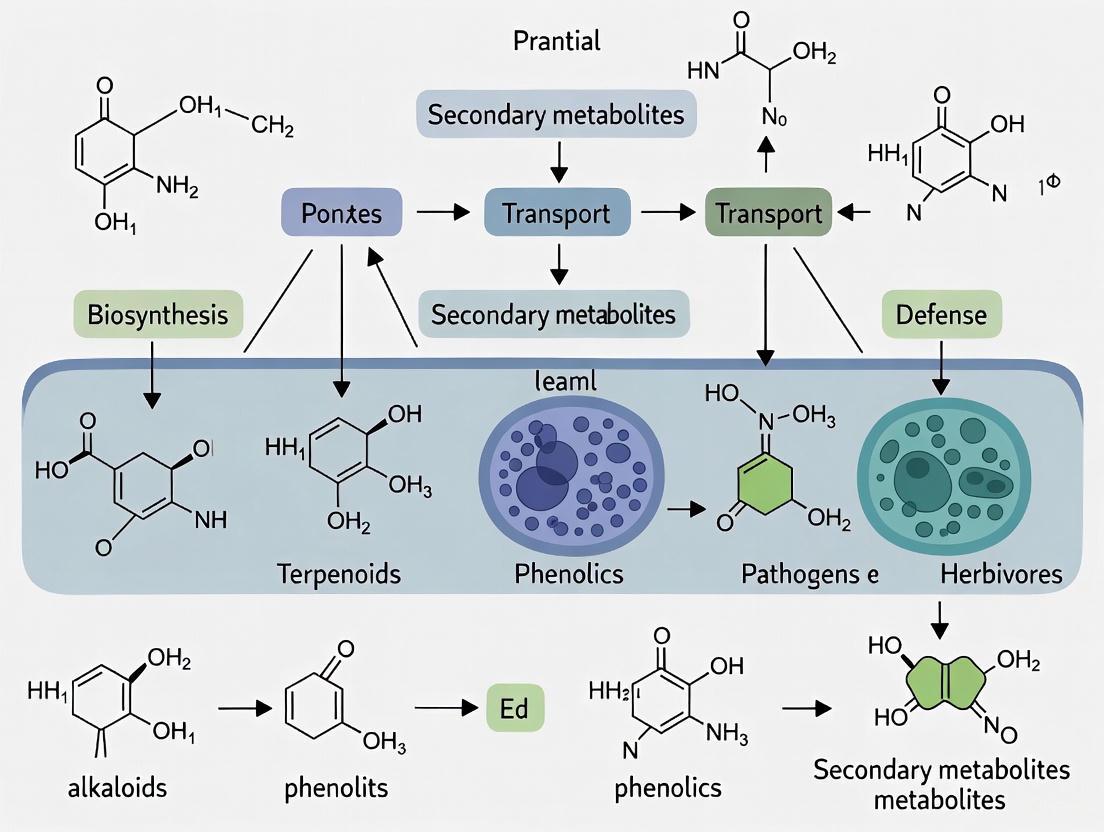

Diagram 1: SM biosynthetic pathways and primary metabolism integration.

Central Regulatory Role in Plant Defense

Defense Against Biotic Stressors

Plants employ secondary metabolites as central regulators in a continuous evolutionary "arms race" with herbivores and pathogens [4]. This co-evolutionary dynamic drives the development of sophisticated defense mechanisms. SMs function as direct defenses by acting as toxins, antifeedants, or antibiotics, and as indirect defenses by facilitating the recruitment of natural enemies of herbivores [4].

- Alkaloids: These nitrogen-containing compounds are potent toxins and feeding deterrents [1]. For example, the alkaloid senecionine in groundsel plants causes liver failure and fatalities in livestock [1]. Their mode of action often involves interfering with animal nervous systems, acting as nerve poisons, enzyme inhibitors, or membrane transport inhibitors [1]. Furthermore, many alkaloids have a bitter taste, which animals learn to associate with negative effects, thus developing avoidance behaviors [1].

- Terpenoids: This highly diverse class plays multiple defensive roles. Monoterpenes, such as the aromatic oils in mint, function as insect repellents [1]. Pyrethroids, derived from chrysanthemums, are commercially used as insecticides due to their neurotoxic effects on insects and low mammalian toxicity [1]. Another strategy involves triterpenoids like phytoecdysones, which mimic insect molting hormones; when ingested in excess, they disrupt the normal molting cycle, leading to lethal consequences for the insect [1].

- Phenolic Compounds: Phenolics offer both structural and chemical defense. Lignin, a complex phenolic polymer, is a main component of wood. It strengthens cell walls, making plant tissues less palatable and more difficult to digest for insects and fungal pathogens [1]. Simpler phenolics, such as salicylic acid, are crucial in activating a plant's complex defense response against fungal pathogens [1]. Isoflavones in legumes are rapidly synthesized upon pathogen attack and exhibit strong antimicrobial activity [1].

Mitigation of Abiotic Stresses

Beyond biotic interactions, SMs are crucial for plant adaptation and resilience to abiotic stresses such as drought, salinity, heavy metals, and UV radiation [4]. These stresses disrupt physiological processes, but SMs help mitigate the damage.

- Antioxidant Activity: Many abiotic stresses induce the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that can damage cellular components. Phenolic compounds like flavonoids, stilbenes (e.g., resveratrol), and curcuminoids are powerful antioxidants that neutralize ROS, protecting nucleic acids and proteins from oxidative damage [4].

- Structural Protection: Lignin and suberin (a complex polymer derived from phenolics) are deposited in cell walls, forming barriers that reduce water loss and prevent the entry of toxic ions under drought and salinity stress [4].

- UV Protection: Phenylpropanoids and other phenolic compounds absorb harmful UV radiation, thereby protecting plant tissues from UV damage [3].

Experimental Protocols for SM Analysis

The qualitative and quantitative analysis of SMs requires a systematic approach, from sample preparation to data interpretation. The following protocol, adapted from research on Paulownia species, outlines a standard workflow for isolating and characterizing SMs from plant tissue [6].

Sample Preparation and Extraction

- Plant Material Collection: Collect the desired plant organs (e.g., leaves, twigs, flowers, fruits). The study on Paulownia Clon in Vitro 112 showed that the type and quantity of SMs can vary significantly between different morphological parts of the plant [6].

- Lyophilization: Freeze-dry the plant material to preserve labile compounds and facilitate grinding.

- Homogenization: Grind the dried material into a fine powder using a mortar and pestle or a mechanical grinder.

- Solvent Extraction: Extract metabolites from the powdered tissue using a series of solvents of increasing polarity (e.g., hexane, chloroform, ethyl acetate, methanol, water) in a Soxhlet apparatus or via maceration. This step separates compounds based on their solubility.

Compound Isolation and Purification

- Liquid-Liquid Partitioning: Separate the crude extract into fractions containing compounds of different polarities.

- Chromatographic Techniques:

- Column Chromatography (CC): Use silica gel or other stationary phases for initial fractionation of the extract.

- Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC): Monitor the separation process and identify fractions of interest.

- High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC): Further purify individual compounds from the complex fractions. This is a high-resolution method essential for obtaining pure SMs.

Structural Elucidation and Quantification

- Spectroscopic Analysis:

- Mass Spectrometry (MS): Determine the molecular weight and fragmentation pattern of the purified compound. Techniques like GC-MS or LC-MS are commonly used [6] [5].

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: Analyze the structure of the compound. The chemical structure of isolated compounds is confirmed using spectral methods like 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR [6].

- Quantitative Analysis: Develop and validate an analytical method (e.g., using HPLC with a UV or MS detector) to determine the precise concentration of individual SMs in different plant parts [6].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for plant secondary metabolite analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for SM Research

| Item/Category | Function in Research | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Solvents for Extraction | To dissolve and extract metabolites from plant matrix based on polarity. | n-Hexane (non-polar lipids), Chloroform (medium polarity compounds), Ethyl Acetate, Methanol (polar compounds like flavonoids), Water (highly polar glycosides) [6] |

| Chromatography Media | To separate complex mixtures into individual compounds. | Silica Gel (for open column and TLC), C18-bonded silica (for reverse-phase HPLC), Sephadex LH-20 (for size exclusion of natural products) [6] |

| Spectroscopy Standards | To calibrate instruments and provide reference data for compound identification. | Deuterated Solvents (for NMR, e.g., CDCl3, DMSO-d6), Internal Standards (for quantitative MS, e.g., stable isotope-labeled compounds) [6] |

| Elicitors | To induce or enhance the production of SMs in plant cell or tissue cultures for study. | Jasmonic Acid, Salicylic Acid, Chitin Oligosaccharides (mimic pathogen attack); Metal Ions, UV Light (simulate abiotic stress) [4] [2] |

| Enzymes & Molecular Biology Kits | To study biosynthetic pathways and genetic regulation of SM production. | RNA/DNA Extraction Kits, Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Reagents, Reverse Transcriptase for gene expression analysis of biosynthetic genes [4] |

The profound biological activities of plant secondary metabolites have made them an invaluable resource in drug discovery and pharmaceutical development [1] [3] [2]. Many SMs are used directly as medicines or serve as lead compounds for the semi-synthesis of more potent drugs.

- Alkaloids: Morphine and codeine from the opium poppy are cornerstone analgesics [1] [3]. Vincristine and vinblastine from the rosy periwinkle are critical chemotherapeutic agents used to treat blood and lymphatic cancers [1] [3]. Quinine from cinchona bark was the primary antimalarial drug for centuries [1].

- Terpenoids: Paclitaxel (Taxol), a diterpene from the Pacific yew tree, is a potent inhibitor of cell division and is used to treat ovarian, breast, and lung cancers [1] [3]. Artemisinin, a sesquiterpene from Artemisia annua, is a powerful antimalarial for which its discoverer, Tu Youyou, was awarded a Nobel Prize [3].

- Phenolic Compounds: Digoxin, a cardiac glycoside from foxglove, is used to treat heart conditions like atrial fibrillation and heart failure [3]. The simple phenolic salicylic acid, derived from willow bark, is the precursor to aspirin [1].

In conclusion, plant secondary metabolites, while distinct from primary metabolites in their role in the producing plant, are central to plant survival through their multifaceted defense functions. Their intricate biosynthetic pathways and potent biological activities not only shape ecological interactions but also provide a rich and ongoing source of inspiration for pharmaceutical innovation. The continued study of these compounds, leveraging advanced analytical and molecular techniques, is essential for unlocking new therapeutic agents and enhancing crop resilience in a changing global climate.

Secondary metabolites are organic compounds that are not directly involved in the normal growth, development, or reproduction of plants but are essential for their survival and ecological interactions. These compounds serve as central regulators of plant defense against a wide range of biotic and abiotic stresses [7]. In the continuous co-evolutionary arms race between plants and their stressors, secondary metabolites have emerged as sophisticated chemical weapons and signaling molecules that deter herbivores, prevent pathogen infections, alleviate oxidative damage, and facilitate communication with beneficial organisms [7]. The four major classes—alkaloids, terpenoids, phenolics, and glycosides—represent distinct biochemical strategies that plants have developed to adapt to their environments and ensure their survival. Understanding the structural diversity, biosynthetic pathways, and ecological functions of these compounds provides valuable insights for developing sustainable agricultural practices and discovering novel pharmaceutical agents.

Alkaloids

Structural Diversity and Biosynthesis

Alkaloids represent one of the largest classes of plant specialized metabolites, characterized by the presence of at least one nitrogen atom, typically within a heterocyclic structure. To date, over 20,000 different alkaloids have been identified across various plant species [8]. This extensive class is broadly categorized into "true alkaloids" and "pseudoalkaloids" based on the origin of their nitrogen. True alkaloids, such as nicotine, camalexin, and benzoxazinoids (BXs), contain nitrogen within a heterocyclic structure derived from amino acids. In contrast, pseudoalkaloids are synthesized from non-amino acid precursors and include terpene-like, steroid-like, and purine-like alkaloids, such as aconitine, tomatine, and caffeine, respectively [8].

Alkaloids are the primary bioactive compounds in many valuable medicinal plants with notable pharmacological activities. Examples include leonurin from Leonurus species, dendrobine from Dendrobium nobile, ephedrine from Ephedra sinica, triptolide from Tripterygium wilfordii, and scopolamine from Datura metel L. These alkaloids exhibit diverse pharmacological properties, including neuroprotection, antitumor activity, anti-inflammatory effects, antibacterial action, and antiviral capabilities [9].

Defense Mechanisms and Ecological Roles

Alkaloids serve as essential defensive compounds for plants, playing a critical role in their survival and reproduction by resisting insect infestations and attracting pollinators [9]. Known for their potent bioactivities, these metabolites have primarily been described in the context of aboveground defense against pathogens, insects, and herbivores [8]. For example, nicotine is among the most well-characterized toxic alkaloids produced by plants in the genus Nicotiana, which deters a wide range of insect herbivores by targeting acetylcholine receptors in the animal nervous systems [8].

Beyond these defensive functions, recent studies have revealed that alkaloids also mediate interactions between plants and their associated root microbiota. These interkingdom metabolic interactions improve plant fitness, particularly under changing environmental conditions [8]. Plants secrete measurable amounts of alkaloids as root exudates into the rhizosphere, with secretion levels varying across different growth stages and influenced by soil nutritional conditions [8].

Table 1: Representative Defensive Alkaloids and Their Functions

| Alkaloid Name | Plant Source | Primary Defense Function | Additional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nicotine | Nicotiana species | Insecticidal, targets nervous system | Basis for synthetic neonicotinoids |

| Tomatine | Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) | Antimicrobial, defense against pathogens | Secreted in root exudates |

| Camalexin | Arabidopsis thaliana | Phytoalexin, defense against pathogens | Induced by pattern-triggered immunity |

| Monocrotaline | Crotalaria species (Fabaceae) | Defense against herbivores | Nodule-specific biosynthesis induced by rhizobia |

| Benzoxazinoids | Maize, wheat | Defense against aboveground herbivores | Metabolized by root microbiota |

Experimental Analysis Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantification of Alkaloid Secretion in Root Exudates

- Plant Growth and Collection: Grow plants under controlled conditions using a hydroponic culture system. Collect root exudates at different growth stages by immersing roots in sterile distilled water for a defined period (e.g., 2-4 hours).

- Sample Preparation: Concentrate the exudate solution using solid-phase extraction (SPE) or lyophilization. Resuspend in appropriate solvent for analysis.

- Analysis: Perform targeted analysis using Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) with multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) for specific alkaloids. Use authentic standards for quantification [8].

Protocol 2: Induction of Alkaloid Biosynthesis by Beneficial Microbes

- Microbial Inoculation: Inoculate plants with beneficial bacteria (e.g., Pseudomonas sp. CH267 or Streptomyces strain AgN23) by adding bacterial suspension to growth medium.

- Time-Course Sampling: Harvest root tissues at various time points post-inoculation (e.g., 0, 6, 12, 24, 48 hours) for gene expression and metabolite analysis.

- Gene Expression Analysis: Extract RNA and perform RT-qPCR to analyze expression of alkaloid biosynthetic genes (e.g., CYP79D15 for cyanogenic glycosides) [9].

- Metabolite Profiling: Analyze alkaloid accumulation using LC-MS/MS with appropriate internal standards [8].

Terpenoids

Structural Diversity and Biosynthesis

Terpenoids, also referred to as isoprenoids, constitute one of the largest and most diverse classes of naturally occurring organic compounds, with over 40,000 unique structures identified [10]. These metabolites are derived from basic five-carbon isoprene units (C5H8) that can be linked in various configurations to form a wide array of structures, from simple linear chains to complex polycyclic molecules [10]. The major subclasses of terpenoids include monoterpenes (C10), sesquiterpenes (C15), diterpenes (C20), triterpenes (C30), and tetraterpenes (C40) [11].

The biosynthesis of terpenoids occurs through two distinct pathways: the mevalonate (MVA) pathway in the cytosol and endoplasmic reticulum, and the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway in the plastids [10] [11]. The MVA pathway utilizes acetyl-CoA as a starting material and primarily produces sesquiterpenes (C15) and triterpenes (C30), while the MEP pathway starts with pyruvate and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate and is responsible for monoterpenes (C10), diterpenes (C20), and tetraterpenes (C40) [10]. The initial precursors, isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP), are condensed by isoprenyl diphosphate synthases (IDSs) to form geranyl diphosphate (GPP), farnesyl diphosphate (FPP), and geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP), which serve as direct precursors for various terpenoid classes [11].

Diagram 1: Terpenoid Biosynthesis Pathways Showing MVA and MEP Routes

Defense Mechanisms and Ecological Roles

Terpenoids play critical roles in plant defense mechanisms, functioning as toxins, repellents, and antimicrobial agents [10]. Their chemical diversity enables a wide range of defensive strategies:

- Insecticidal Action: Terpenoids act as natural insecticides. Limonene, a monoterpene present in citrus peels, effectively repels a variety of insects. Diterpenoids like resin acids found in pine needles are lethal to many herbivorous insects, hindering their digestion and development [10].

- Antifungal Action: Sesquiterpenes are particularly effective against pathogenic fungi. Farnesene, produced by species in the Asteraceae family, inhibits spore germination and impedes fungal growth. The low molecular weight and lipophilic character of terpenoids make them excellent molecules that hinder the sporulation and germination of various fungi, causing cell death [10].

- Plant Communication: Terpenoids are important in plant-communication and plant-insect interactions, such as attracting pollinators or natural predators of herbivores [10]. They also facilitate plant-to-plant communication and improve seed dispersal [11].

Table 2: Major Terpenoid Classes and Their Defensive Functions

| Terpenoid Class | Carbon Atoms | Example Compounds | Natural Sources | Defensive Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monoterpenes | C10 | Limonene, Menthol | Citrus, Mint | Pollinator attraction, Insect repellent |

| Sesquiterpenes | C15 | Artemisinin, Farnesol | Wormwood, Various plants | Antimicrobial, Antimalarial |

| Diterpenes | C20 | Taxol, Ginkgolide | Yew, Ginkgo | Anticancer, Defensive toxins |

| Triterpenes | C30 | Saponins, Steroids | Various plants | Membrane stabilization, Defense |

| Tetraterpenes | C40 | Lycopene, Beta-carotene | Tomatoes, Carrots | Antioxidants, Pigmentation |

Experimental Analysis Protocols

Protocol 1: Analysis of Terpenoid Volatiles

- Headspace Sampling: Place plant material in a sealed container and allow volatiles to accumulate. Use solid-phase microextraction (SPME) fibers to capture volatile terpenoids.

- Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) Analysis: Desorb SPME fibers in GC inlet and separate compounds using a non-polar or slightly polar capillary column.

- Identification and Quantification: Identify compounds by comparison with mass spectral libraries and authentic standards. Use internal standards for quantification [10] [11].

Protocol 2: Induction of Terpenoid Biosynthesis by Herbivory

- Herbivore Treatment: Apply mechanical wounding or allow controlled herbivore feeding on plant leaves.

- Time-Course Sampling: Collect tissue samples at various time points post-induction (0, 1, 3, 6, 12, 24 hours).

- Gene Expression Analysis: Extract RNA and perform RT-qPCR to analyze expression of key terpenoid biosynthesis genes (e.g., DXS, HMGR, terpene synthases).

- Metabolite Analysis: Extract terpenoids with organic solvents (e.g., hexane or dichloromethane) and analyze by GC-MS or LC-MS depending on compound volatility [11].

Phenolics

Structural Diversity and Biosynthesis

Phenolic compounds represent a large family of secondary metabolites characterized by the presence of at least one aromatic ring with one or more hydroxyl groups. Major subclasses include phenolic acids, flavonoids, tannins, lignans, coumarins, and stilbenes [7]. Phenolic acids are further divided into hydroxybenzoic acids (e.g., gallic acid, vanillic acid) and hydroxycinnamic acids (e.g., caffeic acid, ferulic acid, p-coumaric acid) [12].

Phenolic compounds are synthesized primarily through the shikimic acid pathway in plants [7]. This pathway begins with the conversion of shikimic acid into l-phenylalanine (l-Phe) via the action of 5-enolpyruvyl shikimate-3-phosphate synthase, shikimate kinase, and chorismate synthase. Phenylalanine is then converted to p-coumaric acid, salicylic acid (SA), and p-hydroxybenzoic acid (p-HbA), which function as essential precursors for other derivatives of phenolic acids [12]. A key regulatory step is the deamination of phenylalanine to cinnamic acid, catalyzed by the enzyme phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), which is often induced in response to stress and microbial infection [12] [13].

Defense Mechanisms and Ecological Roles

Phenolic compounds play multifaceted roles in mediating the dynamic relationships between the host plant and its microbial partners [12]. Their defensive functions include:

- Antimicrobial Activity: Phenolic acids function as signaling molecules, antimicrobial agents, and modulators of plant defense responses [12]. They can interfere with bacterial quorum sensing and restructure microbial communities [12].

- Allelopathy: Phenolic compounds can inhibit the growth of competing plant species through allelopathic effects [12].

- Structural Defense: Compounds like lignin and suberin reinforce cell walls, creating physical barriers against pathogen invasion [7].

- Oxidative Defense: Many phenolics act as potent antioxidants, scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated under stress conditions [7].

Phenolic compounds balance plant resistance and growth by regulating symbiotic relationships with specific microorganisms [12]. They can serve as substrates for specialized microbial growth, creating feedback loops between their metabolisms and soil rhizosphere microorganisms [12].

Experimental Analysis Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Pressure Induction of Phenolic Biosynthesis

- Treatment Application: Subject harvested plant material (e.g., strawberries) to high-pressure (HP) treatment at pressures ranging from 10 to 40 MPa in two or three cycles.

- Extraction: Homogenize tissue in methanol or acetone-water mixture containing 1% HCl. Sonicate and centrifuge to collect supernatant.

- Total Phenolic Content: Determine total phenolic content using the Folin-Ciocalteu method with gallic acid as standard.

- Gene Expression Analysis: Extract RNA and perform RT-qPCR to analyze expression of key biosynthetic genes (PAL, CHS, UFGT) [13].

Protocol 2: Analysis of Root Exudate Phenolics

- Root Exudate Collection: Grow plants in sterile hydroponic system. Collect root exudates by placing roots in sterile distilled water for 2-4 hours.

- Sample Preparation: Concentrate exudates using solid-phase extraction (C18 cartridges). Elute phenolics with methanol.

- Analysis: Separate and quantify individual phenolic acids using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) with diode-array detection. Use authentic standards for identification and quantification [12].

Glycosides

Structural Diversity and Biosynthesis

Glycosides are compounds consisting of a sugar moiety (most commonly glucose) linked to a non-sugar aglycone through a glycosidic bond. In plant defense, the most significant glycosides include cyanogenic glycosides (CGs) and glucosinolates. This review will focus on cyanogenic glycosides as representative defensive glycosides.

Cyanogenic glycosides are characterized by their ability to release hydrogen cyanide upon enzymatic hydrolysis. Currently, 112 distinct CGs are known from the plant kingdom [14]. Chemically, CGs are α-hydroxynitrile glucosides consisting of two main components: a sugar moiety and an aglycone containing the cyanogenic group (CN) [14]. The aglycone can vary in its chemical structure, appearing as aliphatic, cyclic, aromatic, or heterocyclic compounds, which largely determines the toxicity of CGs [14].

Cyanogenic glycosides are primarily derived from aliphatic amino acids (L-valine, L-isoleucine, L-leucine) and aromatic amino acids (L-phenylalanine, L-tyrosine) [14]. The biosynthesis involves three conserved enzymatic steps:

- Amino acid hydroxylation: Conversion of α-amino acids to aldoximes via N-hydroxylated derivatives, mediated by cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP79).

- Cyanohydrin formation: Transformation of aldoximes into unstable cyanohydrins via further P450 cytochrome enzymes (CYP71, CYP706, CYP736).

- Glycosylation: Attachment of a glucose unit, which stabilizes the cyanohydrins into cyanogenic glucosides, catalyzed by UDP-glucosyltransferase (UGT85, UGT94) [14].

Diagram 2: Cyanogenic Glycoside Biosynthesis and Activation Pathway

Defense Mechanisms and Ecological Roles

Cyanogenic glycosides play a crucial role in plant defense against herbivores and pathogens [14]. The defensive function is not provided by the CG itself, but rather by the toxic hydrogen cyanide (HCN) released from stored CGs when plant tissues are disrupted [14]. Cyanogenesis occurs in two phases: Phase 1 involves cleavage of the carbohydrate component by β-glucosidases, and Phase 2 involves cleavage of the aglycone to aldehyde or ketone and HCN by hydroxynitrile lyases [14].

Plants have evolved compartmentalization strategies to prevent self-toxicity. While CGs are stored in vacuoles, β-glucosidases are localized in the apoplastic space, bound to cell walls in dicotyledonous plants, and in the cytoplasm and chloroplasts in monocotyledonous plants. Hydroxynitrile enzymes accumulate mainly in the cytoplasm and plasma membranes. When plant tissue is disrupted, CGs and enzymes come into contact, leading to HCN release [14].

Beyond defense, CGs also serve as a re-mobilizable reservoir of reduced nitrogen, increase plant tolerance by reducing oxidative stress, and may support seedling development [14]. Additionally, free cyanide, including that released from CGs, may act as a signaling molecule in plants [14].

Experimental Analysis Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantification of Cyanogenic Potential

- Tissue Preparation: Grind plant tissue in liquid nitrogen to fine powder.

- Enzymatic Hydrolysis: Incubate tissue with distilled water in sealed containers. Add enzyme preparation (e.g., β-glucosidase) if needed for complete hydrolysis.

- HCN Detection: Use picrate paper (Feigl-Anger paper) placed in the container headspace to detect released HCN through color change from yellow to reddish brown.

- Quantification: For precise quantification, trap released HCN in NaOH solution and determine cyanide concentration spectrophotometrically or using ion-specific electrode [14].

Protocol 2: Analysis of Cyanogenic Glycoside Polymorphism

- Population Sampling: Collect leaf tissue from multiple individuals in a natural population.

- Screening for Cyanogenesis: Perform quick test using picrate paper on crushed leaves.

- Genotyping: Extract DNA and use PCR-based markers to identify presence/absence of genes responsible for both the synthesis of CGs (Ac) and the synthesis of β-glucosidases (Li).

- Correlation Analysis: Correlate phenotypic cyanogenesis with genotypic data to determine polymorphism patterns [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Plant Defensive Metabolites

| Reagent/Technique | Application | Function/Principle | Representative Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS (Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry) | Alkaloid, phenolic, and glycoside analysis | Separation and sensitive detection of non-volatile metabolites | Quantification of root exudate alkaloids [8] |

| GC-MS (Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry) | Terpenoid and volatile analysis | Separation and identification of volatile compounds | Analysis of herbivore-induced terpenes [10] [11] |

| Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent | Total phenolic content | Colorimetric quantification of phenolics | Measuring induced phenolic biosynthesis [13] |

| Picrate Paper | Cyanogenic glycoside detection | Color change indicates HCN release | Screening for cyanogenesis polymorphism [14] |

| Hydroponic Culture Systems | Root exudate collection | Sterile collection of root-secreted metabolites | Studying alkaloid secretion dynamics [8] |

| RT-qPCR (Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR) | Gene expression analysis | Quantification of biosynthetic gene expression | Monitoring pathway induction under stress [9] [13] |

| SPME (Solid-Phase Microextraction) | Volatile collection | Headspace sampling of volatile compounds | Capturing terpenoid emissions [10] [11] |

The major classes of defensive secondary metabolites—alkaloids, terpenoids, phenolics, and glycosides—represent sophisticated chemical solutions that plants have evolved to navigate complex ecological challenges. Each class employs distinct biosynthetic pathways and mechanisms of action, yet collectively they form an integrated defensive network that enhances plant resilience and fitness. Understanding these compounds extends beyond fundamental plant biology, offering applications in sustainable agriculture through the development of naturally protected crops, and in pharmaceutical science through the discovery of novel bioactive compounds. As research continues to unravel the complexity of these metabolic networks, particularly through advanced omics technologies and synthetic biology approaches, we move closer to harnessing the full potential of plant defensive metabolites for agricultural, medicinal, and ecological benefits.

Secondary metabolites are fundamental to plant survival, enabling adaptation to environmental stresses and defense against pathogens and herbivores. Their biosynthesis is a primary focus of plant defense research, with industrial applications in pharmaceuticals, agriculture, and nutraceuticals [4] [15]. These compounds are not merely "secondary" but are essential for plant resilience and ecological interaction [16]. The biosynthetic pathways responsible for this chemical diversity are highly inducible, often activated by specific environmental stimuli and stresses [17] [18].

This technical guide details the three core biosynthetic pathways for plant secondary metabolites: the shikimic acid, mevalonate (MVA), and methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathways. It provides an in-depth examination of their biochemistry, regulation, and role in plant defense, supported by current research data, experimental protocols, and analytical tools for researchers and drug development professionals.

The Shikimic Acid Pathway

The shikimate pathway is a seven-step metabolic process converting phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) and erythrose 4-phosphate (E4P) into chorismate, the primary precursor for the aromatic amino acids phenylalanine (Phe), tyrosine (Tyr), and tryptophan (Trp) [19]. This pathway is present in bacteria, fungi, algae, and plants, but is absent in animals, making it an attractive target for herbicides and antimicrobials [19]. The pathway's intermediates are highly functionalized, making them ideal branch points for specialized metabolism, leading to a vast array of secondary metabolites [19].

Key Enzymes and Metabolic Branch Points

The architecture of shikimate pathway enzymes varies significantly across kingdoms. Bacteria typically use discrete monofunctional enzymes (aro homologs), plants use six enzymes (including a bifunctional DHQ dehydratase/shikimate dehydrogenase), and fungi employ a pentafunctional AROM complex [19]. Chorismate, the pathway endpoint, serves as the crucial branch point, directing carbon flux into multiple specialized metabolic streams via enzymes like chorismate mutase (for Phe and Tyr biosynthesis) and anthranilate synthase (for Trp biosynthesis) [19] [18].

Defense-Related Metabolites and Stress Regulation

The shikimate pathway provides the aromatic precursors for numerous defense compounds. Phenylalanine is a common precursor for phenolics, flavonoids, lignins, lignans, and condensed tannins [18] [15]. Tyrosine leads to isoquinoline alkaloids and quinones, while tryptophan is the precursor for indole alkaloids, phytoalexins, and auxin [18]. The pathway is transcriptionally upregulated under stress conditions, with key genes regulated by transcription factors such as WRKY, MYB, and AP2/ERF [18].

Table 1: Key Secondary Metabolite Classes Derived from the Shikimate Pathway and Their Defense Roles

| Precursor | Secondary Metabolite Class | Example Compounds | Documented Role in Plant Defense |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenylalanine | Phenolics | Ferulic acid, Caffeic acid | Antioxidants, structural barriers [4] [15] |

| Flavonoids | Quercetin, Anthocyanins | UV protection, herbivore deterrents [4] [20] | |

| Lignins & Lignans | Lignin polymer | Structural reinforcement of cell walls [4] [18] | |

| Tyrosine | Alkaloids | Isoquinoline alkaloids | Toxicity to herbivores and microbes [18] |

| Quinones | Plastoquinone | Redox reactions, oxidative stress mitigation [18] | |

| Tryptophan | Alkaloids & Phytoalexins | Indole alkaloids | Antimicrobial, insecticidal activities [18] |

The diagram below illustrates the core shikimic acid pathway and its major branches leading to defense metabolites.

The Mevalonate (MVA) and Methylerythritol Phosphate (MEP) Pathways

Parallel Routes to Isoprenoid Building Blocks

The mevalonate (MVA) and methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathways are two independent metabolic routes that produce the universal five-carbon isoprenoid precursors, isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and its isomer dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) [21] [22]. Despite producing identical end products, they employ distinct starting substrates, enzymes, and are compartmentalized within different subcellular locations [22] [15].

The MVA pathway is primarily cytosolic and peroxisomal, initiating from three molecules of acetyl-CoA. A key regulatory, rate-limiting step is the conversion of HMG-CoA to mevalonate, catalyzed by HMG-CoA reductase (HMGR) [22] [15]. This pathway primarily supplies precursors for sesquiterpenes (C15), triterpenes (C30), and sterols [15].

The MEP pathway is plastidial and starts with the condensation of pyruvate and D-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GAP). The first committed step, catalyzed by DXP synthase (DXS), is a major regulatory point [22]. This pathway provides IPP and DMAPP for monoterpenes (C10), diterpenes (C20), carotenoids (C40), and the side chains of chlorophylls and plastoquinones [22].

Pathway Coordination and Defense Roles of Terpenoids

In plants, the simultaneous operation of both pathways is a key evolutionary adaptation [22]. This compartmentalization allows for the efficient and specific production of distinct terpenoid classes while minimizing substrate competition [22]. Evidence from mutant studies, chemical inhibition, and isotopic labeling confirms a limited but regulated cross-talk between the cytosolic and plastidial pools of precursors [22]. The terpenoids produced play critical and diverse roles in direct and indirect plant defense, functioning as toxins, repellents, antioxidants, and antimicrobials [4] [22] [20].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of the MVA and MEP Pathways

| Feature | Mevalonate (MVA) Pathway | Methylerythritol Phosphate (MEP) Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Subcellular Location | Cytosol, Endoplasmic Reticulum, Peroxisomes [22] | Plastids [22] |

| Primary Substrates | 3 x Acetyl-CoA [22] [15] | Pyruvate + Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate (GAP) [22] |

| Key Regulatory Enzyme | HMG-CoA Reductase (HMGR) [22] | DXP Synthase (DXS) [22] |

| Energy/Redox Cost | 3 ATP, 2 NADPH per IPP [22] | 3 ATP, 3 NADPH per IPP [22] |

| Major Defense Terpenoids | Sesquiterpenes (C15), Triterpenes (C30) [22] [15] | Monoterpenes (C10), Diterpenes (C20), Tetraterpenes (Carotenoids-C40) [22] [15] |

| Sensitivity to Oxidative Stress | Lower (No Fe-S cluster enzymes in eukaryotic version) [23] | Higher (Due to oxygen-sensitive Fe-S cluster enzymes IspG & IspH) [23] |

The MEP Pathway as an Oxidative Stress Sensor

Recent research highlights a sophisticated role for the MEP pathway beyond precursor supply. Its terminal enzymes, IspG and IspH, contain oxygen-sensitive [4Fe-4S] clusters, making the pathway a sensor for oxidative stress [23]. Under such stress, the intermediate methylerythritol cyclodiphosphate (MEcPP) accumulates and acts as a stress signaling molecule—a function conserved from bacteria to plants [21] [23]. MEcPP may also directly act as an antioxidant, positioning the MEP pathway as a central regulatory node in integrating stress perception with defense metabolism [23].

The following diagram illustrates the two pathways, their compartmentalization, and the major classes of defensive terpenoids they produce.

Experimental Methodologies for Pathway Analysis

Elicitor Treatment for Inducing Secondary Metabolism

Elicitation is a foundational technique for studying inducible defense pathways. It involves exposing plants or in vitro cultures to biotic or abiotic elicitors to trigger secondary metabolite production [17] [20].

Detailed Protocol: Elicitor Treatment in Hairy Root Cultures

- Culture Establishment: Generate and maintain transgenic hairy roots of the target plant species (e.g., Cephalotaxus for alkaloids) by infection with Agrobacterium rhizogenes. Culture in suitable liquid medium (e.g., B5 or MS) under controlled conditions (darkness, 25°C, 100 rpm) [20].

- Elicitor Preparation:

- Biotic Elicitors: Prepare fungal (e.g., Fusarium oxysporum) or yeast extracts by autoclaving biomass, followed by centrifugation and filter-sterilization of the supernatant [17] [20].

- Abiotic Elicitors: Prepare stock solutions of methyl jasmonate (MeJA), salicylic acid (SA), or sodium fluoride (NaF) in ethanol or water, and filter-sterilize [20].

- Treatment: Add the elicitor to the culture medium during the mid-exponential growth phase (e.g., day 14). Optimize concentration and exposure time (e.g., 100 µM MeJA for 48 hours) [20].

- Harvest: Collect biomass by vacuum filtration. Separately, extract metabolites from the biomass and analyze the culture medium for secreted compounds [20].

Molecular Cloning for Pathway Manipulation

Genetic manipulation is key to validating gene function and enhancing metabolite yield.

Detailed Protocol: CRISPR-Based Gene Editing in Mycobacteria/Marinum * Application: This protocol, adapted from [21], is used to investigate gene essentiality in organisms with dual MEP/MEV pathways. 1. Strain and Culture: Grow Mycobacterium marinum M (ATCC BAA-535) at 30°C in Middlebrook 7H9 liquid medium supplemented with 10% OADC and 0.2% Tween80 [21]. 2. Electrocompetent Cell Preparation: Harvest cells at OD600 0.5–0.8. Wash pelleted cells four times with decreasing volumes of sterile 10% glycerol, resuspending the final pellet in a 20-25x concentrated volume [21]. 3. Electroporation: Mix 200 µL of electrocompetent cells with 5 µL of plasmid DNA (e.g., a CRISPR/dCas9 construct). Electroporate in a 0.2-cm cuvette at 2.5 kV, 25 µF, and 1000 Ω resistance [21]. 4. Recovery and Selection: Recover cells overnight at 30°C in 7H9 medium, then plate on selective 7H10 agar containing appropriate antibiotics (e.g., kanamycin 25 µg/ml). Verify gene replacement or knockdown in 3-6 randomly selected clones via PCR [21].

Analytical Techniques for Metabolic Profiling

- Isotopic Labeling and NMR/Mass Spectrometry: To trace pathway flux and confirm precursor origins. For example, feeding (^{13}\text{C})-labeled glucose and analyzing incorporation patterns via NMR can reveal cross-talk between the MVA and MEP pathways [22].

- Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS): The workhorse for quantitative metabolite profiling. Used to measure changes in the levels of pathway intermediates (e.g., DOXP, CDP-ME, MEcPP) and final terpenoid/alkaloid products in response to genetic or elicitor treatments [21] [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying Plant Secondary Metabolic Pathways

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Methyl Jasmonate (MeJA) | Potent abiotic elicitor; activates defense signaling via the JA pathway. | Dramatically enhances alkaloid (e.g., harringtonine) yield in Cephalotaxus cell cultures [20]. |

| Salicylic Acid (SA) | Phenolic phytohormone and elicitor; regulates systemic acquired resistance. | Upregulates the MEP/MVA pathways to boost precursor supply for terpenoid biosynthesis [20]. |

| Fosmidomycin | Specific inhibitor of DXP reductoisomerase (IspC) in the MEP pathway. | Experimentally blocks the plastidial pathway to study its contribution and pathway cross-talk [22]. |

| Lovastatin | Competitive inhibitor of HMG-CoA reductase in the MVA pathway. | Inhibits the cytosolic pathway to dissect its role in sesquiterpene and sterol biosynthesis [22]. |

| Deuterated ((^{2}\text{H})) or (^{13}\text{C}) Glucose | Stable isotope-labeled precursor for metabolic flux analysis. | Traces carbon allocation through the MVA vs. MEP pathways using GC- or LC-MS [22]. |

| Glyphosate | Herbicide; inhibits EPSP synthase in the shikimate pathway. | Used to study the shikimate pathway's role in defense and to select for transgenic glyphosate-resistant plants [19]. |

| Agrobacterium rhizogenes | Natural genetic engineer; used to create "hairy root" cultures. | Generates transformed root cultures that often exhibit high and stable production of secondary metabolites [20]. |

The shikimic acid, mevalonate, and methylerythritol phosphate pathways form the metabolic core of plant chemical defense. Their intricate regulation, compartmentalization, and responsiveness to environmental stresses underscore the sophistication of plant adaptive strategies. Future research, leveraging multi-omics approaches, CRISPR-based gene editing, and metabolic engineering, will continue to unravel the complex regulatory networks governing these pathways. This knowledge is pivotal for developing novel strategies for crop improvement, sustainable production of high-value plant-derived pharmaceuticals, and the discovery of new bioactive compounds for drug development.

Plants, as sessile organisms, cannot escape biotic and abiotic stressors and have consequently evolved a sophisticated array of chemical defense strategies. Central to these strategies are plant secondary metabolites (PSMs), which include a vast range of compounds such as alkaloids, terpenoids, phenolics, and flavonoids [24]. These metabolites are not directly involved in primary growth processes but are indispensable for plant survival and ecological interactions [24]. Defense mechanisms can be broadly categorized as either constitutive (always present) or induced (activated upon threat perception), representing a critical trade-off in a plant's resource allocation budget [24] [25].

The Optimal Defense Theory (ODT) posits that plants evolutionarily tailor their defense investment to protect their most valuable and vulnerable tissues while minimizing metabolic and ecological costs [26]. This framework is essential for understanding the dynamic allocation of defenses, wherein phytoalexins—a class of inducible, antimicrobial secondary metabolites—serve as a classic example of a rapidly deployed, cost-effective defense [24]. The production of these specialized metabolites is tightly regulated by complex signaling networks involving hormones like jasmonic acid (JA), salicylic acid (SA), and ethylene (ETH), which integrate environmental cues to orchestrate an appropriate defense response [27] [28].

This whitepaper delves into the mechanisms governing constitutive and induced plant defenses, with a specific focus on phytoalexins. It examines the molecular basis of metabolic allocation, the signaling pathways involved, and the experimental methodologies driving discovery in this field, providing a resource for researchers and drug development professionals exploring plant-derived bioactive compounds.

Core Concepts: Constitutive and Induced Defenses

Defining the Defense Paradigms

Plant chemical defenses are strategically partitioned into two primary modes:

Constitutive Defenses: These are pre-formed physical and chemical barriers present in plant tissues regardless of threat level. They include structures like trichomes and thick cuticles, as well as metabolites such as tannins and alkaloids, which act as immediate deterrents or toxins to herbivores and pathogens [24] [26]. Their allocation is spatially optimized; for instance, according to ODT, valuable organs like taproots contain higher concentrations of defensive glucosinolates than less critical fine roots [26].

Induced Defenses: These are activated only upon recognition of a specific stress, such as herbivore feeding or pathogen attack [24]. This on-demand system includes the synthesis of phytoalexins and defensive proteins, allowing the plant to conserve resources in the absence of threat [24] [25]. Induced responses are a form of phenotypic plasticity, shaped by the balance between the benefits of reduced herbivory and the metabolic costs of production [25].

The Phytoalexin Response

Phytoalexins are low-molecular-weight, antimicrobial secondary metabolites that are rapidly synthesized de novo and accumulate at sites of pathogen infection [24] [29]. They are a cornerstone of the induced defense system. Their biosynthesis is a complex chemical defense mechanism triggered by elicitors derived from pathogens or abiotic stressors [29]. The production of phytoalexins is often localized and transient, representing a targeted and metabolically efficient defense strategy.

The Dynamics and Economics of Metabolic Allocation

The Optimal Defense Theory (ODT) and Allocation Patterns

The Optimal Defense Theory (ODT) provides a framework for understanding patterns of defense investment in plants. It suggests that defenses are allocated to maximize fitness benefits relative to their costs, prioritizing the most valuable and vulnerable organs [26]. For example, in root systems, taproots often show higher concentrations of defensive compounds like glucosinolates than lateral or fine roots, reflecting their greater importance for plant survival and resource storage [26].

Quantifying the Costs of Defense

Producing secondary metabolites incurs significant costs, which can be metabolic (diversion of resources from growth and reproduction) and ecological (deterrence of beneficial organisms) [26] [25]. A tiered defense strategy minimizes these costs: plants first deploy cheaper defenses and only activate more costly ones after a specific damage threshold is reached [25].

Table 1: Cost-Benefit Analysis of Selected Plant Defense Traits

| Defense Trait | Class / Type | Production Cost | Induction Threshold | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorogenic Acid | Phenolic (Small Molecule) | Low | Continuous, Low Damage | Direct toxin, metabolic inhibitor [25] |

| Trichomes | Structural Defense | High | High (~40% Damage) | Physical barrier against herbivores [25] |

| Condensed Tannins | Phenolic (Polymer) | High | High (~40% Damage) | Reduces plant digestibility [25] |

| Phytoalexins | Induced Chemical | Variable | Pathogen Recognition | Direct antimicrobial activity [24] [29] |

Research on common ragweed demonstrates that cheaper traits (e.g., chlorogenic acid, kaempferol, rutin) exhibit a linear induction response to damage, while costlier traits (e.g., trichomes, condensed tannins, lignin) are induced only after a high damage threshold (approximately 40%) is crossed [25]. This sequential activation forms a tiered defense system that balances cost-efficiency with robust protection.

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

Biosynthetic Pathways of Key Secondary Metabolites

The biosynthesis of PSMs, including phytoalexins, proceeds through several major pathways, often stemming from primary metabolism [4] [15].

- The Shikimate Pathway: This pathway produces aromatic amino acids (phenylalanine, tyrosine, tryptophan) which are precursors for a vast array of phenolics, including flavonoids, lignins, and tannins [4] [15].

- The Phenylpropanoid Pathway: Converting phenylalanine from the shikimate pathway, this route generates phenolic compounds like flavonoids, lignins, and stilbenes (e.g., resveratrol, a phytoalexin in grapes) [15].

- The Mevalonate (MVA) and Methylerythritol Phosphate (MEP) Pathways: These pathways produce the basic five-carbon building blocks (IPP and DMAPP) for terpenoids, which include monoterpenes, diterpenes, and sesquiterpenes with defensive roles [4] [27] [15].

- Alkaloid Biosynthesis: Derived from various amino acids, alkaloids represent a major class of nitrogen-containing defensive compounds [24] [15].

Signaling Networks in Induced Defense

The induction of phytoalexins and other defenses is governed by a complex signaling network. Key players include:

- Jasmonates (JA/MeJA): Central regulators of defense against necrotrophic pathogens and herbivores. JA signaling often promotes the production of alkaloids, terpenoids, and phenolic phytoalexins [27] [29].

- Salicylic Acid (SA): Primarily involved in defense against biotrophic pathogens and systemic acquired resistance (SAR). There can be crosstalk and antagonism between SA and JA pathways [30] [28].

- Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Gasotransmitters: Molecules like hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), nitric oxide (NO), and hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) act as secondary messengers in stress signaling, modulating the biosynthesis of SMs [27].

- Transcription Factors (TFs): Families such as MYB, WRKY, bHLH, and AP2/ERF are crucial integrators of these signals, binding to promoters of biosynthetic genes to activate the production of phytoalexins and other defensive metabolites [28].

The following diagram summarizes the key signaling pathways and their crosstalk in the induction of phytoalexin biosynthesis:

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Studying constitutive and induced defenses requires integrated multi-omics approaches to link physiological responses to underlying molecular changes. The following workflow, derived from a study on Coptis chinensis defense against root rot, provides a robust template for such investigations [30].

Detailed Experimental Workflow

1. Experimental Design and Plant Material [30]

- Establish distinct experimental groups (e.g., resistant controls, early-infected, late-infected plants).

- Use genetically uniform plant material to reduce biological noise.

- Apply controlled stress (e.g., mechanical wounding, application of herbivore oral secretions, pathogen spores, or chemical elicitors like methyl jasmonate).

2. Tissue Sampling and Preparation [30]

- Collect plant tissues (e.g., leaves, roots) at multiple time points post-stress to capture dynamics.

- Flash-freeze samples immediately in liquid nitrogen to preserve RNA and metabolite integrity.

- Store samples at -80°C until analysis.

3. Multi-Omics Data Acquisition

- Transcriptomics (RNA-Seq) [30]

- Extract total RNA using a validated kit (e.g., CTAB-PBIOZOL method).

- Prepare sequencing libraries (e.g., Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA Kit) and sequence on a platform like Illumina NovaSeq (paired-end 150 bp).

- Process raw reads: trim adapters/low-quality sequences (Trimmomatic), align to a reference genome (HISAT2), and quantify gene expression (e.g., FPKM using StringTie).

- Identify Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) using tools like DESeq2 (|log2(fold change)| > 1.5, adjusted p-value < 0.05).

- Metabolomics (LC-MS/MS) [30]

- Extract metabolites from homogenized tissue using a methanol-acetonitrile-water system.

- Analyze extracts via UHPLC-MS/MS (e.g., Thermo Fisher Vanquish UHPLC coupled to Q Exactive HF-X mass spectrometer).

- Use reverse-phase chromatography (e.g., HSS T3 column) with a water-acetonitrile gradient.

- Acquire data in both positive and negative ionization modes.

- Process raw data (peak alignment, normalization, metabolite annotation) using software like Progenesis QI and databases (HMDB, KEGG).

4. Integrative Bioinformatic Analysis [30]

- Perform Pearson correlation analysis between DEGs and Differentially Accumulated Metabolites (DAMs) (|r| > 0.8, p < 0.01) to construct gene-metabolite networks.

- Conduct joint pathway enrichment analysis (KEGG) to identify activated biosynthetic and signaling pathways.

5. Experimental Validation [30]

- Select key DEGs (e.g., from phenylpropanoid/flavonoid pathways: PAL, CHS, FLS) for validation by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR).

- Use a reference gene (e.g., Rubisco) for normalization and the 2^(-ΔΔCt) method for relative quantification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Kits for Plant Defense Metabolomics Research

| Reagent / Kit Name | Function / Application | Key Features / Target Genes |

|---|---|---|

| CTAB-PBIOZOL RNA Extraction Method | High-quality total RNA extraction from challenging plant tissues [30] | Effective for polysaccharide and polyphenol-rich tissues; yields RNA for NGS. |

| Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep Kit | Preparation of sequencing libraries for transcriptomics [30] | Maintains strand specificity, enabling accurate transcriptome mapping. |

| HISAT2, StringTie, DESeq2 Software Suite | Bioinformatic analysis of RNA-Seq data (alignment, assembly, differential expression) [30] | Standard, reproducible pipeline for identifying stress-responsive DEGs. |

| HSS T3 UHPLC Column (Waters) | Chromatographic separation of complex metabolite extracts [30] | High-resolution separation of diverse secondary metabolites. |

| Progenesis QI Software (Waters) | LC-MS metabolomics data processing (peak picking, alignment, statistical analysis) [30] | Non-targeted analysis platform for identifying DAMs. |

| Methyl Jasmonate (MeJA) | Chemical elicitor to simulate herbivore attack and induce JA pathway [27] | Induces biosynthesis of terpenoids, alkaloids, and phenolics; used in time-course experiments. |

| Gene-Specific qPCR Primers (e.g., for PAL, CHS, FLS) | Validation of transcriptomic data [30] | Confirms upregulation of key genes in phenylpropanoid/flavonoid pathways. |

The strategic allocation of resources between constitutive and induced defenses, exemplified by the rapid synthesis of phytoalexins, is a cornerstone of plant resilience. The integration of advanced omics technologies is systematically unraveling the complex signaling networks and biosynthetic pathways that govern this dynamic process. The principles of ODT and the tiered, cost-sensitive deployment of defenses provide a powerful conceptual framework for interpreting these molecular findings.

This knowledge is invaluable for translational applications. In agriculture, it informs the development of novel crop protection strategies, such as breeding or engineering plants with optimized defense portfolios for enhanced resistance [24] [4]. For drug discovery, understanding the induction and biosynthesis of phytoalexins and other PSMs opens avenues for producing high-value plant-derived pharmaceuticals, both in planta and through metabolic engineering in microbial or plant cell culture systems [24] [29]. Continued research into the dynamics of metabolic allocation will undoubtedly yield deeper insights and innovative tools for sustainable agriculture and medicine.

Secondary metabolites (SMs) are organic compounds not directly involved in the normal growth, development, or reproduction of plants, but which play indispensable roles in survival and fitness by mediating interactions with the environment [31]. These specialized compounds serve as powerful regulators of plant defense and communication, forming a sophisticated chemical arsenal against biotic and abiotic challenges [32] [27]. Within the broader thesis on the role of secondary metabolites in plant defense research, this whitepaper examines four core ecological functions: deterrence against herbivores, direct toxicity to pests and pathogens, antimicrobial activity against microorganisms, and allelopathy against competing plants. Understanding these mechanisms provides not only fundamental ecological insights but also opens avenues for therapeutic discovery and sustainable agricultural development [33]. This technical guide synthesizes current research on SM functions, experimental methodologies, underlying molecular mechanisms, and practical applications for researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Ecological Functions of Secondary Metabolites

Deterrence and Toxicity

Plants produce a diverse array of secondary metabolites that serve as powerful deterrents and toxins against herbivores, insects, and other predators. These compounds function through various mechanisms including anti-feedant activity, interference with digestion, neurotoxicity, and disruption of essential physiological processes [34].

Table 1: Major Classes of Defensive Secondary Metabolites and Their Toxic Mechanisms

| Metabolite Class | Representative Compounds | Target Organisms | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkaloids | Nicotine, Caffeine, Quinine | Herbivorous insects, mammals | Binds to neuroreceptors, disrupts nerve signaling [34] |

| Cyanogenic Glucosides | Dhurrin, Amygdalin | Generalist herbivores | Releases toxic hydrogen cyanide upon tissue damage [34] [35] |

| Glucosinolates | Sinigrin, Glucobrassicin | Insects, generalist herbivores | Forms toxic isothiocyanates (e.g., mustard oils) upon hydrolysis by myrosinase enzyme [34] |

| Ribosome-Inactivating Proteins (RIPs) | Ricin, Abrin | Insects, mammals | Catalytically inactivates ribosomes, halting protein synthesis [36] |

| Protease Inhibitors | Trypsin inhibitor | Insects | Inhibits digestive proteases, impairing nutrient absorption [36] |

| Lectin | Phytohemagglutinin | Insects, mammals | Binds to carbohydrates, disrupting cell adhesion and causing agglutination [36] |

The ecological significance of these compounds is profound. For example, the well-studied glucosinolate-myrosinase system in Brassicales represents a "mustard oil bomb" – when plant tissue is damaged, the substrate and enzyme mix, producing pungent and toxic hydrolysis products that deter feeding [34]. Similarly, cyanogenic glycosides like amygdalin in apple seeds sequester cyanide in a non-toxic form, releasing it only upon predator attack, thus providing an effective chemical defense while avoiding self-intoxication [35].

Antimicrobial Properties

Secondary metabolites constitute a primary defense line against bacterial, fungal, and viral pathogens. Their antimicrobial activities arise from diverse biochemical mechanisms that target essential microbial structures and functions.

Table 2: Antimicrobial Secondary Metabolites and Their Mechanisms of Action

| Metabolite Class | Example Compounds | Target Microorganisms | Antimicrobial Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenolics & Polyphenols | Caffeic acid, Gallic acid, Quercetin, Catechin | Gram-positive bacteria (e.g., S. aureus), Fungi | Membrane disruption, enzyme inhibition, protein binding [37] [33] |

| Flavonoids | Apigenin, Genkwanin, Kaempferol | Vibrio cholerae, E. faecalis, M. tuberculosis | Membrane permeabilization, nucleic acid intercalation, β-glucan synthase inhibition [37] |

| Terpenoids | Monoterpenes (Menthol, Pinene) | Bacteria, Fungi | Membrane disintegration, mitochondrial dysfunction [27] |

| Alkaloids | Berberine, Sanguinarine | Bacteria, Fungi | DNA intercalation, enzyme inhibition [32] |

| Naphthoquinones | Lapachol, Diospyrin | Candida albicans, H. pylori | Redox cycling, generating reactive oxygen species [37] |

| Sulfur-containing (Glucosinolates) | Sinigrin | Fungi, Bacteria | Isothiocyanate products inactivate microbial enzymes [34] [27] |

The structural diversity of SMs enables multi-target antimicrobial actions, reducing the likelihood of resistance development. Phenolics like those found in sage (Salvia officinalis) and pomegranate (Punica granatum) exhibit both bactericidal and bacteriostatic effects by disrupting cell membranes and inactivating enzymes [37]. Flavonoids such as quercetin and kaempferol demonstrate broad-spectrum activity against foodborne pathogens and mycobacteria [37] [33]. This multi-target mechanism is particularly valuable in an era of rising antibiotic resistance, making plant SMs promising candidates for novel antimicrobial development [33].

Allelopathy

Allelopathy refers to the phenomenon where plants release biochemicals into the environment that influence the germination, growth, survival, and reproduction of other organisms, typically competing plants [38]. These allelochemicals provide a competitive advantage by directly inhibiting neighboring species and altering soil microbial communities.

Key Allelopathic Plants and Their Compounds:

- Black Walnut (Juglans nigra): Releases juglone, a naphthoquinone that inhibits respiration and energy metabolism in sensitive plants [38].

- Tree of Heaven (Ailanthus altissima): Produces ailanthone in its roots, which disrupts root development of competitors [38].

- Spotted Knapweed (Centaurea stoebe): Historically associated with catechin, though its role remains controversial [38].

- Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata): Excretes glucosinolates like sinigrin that disrupt mutualisms between native tree roots and mycorrhizal fungi [38].

- Rice (Oryza sativa): Certain cultivars release phenolic acids, flavonoids, and terpenoids that suppress weeds [38].

The distinction between allelopathy and resource competition is critical. While resource competition involves depletion of abiotic factors (light, water, nutrients), allelopathy operates through the direct addition of inhibitory chemicals to the environment [38]. However, these processes often operate concurrently in natural systems. The application of allelopathy in agriculture, through breeding allelopathic crop cultivars or using plant residues as natural herbicides, offers promising sustainable weed management strategies [38].

Experimental Protocols for Studying Secondary Metabolites

Screening for Antimicrobial Activity

Protocol 1: Primary Screening Using Agar Plug Diffusion Method [39]

- Culture Preparation: Grow the bacterial isolate of interest on solid nutrient medium for 2-3 days until good growth appears.

- Test Pathogen Lawn: Prepare a suspension of the target pathogen (e.g., E. coli, S. aureus) equivalent to the 0.5 McFarland standard. Spread 100 µL evenly on Mueller-Hinton Agar (MHA) plates.

- Agar Plug Collection: Using a sterile cork borer (6 mm diameter), cut plugs of the bacterial isolate from the culture plate.

- Inoculation and Incubation: Aseptically place the agar plugs on the surface of the seeded MHA plates. Incubate at 37°C for 24 hours.

- Analysis: Measure the zones of inhibition (clear areas) surrounding the plugs. Isolates showing significant inhibition are selected for secondary screening.

Protocol 2: Secondary Screening and Metabolite Extraction via Agar Well Diffusion [39]

- Fermentation: Inoculate the selected isolate into Mueller-Hinton Broth and incubate at 28±2°C with shaking for 7-9 days.

- Culture Harvesting: Centrifuge the culture at 10,000 × g for 5 minutes to obtain a cell-free supernatant (crude extract).

- Well Preparation: Create wells (6 mm diameter) in MHA plates seeded with the test pathogen.

- Extract Application: Load wells with 50 µL and 100 µL of the crude extract. Include appropriate controls (e.g., Ciprofloxacin as a positive control, DMSO as a negative control).

- Incubation and Assessment: Incubate plates at 37°C for 24-48 hours. Measure and record the zones of inhibition to determine antimicrobial efficacy.

Protocol 3: Solvent Extraction of Bioactive Metabolites [39]

- Large-Scale Fermentation: Transfer 0.5 mL of a fresh culture into 500 mL conical flasks containing 200 mL of LB broth. Incubate in a shaking incubator at 30±2°C until the stationary phase is reached (OD₆₀₀ ≈ 3.6).

- Liquid-Liquid Extraction: Mix the culture broth with an equal volume of ethyl acetate (EtAc) in a separatory funnel. Shake vigorously and allow phases to separate.

- Concentration: Collect the organic (EtAc) layer and evaporate it to dryness under reduced pressure in a rotary evaporator.

- Resuspension: Redissolve the dried extract in a minimal volume of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) for bioassay and further chemical analysis (e.g., GC-MS).

Investigating Allelopathy

Protocol: Separating Allelopathic Effects from Resource Competition [38]

Experimental Design: Establish a factorial experiment with the following treatments:

- Treatment A (Control): Donor and receiver plants grown together.

- Treatment B (Reduced Resource Competition): Donor and receiver plants grown with physical barriers (e.g., PVC tubes) inserted into the soil to separate their root systems.

- Treatment C (Reduced Allelopathy): Activated charcoal added to the soil surface to adsorb organic allelochemicals.

- Treatment D (Combined Reduction): Both PVC tubes and activated charcoal applied.

Measurement: Monitor growth parameters (e.g., biomass, root length, germination rate) of the receiver plants over a defined period.

Data Interpretation: Significant growth improvement in Treatment C compared to Control suggests a substantial allelopathic effect. Growth improvement in Treatment B indicates resource competition. The combined treatment helps elucidate potential interactions between these two mechanisms.

Signaling Pathways and Biosynthetic Regulation

The production of secondary metabolites is not constitutive but is highly regulated by complex signaling networks activated in response to biotic and abiotic stresses. Key signaling molecules include nitric oxide (NO), hydrogen sulfide (H₂S), methyl jasmonate (MeJA), hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), ethylene (ETH), melatonin (MT), and calcium (Ca²⁺) ions [27]. These molecules act as messengers, triggering transcriptional reprogramming that leads to the activation of SM biosynthetic pathways.

The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathway that connects an environmental stress signal to the production of defensive secondary metabolites:

Figure 1: Signaling Pathway for Secondary Metabolite Production

For instance, the transcription factor WRKY is a key regulator that influences the production of alkaloids such as taxol in Taxus chinensis and artemisinin in Artemisia annua [27]. The specific classes of SMs produced—terpenes, phenolics, alkaloids, and glucosinolates—depend on the plant species, the type of stress encountered, and the combination of signaling molecules activated [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Secondary Metabolite Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Activated Charcoal | Adsorbs organic allelochemicals in soil, helping to isolate chemical interference from resource competition [38]. | Experimental separation of allelopathy from competition in plant-soil systems [38]. |

| Ethyl Acetate | Organic solvent for extracting medium-polarity secondary metabolites from culture broth or plant tissue [39]. | Liquid-liquid extraction of antimicrobial compounds from bacterial fermentation broth [39]. |

| Mueller-Hinton Agar/Broth | Standardized culture medium for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, ensuring reproducible results [39]. | Agar well diffusion and broth dilution assays for evaluating antimicrobial activity of plant extracts [39]. |

| Jasmonic Acid / Methyl Jasmonate | Plant signaling hormone that elicits defense responses, including the production of specific secondary metabolites [27]. | Treatment of plant cell cultures to enhance the synthesis of terpenoids, alkaloids, and phenolics for study or production [27]. |

| DMSO (Dimethyl Sulfoxide) | Polar aprotic solvent for dissolving and stabilizing a wide range of organic compounds, including plant extracts. | Solubilizing dried plant extracts for bioassay applications and stock solution preparation [39]. |

| Silica Gel | Stationary phase for chromatographic separation and purification of individual secondary metabolites from complex crude extracts. | Column chromatography to isolate pure flavonoids, alkaloids, or terpenoids for structural identification and bioactivity testing. |

| Reverse-Phase C18 Columns | Used in Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) and HPLC for analytical and preparative separation of secondary metabolites based on hydrophobicity. | Purifying and quantifying specific phenolic acids or flavonoids from plant tissue extracts. |

Secondary metabolites represent a cornerstone of plant defense, embodying an intricate evolutionary adaptation to ecological challenges. Their functions in deterrence, toxicity, antimicrobial activity, and allelopathy are mediated by sophisticated biochemical mechanisms and regulated by complex signaling networks. The experimental frameworks and tools outlined in this whitepaper provide a foundation for advancing research in this field. For drug development professionals, plant SMs offer an invaluable reservoir of chemical scaffolds with proven bioactivities, holding significant promise for addressing the critical challenge of antimicrobial resistance. Future research leveraging omics technologies, genetic engineering, and advanced synthetic biology will further unravel the multifaceted roles of these remarkable compounds, driving innovations in both medicine and sustainable agriculture.

Plant secondary metabolites (SMs) constitute a sophisticated biochemical arsenal underpinning plant defense. These compounds, which include terpenes, phenolics, alkaloids, and sulfur-containing compounds, interact with molecular targets in antagonistic organisms through three primary mechanisms: disruption of cellular membranes, inhibition of key enzymes, and interference with signal transduction pathways. This whitepaper delineates the molecular basis of these defense strategies, supported by quantitative data and experimental evidence. Furthermore, it provides detailed methodologies for investigating these interactions and visualizes complex signaling networks, offering a resource for researchers in plant science and drug discovery. The strategic manipulation of these pathways through metabolic engineering presents a promising frontier for developing sustainable crop protection strategies and novel therapeutic agents.

Plants, as sessile organisms, have evolved a complex array of chemical defenses to counteract pathogens, herbivores, and competing plants [29]. Central to these defenses are secondary metabolites (SMs)—over 200,000 of which have been identified—that serve as crucial tools for survival and ecological adaptation [4] [40]. These compounds are not directly involved in primary growth and development but are indispensable for plant resilience and interactions with the environment [41] [40]. The molecular defense strategies employed by SMs can be categorized into three core mechanisms: membrane disruption, which compromises the structural integrity of cellular barriers; enzyme inhibition, which disrupts essential metabolic and catalytic processes in antagonistic organisms; and signal interference, which modulates the complex signaling networks that govern defense responses [42] [43]. Understanding these mechanisms at a molecular level is critical for advancing plant defense research and harnessing these compounds for agricultural and pharmaceutical applications. This review synthesizes current knowledge on these mechanisms, providing a technical guide for researchers and scientists.

Membrane Disruption by Secondary Metabolites

Membrane disruption represents a direct and potent defense mechanism whereby SMs compromise the structural integrity of cellular membranes in pathogens and herbivores. This primarily involves interaction with the lipid bilayer, leading to increased permeability, loss of cellular contents, and ultimately, cell death.

Terpenes and terpenoids, a vast class of SMs with over 25,000 identified structures, are particularly effective at this mode of action [43]. Monoterpenes, such as menthol, linalool, and camphor, exhibit antimicrobial and antioxidant activities. Their lipophilic nature allows them to integrate into and disrupt microbial cell membranes [27]. The process involves the hydrophobic compounds partitioning into the lipid bilayer, disturbing the packing of fatty acyl chains. This increases membrane fluidity and creates pores, leading to the leakage of ions (e.g., K+) and other vital cellular constituents.