Plant Essential Oil Chemistry: Fundamentals for Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the chemistry of plant essential oils, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Plant Essential Oil Chemistry: Fundamentals for Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the chemistry of plant essential oils, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of essential oil composition, including the biosynthesis and classification of terpenes and phenylpropanoids. The scope extends to modern extraction and analysis methodologies, explores the mechanisms behind their diverse pharmacological activities, and addresses critical challenges in their application, such as volatility and low solubility. Furthermore, it evaluates the drug-likeness of essential oil components and discusses advanced formulation strategies to overcome delivery hurdles, synthesizing key insights to highlight their promising potential in clinical and pharmaceutical development.

The Chemical Building Blocks: Biosynthesis and Classification of Essential Oil Components

Essential oils (EOs) are concentrated, hydrophobic liquids containing volatile aromatic compounds from plants. They are defined as secondary metabolites obtained from plant materials through distillation or mechanical methods without heating, representing the quintessential "essence" of a plant's fragrance and biological activity [1]. Chemically, they are complex mixtures of volatile compounds, primarily terpenes, terpenoids, and phenylpropenes, synthesized and stored in various plant organs including leaves, flowers, bark, stems, roots, and seeds [2] [1]. These oils serve critical ecological functions for plants, such as attracting pollinators, repelling herbivores, and providing defense against pathogens [3]. Their immense importance in human applications spans traditional medicine, modern pharmacotherapy, aromatherapy, cosmetics, and food science, driven by their diverse bioactivities including antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer properties [2] [4] [5].

Chemical Composition and Plant Biogenesis

Fundamental Chemical Building Blocks

The chemical architecture of essential oils is predominantly based on isoprene units (C5H8), arranged in a head-to-tail fashion following the isoprene rule [1]. This molecular foundation gives rise to several classes of terpenes, outlined in Table 1, which form the primary constituents of most essential oils.

Table 1: Fundamental Terpene Classes in Essential Oils

| Terpene Class | Number of Isoprene Units | Carbon Atoms | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monoterpenes | 2 | 10 | α-pinene, limonene, myrcene, thujene |

| Sesquiterpenes | 3 | 15 | bisabolene, zingiberene, caryophyllene |

| Diterpenes | 4 | 20 | phytol, retinol, taxol |

| Triterpenes | 6 | 30 | squalene, hopane |

Beyond simple hydrocarbons, essential oils contain oxygenated derivatives of these terpenes—including alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, esters, ethers, and phenols—which often possess greater biological activity and lower volatility than their hydrocarbon precursors [2] [1]. A third significant group are aromatic compounds derived from the shikimate pathway, such as eugenol, thymol, chavicol, and anethole, which are particularly abundant in certain plant families like Lamiaceae and Myrtaceae [2] [3].

Biogenetic Pathways

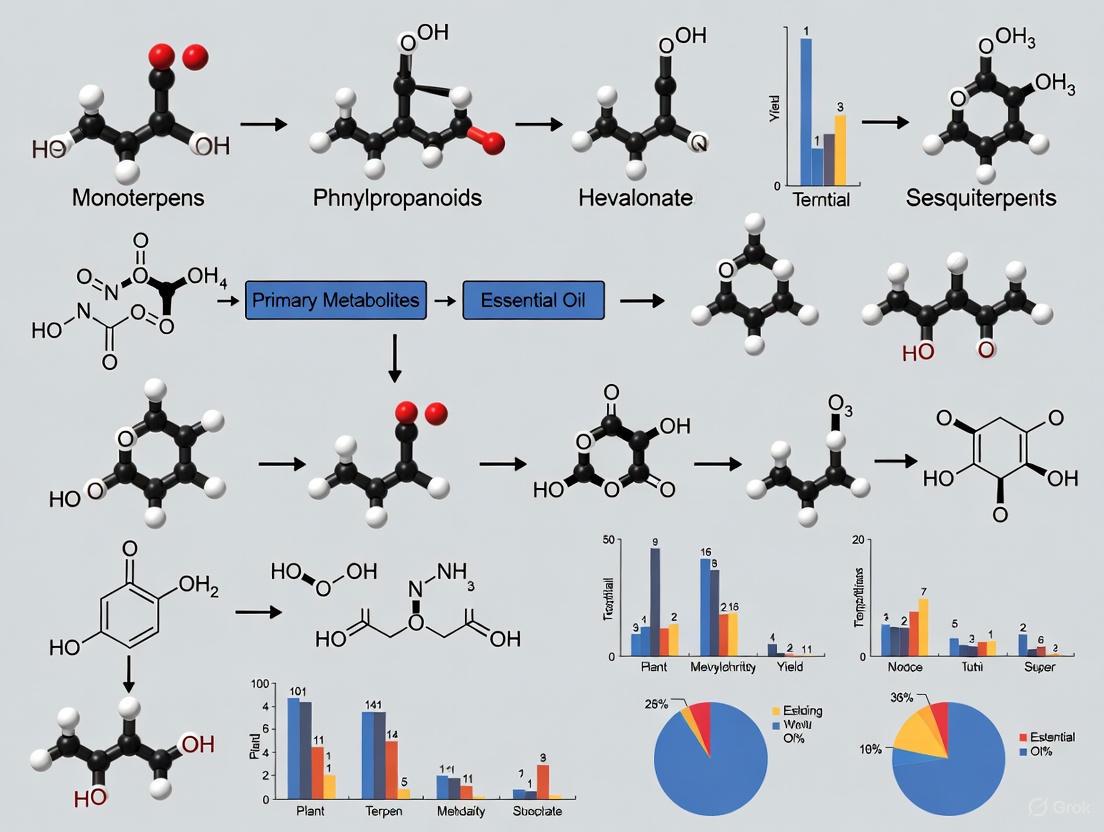

Plants synthesize essential oil constituents through two primary, interconnected biochemical pathways, both originating from photosynthesis-derived glucose, as illustrated below.

Figure 1: Biogenetic Pathways of Essential Oil Components. Essential oils are synthesized in plants via two main pathways: the MEP pathway producing aliphatic terpenes (red) and the shikimate pathway producing aromatic compounds (green).

The pyruvate-mevalonate/methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway is responsible for producing the predominant aliphatic terpenes. This pathway generates the universal terpene precursors, isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP). Enzymatic coupling of these units yields geranyl diphosphate (GPP), the direct precursor to monoterpenes, and farnesyl diphosphate (FPP), the precursor to sesquiterpenes [2]. The shikimate pathway produces aromatic amino acids that serve as precursors for phenylpropanoids—aromatic volatile compounds like eugenol (clove), thymol (thyme), and anethole (anise) that characterize many essential oils [2] [3]. The specific composition and relative abundance of these compounds are influenced by numerous factors, including plant species, geographical origin, environmental conditions, harvest time, and the specific plant organ from which the oil is extracted [2] [1].

Analytical Characterization and Standardization

Comprehensive Chemical Profiling

Rigorous chemical profiling is fundamental to essential oil research, ensuring authenticity, purity, and reproducible bioactivity. The analytical workflow integrates several advanced techniques, with Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) serving as the gold standard for volatile compound analysis [6].

Table 2: Standardized GC-MS Operating Conditions for Essential Oil Analysis

| Parameter | Specification | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Column Type | Fused silica capillary column (e.g., Rtx-5MS, HP-5MS), 30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 µm film thickness | Optimal separation of complex volatile mixtures |

| Temperature Program | Initial 45-60°C (hold 2 min), ramp at 3-5°C/min to 200-300°C (hold 5-7 min) | Resolution of compounds across a wide volatility range |

| Injection | Split or splitless mode, 1:15 to 1:50 split ratio, 230-250°C injector temperature | Controlled sample introduction to prevent column overload |

| Carrier Gas | Helium, constant flow (~1.41 mL/min) | Inert mobile phase for efficient separation |

| Ionization | Electron Impact (EI) at 70 eV | Standardized, reproducible fragmentation for library matching |

| Mass Range | 35-500 m/z | Detection of all relevant volatile compounds |

| Identification | Comparison with NIST, Wiley, Adams databases; Kovats Retention Index calculation | Confident compound identification [7] [4] [8] |

For non-volatile or semi-volatile constituents (e.g., certain phenolics, flavonoids), High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) is employed. A typical protocol for analyzing phenolic compounds in plant extracts uses a C8 or C18 reverse-phase column with a water-acetonitrile gradient mobile phase (often with 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid) and detection at 280 nm [8]. Supplementary techniques include Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) for functional group identification, optical rotation for chiral purity assessment, and refractive index measurement for rapid purity checks [9] [6].

Authentication and Quality Control Protocols

Quality control relies on a multi-parameter approach to detect adulteration—a common issue given the high value of essential oils. Adulterants can include synthetic nature-identical compounds, cheaper essential oils, or vegetable oils [9] [6]. Key authentication strategies include:

- Chemical Fingerprinting: Analyzing the complete chromatographic profile, including peak patterns and relative ratios of key markers, rather than just major components [6].

- Enantiomeric Analysis: Using chiral GC columns to distinguish natural chiral ratios from synthetic racemic mixtures [6].

- Stable Isotope Ratio Analysis: Measuring carbon-13/carbon-12 ratios to differentiate natural from synthetic compounds [6].

- Organoleptic Testing: Trained sensory evaluation of aroma, color, and texture against established references [9].

International standards organizations provide detailed monographs for many essential oils, specifying acceptable ranges for major components, physical constants (density, refractive index, optical rotation), and limits for contaminants. Key standards are set by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), European Pharmacopoeia (Ph. Eur.), and United States Pharmacopeia (USP) [9] [6].

Experimental Bioactivity Assessment

Standardized Bioassay Methodologies

To evaluate the therapeutic potential of essential oils, researchers employ a battery of standardized in vitro bioassays. Key methodologies are detailed below, with quantitative results from recent studies summarized in Table 3.

Antioxidant Activity:

- DPPH Assay: Measures free radical scavenging capacity. A methanolic solution of the stable DPPH radical (0.1-0.3 mM) is mixed with the oil or extract. After 30 minutes in darkness, the decrease in absorbance at 517 nm is measured. Results are expressed as IC50 (concentration providing 50% inhibition), often compared to standards like Trolox or ascorbic acid [7] [8].

- FRAP Assay: Assesses reducing power. The sample is mixed with FRAP reagent (TPTZ in acetate buffer, pH 3.6), and the increase in absorbance at 593 nm, due to the formation of Fe2+-TPTZ complex, is measured after 30 minutes [7].

- ABTS Assay: Evaluates radical cation scavenging. The ABTS•+ radical cation is generated by reacting ABTS solution with potassium persulfate. The reduction in absorbance at 734 nm after adding the sample is measured [8].

Antimicrobial Activity:

- Disk Diffusion Method: Filter paper disks impregnated with the essential oil are placed on agar plates inoculated with test microorganisms. After incubation (e.g., 24h at 37°C), the diameter of the inhibition zone around the disk is measured in millimeters [7].

- Broth Dilution Method: Determines the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC). Serial dilutions of the oil in a broth medium are inoculated with a standardized microbial suspension. The lowest concentration preventing visible growth after incubation is the MIC [4].

Cytotoxicity and Anticancer Activity:

- MTT Assay: A colorimetric assay for cell viability and proliferation. Vero or cancer cell lines are treated with the oil and incubated with MTT reagent (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide). Viable cells reduce MTT to purple formazan crystals, which are solubilized with DMSO, and the absorbance is measured at 570 nm. Cell viability is calculated as a percentage of untreated controls, and IC50 values are determined [4].

Anti-inflammatory and Enzyme Inhibition:

- Anti-acetylcholinesterase (AChE) Assay: Uses Ellman's method to measure AChE inhibition, relevant for neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's [8].

- α-Glucosidase Inhibition: Measures the reduction in conversion of p-nitrophenyl-α-D-glucopyranoside to p-nitrophenol, relevant for antidiabetic activity [4] [8].

Table 3: Quantitative Bioactivity Profiles of Selected Essential Oils (Recent Data)

| Essential Oil (Source) | Major Compounds | Antioxidant (DPPH IC50) | Antimicrobial (Inhibition Zone) | Anticancer (Cytotoxicity IC50) | Other Notable Activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) [7] | α-pinene (21.37%), bornanone (12.73%), eucalyptol (8.28%) | IC50 = 27.30 ± 2.4% (Methanolic Extract) | S. aureus: 33 mm; B. subtilis: 32 mm | Not Reported | Anti-inflammatory (IC50 = 55.88 ± 1.02% for Aqueous Extract) |

| Salvia lanigera [8] | 1,8-cineole (27.28%), camphor (25.82%), α-pinene (7.71%) | Oil IC50 = 0.1337 µg/mL; Extract IC50 = 0.6331 µg/mL | Not Reported | Not Reported | Anti-acetylcholinesterase (IC50 = 144 µg/mL); Antidiabetic (α-glucosidase IC50 = 124.6 µg/mL for extract) |

| Plectranthus amboinicus [4] | Thymol, Citronellol | IC50 = 5923 µg/mL | Not Reported | H1299 lung cancer cells: IC50 = 11 µg/mL | Antidiabetic (α-glucosidase IC50 = 248.1 µg/mL) |

| Mentha canadensis [4] | Menthol, Pulegone | Not Reported | Not Reported | Low cytotoxicity (Vero cell viability >97% at ≤312 µg/mL) | Antiviral (35.34% suppression of Adeno 7 virus) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Essential Oil Research

| Reagent/Material | Specification/Example | Primary Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Clevenger Apparatus | Standard glassware with condenser and oil receiver | Hydrodistillation of essential oils from plant material [4] [8] |

| GC-MS System | e.g., Shimadzu GCMS-QP2010, Agilent 8890/5977B | Definitive chemical characterization and quantification of volatile components [7] [4] [8] |

| HPLC-DAD System | e.g., Agilent 1260 series with C8/C18 column | Analysis of non-volatile components like phenolic acids and flavonoids [8] |

| DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) | ≥ 90% purity (e.g., Sigma-Aldrich) | Free radical for standard antioxidant activity screening [7] [8] |

| MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) | Cell culture tested (e.g., Sigma-Aldrich) | Colorimetric assay for cell viability and cytotoxic potential [4] |

| Cell Lines | Vero (kidney epithelial), H1299 (lung carcinoma) | In vitro models for assessing cytotoxicity and specific anticancer activity [4] |

| Enzymes for Inhibition | Acetylcholinesterase (AChE), α-Glucosidase | Molecular targets for neuroprotective and antidiabetic activity evaluation [8] |

| Reference Databases | NIST, Wiley, Adams mass spectral libraries | Critical for accurate identification of GC-MS components [4] [8] |

Essential oils represent a quintessential intersection of plant biochemistry and human application. Defined by their plant origin and method of extraction, their complex chemical nature is deciphered through sophisticated analytical techniques like GC-MS and HPLC. The subsequent evaluation of their bioactivity through a standardized suite of biochemical and cellular assays provides the scientific foundation for their use in pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and food science. As research progresses, the integration of advanced drug delivery systems to enhance the stability, bioavailability, and targeted delivery of these volatile compounds promises to further expand their therapeutic applications, solidifying their status as a vital resource in natural product development [5]. Future work will continue to focus on elucidating structure-activity relationships, understanding synergistic effects between components, and validating traditional uses through rigorous clinical investigation.

Essential oils, the complex volatile aromatic compounds produced by plants, are predominantly composed of terpenoids, the largest class of natural products with over 55,000 identified members [10] [11]. The structural diversity of these compounds—from the simple 5-carbon hemiterpenes to the complex 40-carbon tetraterpenes—originates from two universal 5-carbon precursors: isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) [10] [11]. The biosynthesis of these fundamental building blocks in plants occurs via two distinct, compartmentalized pathways: the mevalonate (MVA) pathway located in the cytoplasm and endoplasmic reticulum, and the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway operating within the plastids [12] [11]. This compartmentalization is not merely structural but functional, allowing plants to efficiently utilize different carbon sources and regulate the production of diverse terpenoid classes in response to environmental stimuli, such as light [11]. The coordinated operation of these pathways equips plants with a sophisticated chemical arsenal for defense, pollination, and communication, while also providing a treasure trove of compounds with significant applications in pharmaceuticals, nutraceuticals, fragrances, and biofuels [10] [11]. A fundamental understanding of the MVA and MEP pathways is therefore essential for research aimed at authentication, quality control, and biotechnological exploitation of plant essential oils.

Comparative Analysis of the MVA and MEP Pathways

The MVA and MEP pathways are evolutionarily distinct routes to the same isoprenoid precursors. They differ in their subcellular localization, initial substrates, enzymatic steps, energy cofactors, and the primary classes of terpenoids they supply.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of the MVA and MEP Pathways

| Feature | Mevalonate (MVA) Pathway | Methylerythritol Phosphate (MEP) Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Subcellular Localization | Cytoplasm, Endoplasmic Reticulum [11] | Plastids [11] |

| Initial Substrates | 3× Acetyl-CoA [11] | Pyruvate + Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GAP) [10] [11] |

| Key Intermediate | Mevalonate | Methylerythritol Phosphate (MEP) [10] |

| Energy Cofactors Consumed | 3 ATP, 2 NADPH [11] | 3 ATP, 3 NADPH [11] |

| Rate-Limiting Enzyme | HMG-CoA Reductase (HMGR) [11] | 1-Deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate Synthase (DXS) [11] |

| Primary Terpenoid Products | Sesquiterpenes (C15), Triterpenes (C30), Sterols [12] [11] | Monoterpenes (C10), Diterpenes (C20), Tetraterpenes (C40) [12] [11] |

| Distribution in Life Kingdoms | Eukaryotes, Archaea [10] | Most Bacteria, Algae, Higher Plants [10] [12] |

Table 2: Carbon Utilization and Output of the MVA and MEP Pathways

| Pathway | Carbon Input | Carbon Output | Pathway Committal Step |

|---|---|---|---|

| MVA Pathway | 3× Acetyl-CoA (2C) = 6 Carbon atoms [11] | IPP (C5) + CO₂ (C1) [11] | Conversion of HMG-CoA to Mevalonate by HMGR [11] |

| MEP Pathway | Pyruvate (3C) + GAP (3C) = 6 Carbon atoms [11] | IPP/DMAPP (C5) [11] | Conversion of DXP to MEP by MEP Synthase [10] |

Despite their compartmentalization, evidence from mutant analyses, chemical inhibition, and isotopic labeling studies indicates limited but regulated cross-talk between the MVA and MEP pathways, allowing for the formation of mixed-origin terpenoids [11]. The following diagrams illustrate the enzymatic sequences and regulatory nodes of these two core biosynthetic pathways.

Diagram 1: The Mevalonate (MVA) Pathway in the Cytoplasm

Diagram 2: The Methylerythritol Phosphate (MEP) Pathway in the Plastid

Experimental Approaches for Pathway Analysis

Investigating the activity, regulation, and inhibition of the MVA and MEP pathways requires a combination of biochemical, analytical, and molecular techniques. The following section details key experimental protocols used in foundational studies.

Protocol for Investigating Pathway Inhibition Using Radioactive Tracers

This protocol is adapted from a study investigating the hypolipidemic effects of Lippia alba essential oils on human cell lines, which specifically targeted the mevalonate pathway [13].

- Objective: To assess the inhibitory effect of a test compound (e.g., an essential oil or pure compound) on the synthesis of cholesterol and other lipids derived from the MVA pathway.

- Cell Culture and Treatment:

- Culture appropriate cell lines (e.g., human liver-derived HepG2 or non-liver A549 cells) under standard conditions (e.g., 37°C, 5% CO₂) [13].

- At a suitable confluence, treat cells with varying concentrations of the test compound (e.g., 3.2–32 µg/mL for L. alba essential oils) dissolved in an appropriate vehicle (e.g., DMSO, ethanol). Include vehicle-only controls and positive controls if available [13].

- Incubate for a predetermined time (e.g., 24 hours).

- Radioactive Labeling and Lipid Extraction:

- Pulse-label the cells with [¹⁴C]acetate, which acts as a universal precursor for acetyl-CoA and can be incorporated into lipids via the MVA pathway [13].

- After incubation, wash the cells to remove excess radiolabel.

- Lyse the cells and extract total lipids using a suitable organic solvent system (e.g., chloroform:methanol) [13].

- Lipid Analysis:

- Separation: Separate the different lipid classes (e.g., squalene, lanosterol, cholesterol, cholesteryl esters, triacylglycerols, phospholipids) using thin-layer chromatography (TLC) [13].

- Detection and Quantification: Visualize and quantify the radiolabeled lipids using a radioactivity scanner or by scintillation counting of scraped TLC spots. A reduction in the incorporation of [¹⁴C]acetate into specific intermediates (e.g., squalene, lanosterol, cholesterol) in treated cells compared to controls indicates inhibition of the MVA pathway [13].

- Downstream Analysis:

- Western Blot: Analyze the protein levels of key enzymes like HMG-CoA reductase (HMGCR) using Western blotting to determine if inhibition occurs via down-regulation of enzyme expression [13].

- Microscopy: Use fluorescence microscopy (e.g., with Nile Red stain) to analyze the size and volume of intracellular lipid droplets, which store neutral lipids like triacylglycerols and cholesteryl esters [13].

Protocol for Chemical Synthesis of MEP Pathway Intermediates

Access to pathway intermediates is crucial for enzyme mechanism studies, especially when biosynthesis or isolation is impractical. This is particularly relevant for the MEP pathway, which is a target for antimicrobial development [10].

- Objective: To chemically synthesize isotopically labeled or unlabeled intermediates of the MEP pathway, such as 1-deoxy-D-xylulose (DX), for use as enzyme substrates or analytical standards.

- Strategic Approach:

- The most widely used method involves using a protected D-threose scaffold to establish the correct stereochemistry [10].

- A key step is the introduction of the C-1 methyl group via a Grignard reaction (e.g., with methylmagnesium iodide), which is also the preferred method for incorporating isotopic labels (e.g., ¹³C, ²H) at this position [10].

- Synthetic Route (Representative):

- Starting Material: Begin with a protected form of D-threose, such as 2,4-O-benzylidene-D-threose [10].

- Grignard Addition: React the protected sugar with methylmagnesium iodide to introduce the methyl group and create a new carbon-carbon bond, yielding a mixture that requires separation of the desired threose isomer [10].

- Oxidation and Deprotection: Following separation, the intermediate is oxidized. The final deprotection step to yield the free sugar (1-deoxy-D-xylulose) can be achieved through methods like brominolysis of a distannylidene derivative [10].

- Purification and Validation: Purify the final product using standard chromatographic techniques. Validate the structure and purity using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and mass spectrometry (MS) [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Pathway Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function and Application in Research |

|---|---|

| [¹⁴C]Acetate or [¹³C]Acetate | A radioactive or stable isotopic tracer used to track the incorporation of carbon into terpenoids and lipids via the acetyl-CoA precursors of the MVA pathway [13]. |

| Cell Lines (e.g., HepG2, A549) | In vitro model systems derived from human tissues used to study pathway regulation, enzyme activity, and compound toxicity in a controlled environment [13]. |

| Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC) | An analytical technique for separating and visualizing different classes of lipids (e.g., sterols, triacylglycerols) from complex biological extracts [13]. |

| Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) | The primary analytical tool for separating, identifying, and quantifying the individual volatile components of an essential oil, crucial for authentication and metabolic profiling [12]. |

| Protected Sugar Scaffolds (e.g., D-threose) | Starting materials for the chemical synthesis of deoxy-sugar intermediates of the MEP pathway, such as 1-deoxy-D-xylulose, for enzymology studies [10]. |

| Enzyme Inhibitors (e.g., Statins, Fosmidomycin) | Pharmacological tools; Statins inhibit HMGCR in the MVA pathway, while Fosmidomycin inhibits DXR in the MEP pathway. Used to dissect pathway contributions [11]. |

| Specific Antibodies (e.g., anti-HMGCR) | Used in Western blotting and immunoassays to quantify protein expression levels of key regulatory enzymes in response to genetic or chemical perturbations [13]. |

Pathway Integration and Downstream Terpenoid Biosynthesis

The IPP and DMAPP produced by the MVA and MEP pathways serve as the universal five-carbon building blocks for all terpenoids. The assembly of these units into longer-chain prenyl diphosphates is catalyzed by a class of enzymes called isoprenyl diphosphate synthases (IDSs) [11]. These enzymes facilitate a "head-to-tail" condensation, where the "head" (diphosphate end) of one molecule is joined to the "tail" (unsaturated end) of another.

The initial condensation of one DMAPP and one IPP molecule, catalyzed by geranyl diphosphate synthase (GPPS), yields geranyl diphosphate (GPP, C10), the direct precursor of monoterpenes [10] [11]. The addition of another IPP to GPP by farnesyl diphosphate synthase (FPPS) forms farnesyl diphosphate (FPP, C15), the backbone of sesquiterpenes [11]. Further elongation by geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase (GGPPS) produces geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP, C20), the precursor for diterpenes [10] [11]. These linear prenyl diphosphates are then transformed into the immense structural diversity of the terpenoid family by terpene synthase (TPS) enzymes, which catalyze cyclization and rearrangement reactions, and further modified by enzymes like cytochrome P450 oxygenases (CYP450s) [11]. The following diagram summarizes this integrated network from primary precursors to major terpenoid classes.

Diagram 3: Assembly of Major Terpenoid Classes from IPP and DMAPP

Terpenes and terpenoids constitute one of the largest and most structurally diverse classes of natural products, with over 30,000 identified compounds [14]. These compounds serve as crucial biosynthetic building blocks in many organisms, particularly plants, where they mediate ecological interactions through defense against herbivores, attraction of pollinators, and inter-plant communication [14]. In recent decades, scientific interest in these compounds has expanded significantly due to their diverse pharmacological properties and alignment with global trends toward natural and sustainable products [15]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive examination of monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, and their oxygenated derivatives, focusing on their chemical classification, biosynthetic pathways, biological activities, and research methodologies relevant to plant essential oil chemistry.

Chemical Classification and Structure

Terpenes are fundamentally defined by their molecular architecture based on isoprene units (C5H8). The basic classification system depends on the number of these five-carbon building blocks incorporated into the carbon skeleton [14] [16].

Table 1: Classification of Terpenes Based on Isoprene Units

| Classification | Isoprene Units | Carbon Atoms | General Formula | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemiterpenes | 1 | C5 | C5H8 | Isoprene, angelic acid |

| Monoterpenes | 2 | C10 | C10H16 | Myrcene, limonene, pinene |

| Sesquiterpenes | 3 | C15 | C15H24 | Caryophyllene, humulene, farnesol |

| Diterpenes | 4 | C20 | C20H32 | Cafestol, kahweol, phytol |

| Sesterterpenes | 5 | C25 | C25H40 | - |

| Triterpenes | 6 | C30 | C30H48 | Squalene, lanosterol |

The term "terpene" traditionally refers to the hydrocarbon compounds consisting solely of carbon and hydrogen atoms, while "terpenoid" denotes terpenes that have undergone biochemical modifications through oxidation, resulting in the addition of functional groups containing oxygen [17] [14]. This oxidation process typically occurs after the formation of the carbon skeleton, leading to compounds with alcohol, aldehyde, ketone, ester, or other functional groups [18].

Monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes are particularly significant as they constitute the predominant volatile fractions of essential oils, with monoterpenes often comprising up to 90% of essential oil composition [19]. Monoterpenes (C10H16) consist of two isoprene units and are further subdivided into acyclic, monocyclic, and bicyclic structural types [17] [20]. Sesquiterpenes (C15H24) contain three isoprene units and display greater structural complexity, occurring as linear, cyclic, bicyclic, and tricyclic arrangements, including sesquiterpene lactones [21].

Biosynthetic Pathways

The biosynthesis of terpenes proceeds through two primary metabolic pathways that generate the universal five-carbon precursors isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and its isomer dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP) [14] [19].

The Mevalonate and Non-Mevalonate Pathways

The mevalonate (MVA) pathway operates primarily in the cytosol of archaea and eukaryotes, conjugating three molecules of acetyl CoA to produce IPP [14]. Conversely, the non-mevalonate (MEP) pathway, also known as the 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate pathway, occurs in plastids and utilizes pyruvate and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate as carbon sources [14]. The distribution of these pathways varies among organisms, with plants uniquely possessing both pathways operating in different cellular compartments [14].

Formation of Terpene Skeletons

Both biosynthetic pathways converge at the production of IPP and DMAPP. The enzyme isopentenyl pyrophosphate isomerase catalyzes the isomerization of IPP to DMAPP [14]. Subsequent chain elongation occurs through sequential head-to-tail condensation reactions:

- IPP + DMAPP → Geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP, C10) [monoterpene precursor]

- GPP + IPP → Farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP, C15) [sesquiterpene precursor]

- FPP + IPP → Geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP, C20) [diterpene precursor]

The enormous structural diversity of terpenes arises primarily from the action of terpene synthase enzymes, which convert these prenyl diphosphate precursors into the parent carbon skeletons of various terpenes, and cytochrome P450 enzymes that subsequently modify these skeletons through oxidation and rearrangement [14].

Diagram Title: Terpene Biosynthesis Pathways in Plants

Functional Groups and Chemical Properties

The biological activity and physicochemical properties of terpenes are profoundly influenced by their functional groups. Oxygen-containing functional groups transform non-polar hydrocarbons into more polar compounds with distinct chemical behaviors and biological activities [18].

Table 2: Functional Groups in Terpenoids and Their Properties

| Functional Group | Structure | Chemical Properties | Representative Terpenoids | Bioactive Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohols | -OH | Higher polarity, hydrogen bonding, increased water solubility | Linalool, geraniol, menthol | Calming effects, antimicrobial activity |

| Aldehydes | -CHO | Reactive, electrophilic, strong odors | Citral (geranial/neral) | Antimicrobial, antifungal properties |

| Ketones | C=O | Polar, hydrogen bond acceptors, thermally stable | Camphor, menthone, carvone | Cooling effects, digestive properties |

| Esters | -COOR | Pleasant aromas, less volatile, good stability | Linalyl acetate, geranyl acetate | Relaxing effects, flavoring applications |

| Phenols | Aromatic -OH | Acidic, strong antioxidants, antimicrobial | Carvacrol, thymol | Potent antimicrobial, antioxidant properties |

| Hydrocarbons | C-C and C-H only | Non-polar, volatile, low water solubility | Pinene, myrcene, limonene | Anti-inflammatory, solvent properties |

Terpene alcohols like linalool and geraniol demonstrate higher water solubility compared to their hydrocarbon counterparts due to their ability to form hydrogen bonds with water molecules [18]. Aldehydes such as citral exhibit strong electrophilic character, contributing to their antimicrobial efficacy through interaction with biological nucleophiles [18]. Ketones including camphor and menthone display greater thermal stability and serve as hydrogen bond acceptors, influencing their receptor interactions [18].

Biological Activities and Pharmacological Potential

Anti-Inflammatory Mechanisms

Terpenes and terpenoids demonstrate significant anti-inflammatory properties through multiple mechanisms, primarily via modulation of the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) signaling pathway [22]. This transcription factor regulates the expression of pro-inflammatory genes including cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6), enzymes (COX-2, iNOS), and adhesion molecules [22].

Specific terpenes including D-limonene, α-phellandrene, and α-pinene reduce the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in macrophage cell lines and animal models [22]. The sesquiterpene β-caryophyllene demonstrates particularly potent anti-inflammatory effects through activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) and subsequent inhibition of NF-κB signaling [17] [21]. Multiple terpenes additionally inhibit the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, reducing the activation of downstream effectors including extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and p38 [22].

Diagram Title: Terpene Modulation of Inflammatory Signaling

Antimicrobial Activities

Terpenes and terpenoids exhibit broad-spectrum antimicrobial properties against both antibiotic-susceptible and antibiotic-resistant bacteria [19]. Their mechanisms of action include disruption of microbial cell membranes, inhibition of protein synthesis, and interference with DNA replication [19]. Phenolic terpenoids such as carvacrol and thymol demonstrate particularly potent antibacterial activity against pathogens including Staphylococcus aureus [19]. The hydrophobicity of many terpenes enables them to partition into and disrupt lipid bilayers, increasing membrane permeability and causing leakage of cellular contents [19] [18].

Anticancer Properties

Monoterpenes like limonene and perillyl alcohol have demonstrated chemopreventive and therapeutic effects against various cancers in preclinical models [21]. These compounds act at both initiation and promotion/progression stages of carcinogenesis, with particular efficacy observed in mammary, liver, and lung cancer models [21]. Multiple monoterpenes induce apoptosis, inhibit cell proliferation, and promote differentiation in cancer cell lines [17]. Several terpenoids, including limonene and perillyl alcohol, have advanced to phase I clinical trials in patients with advanced cancers [21].

Experimental Methodologies

Extraction Techniques

The extraction of terpenes and terpenoids from plant material requires specialized techniques to preserve their volatile nature and chemical integrity. Standard methods include:

- Steam Distillation: The most common industrial method, where steam passes through plant material, vaporizing volatile compounds which are then condensed and separated [23].

- Hydrodistillation: Plant material is immersed in water during the distillation process, suitable for tougher plant tissues [23].

- Cold Pressing: Primarily used for citrus peels, employing mechanical pressure to release essential oils without thermal degradation [23].

- Solvent Extraction: Utilizes organic solvents like hexane or ethanol to extract terpenes, particularly effective for less volatile compounds [15].

- Supercritical Fluid Extraction: Employs supercritical CO₂ as a solvent, offering high selectivity and minimal thermal degradation [23].

- Microwave-Assisted Extraction: Uses microwave energy to accelerate distillation, reducing extraction time and improving yield [23].

Analysis and Characterization

Advanced analytical techniques are required to characterize complex terpene mixtures:

- Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS): The gold standard for terpene analysis, providing both separation and identification capabilities [23].

- FTIR Spectroscopy: Useful for functional group identification and quality verification [23].

- Organoleptic Evaluation: Sensory analysis to assess aroma profiles and detect adulteration [23].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Terpene Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| GC-MS System | Separation and identification of terpene compounds | High-resolution capillary columns (e.g., DB-5), electron impact ionization |

| Supercritical CO₂ Extraction System | Green extraction of terpenes | Pressures up to 1000 bar, temperatures 31-100°C, CO₂ purity ≥99% |

| - Steam Distillation Apparatus | Conventional extraction of essential oils | Glassware with volatile oil receiver, steam generator, condenser |

| FTIR Spectrometer | Functional group analysis | ATR attachment for liquid samples, spectral range 4000-400 cm⁻¹ |

| - Monoterpene Standards | Quantification and method validation | ≥95% purity, includes limonene, pinene, linalool, others |

| Sesquiterpene Standards | Quantification and method validation | ≥95% purity, includes caryophyllene, humulene, farnesene |

| - Cell Culture Models | In vitro bioactivity assessment | Macrophage lines (RAW 264.7), human chondrocytes, epithelial cells |

| ELISA Kits | Cytokine quantification | TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 measurements in cell supernatants |

| - Western Blot Reagents | Protein expression analysis | Antibodies for NF-κB, MAPK pathway components, iNOS, COX-2 |

Terpenes and terpenoids represent an exceptionally diverse class of natural compounds with significant potential for pharmaceutical and industrial applications. Their structural complexity, arising from varied carbon skeletons and functional group modifications, underpins their broad bioactivities including anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties. Continuing research into their mechanisms of action, therapeutic efficacy, and molecular targets will further elucidate their substantial potential in drug development and natural product chemistry. The integration of advanced extraction technologies with rigorous analytical methodologies will accelerate the discovery and application of these remarkable natural products in evidence-based medicine and sustainable technologies.

The phenylpropanoid pathway represents a foundational metabolic process in plants, responsible for generating an enormous array of aromatic secondary metabolites crucial to both plant survival and human applications. For researchers investigating the fundamentals of plant essential oil chemistry, understanding this pathway is paramount, as it contributes significantly to the volatile and bioactive compound profiles of numerous aromatic species [24] [25]. These compounds are synthesized from primary metabolites through the shikimate pathway, which is present in plants, fungi, and microorganisms but notably absent in animals, making phenylpropanoids exclusively plant-derived or microbially synthesized compounds [26] [27]. The biochemical gateway to phenylpropanoids begins with the aromatic amino acids L-phenylalanine and, in some monocots, L-tyrosine, which are themselves products of the shikimate pathway [26] [28]. Following their synthesis, these amino acids are deaminated by key enzymes such as phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) to initiate the dedicated phenylpropanoid biosynthetic machinery [29] [28].

In the context of essential oil research, phenylpropanoids contribute distinctive aromatic qualities, biological activities, and chemical stability to volatile extracts. While terpenoids constitute the majority of essential oil components, phenylpropanoids, though often less abundant, are critically important for their potent scent characteristics and significant pharmacological properties [24] [30]. These compounds typically contain a six-carbon aromatic phenyl group bonded to a three-carbon propene tail, forming the basic C6-C3 skeleton that characterizes this chemical family [28] [30]. The remarkable structural diversity observed among phenylpropanoids arises from efficient enzymatic modifications—including hydroxylation, methylation, acylation, glycosylation, and prenylation—of a limited set of core structures, leading to thousands of different naturally occurring derivatives [25] [30]. For drug development professionals, this chemical diversity translates to a broad spectrum of potential biological activities, positioning phenylpropanoids as promising candidates for therapeutic development.

Biochemical Origins: The Shikimate Pathway as the Aromatic Foundation

The shikimate pathway serves as the fundamental anabolic route through which plants, fungi, and microorganisms biosynthesize the basic aromatic building blocks for phenylpropanoid compounds. This seven-step metabolic process converts primary metabolites—phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) from glycolysis and erythrose-4-phosphate from the pentose phosphate pathway—into chorismate, the pivotal branch point intermediate for aromatic amino acid biosynthesis [26] [27]. The pathway's name derives from shikimic acid, a key intermediate first isolated from the Japanese star anise flower (Illicium anisatum) [26]. Notably, this pathway is absent in animals, rendering phenylalanine and tryptophan essential amino acids that must be acquired through diet and making the shikimate pathway an attractive target for herbicides and antimicrobial agents with minimal human toxicity [26] [27].

The enzymatic architecture of the shikimate pathway varies significantly across biological kingdoms. In bacteria, seven discrete monofunctional enzymes (often referred to as aro homologs) typically catalyze the sequential reactions. Plants typically employ six enzymes, including a bifunctional dehydroquinate dehydratase/shikimate dehydrogenase. Fungi and some protists, however, have evolved the AROM complex, a pentafunctional enzyme that catalyzes five consecutive reactions from 3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate (DAHP) to 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate (EPSP) [26]. This compartmentalization reflects the evolutionary adaptation of this essential pathway across different taxa. The pathway culminates with chorismate, which serves as the substrate for dedicated pathways producing the three aromatic amino acids: phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan [26]. For phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, phenylalanine serves as the primary precursor, though some plants utilize tyrosine via bifunctional phenylalanine/tyrosine ammonia-lyase (PTAL) enzymes [28].

Figure 1: The metabolic relationship between the shikimate pathway and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. The shikimate pathway converts primary metabolites into aromatic amino acids, with phenylalanine serving as the primary precursor for phenylpropanoid compounds through the action of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL).

Structural Diversity and Classification of Phenylpropanoids

Phenylpropanoids encompass a remarkable array of structurally diverse compounds, all sharing the characteristic C6-C3 skeleton but varying extensively in their functional group decorations and cyclic arrangements. In essential oil chemistry, these compounds are categorized primarily as non-terpenoid volatile constituents, though their chemical complexity extends well beyond simple volatile structures [24] [30]. The wonderful structural diversity of phenylpropanoids arises from efficient enzymatic modification of a limited set of core structures, including hydroxylation, methylation, glycosylation, acylation, and cyclization reactions that occur at various stages along the biosynthetic pathway [25] [30].

The classification of phenylpropanoids in essential oils typically follows their functional groups and skeletal arrangements:

Simple Phenylpropanes and Phenol Derivatives

These compounds retain the basic propane side chain with varying degrees of oxidation and substitution on the aromatic ring. Representative examples include:

- Eugenol (4-allyl-2-methoxyphenol): A major constituent of clove oil, noted for its antiseptic and analgesic properties

- Chavicol (4-allylphenol): Found in betel leaf oil

- Estragole (4-allylanisole): Characteristic component of tarragon and basil oils

- Safrole (4-allyl-1,2-methylenedioxybenzene): Principal component of sassafras oil

- * trans-Anethole* (1-methoxy-4-(1-propenyl)benzene): Major constituent of anise and fennel oils [24] [30]

Phenylpropenes

These compounds feature a propenyl (rather than allyl) side chain and include:

- Isoeugenol (2-methoxy-4-(1-propenyl)phenol): Found in ylang-ylang and nutmeg oils

- * trans-Cinnamaldehyde*: The characteristic compound of cinnamon bark oil [30]

Cinnamic Acid Derivatives and Esters

These include hydroxylated and methoxylated cinnamic acids and their esters:

- Cinnamic acid: The initial product of phenylalanine deamination

- Coumaric acid, Caffeic acid, Ferulic acid, Sinapic acid: Hydroxylated and methoxylated derivatives

- Ethyl cinnamate: A common volatile ester contributing to fruity and balsamic aromas [28]

Table 1: Major Phenylpropanoid Classes in Essential Oils and Their Characteristics

| Class | Representative Compounds | Plant Sources | Volatility | Bioactivities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allyl-/Propenyl-benzenes | Eugenol, Safrole, Estragole, trans-Anethole | Clove, Sassafras, Tarragon, Anise | High | Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, Anesthetic |

| Cinnamaldehydes | Cinnamaldehyde | Cinnamon bark | Moderate to High | Antimicrobial, Anti-inflammatory, Blood Glucose Regulation |

| Cinnamic Acid Esters | Ethyl cinnamate, Methyl cinnamate | Strawberry, Basil | Moderate | Flavoring, Fragrance, Antioxidant |

| Phenylpropanoid-related Benzenoids | Vanillin | Vanilla bean | Low to Moderate | Flavoring, Antioxidant |

The structural complexity of phenylpropanoids directly influences their volatility, aroma profile, and biological activity. For instance, the presence of methoxy groups (as in eugenol and estragole) typically enhances antimicrobial potency, while the aldehyde functionality in cinnamaldehyde contributes to both its characteristic aroma and significant biological activity [24] [30]. Understanding these structure-activity relationships is crucial for drug development professionals seeking to harness phenylpropanoids for therapeutic applications.

Biosynthetic Pathway: From Phenylalanine to Complex Phenylpropanoids

The biosynthesis of phenylpropanoids proceeds through a carefully orchestrated series of enzymatic transformations that convert phenylalanine into diverse aromatic compounds. This pathway branches extensively, generating numerous metabolic routes that often operate in a tissue-specific, developmentally regulated, and environmentally responsive manner [29] [25]. The initial and committed step in phenylpropanoid biosynthesis is the deamination of phenylalanine to form cinnamic acid, catalyzed by the pivotal enzyme phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) [29] [28]. In some plants, particularly grasses, a bifunctional phenylalanine/tyrosine ammonia-lyase (PTAL) can utilize both aromatic amino acids as substrates [28].

Following the formation of cinnamic acid, a series of cytochrome P450-dependent monooxygenases introduce hydroxyl groups at specific positions on the aromatic ring. Cinnamate 4-hydroxylase (C4H) catalyzes the para-hydroxylation of cinnamic acid to yield p-coumaric acid, which then undergoes activation to its coenzyme A thioester (p-coumaroyl-CoA) via 4-coumarate:CoA ligase (4CL) [29] [28]. This activated intermediate serves as the central branch point from which multiple specialized pathways diverge. Subsequent hydroxylation and methylation reactions, mediated by enzymes such as p-coumarate 3-hydroxylase (C3H), caffeic acid O-methyltransferase (COMT), and caffeoyl CoA O-methyltransferase (CCoAOMT), generate the methoxylated precursors for various phenylpropanoid subclasses [29].

The pathway further diversifies through side-chain modifications, including reductions catalyzed by hydroxycinnamoyl-CoA reductase (CCR) and hydroxycinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase (CAD), which convert activated CoA esters into the monolignol precursors of lignin and suberin [29]. For the production of volatile phenylpropenes such as eugenol and isoeugenol, specific reductases and methyltransferases act on activated intermediates. Meanwhile, the entry into flavonoid biosynthesis occurs when p-coumaroyl-CoA combines with three molecules of malonyl-CoA in a reaction catalyzed by chalcone synthase (CHS), producing naringenin chalcone, the precursor to all flavonoids [28]. This complex biosynthetic network demonstrates the remarkable plasticity of plant metabolism in generating chemical diversity from a limited set of core reactions.

Figure 2: Key branching pathways in phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. The core pathway diverges to produce multiple compound classes, including monolignols for lignin formation, volatile phenylpropenes, and flavonoids. Enzyme abbreviations: PAL (phenylalanine ammonia-lyase), C4H (cinnamate 4-hydroxylase), 4CL (4-coumarate:CoA ligase), C3H (p-coumarate 3-hydroxylase), HCT (hydroxycinnamoyl transferase), COMT (caffeic acid O-methyltransferase), F5H (ferulate 5-hydroxylase), CCR (cinnamoyl-CoA reductase), CAD (cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase), CHS (chalcone synthase), CHI (chalcone isomerase), EGS (eugenol synthase).

Analytical Methodologies for Phenylpropanoid Research

Advanced analytical techniques are essential for elucidating the complex chemical profiles and biosynthetic pathways of phenylpropanoids in plant essential oils. Contemporary research employs a multi-omics approach, integrating metabolomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic analyses to comprehensively characterize these compounds and their regulation [31] [32]. The analytical workflow typically begins with optimized extraction methods suitable for volatile and semi-volatile phenylpropanoids, followed by sophisticated separation and detection techniques, and culminates in data integration and pathway analysis.

Extraction Protocols for Volatile Phenylpropanoids

The extraction of phenylpropanoids from plant material for essential oil analysis primarily employs steam distillation and hydrodistillation techniques, which effectively preserve the volatile nature of these compounds [24]. For more sensitive analyses that aim to capture a broader chemical spectrum, including oxygenated derivatives, solid-phase microextraction (SPME) and supercritical fluid extraction (SFE) offer enhanced sensitivity and reduced artifact formation. The extraction solvent must be carefully selected based on the chemical properties of target phenylpropanoids; for instance, methanol and methanol-water mixtures have demonstrated high efficiency for extracting a wide range of phenolic compounds, including flavonoid derivatives, from plant tissues [32]. Following extraction, purification steps such as liquid-liquid partitioning and solid-phase extraction may be employed to remove interfering compounds and concentrate analytes of interest prior to instrumental analysis.

Separation and Detection Techniques

Gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (GC-MS) represents the gold standard for analyzing volatile phenylpropanoids in essential oils, providing excellent separation efficiency and reliable identification through mass spectral libraries [24]. For less volatile or thermally labile phenylpropanoids (such as glycosylated derivatives or hydroxycinnamic acid esters), ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) coupled with photodiode array detection and mass spectrometry (UPLC-PDA-MS) offers superior analytical capabilities [32]. The high resolution and sensitivity of modern UPLC systems enable the separation of complex mixtures of phenolic compounds within short analysis times, while tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) provides structural elucidation through fragmentation patterns. Quantitative analysis typically employs external calibration curves with authentic standards when available, or semi-quantitative analysis using representative compounds for compound classes.

Metabolite Profiling and Quantitation

For comprehensive phenylpropanoid analysis, targeted and untargeted metabolomic approaches are employed. Targeted methods focus on specific compound classes using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) for enhanced sensitivity, while untargeted approaches aim to capture the entire chemical landscape through high-resolution mass spectrometry [32]. In recent studies, total phenolic content is frequently determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu method expressed as gallic acid equivalents (GAE), while total flavonoid content is measured using aluminum chloride-based assays expressed as catechin equivalents (CAE) [32]. Antioxidant capacity assessments through ABTS, DPPH, and FRAP assays provide functional correlates to phenylpropanoid composition, with results typically expressed as Trolox equivalents (TE) [32]. These quantitative measures allow researchers to compare phenylpropanoid abundance and bioactivity across different plant genotypes, tissues, and growth conditions.

Table 2: Key Analytical Methods for Phenylpropanoid Characterization in Essential Oil Research

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Applications in Phenylpropanoid Research | Key Metrics/Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extraction | Steam Distillation, Hydrodistillation, SPME, Solvent Extraction (Methanol, Ethyl Acetate) | Isolation of volatile and semi-volatile phenylpropanoids from plant material | Extraction Yield, Chemical Profile Preservation |

| Separation | GC, UPLC/HPLC | Separation of complex phenylpropanoid mixtures prior to detection | Resolution, Retention Time, Peak Shape |

| Detection & Identification | GC-MS, LC-PDA-MS, HRMS/MS | Compound identification, structural elucidation, purity assessment | Mass Spectra, UV-Vis Spectra, Fragmentation Patterns, Accurate Mass |

| Quantitation | External Standard Calibration, Standard Addition, Internal Standard Methods | Determination of phenylpropanoid concentrations in samples | Concentration Values, Linearity, Detection Limits |

| Functional Assays | ABTS, DPPH, FRAP, ORAC | Assessment of antioxidant capacity correlated with phenylpropanoid content | IC50 Values, Trolox Equivalents, % Inhibition |

Regulation of Phenylpropanoid Biosynthesis: Transcriptional Control and Multi-Omics Insights

The phenylpropanoid pathway is subject to sophisticated regulatory control at multiple levels, with transcriptional regulation playing a predominant role in determining the timing, tissue specificity, and amplitude of phenylpropanoid production. Recent advances in multi-omics technologies have significantly enhanced our understanding of these regulatory mechanisms, particularly through the integration of transcriptomic and metabolomic data [31] [32]. Transcription factors from the MYB, bZIP, WRKY, and HD-Zip families have been identified as key regulators of phenylpropanoid biosynthetic genes, with many exhibiting binding specificity to the AC-rich promoter elements commonly found in phenylpropanoid pathway genes [29].

Among these transcriptional regulators, R2R3-MYB transcription factors have emerged as particularly important master switches controlling various branches of the phenylpropanoid pathway. In chickpea (Cicer arietinum), for instance, subgroup 7 MYB factors such as CaMYB39 have been shown to activate the transcription of multiple flavonoid biosynthetic genes, including chalcone synthase (CHS), chalcone isomerase (CHI), flavanone 3-hydroxylase (F3H), and flavonol synthase (FLS), leading to increased flavonol production [32]. Similarly, subgroup 5 MYB transcription factors (CaPAR1/CaMYB89 and CaPAR2/CaMYB98) regulate proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in seed coats, while subgroup 6 MYBs (CaLAP1 and CaLAP2) control anthocyanin production [32]. These findings demonstrate how different MYB subgroups coordinate specific branches of the phenylpropanoid pathway, enabling the targeted production of distinct compound classes.

Multi-omics approaches have proven particularly powerful in elucidating these regulatory networks. In poplar species challenged with the canker pathogen Cytospora chrysosperma, comparative transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses revealed precise activation of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis in resistant species, with coordinated upregulation of PAL, C4H, 4CL, and other pathway genes corresponding to increased accumulation of defensive phenylpropanoids [31]. Similarly, in developing chickpea seeds, the expression levels of MYB transcription factors (CaMYB39, MYB111-like, and CaMYB92) and phenylpropanoid biosynthetic genes (PAL, CHI, and CHS) showed strong positive correlation with the accumulation of total phenolics, total flavonoids, and specific flavonols (myricetin, quercetin, kaempferol, and isorhamnetin), as well as with antioxidant capacity [32]. These integrative studies demonstrate how plants fine-tune phenylpropanoid production in response to developmental cues and environmental challenges, providing a molecular basis for the observed metabolic diversity.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Phenylpropanoid Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Inhibitors | Glyphosate (EPSP synthase inhibitor), AIP (PAL inhibitor), Specific cytochrome P450 inhibitors | Pathway perturbation studies, Elucidation of metabolic flux | Glyphosate specifically targets the shikimate pathway, affecting phenylpropanoid precursor supply [26] |

| Analytical Standards | Authentic phenylpropanoid standards (eugenol, cinnamaldehyde, trans-anethole, caffeic acid, ferulic acid, etc.) | Compound identification and quantification, Calibration curves | Commercial availability varies; some compounds require synthesis in-house [32] |

| RNAi/Knockout Lines | PAL-deficient transgenic plants, MYB transcription factor knockouts | Functional gene validation, Study of regulatory mechanisms | May exhibit pleiotropic effects due to pathway centrality [29] |

| Heterologous Expression Systems | E. coli, Yeast, Tobacco expression of phenylpropanoid enzymes | Enzyme characterization, Metabolic engineering | Useful for producing specific phenylpropanoids or pathway intermediates [27] |

| Multi-omics Databases | Transcriptomic datasets, Metabolomic libraries, Gene co-expression networks | Systems biology approaches, Gene discovery | Integration required for comprehensive pathway understanding [31] [32] |

Phenylpropanoids represent a chemically diverse and biologically significant class of plant specialized metabolites with profound implications for essential oil chemistry and drug development research. Their biosynthetic origin from the shikimate pathway places them at the intersection of primary and specialized metabolism, with structural diversity arising from enzymatic modifications of a core phenylpropane skeleton. Current research employing multi-omics approaches continues to unravel the complex regulatory networks that control phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, revealing sophisticated transcriptional programs orchestrated by MYB and other transcription factor families. For drug development professionals, these compounds offer promising therapeutic potential due to their diverse bioactivities, including antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anticancer properties.

Future research directions will likely focus on harnessing this knowledge for metabolic engineering applications, both in plant systems and microbial hosts. The identification of key transcription factors such as CaMYB39 that regulate entire pathway branches presents opportunities for manipulating phenylpropanoid profiles to enhance desired compounds [32]. Similarly, the integration of multi-omics data across different plant species and experimental conditions will facilitate the identification of additional regulatory nodes and rate-limiting steps in phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. For essential oil chemistry specifically, understanding the factors that control the partitioning between volatile and non-volatile phenylpropanoid derivatives will be crucial for optimizing the production of these economically and therapeutically valuable compounds. As analytical technologies continue to advance and our fundamental knowledge of plant metabolism deepens, phenylpropanoids will undoubtedly remain a rich area of investigation at the frontier of plant essential oil research.

Within the framework of plant essential oil chemistry research, understanding that the extracted oil is not always a perfect mirror of the plant's native volatile compounds is a fundamental principle. The extraction method itself is not a passive recovery tool but an active participant that can introduce artifacts and significantly influence the chemical profile of the final product [33]. These method-induced variations can alter biological activities, impact therapeutic efficacy, and challenge the reproducibility of scientific studies [34]. This whitepaper provides a technical examination of how different extraction techniques dictate the chemical composition of essential oils, offering researchers and drug development professionals a guide to critical methodological considerations.

Conventional vs. Modern Extraction Techniques

The choice of extraction technique profoundly affects the yield, composition, and bioactivity of essential oils. These methods can be broadly categorized into conventional and modern approaches, each with distinct mechanisms and impacts on the final product.

Conventional Methods

Hydrodistillation (HD) and Steam Distillation (SD) are the most widely used conventional methods. In HD, plant material is fully immersed in boiling water, while in SD, steam is passed through the plant matrix. Although robust and widely accepted, these methods involve prolonged exposure to heat and water, which can lead to hydrolysis, thermal degradation, or oxidation of sensitive compounds [35] [36]. For instance, monoterpenes are particularly susceptible to chemical changes under these conditions [34]. Solvent extraction is another conventional technique, but it often co-extracts non-volatile components like fats and waxes, requiring additional purification steps and risking solvent residue in the final product [36] [34].

Modern Green Methods

Modern techniques aim to overcome the limitations of conventional methods by improving efficiency, selectivity, and sustainability.

- Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE), particularly using CO₂, operates at controllable temperatures and pressures, minimizing thermal degradation [35] [33]. It is highly selective, does not leave solvent residues, and is effective for extracting heat-sensitive components [34].

- Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) and related methods like microwave hydrodiffusion and gravity use microwave energy to heat the internal water within plant cells, causing them to rupture and release essential oils rapidly [34]. This approach significantly reduces extraction time and energy consumption compared to conventional distillation [35] [37].

- Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME) is a solvent-free, fully automatable technique that is highly sparing to sensitive components. It is particularly useful for analyzing the genuine aroma profile of plants without inducing thermal artifacts [36].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Essential Oil Extraction Methods

| Extraction Method | Key Mechanism | Typical Yield | Risk of Artifacts | Major Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrodistillation (HD) | Plant material boiled in water | Varies by plant material | High (hydrolysis, thermal degradation) | Simple apparatus, widely used | Prolonged heating, acidic conditions |

| Steam Distillation (SD) | Steam volatilizes essential oils | Varies by plant material | Moderate to High | Cost-effective, industrially established | Loss of water-soluble & highly volatile compounds |

| Solvent Extraction | Uses organic solvents (hexane, ethanol) | High (includes resins) | Moderate (solvent residues) | Effective for heat-sensitive compounds | Co-extraction of non-aroma-active compounds (waxes, pigments) |

| Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) | Uses supercritical CO₂ as solvent | Highly tunable yield | Very Low | Tunable selectivity, no solvent residue, low thermal stress | High initial equipment cost |

| Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) | Microwave energy heats internal water | High (efficient) | Low | Rapid, low energy input, high purity | Requires plant material with sufficient moisture |

| Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME) | Adsorption onto a coated fiber | N/A (analytical scale) | Very Low | No solvent, preserves genuine profile, automatable | Limited to analytical applications |

Analytical Methodologies for Characterizing Extracts

Rigorous analytical techniques are essential for identifying the chemical alterations induced by different extraction processes. The combination of multiple techniques provides the highest confidence in compound identification.

Gas Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS)

Gas Chromatography (GC) coupled with Mass Spectrometry (MS) is the cornerstone of essential oil analysis [34]. GC separates the complex mixture, while MS provides fragmentation patterns for tentative identification of individual components. Critical parameters that must be reported include the column type and size, carrier gas flow rate, and temperature programming parameters (injector, detector, and column temperatures) [34]. The use of retention indices (RI), calculated against a homologous series of n-alkanes, is crucial for comparing data across different laboratories and instruments [34].

Planar Chromatography and NMR

While GC/MS is dominant, Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC) remains a rapid and inexpensive reference method in various pharmacopoeias [38]. Modern planar techniques like Automated Multiple Development (AMD) and Optimum Performance Laminar Chromatography (OPLC) offer superior separations; for example, OPLC can cleanly separate the phenol isomers thymol and carvacrol, which is valuable for chemotype identification [38].

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy provides complementary information to MS. While MS excels at identification, NMR is powerful for elucidating molecular structures and confirming isomer identities. A Statistical Total Correlation (STOCSY) approach can be used to fuse data from GC-MS and NMR, leading to higher confidence in compound identification by statistically correlating signals from the two analytical platforms [39].

Experimental Protocol: GC-MS Analysis of Thyme Essential Oils

1. Sample Preparation: Essential oils are obtained via HD, SD, or SFE. The oil is dissolved in a suitable volatile solvent (e.g., hexane or dichloromethane) at a known concentration (e.g., 1% w/v) and filtered through a 0.22 µm membrane prior to injection [38].

2. GC-MS Instrumentation and Conditions:

- GC System: Equipped with a split/splitless injector.

- Column: Fused silica capillary column (e.g., 30 m x 0.25 mm i.d., coated with 5% phenyl polysiloxane, film thickness 0.25 µm).

- Carrier Gas: Helium, constant flow rate of 1.0 mL/min.

- Injection: Split mode (split ratio 1:50), injection volume 1.0 µL, injector temperature 250°C.

- Oven Temperature Program: Initial temperature 60°C (hold 1 min), ramp to 220°C at 3°C/min, then to 280°C at 10°C/min (hold 5 min).

- MS Detection: Electron Impact (EI) ionization at 70 eV; ion source temperature 230°C; mass scan range 40-400 m/z.

3. Data Analysis: Constituents are identified by comparing their mass spectra with commercial libraries (e.g., NIST, Wiley) and by calculating their Retention Indices relative to a co-injected n-alkane series (C8-C40) [34] [38]. Confirmation should be done by injection of authentic standards where available.

Documented Chemical Variations and Induced Artifacts

The interaction between the extraction process and the plant matrix leads to measurable changes in the oil's chemical signature, ranging from shifts in dominant compounds to the creation of new artifacts.

Method-Dependent Profile Changes

Different extraction methods can significantly alter the chemical profile of the same plant species. A study on rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) demonstrated that Microwave-assisted Distillation (MD) yielded oils with the highest enrichment of oxygenated monoterpenes (up to 59.6%) compared to HD and SD, particularly in oils harvested during the spring [37]. This highlights the combined influence of season and technique. Furthermore, SPME has been shown to provide a more accurate representation of the genuine aroma compounds in plants like marjoram and thyme because it minimizes thermal degradation, unlike HD [36].

Formation of Artifacts

Artifact formation is a critical concern. During hydrodistillation, acidic conditions and high temperatures can trigger hydrolysis and oxidation [36]. A classic example is the transformation of monoterpene alcohols or aldehydes under harsh conditions. For instance, the genuine plant constituent linalool can dehydrate to form myrcene, or its oxide can form, altering the oil's fragrance and bioactivity. Similarly, cis-rose oxide can be artifactually formed from citronellol during distillation [34]. Solvent extraction, while avoiding heat, can lead to contamination from solvent residues and co-extraction of unwanted waxes and pigments [34].

Table 2: Documented Chemical Variations and Artifacts in Selected Essential Oils

| Plant Species | Extraction Method | Observed Chemical Shifts & Artifacts | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rosmarinus officinalis (Rosemary) | Microwave-Assisted Distillation (MD) vs. Hydrodistillation (HD) | Higher proportion of oxygenated monoterpenes (e.g., 1,8-Cineole, Camphor) in MD vs. HD [37]. | Alters antioxidant capacity and potential therapeutic value. |

| Origanum majorana (Marjoram), Thymus vulgaris (Thyme) | Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME) vs. Hydrodistillation (HD) | SPME captures a more genuine profile; HD causes discrimination and transformation of thermally sensitive compounds [36]. | Challenges the accuracy of the reported natural composition when using HD. |

| General Plant Material | Steam Distillation (SD) / Hydrodistillation (HD) | Loss of water-soluble compounds (e.g., phenols) and highly volatile components [34]. | Incomplete chemical profile and potential underestimation of bioactivity. |

| General Plant Material | Solvent Extraction | Co-extraction of non-aroma-active compounds (fats, waxes, pigments) [36]. | Requires additional purification steps; can taint extracts for food/fragrance. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful essential oil research requires specific reagents and materials to ensure analytical accuracy and reproducibility.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Clevenger or Dean-Stark Apparatus | Standard glassware for laboratory-scale hydrodistillation or steam distillation. | Used for determining essential oil content as per pharmacopoeial methods [34]. |

| n-Alkane Standard Mixture (C8-C40) | Used for calculating Kováts Retention Indices (RI) in GC analysis. | Critical for reliable cross-laboratory compound identification [34]. |

| Authentic Reference Standards (e.g., Thymol, Carvacrol, Linalool) | Used for definitive confirmation of compound identity by matching retention time and mass spectrum. | Commercially available from suppliers like Extrasynthèse [38]. |

| Deuterated Chloroform (CDCl₃) | Standard solvent for NMR analysis of essential oils. | Provides a deuterium lock for stable NMR measurements [39]. |

| HPTLC Plates (e.g., silica gel, CN, NH₂) | Used for modern planar chromatographic analysis (TLC, OPLC, AMD). | Enable high-resolution separation of complex essential oil mixtures [38]. |

| SPME Fibers (various coatings) | For solvent-free sampling of volatile compounds for GC-MS. | Coating selection (e.g., PDMS, CAR/PDMS) is critical for analyte selectivity [36]. |

The path from plant to essential oil is paved with chemical decisions dictated by the extraction methodology. The evidence is clear that techniques like supercritical fluid extraction and microwave-assisted methods often provide superior outcomes in terms of yield and fidelity to the plant's genuine chemical profile, yet the optimal choice is inherently defined by the research or development goals [35] [33]. A deep understanding of these artifacts and variations is not merely an analytical concern but a foundational aspect of producing reliable, efficacious, and reproducible essential oil-based products. Future research must continue to refine green extraction techniques and develop integrated analytical workflows to fully elucidate and control the complex chemistry of these valuable natural products.

From Plant to Molecule: Analysis, Pharmacological Actions, and Therapeutic Mechanisms

Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) stands as a cornerstone analytical technique in plant essential oil chemistry research, providing researchers and pharmaceutical development professionals with unparalleled capability to characterize complex volatile mixtures. This combined system separates complex samples into individual components and provides definitive identification, making it indispensable for quality control, authentication, and bioactivity assessment of plant-derived substances [24]. The technique's exceptional sensitivity and specificity for volatile and semi-volatile organic compounds perfectly match the chemical nature of essential oils, which are predominantly composed of terpenes and phenylpropanoids [24] [40]. As the field of phytomedicine continues to gain prominence in drug discovery, robust analytical methods like GC-MS provide the critical foundation for standardizing plant-based substances and understanding their pharmacological potential [41].

Core Principles of GC-MS Technology

Instrumentation and Operational Mechanics

The power of GC-MS stems from the synergistic combination of two powerful analytical techniques:

Gas Chromatograph (GC): The sample is vaporized and introduced into a capillary column coated with a stationary phase. An inert carrier gas (e.g., helium, hydrogen) moves the sample through the column. Separation occurs as different compounds interact differently with the stationary phase, causing them to elute at distinct retention times based on their boiling points and polarities [42].

Mass Spectrometer (MS): As components elute from the GC column, they enter the mass spectrometer where they are ionized and fragmented. The resulting ions are separated based on their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) and detected, producing a mass spectrum for each compound [42].

This dual-separation and identification system makes GC-MS exceptionally powerful; while GC alone cannot definitively identify co-eluting compounds, and MS alone struggles with complex mixtures, their combination provides high-confidence identifications [43].

Ionization Techniques for Essential Oil Analysis

The ionization method chosen significantly impacts the structural information obtained:

Electron Ionization (EI): The most common technique, employing 70 eV electrons to bombard molecules, causing reproducible fragmentation. This "hard ionization" generates extensive fragment patterns ideal for library matching against extensive databases like NIST [43]. Most essential oil studies utilize EI for its reproducible mass spectra [44] [41].

Chemical Ionization (CI): A "softer" technique that uses reagent gases to produce ions with less fragmentation, often preserving the molecular ion. This is particularly valuable for confirming molecular weights when studying new or unknown compounds [43].

Table 1: Comparison of GC-MS Ionization Techniques

| Technique | Mechanism | Fragmentation | Primary Application in Essential Oil Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electron Ionization (EI) | 70 eV electron bombardment | Extensive fragmentation | Library-based identification of known compounds |

| Chemical Ionization (CI) | Ion-molecule reactions with reagent gas | Minimal fragmentation | Molecular weight determination of unknown compounds |

Experimental Design and Methodologies

Sample Preparation Techniques for Essential Oils

Proper sample preparation is critical for accurate GC-MS analysis of plant essential oils:

Extraction Methods: Hydrodistillation, steam distillation, and mechanical expression (for citrus peels) are standard methods for obtaining essential oils from plant material [24]. The extraction method significantly impacts oil composition and must be consistently reported.

Sample Introduction: For liquid essential oil samples, direct injection (typically 0.1-1 µL) using sophisticated autosamplers provides precision. For analyzing volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from plant material directly, Purge and Trap (P&T) systems can concentrate headspace vapors for enhanced sensitivity [43].

Solvent Selection: Appropriate solvents (often hexane, dichloromethane, or methanol) must be chosen based on solubility, volatility, and chromatographic compatibility. Sample dilution is frequently necessary to avoid column overloading and detector saturation [45].

GC-MS Analysis Workflow for Essential Oils

The following workflow diagram illustrates a standardized approach for essential oil analysis:

Method Validation Parameters

For pharmaceutical applications, GC-MS methods must be rigorously validated. Key parameters include [41]:

- Specificity: Ability to unequivocally identify analytes in complex mixtures

- Linearity: Response proportionality across concentration ranges (R² > 0.999)

- Accuracy: Agreement between measured and true values (typically 98-102%)

- Precision: Repeatability and reproducibility (RSD ≤ 2.5%)

Data Processing and Compound Identification

Spectral Interpretation and Library Matching

Modern GC-MS data processing involves sophisticated software tools for:

Spectral Deconvolution: Automated algorithms separate co-eluting compounds and extract pure mass spectra, essential for complex essential oil profiles [46].

Library Searching: Experimental mass spectra are compared against reference libraries (NIST, Wiley) using matching algorithms. The NIST library contains over 300,000 spectra, making it an invaluable resource for terpene identification [47].