Plant Chemical Ecology: A Foundational Guide for Drug Discovery and Sustainable Agriculture

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive introduction to plant chemical ecology.

Plant Chemical Ecology: A Foundational Guide for Drug Discovery and Sustainable Agriculture

Abstract

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive introduction to plant chemical ecology. It explores the foundational principles of plant-derived secondary metabolites and their ecological roles, details cutting-edge methodological approaches for discovery and application, addresses common challenges in translation and optimization, and presents validation frameworks for comparing bioactivity. By integrating ecological theory with pharmaceutical and agricultural applications, this article serves as a strategic resource for leveraging plant chemical diversity in the development of novel therapeutics and sustainable pest management solutions.

The Language of Plants: Unlocking the Diversity and Functions of Secondary Metabolites

Defining Plant Chemical Ecology and Its Core Principles

Plant chemical ecology is an interdisciplinary field that studies the chemical-mediated interactions between plants and other organisms, including insects, microbes, and other plants, as well as the role of these chemicals in plant adaptation to the environment [1] [2]. These interactions are facilitated by a diverse array of secondary metabolites—chemical compounds not directly involved in primary plant growth or development—which function as signals, defenses, and mediators of complex ecological relationships [1]. The field has evolved from fundamental discoveries to applied strategies in sustainable agriculture and integrated pest management (IPM) [3].

Core Principles of Plant Chemical Ecology

The foundational concepts of plant chemical ecology can be summarized through several core principles, which are detailed in the table below.

Table 1: Core Principles of Plant Chemical Ecology

| Principle | Description | Key Concepts |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Defense | Plants produce secondary metabolites to protect against herbivores and pathogens [1]. | Induced and constitutive defenses; toxicity; antinutritive effects [1] [2]. |

| Tritrophic Interactions | Plant volatiles can attract natural enemies of herbivores, creating a defense cascade across three trophic levels [1]. | Herbivore-induced plant volatiles (HIPVs); parasitoid and predator attraction [1] [3]. |

| Allelopathy | Plants release biochemicals into the environment to inhibit the growth or germination of competing plant species [1] [4]. | Interference competition; soil chemical ecology; root exudation [1]. |

| Plant-Pollinator Communication | Floral scents and colors guide pollinators, ensuring reproductive success [3]. | Volatile organic compounds (VOCs); pollinator specificity; mutualism [3]. |

| Dynamic and Inducible Responses | Chemical production is not static; it can be induced or modulated by environmental cues, such as herbivore attack [1]. | Signal transduction; priming; cost of defense; phenotypic plasticity [1]. |

Key Chemical Classes and Signaling Pathways

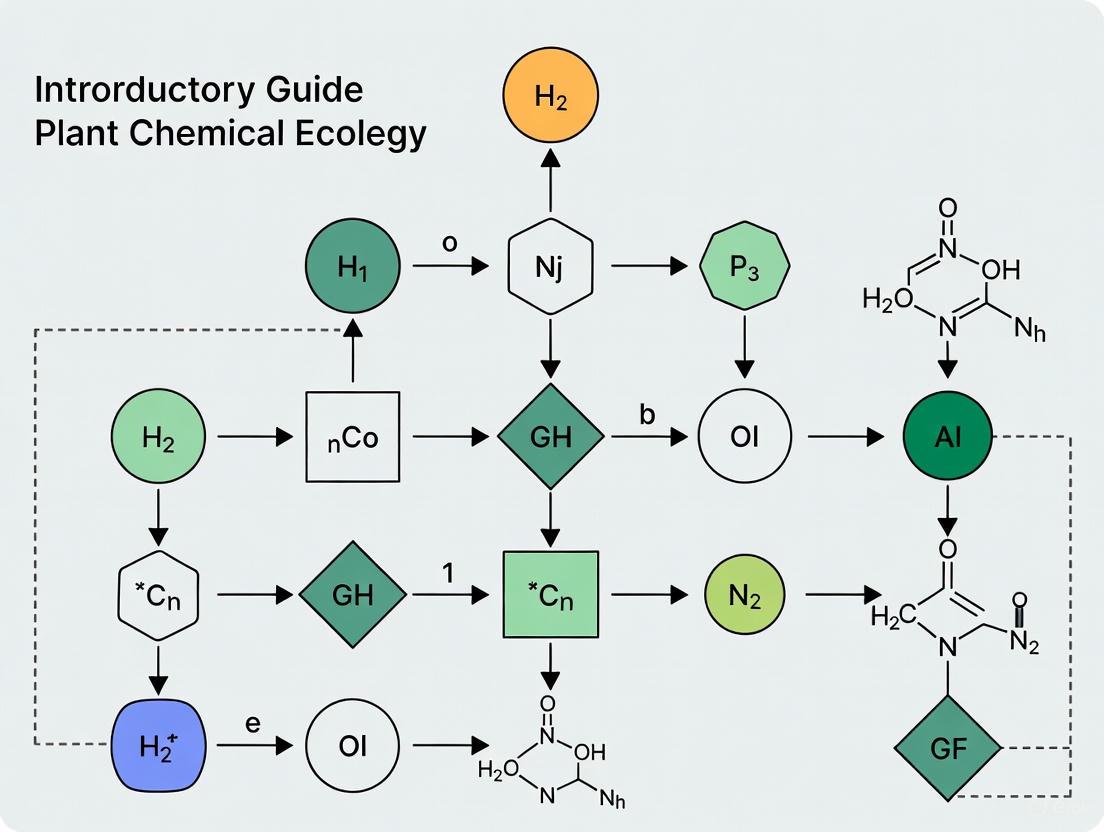

The following diagram illustrates the primary signaling pathways through which plants perceive stimuli and synthesize defensive compounds.

Plant Defense Signaling Pathway

The chemical agents that mediate these interactions belong to several major classes, whose functions are summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Key Chemical Classes in Plant Chemical Ecology

| Chemical Class | Primary Ecological Function(s) | Example Compounds |

|---|---|---|

| Terpenoids | Herbivore repellence, pollinator attraction, indirect defense via natural enemy recruitment [2]. | 1,8-cineole, β-myrcene, pulegone [2]. |

| Phenolics | Antioxidant activity, allelopathy, herbivore deterrence, structural support [1]. | Tellimagrandin II (hydrolyzable polyphenol), coumarins [1]. |

| Nitrogen-Containing Compounds | Potent toxicity and deterrence against herbivores and pathogens [1]. | Alkaloids, cyanogenic glycosides. |

| Fatty Acid Derivatives | Wound signaling, induction of defense gene expression, volatile signaling for indirect defense [1]. | Jasmonic acid, green leaf volatiles (GLVs). |

Standard Experimental Methodologies

Research in plant chemical ecology relies on robust, reproducible protocols to isolate, identify, and characterize chemical-mediated interactions.

Protocol 1: Behavioral Bioassays for Insect Response

This methodology tests the behavioral response of insects (e.g., attraction or repellence) to plant volatiles or specific compounds [2].

- Stimulus Preparation: Extract volatile compounds from plant material using steam distillation or solvent extraction. Alternatively, use synthetic standards of suspected bioactive compounds [2].

- Olfactometer Setup: Use a Y-tube or multi-arm olfactometer where an air stream passed over the test stimulus and a control (e.g., pure solvent) is presented in different arms [2].

- Insect Introduction: Individual insects are introduced at the base of the olfactometer and observed for a set period.

- Data Collection and Analysis: Record the insect's first choice and time spent in each odor zone. Analyze data using binomial tests or ANOVA to determine significant preferences [2].

Protocol 2: Collection and Analysis of Plant Volatiles

This protocol details the workflow for capturing and identifying volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emitted by plants [5].

Plant Volatile Analysis Workflow

- Headspace Sampling: Enclose a plant or plant part in an inert container (e.g., a glass chamber or plastic oven bag). Pull clean, humidified air through the chamber and over the plant material. Volatiles are trapped on adsorbent traps, such as those containing Super-Q or Tenax TA [5] [2].

- Chemical Elution: Volatiles are desorbed from the traps using a small volume of a high-purity solvent like hexane or dichloromethane.

- Chemical Analysis: The eluent is analyzed using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) or Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS). These instruments separate the complex mixture and provide data for compound identification [5] [3].

- Data Analysis: The resulting chromatograms are processed using software (e.g., Proteome Discoverer for proteomics or analogous platforms for metabolomics) to identify and quantify compounds by comparing mass spectra and retention times to databases and authentic standards [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimentation requires specific reagents and instruments. The following table lists key materials used in foundational plant chemical ecology experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| GC-MS (Gas Chromatograph-Mass Spectrometer) | The workhorse instrument for separating, identifying, and quantifying volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from plant headspace or extracts [3] [2]. |

| LC-MS (Liquid Chromatograph-Mass Spectrometer) | Used for analyzing non-volatile or thermally labile secondary metabolites, such as many phenolic compounds and alkaloids [3]. |

| Olfactometer (Y-tube or multi-arm) | Standard apparatus for conducting behavioral bioassays to test insect attraction or repellence to specific odors under controlled laboratory conditions [2]. |

| Electroantennography (EAG) | A technique that measures the electrical response of an insect antenna to volatile compounds, confirming the insect can physiologically detect the odor [2]. |

| Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) Reagents | Used in quantitative proteomics (e.g., apoplast proteome analysis) to label peptides from different samples, allowing for their multiplexed analysis and relative quantification in a single MS run [5]. |

| Adsorbent Traps (Super-Q, Tenax TA) | Porous polymer materials used to collect and concentrate volatile compounds from air samples during headspace collection [2]. |

| Murashige & Skoog (MS) Medium | A standardized, widely used plant growth medium that can be modified to create synthetic environments, such as artificial root exudate media, for studying microbial interactions [5]. |

Applications and Future Directions

The principles of plant chemical ecology are directly translated into sustainable agricultural applications. A major focus is the development of push-pull strategies, where pest insects are repelled from the crop (push) using repellent intercrops or synthetic stimuli and simultaneously attracted (pull) to trap plants on the periphery [1]. Research into volatile blends that efficiently attract natural enemies is also crucial for enhancing biological control within IPM frameworks [1] [3].

Future research is moving towards a more holistic and multidisciplinary approach, integrating insights from evolutionary ecology, molecular biology, and ethnopharmacology [6]. Key future directions include investigating volatile mosaics in natural, multi-species communities under multiple stressors, leveraging metabolic engineering, and understanding the complex effects of climate change on these finely tuned chemical interactions [1].

Plant secondary metabolites (SMs) represent a vast array of organic compounds that, while not directly involved in primary growth or development, are indispensable for plant survival and ecological interactions [7] [8]. These compounds are synthesized through specialized metabolic pathways derived from primary metabolism and are often produced in response to environmental cues or stress conditions [9] [10]. The three major classes of SMs—terpenoids, alkaloids, and phenolics—serve as key defensive agents against herbivores, pathogens, and abiotic stresses, while also mediating beneficial interactions such as pollinator attraction [9] [10]. Beyond their ecological roles, these compounds possess a remarkable breadth of biological activities, making them invaluable resources for pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and agricultural applications [8] [11] [12]. This review provides a comprehensive technical overview of the biosynthesis, ecological functions, and therapeutic potential of these core SM classes, framing them within the context of plant chemical ecology and modern drug discovery paradigms.

Major Classes of Plant Secondary Metabolites

Terpenoids

Terpenoids, also known as isoprenoids, constitute the largest and most structurally diverse family of SMs, with over 40,000 identified compounds [13] [14]. Their basic structural unit is the five-carbon isoprene (C5H8) molecule. Terpenoid biosynthesis proceeds via two independent pathways: the cytosolic mevalonic acid (MVA) pathway and the plastidial methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway, both of which produce the universal five-carbon precursors isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and its isomer dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) [15] [14].

Table 1: Classification and Examples of Major Terpenoids

| Class | Carbon Units | Representative Compounds | Major Biological Activities | Plant Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monoterpenes | C10 | Limonene, Linalool, Myrcene, 1,8-Cineole | Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, Aromatic | Citrus fruits, Mint, Lavender, Eucalyptus [7] [13] |

| Sesquiterpenes | C15 | β-Caryophyllene, Farnesene, Humulene | Anti-inflammatory, Antimicrobial, Phytotoxic | Cannabis, Black pepper, Ginger [7] |

| Diterpenes | C20 | Gossypol, Taxol, Phytol | Anticancer (Taxol), Antioxidant (Phytol) | Pacific yew (Taxus), Cotton [7] [12] |

| Triterpenes | C30 | Squalene, Digitoxin, Lupeol | Cardioactive (Digitoxin), Anticancer | Foxglove, Olive oil [7] [12] |

| Tetraterpenes | C40 | Carotenoids (β-carotene, Lutein) | Antioxidant, Photoprotective, Provitamin A | Carrots, Tomatoes, Saffron [7] [15] |

Terpenoids play multifaceted roles in plant defense and physiology. They function as direct antimicrobial and antifeedant compounds, with mechanisms including cell membrane disruption [13], inhibition of ATPase activity [13], and interference with quorum sensing in bacteria [13]. Monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes are major components of essential oils, contributing to plant aroma and mediating indirect defense by attracting natural enemies of herbivores [14]. Beyond defense, certain terpenoids serve as photosynthetic pigments (carotenoids), electron carriers (ubiquinone), membrane stabilizers (phytosterols), and plant hormones (gibberellins, abscisic acid) [7] [15].

Alkaloids

Alkaloids are a large group of nitrogen-containing compounds, typically derived from amino acid precursors, that exhibit pronounced pharmacological activities [7] [8]. Their basic skeletons are biosynthesized from various amino acids (e.g., tyrosine, tryptophan, lysine, ornithine), with post-modifications creating immense structural diversity [7]. These compounds are characterized by a heterocyclic ring containing nitrogen and are often alkaline in nature [7].

Table 2: Classification and Properties of Major Alkaloids

| Class/Biosynthetic Origin | Representative Compounds | Medicinal Properties | Plant Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benzylisoquinoline (Tyrosine) | Morphine, Codeine, Berberine | Analgesic (Morphine), Antitussive (Codeine), Antimicrobial (Berberine) | Opium poppy (Papaver somniferum), Goldenseal [7] [11] [12] |

| Tropane (Ornithine) | Cocaine, Atropine, Scopolamine | Local anesthetic (Cocaine), Mydriatic (Atropine), Anti-emetic (Scopolamine) | Coca plant, Deadly nightshade, Henbane [12] |

| Indole (Tryptophan) | Reserpine, Vinblastine, Quinine | Antihypertensive (Reserpine), Anticancer (Vinblastine), Antimalarial (Quinine) | Rauwolfia, Madagascar periwinkle, Cinchona bark [7] [12] |

| Purine (Xanthosine) | Caffeine, Theobromine | Stimulant, Bronchodilator | Coffee, Tea, Cacao [7] |

| Steroidal (with terpenoid pathway) | Solanine, Chaconine | Toxic glycoalkaloids with insecticidal and antifungal properties | Potato, Tomato (Solanaceae family) [10] |

Alkaloids function primarily as potent defense compounds in plants, with many exhibiting neurotoxic, cytotoxic, or hormonal effects on herbivores and pathogens [7] [10]. Their nitrogen-containing structures often allow them to interfere with neurotransmitter systems in animals, making them effective deterrents [7]. The pharmacological activities of alkaloids in humans frequently mirror their ecological functions, with many acting on neurological, cardiovascular, and cellular systems at precise therapeutic doses [7] [12].

Phenolic Compounds

Phenolic compounds are characterized by the presence of at least one aromatic ring bearing one or more hydroxyl groups. They constitute one of the most abundant classes of plant SMs, with over 8,000 identified structures [8]. Their biosynthesis primarily occurs through the shikimic acid and phenylpropanoid pathways, with phenylalanine serving as a key precursor [7] [16].

Table 3: Major Subclasses of Phenolic Compounds and Their Functions

| Subclass | Basic Structure | Representative Compounds | Biological Roles & Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Phenolics | C6-C1 | Gallic acid, p-Coumaric acid | Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, Anticancer [7] |

| Flavonoids | C6-C3-C6 | Quercetin, Rutin, Anthocyanins, Catechin | Antioxidant, Pigmentation (Anthocyanins), UV protection [7] [16] |

| Lignans & Lignins | (C6-C3)n | Pinoresinol, Secoisolariciresinol | Structural support (Lignin), Phytoestrogenic activity [8] |

| Stilbenes | C6-C2-C6 | Resveratrol, Pterostilbene | Antifungal (Phytoalexins), Cardioprotective, Anticancer [7] |

| Tannins | Polymerized phenolics | Condensed & Hydrolyzable tannins | Herbivore deterrent (protein binding), Antioxidant [7] [10] |

Phenolics play crucial roles in plant defense as antioxidants, antimicrobial phytoalexins, and herbivore deterrents (particularly tannins which reduce palatability by binding proteins) [10]. Their antioxidant activity stems from the ability to donate hydrogen atoms or electrons to free radicals, thereby neutralizing reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated under abiotic stresses like UV exposure, drought, and metal toxicity [15] [10]. In addition, flavonoids and anthocyanins contribute to plant pigmentation, attracting pollinators and seed dispersers, while lignin provides structural support to cell walls [7] [16].

Biosynthetic Pathways and Regulatory Networks

Pathway Diagrams and Cross-Talk

The biosynthesis of all three major SM classes is intricately linked to primary metabolic pathways. The following diagram illustrates the core biosynthetic routes and their interconnection:

Figure 1: Biosynthetic pathways of plant secondary metabolites showing cross-talk between primary and specialized metabolism. The MEP (methylerythritol phosphate) and MVA (mevalonate) pathways generate terpenoid precursors; the shikimate and phenylpropanoid pathways lead to phenolic compounds; and various amino acid precursors give rise to different alkaloid classes.

Regulation by Environmental Factors and Signaling Molecules

SM biosynthesis is dynamically regulated by environmental factors including light, temperature, herbivory, and pathogen attack [16] [15] [10]. Light quality and intensity significantly influence SM accumulation through photoreceptors (phytochromes, cryptochromes, UVR8) and downstream transcription factors like HY5 and PIFs [16]. For instance, UV-B perception by UVR8 stabilizes HY5, which directly activates promoters of key phenylpropanoid genes such as CHS (chalcone synthase) and DFR (dihydroflavonol reductase), enhancing flavonoid and anthocyanin production [16].

Biotic and abiotic stresses trigger complex signaling networks involving phytohormones and other signaling molecules that modulate SM pathways:

Figure 2: Signaling networks regulating secondary metabolite biosynthesis. Environmental stresses trigger phytohormonal and signaling cascades that activate transcription factors, leading to the upregulation of terpenoid, alkaloid, and phenolic pathways.

Jasmonic acid (JA) and salicylic acid (SA) serve as master regulators of induced defense responses [10]. JA signaling typically activates defense against herbivores and necrotrophic pathogens, enhancing the production of alkaloids, terpenoids, and phenolics [15] [10]. For example, methyl jasmonate (MeJA) elicitation upregulates WRKY transcription factors that activate artemisinin (sesquiterpene) biosynthesis in Artemisia annua and taxol (diterpene) biosynthesis in Taxus species [15]. SA, conversely, is primarily involved in defense against biotrophic pathogens and systemic acquired resistance, often stimulating phenolic and flavonoid accumulation [10].

Experimental Methodologies for SM Analysis

Protocol for Induced SM Production and Analysis

Objective: To elicit and quantify the production of secondary metabolites in plant tissue cultures in response to jasmonic acid elicitation.

Materials:

- Sterile plant tissue cultures (e.g., Catharanthus roseus for alkaloids, Artemisia annua for terpenoids)

- Methyl jasmonate (MeJA) stock solution (100 mM in ethanol)

- Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium with appropriate plant growth regulators

- Solvents: methanol, ethanol, chloroform (HPLC grade)

- Analytical standards (e.g., artemisinin, vincristine, rutin)

- LC-MS/MS system with reverse-phase C18 column

Procedure:

- Culture Establishment: Maintain plant cell suspension cultures in appropriate medium under standard growth conditions (25°C, 16/8h light/dark cycle, orbital shaking at 110 rpm).

- Elicitor Treatment: During the logarithmic growth phase (typically day 7-10), add MeJA to final concentrations of 50-200 µM. Include controls with equivalent solvent only.

- Harvesting: Collect cells by vacuum filtration at 24h, 48h, 72h, and 96h post-elicitation. Flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C.

- Metabolite Extraction:

- Homogenize 100 mg frozen tissue in 1 mL 80% methanol using a bead beater.

- Sonicate for 15 min at 4°C, then centrifuge at 13,000 × g for 10 min.

- Transfer supernatant, repeat extraction twice, pool supernatants.

- Concentrate under nitrogen gas and reconstitute in 100 µL methanol for analysis.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis:

- Employ reverse-phase chromatography with water-acetonitrile gradient.

- Use multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) for target metabolite quantification.

- Quantify against calibration curves of authentic standards.

- Gene Expression Analysis (Optional): Extract RNA, synthesize cDNA, and perform qRT-PCR for key biosynthetic genes (e.g., DBR2 for artemisinin, STR for alkaloids) to correlate metabolite accumulation with transcriptional regulation.

Expected Outcomes: MeJA treatment typically results in a 2-5 fold increase in target SMs within 48-72 hours, accompanied by upregulation of biosynthetic gene expression [15].

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Secondary Metabolite Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Uses |

|---|---|---|

| Methyl Jasmonate (MeJA) | Chemical elicitor that activates JA signaling pathway | Inducing production of terpenoids (artemisinin), alkaloids (vincristine), and phenolics [15] |

| Salicylic Acid (SA) | Chemical elicitor that activates SA signaling pathway | Enhancing phenolic compound and phytoalexin production in pathogen defense responses [10] |

| Yeast Extract | Complex biotic elicitor containing microbial patterns | Stimulating caffeoylquinic acid production in Arnica montana [9] |

| SILK (Shikimic Acid-Inositol-L-Kinetin) Medium | Specialized culture medium for enhanced phenolic production | Optimized culture system for stilbene production in Reynoutria japonica [9] |

| HPLC/DAD-ESI-MS | Analytical instrumentation for metabolite separation and identification | Quantifying and identifying terpenes, alkaloids, and phenolics in complex plant extracts [11] |

| Hairy Root Cultures | Transformed root cultures for stable metabolite production | Enhanced centelloside (triterpene) production in engineered Centella asiatica [9] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Genome editing tool for pathway engineering | Creating knockouts in regulatory genes to enhance SM production [10] |

Applications and Future Perspectives

Plant secondary metabolites have extensive applications across multiple industries. In pharmaceuticals, they serve as direct therapeutic agents (e.g., morphine, artemisinin, paclitaxel), lead compounds for synthetic optimization, and adjuvant therapies to enhance drug efficacy or counteract resistance [11] [12]. In agriculture, SMs are utilized as natural pesticides, herbicides, and plant growth regulators, offering eco-friendly alternatives to synthetic agrochemicals [8] [10].

Future research directions focus on overcoming production challenges through biotechnological approaches. Metabolic engineering in plant systems or microbial hosts (synthetic biology) aims to enhance the yield of valuable SMs [7] [11]. For instance, the complete biosynthetic pathway of the anticancer diterpene paclitaxel (Taxol) has been recently elucidated, paving the way for heterologous production [9] [12]. Advanced "omics" technologies (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) are being integrated to map regulatory networks and identify key genetic elements for engineering [11] [10]. Furthermore, understanding how environmental factors control SM biosynthesis will enable the development of precision cultivation practices to optimize metabolite yields in medicinal plants [16] [15].

In conclusion, terpenoids, alkaloids, and phenolics represent a spectacular chemical arsenal that plants have evolved to interact with their environment. Their structural diversity, biological activities, and ecological significance continue to inspire scientific inquiry and technological innovation across multiple disciplines. As research methodologies advance, our ability to harness the full potential of these remarkable compounds for human health and sustainable agriculture will undoubtedly expand.

Plant chemical ecology is the discipline that investigates how naturally occurring chemical signals mediate ecological interactions between organisms across trophic levels [17]. Because plants are sessile and cannot move away from unfavorable conditions, they have evolved a complex suite of chemical traits that allow them to negotiate interactions with other organisms, simultaneously attracting mutualists such as pollinators while repelling antagonists such as herbivores [18] [19]. These interaction-mediating traits have been well studied for plant interactions with herbivores as antagonists and pollinators as mutualists, to the extent that they have become models for understanding biotic interactions in general [18].

The fundamental challenge plants face is particularly apparent when considering chemical traits mediating biotic interactions: how do plants attract mutualists and repel antagonists with the same suite of basic traits, relying largely on secondary metabolites, and within the same information space? [18] [19] This conflict is most evident in the multifunctionality of secondary metabolites, which suggests diffuse reciprocal natural selection on plant secondary metabolism by both pollinator and herbivore communities associated with a plant [18]. This dynamic interaction between defense and reproduction has significant implications for plant fitness, evolutionary paths, and the development of sustainable agricultural practices [17].

Core Chemical Mediators in Ecological Interactions

Secondary Metabolites as Multifunctional Signals

Plant secondary metabolism enables plants to limit potential antagonistic interactions through constitutive defenses and to involve entire interaction communities in defense strategies through information transfer via induced responses [18] [19]. These chemical compounds function as nature's sophisticated language, facilitating communication within and between species:

- Constitutive defenses: Toxic, anti-digestive, and anti-nutritive compounds that directly protect against herbivores and pathogens [18]

- Induced defenses: Chemical responses activated following attack, including herbivory-induced production of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that attract predators and parasitoids of herbivores [18]

- Pollinator rewards: Nectar, pollen, and oils containing many of the same defensive compounds found in leaves, consequently exposing pollinators to the same chemical traits that deter herbivores [18]

The multifunctionality of these secondary metabolites creates an evolutionary tension where plants must balance the competing demands of defense and reproduction, as the same chemical traits that deter herbivores may also influence pollinator behavior [18].

Key Chemical Compound Classes and Their Functions

Table 1: Major classes of plant secondary metabolites and their ecological functions

| Compound Class | Primary Ecological Functions | Target Organisms | Examples in Plant Families |

|---|---|---|---|

| Terpenoids | Direct defense against herbivores, pollinator attraction via floral scents | Insects, mammals, pathogens | Volatile monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes in Lamiaceae |

| Phenolics | Antioxidant activity, structural defense, pigmentation for pollinator visual cues | Insects, competing plants, pollinators | Flavonoids in Asteraceae, tannins in Fagaceae |

| Alkaloids | Toxicity and deterrence through neuroactive and digestive-disrupting properties | Herbivorous insects, vertebrates | Pyridine alkaloids in Solanaceae |

| Glucosinolates | Defense activation upon tissue damage, specialist herbivore attraction | Generalist and specialist insects | Glucosinolates in Brassicaceae |

| Green Leaf Volatiles (GLVs) | Indirect defense via carnivore attraction, direct repellency | Herbivores, carnivorous insects | C6-aldehydes, alcohols in numerous plant families |

Experimental Approaches in Chemical Ecology

Methodological Framework for Studying Plant-Insect Interactions

Modern chemical ecology employs integrated approaches that combine traditional experimental methods with advanced technologies to unravel the complexity of plant-pollinator-herbivore interactions [18]. The research workflow typically follows a systematic process from field observation to molecular mechanism identification, with key methodological considerations for ensuring data reliability and reproducibility:

Objective vs. Subjective Data Collection: Research in chemical ecology requires careful distinction between objective data (fact-based, measurable, and observable) and subjective data (based on opinions, points of view, or emotional judgment) to ensure scientific rigor [20]. Quantitative measurements gather numerical data (e.g., VOC concentration in nanograms per hour), while qualitative measurements describe qualities (e.g., behavioral preference in choice assays) [20].

Data Presentation Standards: Effective presentation of chemical ecology data requires proper organization through data tables and graphs. Data tables should clearly label rows and columns, include units of measurement, and provide descriptive captions [20]. Line graphs are particularly useful for displaying changes in volatile emission or compound concentration over a continuous range, such as temporal patterns of metabolite production following herbivory [20].

Chemical ecology researchers have access to numerous specialized resources for experimental protocols and methodological guidance, including both licensed and open-access platforms that provide detailed technical procedures:

Table 2: Essential methodological resources for chemical ecology research

| Resource Name | Resource Type | Key Applications in Chemical Ecology | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methods in Ecology and Evolution [21] | Journal | Protocol development, field methods, methodological advances | Licensed |

| Current Protocols Series [21] | Protocol Database | Updated peer-reviewed protocols across biological disciplines | Licensed |

| Springer Nature Experiments [21] | Protocol Database | Over 60,000 protocols in molecular biology and biomedicine | Licensed |

| Cold Spring Harbor Protocols [21] | Protocol Database | Interactive source of new and classic research techniques | Licensed |

| JoVE (Journal of Visualized Experiments) [21] | Video Journal | Peer-reviewed methods articles with accompanying videos | Licensed |

| Methods in Enzymology [21] | Book Series | Detailed protocols for biochemical and biophysical techniques | Licensed |

| Bio-Protocol [21] | Protocol Database | Peer-reviewed protocols with interactive Q&A | Open Access |

| protocols.io [21] | Protocol Platform | Creating, organizing, and publishing reproducible protocols | Open Access |

Signaling Pathways in Plant-Insect Interactions

Jasmonate-Mediated Defense Signaling

The jasmonate pathway represents a central signaling mechanism that coordinates plant responses to herbivory and influences pollinator interactions through changes in floral traits and rewards [18]. Herbivory-induced jasmonate signaling can reverse the effects of tissue loss on male reproductive investment, demonstrating the interconnectedness of defense and reproduction [18].

Plant Defense Signaling Pathway: This diagram illustrates the jasmonate-mediated defense pathway that connects herbivore attack to both direct/indirect defenses and reproductive consequences.

Chemical Information Flow in Multitrophic Systems

Plants function as information hubs in ecological communities, processing and transmitting chemical signals that influence multiple trophic levels simultaneously. The flow of chemical information creates complex networks of interaction that extend from soil microorganisms to aerial predators, with plants serving as the central communication node [18] [17].

Multitrophic Chemical Communication: This diagram visualizes the plant as an information center mediating chemical communication across multiple trophic levels.

Case Studies in Integrated Ecological Functions

Pollinating Herbivores: The Ultimate Conflict

The challenges of attracting mutualists while repelling antagonists are particularly pronounced in systems involving pollinating herbivores, such as Lepidopteran species with herbivorous larvae and pollinating adults [18]. Research on Manduca sexta (tobacco hornworm) has demonstrated that defensive leaf volatiles play a crucial role in host plant selection, with adults assessing chemical information from leaves differently when choosing between foraging and oviposition locations [18]. This ontogenetic shift in chemical information use represents a sophisticated evolutionary adaptation that allows the same insect species to function as both pollinator and herbivore at different life stages.

Davidowitz et al. (2022) explored the resource allocation trade-offs in these systems, hypothesizing that increased allocation of resources to flight in Lepidopteran pollinators could lead to higher pollination efficiency and thus higher plant fitness [18]. Conversely, when the same insect increases resource allocation to reproduction instead of flight, herbivore population size is likely to increase with potentially negative consequences for plant fitness [18]. These resource allocation trade-offs between flight and fecundity in insects represent potential drivers of differential selection on plant defenses and counter-defenses in herbivore-pollinators [18].

Unexpected Pollinators: Ant-Mediated Pollination

While plant-visiting ants are typically functional herbivores or predators rather than pollinators, recent research has revealed unexpected exceptions to this pattern. Aranda-Rickert et al. (2021) provided the first evidence of distance-dependent contribution of ants to pollination in wind-pollinated Ephedra triandra, showing how ants can offset pollen limitation in isolated female plants by contributing to targeted delivery of airborne pollen while consuming sugary pollination drops [18]. This discovery challenges conventional categorization of ecological functions and demonstrates the context-dependent nature of species interactions.

Herbivore-Mediated Selection on Floral Traits

Pollinators and herbivores can exert conflicting selection pressures on plant reproductive and defensive traits, creating evolutionary dilemmas that shape floral phenotype expression. Wu et al. (2021) demonstrated that herbivore-mediated selection can generate selective pressures for greater flower production in insect-pollinated plants, indicating that variation in the intensity of plant-antagonistic interactions can drive spatial variation in natural selection on floral traits [18]. This finding highlights the importance of considering both mutualists and antagonists when studying the evolution of plant reproductive traits.

Applied Applications in Agriculture and Pest Management

Chemical Ecology in Integrated Pest Management

The principles of chemical ecology can be directly applied to develop sustainable pest management strategies that leverage naturally occurring chemical signals rather than relying exclusively on synthetic pesticides [17]. Chemical cues (semiochemicals) play key roles in integrated pest management programs by mediating interactions between plants, insects, and microorganisms [17]. These approaches include:

- Induced plant defenses: Application of chemical elicitors that prime or directly activate plant defense systems against pests [17]

- Direct pest suppression: Use of repellent or antifeedant compounds that directly deter pest establishment and feeding [17]

- Beneficial insect signaling: Deployment of attractant semiochemicals that recruit natural enemies of pests, facilitating biological control [17]

Recent advances in chemical ecology research have enhanced our understanding of how chemical interactions between plants, insects, and microorganisms can be harnessed for sustainable pest management in agricultural and horticultural crops [17]. The special issue published in Pest Management Science (2023-2025) showcases cutting-edge research that can advance the field in tackling global pest management challenges [17].

Experimental Reagents and Research Tools

Table 3: Essential research reagents and methodological solutions for chemical ecology studies

| Reagent/Method Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volatile Collection Systems | Dynamic headspace collection, Solid Phase Microextraction (SPME) | Capturing plant volatiles for identification and quantification | Sensitivity to low-concentration compounds, artifact prevention |

| Chemical Identification Tools | GC-MS, LC-MS, NMR, HPLC | Structural elucidation of semiochemicals and defense compounds | Reference library availability, resolution requirements |

| Behavioral Assay Equipment | Olfactometers, wind tunnels, flight cages, choice test arenas | Measuring insect responses to chemical cues | Environmental control, appropriate replication |

| Molecular Biology Tools | RNAi, CRISPR-Cas9, qPCR, RNA-Seq | Manipulating and measuring gene expression in chemical ecology | Species-specific protocol adaptation |

| Chemical Synthesis Methods | Asymmetric synthesis, enantioselective preparation | Producing stereochemically pure semiochemicals | Chirality effects on biological activity |

| Field Application Systems | Slow-release dispensers, aerosol emitters, trap designs | Deploying semiochemicals in ecological settings | Release rate optimization, environmental stability |

Future Directions and Research Priorities

Despite significant advances in understanding plant-pollinator-herbivore interactions, the evolutionary consequences of these complex ecological interactions remain incompletely understood [18] [19]. Future research priorities should focus on integrating traditional experimental approaches with modern methodologies including next-generation sequencing, metabolomics, and gene-editing technologies to enhance our understanding of the genes and traits involved in mediating complex ecological interactions [18]. The emerging field of chemical ecology continues to develop new approaches for studying how naturally occurring chemical signals mediate ecological interactions across trophic levels [17].

Recent special issues and research topics have aimed to feature impactful developments in the field to identify paths forward, inspiring new ideas for future research and highlighting opportunities for collaborative approaches [18] [17]. As the discipline progresses, it will be increasingly important to unite the traditionally separate research fields of plant-pollinator and plant-herbivore interactions to develop a comprehensive understanding of how plants manage their ecological relationships through chemical signaling [18] [19]. This integrated approach will be essential for addressing global challenges in agriculture, conservation, and ecosystem management in the face of environmental change.

Plant chemical diversity, encompassing hundreds of thousands of specialized metabolites, represents a cornerstone of ecological interactions and adaptive evolution [22]. These compounds, traditionally studied for their roles in defense against herbivores and attraction of pollinators, demonstrate complex patterns across plant lineages, environments, and tissues. Understanding the drivers of this diversity requires integrating multiple biological disciplines, from evolutionary ecology to molecular biology. This technical guide synthesizes current knowledge on the relative contributions and interactions of three primary factors shaping plant chemodiversity: phylogenetic history, environmental selection, and tissue-specific functional demands. By examining the mechanistic bases and experimental approaches for investigating each driver, this review provides a comprehensive framework for researchers exploring the genesis and maintenance of chemical diversity in plants, with implications for drug discovery, sustainable agriculture, and biodiversity conservation.

Phylogenetic Constraints on Chemical Diversity

Evolutionary History as a Foundation

Phylogenetic relatedness imposes fundamental constraints on plant chemical diversity through conserved biosynthetic pathways and genetic architectures. Closely related species often share chemical characteristics due to common ancestry, creating phylogenetic patterns in metabolite production across plant lineages [22]. Nearly all members of Fabaceae, Solanaceae, and Lamiaceae, for instance, share particular chemical traits within their respective families [22]. This phylogenetic conservation occurs because evolutionary trajectories are channeled by existing enzymatic machinery and genetic regulatory networks, making some chemical innovations more probable than others.

The strength of phylogenetic influence varies significantly across plant groups and compound classes. In a study of eight wild fig species (Ficus spp.) from Madagascar, researchers detected a significant but moderate phylogenetic correlation in fruit and leaf chemodiversity [22]. Similarly, research on epiphytic macrolichens revealed a robust association between large-scale phylogeny and chemical niche adaptation, with calcium scores effectively distinguishing members of the Peltigerales from those of the Lecanorales [23]. This deep phylogenetic connection to chemical environment suggests ancient adaptation to specialized chemical regimes, with minor variation within families and genera likely stemming from more recent evolutionary processes [23].

Experimental Approaches for Detecting Phylogenetic Signals

Investigating phylogenetic influences on chemodiversity requires integrating comparative metabolomics with robust phylogenetic reconstruction. The experimental protocol typically involves several key stages, as demonstrated in the Malagasy fig study [22]:

Sample Collection: Researchers collected leaves and unripe fruits from eight sympatric Ficus species in a tropical rainforest, controlling for environmental variation by sampling within a single community.

Metabolomic Profiling: They applied untargeted metabolomics using ultra-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry to characterize chemical profiles of different organs.

Phylogenetic Reconstruction: The team reconstructed species relationships using six genetic markers, creating a phylogenetic framework for comparative analysis.

Statistical Integration: They employed phylogenetic comparative methods to quantify the degree to which chemical similarity corresponded to phylogenetic relatedness.

This integrated approach revealed that phylogenetic relatedness explained some variation in both fruit and leaf metabolomes, though functional convergence across species was also a major evolutionary driver [22].

Table 1: Key Studies Demonstrating Phylogenetic Signals in Plant Chemodiversity

| Plant System | Phylogenetic Scale | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malagasy Ficus species | Within genus | Moderate phylogenetic correlation in fruit and leaf chemodiversity | [22] |

| Epiphytic macrolichens | Across orders (Lecanorales vs. Peltigerales) | Strong phylogenetic association with calcium scores and chemical niches | [23] |

| Desert plants in Hexi Corridor | Across community | Phylogenetic diversity patterns differ from species diversity patterns | [24] |

| Zingiber species | Within genus | Phylogeny influences chemodiversity patterns | [22] |

| Protium (Burseraceae) | Within genus | Root compounds show phylogenetic structure while leaf compounds do not | [22] |

Environmental Drivers of Chemical Variation

Abiotic and Biotic Factors

Environmental factors exert profound selective pressures on plant chemical diversity through multiple mechanisms. Soil composition, precipitation patterns, temperature regimes, and biotic interactions collectively shape chemical profiles by favoring metabolites that enhance fitness under local conditions [24]. In desert plant communities of the Hexi Corridor, spatial patterns of chemical diversity were primarily regulated by soil available phosphorus, while phylogenetic structure was mainly influenced by annual mean temperature [24]. This demonstrates that different aspects of chemical diversity may respond to distinct environmental drivers.

Plant domestication has provided compelling evidence of environmental impacts on chemical profiles, often with unintended consequences. As plants were selectively bred for yield, flavor, or growth rate, many chemical defenses were reduced, lost, or modified [25]. Studies comparing wild and cultivated squash revealed that domesticated varieties lacked cucurbitacins but showed enhanced inducible trichome responses to herbivory, suggesting a shift from constitutive to inducible defense strategies under cultivation [25]. Similarly, wild cranberry genotypes exhibited higher levels of total phenolics and greater resistance to herbivores compared to modern cultivars, highlighting potential trade-offs between domestication goals and chemical defenses [25].

Experimental Assessment of Environmental Effects

Research on environmental drivers employs several methodological approaches to disentangle complex factor interactions:

Transplant Experiments: Standardized transplants of the lichen Lobaria pulmonaria were deployed across 90 canopies of Picea glauca x engelmannii across varying forest settings. After one year of exposure to different throughfall chemistries, elemental concentrations in the transplants quantified environmental influences on chemical composition [23].

Environmental Gradient Studies: Surveys of desert plant communities along the southeast to northwest transect in the Hexi Corridor documented changes in chemical diversity along longitudinal, latitudinal, and altitudinal gradients. Researchers measured geographical, climatic, and soil variables to identify their relative contributions to diversity patterns [24].

Common Garden Experiments: Growing genetically similar plants under controlled environmental conditions helps isolate specific factor effects. Such approaches have demonstrated that soil nutrients, particularly nitrogen and phosphorus availability, significantly influence the production of defensive compounds [24].

Table 2: Environmental Factors Driving Chemical Diversity in Plant Systems

| Environmental Factor | Impact on Chemical Diversity | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Soil Nutrients | Regulates investment in defense compounds; soil available phosphorus dominant driver in desert communities | [24] |

| Climate Variables | Temperature and precipitation patterns shape biogeographic patterns in chemical traits | [24] |

| Herbivore Pressure | Induces defense compounds; domestication reduces constitutive defenses | [25] |

| Throughfall Chemistry | Influences elemental composition and metabolic processes in epiphytic communities | [23] |

| Pathogen Exposure | Modifies chemical communication between plants and insect vectors | [26] |

Tissue-Specific Chemical Expression

Functional Specialization Across Organs

Tissue-specific metabolic expression represents a fundamental driver of chemical diversity, with different plant organs employing distinct chemical profiles tailored to their specific functions and vulnerability to antagonists [22]. Research on Malagasy fig species demonstrated that fruit and leaf metabolomes were more similar to the same organ in other species than to different organs within the same species [22]. This striking pattern indicates strong functional convergence driven by tissue-specific selective pressures, potentially overriding phylogenetic constraints.

The functional demands on different tissues vary substantially: leaves primarily face herbivore pressure and require defense compounds, while fruits must attract dispersers while protecting developing seeds, and roots engage in complex chemical dialogues with soil microbes [22] [27]. In Protium species, roots contained more volatile compounds but less structural diversity than leaves, and unlike leaf compounds which showed no phylogenetic correlation, root compounds in closely related species showed significant structural similarity [22]. This suggests that different evolutionary rules may govern chemical diversity in different tissue types, with root chemistry potentially under stronger phylogenetic constraint than leaf chemistry in this system.

Methodologies for Tissue-Specific Metabolomics

Investigating tissue-specific chemical diversity requires careful experimental design and analytical approaches:

Organ-Specific Sampling: Researchers must systematically collect and process different tissues from the same individuals, as demonstrated in the fig study where leaves and unripe fruits were separately analyzed from each tree [22].

Metabolomic Profiling: Untargeted approaches using UPLC-MS enable comprehensive characterization of tissue-specific metabolic networks without pre-selection for specific compound classes [22].

Spatial Localization Techniques: Methods like mass spectrometry imaging help visualize the distribution of specific compounds within and between tissues, revealing micro-scale patterns in chemical allocation.

Comparative Analysis: Statistical comparisons of metabolic profiles across tissues and species identify compounds that are tissue-specific versus those that are conserved across organs.

Integrated Framework and Experimental Applications

Interplay of Multiple Drivers

Plant chemical diversity emerges from the complex interplay of phylogenetic history, environmental factors, and tissue-specific requirements rather than any single driver [22] [27] [24]. The relative importance of each factor varies across plant systems, compounds, and ecological contexts. In the Malagasy fig system, both phylogenetic constraints and tissue-specific functional convergence significantly shaped chemical diversity, with organ type being a stronger predictor of chemical profile than species identity for certain compounds [22].

Emerging research suggests that specialized metabolites may have evolved under dual selection pressures—external ecological functions and intrinsic cellular roles [27]. Many specialized metabolites and their precursors act as cellular signals regulating growth and differentiation, suggesting these internal functions may be equally important as ecological interactions in shaping chemical evolution [27]. This expanded framework necessitates research approaches that simultaneously address multiple drivers rather than focusing on single factors.

Integrated Experimental Workflow

A comprehensive approach to investigating chemical diversity drivers incorporates multiple methodologies in a unified framework:

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Chemical Ecology Studies

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Instrumentation | UPLC-MS, GC-MS, LC-MS | Untargeted and targeted metabolomic profiling of plant tissues |

| Genetic Markers | Six genetic markers used in fig phylogeny | Phylogenetic reconstruction and evolutionary analysis |

| Chemical Standards | Cucurbitacins, terpenoids, phenolics | Compound identification and quantification |

| Field Collection Materials | Silica gel, standardized transplant materials | Sample preservation and experimental standardization |

| Bioinformatics Tools | RAxML, cophenetic function in R | Phylogenetic tree construction and statistical analysis |

| Environmental Sensors | Soil nutrient kits, throughfall collectors | Quantification of environmental variables |

Plant chemical diversity is orchestrated by the complex interplay of phylogenetic history, environmental selection, and tissue-specific functional demands. Understanding these drivers requires integrated approaches that combine metabolomic profiling, phylogenetic comparative methods, and environmental analysis. Future research leveraging single-cell multi-omics and evolutionary genomics will provide unprecedented resolution on the evolutionary processes behind chemical diversification [27]. This comprehensive understanding of chemical diversity drivers has significant implications for drug discovery by identifying novel bioactive compounds, sustainable agriculture through optimized plant defenses, and biodiversity conservation by elucidating the mechanisms maintaining ecological interactions.

Plant chemical ecology examines the evolutionary origins and ecological functions of specialized (secondary) metabolites, which serve as a cornerstone for drug discovery. These compounds, including morphine and artemisinin, are not merely products of random biochemical events but have evolved as sophisticated adaptations to environmental pressures. This whitepaper explores the journey from traditional plant remedies to modern pharmaceutical applications, using artemisinin as a central case study to illustrate the convergence of ecology, traditional knowledge, and cutting-edge biotechnology in addressing global health challenges. The discovery and development of artemisinin, a potent antimalarial sesquiterpene lactone from Artemisia annua, exemplifies how understanding plant chemical ecology can lead to transformative medicines and sustainable production solutions.

Historical Context: From Plant Remedies to Pure Compounds

For centuries, human societies have relied on plant-based medicines, with knowledge often codified in traditional healing systems. The isolation of morphine from opium poppy in the early 19th century marked a pivotal transition from crude plant preparations to purified single-entity drugs, establishing a paradigm for pharmaceutical development. This approach yielded numerous life-saving medicines but often failed to capture the ecological context and synergistic relationships inherent in traditional use.

The discovery of artemisinin in 1972 from the medicinal plant Artemisia annua L. (sweet wormwood or 'qinghao') by Professor Youyou Tu and her team revived interest in systematically investigating traditional pharmacopeias [28] [29]. The research was initiated under China's Project 523 in response to the urgent need for new antimalarial drugs as resistance to chloroquine spread globally [29]. The success of artemisinin, which earned the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2015, demonstrated that ancient remedies could yield modern therapeutic breakthroughs when investigated through rigorous scientific methodology.

Artemisinin: A Masterpiece of Plant Chemical Ecology

Ecological Function and Biosynthesis

Artemisinin production in A. annua represents a sophisticated chemical defense strategy shaped by evolutionary pressures. This sesquiterpene lactone with an endoperoxide bridge is uniquely synthesized in the glandular secretory trichomes (GSTs) of leaves and floral tissues [30] [29]. The biosynthetic pathway exemplifies the compartmentalization and regulatory complexity of plant specialized metabolism.

The pathway begins with the condensation of isoprenoid precursors from both the cytosolic mevalonate (MVA) pathway and the plastidial methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway [31] [29]. Farnesyl diphosphate synthase (FPPS) catalyzes the formation of 15-carbon farnesyl diphosphate (FPP), which enters the dedicated artemisinin pathway. Amorpha-4,11-diene synthase (ADS) cyclizes FPP to form amorpha-4,11-diene, the first committed precursor [31]. A cytochrome P450 monooxygenase (CYP71AV1) with its reductase (CPR) then oxidizes amorpha-4,11-diene to artemisinic alcohol, artemisinic aldehyde, and artemisinic acid [31] [29]. A branch point occurs at artemisinic aldehyde, where artemisinic aldehyde Δ11(13) reductase (DBR2) produces dihydroartemisinic aldehyde, which is subsequently oxidized to dihydroartemisinic acid (DHAA) by aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1) [31]. The final conversion to artemisinin occurs non-enzymatically through photo-oxidation in the subcuticular space of GSTs [31] [30].

Figure 1: Artemisinin Biosynthesis Pathway in Artemisia annua. The pathway shows key enzymatic steps from farnesyl diphosphate (FPP) to artemisinin, highlighting the branch point at artemisinic aldehyde [31] [29].

Artemisinin serves multiple protective functions within the plant, including defense against herbivores, pathogens, and abiotic stresses [30]. The compound can be phytotoxic due to reactive oxygen species generated during its degradation, but A. annua employs indigenous antioxidants like flavonoids and coumarins to mitigate this toxicity [30]. This ecological balancing act illustrates the sophisticated co-evolution of offensive and defensive chemistries in plants.

Mechanism of Action: Activation by Heme

Artemisinin's unique mechanism of action stems from its endoperoxide bridge, which is essential for antimalarial activity [28]. The drug is selectively toxic to malaria parasites due to their high heme concentration, a byproduct of hemoglobin digestion. Heme iron mediates the decomposition of the endoperoxide bridge, generating carbon-centered free radicals that alkylate heme and specific parasite proteins, including the translationally controlled tumor protein (TCTP) [28]. This alkylation disrupts parasite redox homeostasis and vital cellular processes, leading to parasite death. The heme-activated mechanism provides selective toxicity against Plasmodium parasites while minimizing harm to human hosts.

Modern Production Strategies: Bridging Supply Challenges

The low artemisinin content in A. annua (0.1-1% dry weight) combined with global demand for artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) has driven innovation in production methodologies [31] [32]. Traditional extraction alone cannot meet market needs, spurring development of complementary approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of Artemisinin Production Methods

| Method | Key Features | Yield/Productivity | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant Extraction | Field cultivation, solvent extraction | 0.1-1.0% dry weight [31] | Established method, utilizes natural photosynthesis | Land and water intensive, seasonal, content variability |

| Semi-synthesis | Microbial production of precursors (e.g., artemisinic acid) followed by chemical conversion | Artemisinic acid reached 25 g/L in engineered yeast [31] | Scalable fermentation, independent of agricultural constraints | Multi-step process, requires chemical conversion |

| Heterologous Biosynthesis | Reconstruction of pathway in microorganisms (E. coli, S. cerevisiae) | Amorphadiene: 24 mg/L in E. coli (initial) [31] | Sustainable, controllable production platform | Challenges with cytochrome P450 expression in prokaryotes [33] |

| Metabolic Engineering in Plants | Overexpression of pathway genes, blocking competitive pathways | Varies with transformation; significant increases reported [31] | Utilizes plant's native enzymatic environment | Requires transformation, regulatory approval |

Metabolic Engineering in Microorganisms

Seminal work by Keasling's laboratory demonstrated the feasibility of transferring artemisinin production from plants to microbial hosts. Initial efforts in E. coli produced 24 mg/L of amorpha-4,11-diene by expressing codon-optimized ADS and enhancing precursor supply [31]. However, functional expression of the plant cytochrome P450 (CYP71AV1) proved challenging in prokaryotic systems, necessitating a switch to S. cerevisiae [33]. Through decade-long optimization including fermentation process improvement, artemisinic acid titers reached 25 g/L, enabling development of a semi-synthetic production route [31]. This landmark achievement demonstrated the potential of synthetic biology for sustainable drug supply.

Plant Metabolic Engineering and Cultivation Optimization

Complementary to microbial production, efforts to enhance artemisinin content in A. annua have employed multiple strategies:

- Overexpression of pathway genes: Constitutive expression of ADS, CYP71AV1, CPR, DBR2, and ALDH1 to push flux toward artemisinin [31] [32]

- Transcription factor engineering: Modulation of AaWRKY1, AaERF1/2, AaORA, and other regulators to enhance pathway gene expression [32] [34]

- Blocking competitive pathways: Downregulation of genes diverting precursors to competing terpenoids [31]

- Elicitor strategies: Application of signaling molecules like jasmonic acid, silver nitrate, or salicylic acid to induce defense responses and artemisinin production [34]

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Artemisinin Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Pathway Enzymes | ADS, CYP71AV1, CPR, DBR2, ALDH1 | Reconstruction of biosynthetic pathway in heterologous hosts [31] [29] |

| Microbial Chassis | Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Escherichia coli | Platform for heterologous production; yeast preferred for P450 expression [31] [33] |

| Plant Growth Regulators | BAP, NAA, 2,4-D, AgNO₃ | Elicitation of artemisinin biosynthesis in callus and cell cultures [34] |

| Analytical Standards | Artemisinin, artemisinic acid, dihydroartemisinic acid | Quantification of artemisinin and precursors in biological samples [31] |

| Vector Systems | CRISPR/Cas9 constructs, overexpression vectors | Metabolic engineering in plants and microbes [32] |

Experimental Protocols

Heterologous Production inS. cerevisiae

Objective: Engineer yeast for high-titer production of artemisinic acid [31] [33]

Methodology:

- Host strain engineering: Modify endogenous mevalonate pathway to enhance flux to farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP)

- Pathway gene integration: Introduce codon-optimized plant genes (ADS, CYP71AV1, CPR, ADH1, ALDH1) under strong promoters

- Fermentation optimization: Employ controlled bioreactors with carbon source feeding, oxygen control, and product extraction

- Analytical quantification: Use HPLC-MS/MS to quantify artemisinic acid and intermediates

Key Considerations: Proper subcellular localization of cytochrome P450 enzymes to endoplasmic reticulum is critical for functionality [33]

Objective: Enhance artemisinin production through controlled stress application [34]

Methodology:

- Callus initiation: Establish callus cultures from sterile leaf explants on MS medium with plant growth regulators (e.g., 5 mg/L BAP + 1 mg/L NAA)

- Elicitor treatment: Supplement medium with 1 mg/L AgNO₃ as ethylene inhibitor and oxidative stress inducer

- Oxidative stress monitoring: Measure ascorbate peroxidase (APX) activity as biomarker of oxidative stress

- Metabolite analysis: Extract and quantify artemisinin, DHAA, and related metabolites after 2-4 weeks

Key Considerations: Elicitor effects are context-dependent; optimal concentrations must balance growth and secondary metabolism [34]

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Elicitation Studies in A. annua Callus Cultures. The diagram outlines key steps from explant establishment to metabolite analysis [34].

Expanding Therapeutic Applications and Future Directions

While best known for antimalarial activity, artemisinin and its derivatives show promise for diverse therapeutic applications. Clinical studies have investigated their use in cancer, viral infections (including COVID-19), inflammatory diseases, and dermatological conditions [35] [36]. Most studies report favorable safety profiles, with adverse events being rare and generally mild [36]. The broad bioactivity of artemisinin derivatives stems from their mechanism of free radical generation when activated by iron or other reducing agents, which can be exploited in pathological contexts with elevated iron concentrations (e.g., cancer cells).

Future research directions include:

- Novel delivery systems: Development of nanoparticle and liposomal formulations to enhance bioavailability and targeted delivery [35]

- Combinatorial approaches: Integration of multiple engineering strategies (CRISPR/Cas9, miRNA regulation, transcription factor modulation) for synergistic yield enhancement [32]

- Mechanism expansion: Exploration of artemisinin's effects on additional molecular targets and signaling pathways

- Sustainable production: Optimization of integrated systems combining plant breeding, metabolic engineering, and green chemistry

The journey of artemisinin from traditional remedy to modern pharmaceutical illustrates the profound potential of plant chemical ecology to address global health challenges. Its story embodies the convergence of traditional knowledge, ecological understanding, and technological innovation—from elucidating biosynthetic pathways and ecological functions to developing sustainable production platforms. As resistance to current artemisinin-based therapies emerges and new applications are discovered, the continued integration of advanced technologies with ecological principles will be essential. The field stands to benefit from viewing plant specialized metabolites not merely as chemical end products but as components of complex adaptive systems, offering insights for both drug discovery and sustainable manufacturing in an increasingly challenging global environment.

From Field to Lab: Analytical Techniques and Translational Applications

Plant chemical ecology is fundamentally the study of chemical interactions between plants and their environment. These interactions are directly mediated by the plant's metabolome, the complete set of small-molecule metabolites. Ecometabolomics has emerged as a powerful transdisciplinary field that applies metabolomic techniques to unravel the molecular mechanisms governing species interactions with their abiotic and biotic environment across different spatial and temporal scales [37]. Metabolomics provides several advantages for ecological research: it can be applied to any species without prior knowledge of its biochemical or genetic composition (crucial for studying non-model organisms), and it can reveal hundreds to thousands of metabolites from a single tissue, organ, or whole organism sample [37] [38].

The complexity of plant metabolomes is staggering, with estimates suggesting the plant kingdom produces between 200,000 to 1,000,000 metabolites [37]. This diversity includes both primary metabolites essential for growth and development, and specialized (secondary) metabolites that mediate ecological interactions such as defense against herbivores, attraction of pollinators, and response to environmental stresses [39]. Advanced analytical tools including GC-MS (Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry) and LC-MS (Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry) have become indispensable for detecting and quantifying these chemical mediators, enabling researchers to decode the chemical language of plants in their ecological contexts [37] [38] [39].

Core Analytical Technologies: Principles and Comparisons

Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS)

GC-MS has been a cornerstone of metabolomics for nearly 50 years and is often considered the "gold standard" due to its high standardization and reproducibility [40]. The technique is ideal for identifying and quantitating small molecular metabolites (<650 daltons) including organic acids, alcohols, sugars, amino acids, and fatty acids [40]. A critical requirement for GC-MS analysis is that compounds must be volatile enough for gas chromatography, which is typically achieved through chemical derivatization to replace active hydrogens (from -OH, -COOH, -NH2, or -SH groups) with non-polar trimethylsilyl groups [40].

Key advantages of GC-MS include:

- High chromatographic resolution and highly reproducible retention times [38]

- Powerful fragmentation through electron ionization (EI) which produces rich, reproducible mass spectra [40]

- Extensive spectral libraries (e.g., NIST, Wiley, Golm) containing spectra for over 200,000 compounds with standardized retention data [40]

- Automated data deconvolution capabilities using software like AMDIS to resolve co-eluting compounds [40]

The technology has evolved from classic single quadrupole detectors to include triple quadrupole systems for targeted quantification and accurate mass instruments (quadrupole-time of flight) for untargeted profiling [40].

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS)

LC-MS has become the most comprehensive platform for untargeted metabolomics due to its ability to analyze a wide range of metabolites without derivatization [38] [39]. The technique separates compounds in the liquid phase using various chromatographic columns (typically reverse-phase) and is most commonly coupled with electrospray ionization (ESI) [38]. LC-MS is particularly powerful for analyzing secondary metabolites such as flavonoids, alkaloids, and phenylpropanoids that are challenging for GC-MS [39].

Key advantages of LC-MS include:

- Broad metabolite coverage without need for derivatization [39]

- High sensitivity and selectivity for diverse compound classes [38]

- Compatibility with high-throughput analysis [38]

- Accurate mass capabilities using high-resolution mass spectrometers (Q-TOF, Orbitrap) for putative compound identification [38]

However, LC-MS faces challenges with retention time shifts in complex matrices and has smaller spectral libraries compared to GC-MS [38] [40].

Comparative Analysis of GC-MS and LC-MS Platforms

Table 1: Technical comparison of GC-MS and LC-MS for plant metabolomics

| Parameter | GC-MS | LC-MS |

|---|---|---|

| Ideal metabolite classes | Primary metabolites (sugars, organic acids, amino acids), volatiles | Secondary metabolites (flavonoids, alkaloids, phenylpropanoids), lipids [39] |

| Sample preparation | Requires derivatization (silylation) | Minimal preparation; direct injection possible [40] [39] |

| Separation basis | Volatility and polarity | Polarity (reverse-phase), hydrophobicity [38] |

| Ionization method | Electron Ionization (EI) | Electrospray Ionization (ESI) [38] [40] |

| Mass spectral libraries | Extensive (NIST: 242,477 compounds) | Limited (NIST: ~8,000 compounds) [40] |

| Quantitation | Excellent for targeted analysis | Good for both targeted and untargeted [40] |

| Data deconvolution | Mature algorithms (AMDIS, ChromaTOF) | Emerging approaches (SWATH) [40] |

Experimental Design and Workflow for Plant Ecometabolomics

Implementing metabolomics in ecological research requires careful experimental design and a multi-step workflow that integrates ecology, analytical chemistry, and bioinformatics [37]. A critical principle is "begin with the end in mind" – considering the final data analysis and biological questions during initial experimental design [37]. Proper replication is essential, with recommendations for 6-10 biological replicates per group for robust statistical power [37].

The complete workflow involves: (1) experimental design considering ecological context, (2) sample collection with careful timing and rapid stabilization, (3) metabolite extraction, (4) instrumental analysis, (5) data processing, and (6) statistical analysis and biological interpretation [37]. For field ecology studies, special challenges include obtaining sufficient replicates, providing proper storage conditions, and meeting export regulations (Nagoya protocols, phytosanitary regulations) [37].

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Sample Collection and Metabolite Extraction

Proper sample collection is critical for capturing accurate metabolic snapshots. For plant ecological studies, samples should be collected considering diurnal metabolic variations and rapidly stabilized using liquid nitrogen to halt enzymatic activity [37]. For comprehensive metabolite coverage, a ternary solvent extraction system (water, isopropanol, acetonitrile) effectively extracts metabolites across polarity ranges while minimizing interference from lipids that can cause matrix effects in GC-MS analysis [40].

A standardized extraction protocol for plant tissues includes:

- Rapid freezing of fresh tissue in liquid nitrogen

- Freeze-drying to preserve labile metabolites

- Homogenization using a mixer mill at cryogenic temperatures

- Extraction with cold ternary solvent mixture (water:isopropanol:acetonitrile)

- Lipid clean-up step to remove non-volatile lipids that can cause matrix effects in GC-MS

- Concentration under nitrogen stream or vacuum centrifugation [40]

For GC-MS analysis, the extracted metabolites require derivatization using methoxyamination (to protect carbonyl groups) followed by trimethylsilylation (to increase volatility) [40]. For LC-MS analysis, samples are typically reconstituted in mobile phase compatible solvents [39].

Instrumental Analysis Parameters

Table 2: Typical instrument parameters for GC-MS and LC-MS in plant metabolomics

| Parameter | GC-MS Settings | LC-MS Settings |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatography | DB-5MS column (30m × 0.25mm, 0.25μm); He carrier gas | C18 column (100 × 2.1mm, 1.8μm); water/acetonitrile + 0.1% formic acid [40] [39] |

| Temperature program | 60°C (1min) to 330°C at 10°C/min | 5-95% organic modifier over 15-30min [40] |

| Ionization | Electron Ionization (70eV) | Electrospray Ionization (positive/negative mode) [38] [40] |

| Mass analyzer | Quadrupole, QTOF | QTOF, Orbitrap [38] |

| Mass range | m/z 50-600 | m/z 50-1500 [40] |

| Scan rate | 2-20 Hz | 1-10 Hz [40] |

| Quality control | Pooled quality control samples, internal standards | Pooled QC samples, internal standards [40] |

Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

Data processing represents a significant challenge in ecometabolomics, requiring integration of ecological knowledge with biochemical and technical expertise [37]. The workflow includes multiple steps: peak detection, alignment, normalization, metabolite annotation, and statistical analysis [39].

For GC-MS data, automated mass spectral deconvolution using AMDIS or ChromaTOF separates co-eluting compounds, followed by spectral matching against libraries (NIST, Fiehnlib) with retention index matching for confident identification [40]. For LC-MS data, software packages like XCMS, MZmine, or MS-DIAL perform peak picking, alignment, and integration, though challenges remain with false-positive signals that require additional filtering strategies [39].

Statistical analysis must address the high-dimensional nature of metabolomics data (many variables, few samples) and high collinearity between metabolites [37]. Multivariate methods including Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) are commonly used, complemented by univariate statistics with appropriate multiple testing corrections [37].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key research reagents and materials for plant metabolomics

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Nitrogen | Rapid metabolic quenching | Preserves in vivo metabolic state during sampling [37] |

| Methanol, Acetonitrile, Isopropanol | Metabolite extraction | Ternary solvent system provides broad metabolite coverage [40] |

| Methoxyamine hydrochloride | Derivatization reagent | Protects carbonyl groups prior to silylation in GC-MS [40] |

| N-Methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl) trifluoroacetamide (MSTFA) | Silylation reagent | Adds trimethylsilyl groups to polar functionalities for GC-MS [40] |

| Retention Index Markers | Chromatographic calibration | n-Alkanes (C8-C40) for retention index calculation in GC-MS [40] |

| Internal Standards | Quality control and quantification | Stable isotope-labeled compounds for both GC-MS and LC-MS [40] |

| Solid Phase Extraction | Sample clean-up | Removes lipids and interfering compounds prior to analysis [40] |

Applications in Plant Chemical Ecology and Drug Discovery

Ecometabolomics applications have expanded dramatically with technical advancements, moving from targeted approaches to comprehensive untargeted profiling [37]. In plant chemical ecology, these tools enable researchers to:

- Decipher plant-insect interactions by identifying metabolites involved in defense and attraction [41]

- Understand plant responses to environmental stressors including pollutants, nanoparticles, and changing nutrient conditions [38]

- Map metabolic adaptations to abiotic factors like temperature, water availability, and soil conditions [37]

- Identify chemical markers for species interactions and ecosystem functioning [37]

In drug discovery from medicinal plants, metabolomics bridges traditional knowledge and modern science by:

- Identifying bioactive compounds in herbal medicines [42]

- Enabling quality control of plant-derived pharmaceuticals through metabolic profiling [42]

- Supporting sustainable sourcing through green extraction technologies [43]

- Accelerating natural product discovery from biodiverse plant resources [42]

The integration of metabolomics with other omics technologies (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics) provides systems-level insights into the genetic and biochemical bases of ecological interactions and medicinal properties [39].

GC-MS, LC-MS, and untargeted metabolomics have transformed plant chemical ecology from a descriptive science to a predictive one, enabling researchers to decode the complex chemical conversations between plants and their environment. As these technologies continue to evolve, several trends are shaping the future of the field: development of more comprehensive metabolite databases, improved data integration across omics platforms, miniaturization for field-deployable instruments, and advanced computational methods for data analysis and interpretation [39].