Phytochemical Screening of Medicinal Plants: From Traditional Knowledge to Modern Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of phytochemical screening, a critical process for identifying bioactive compounds in medicinal plants.

Phytochemical Screening of Medicinal Plants: From Traditional Knowledge to Modern Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of phytochemical screening, a critical process for identifying bioactive compounds in medicinal plants. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it bridges traditional ethnobotanical knowledge and state-of-the-art analytical methodologies. The content explores the foundational principles of plant secondary metabolites, details established and emerging extraction and analysis techniques, and addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges. It further examines advanced validation strategies, including computational approaches and bioactivity assays, that confirm the therapeutic potential of phytochemicals. By integrating foundational concepts with current innovations, this article serves as a practical guide for advancing natural product research and accelerating the development of plant-derived therapeutics.

The Foundation of Phytochemistry: Understanding Plant Bioactive Compounds and Their Sources

Phytochemicals, the specialized chemical compounds produced by plants, are broadly categorized into primary and secondary metabolites, each serving distinct and vital functions. Primary metabolites are essential for fundamental plant growth and development, whereas secondary metabolites play a crucial role in plant defense and ecological interactions. Within the context of medicinal plant research, the precise screening and characterization of these compounds, particularly the bioactive secondary metabolites, is the cornerstone for drug discovery and development. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide on their definitions, roles, and the advanced analytical methodologies employed to study them, framing this knowledge within the critical practice of phytochemical screening for modern pharmaceuticals.

In plant sciences, the comprehensive study of metabolites—the small molecules produced by plant metabolism—is fundamental to understanding plant physiology, ecology, and their immense pharmacological value. These metabolites are systematically classified into two overarching groups: primary metabolites and secondary metabolites. Primary metabolites, including carbohydrates, lipids, proteins, and amino acids, are ubiquitous across the plant kingdom and are directly indispensable for essential life processes such as energy metabolism, growth, and development [1] [2]. In contrast, secondary metabolites, such as alkaloids, flavonoids, terpenoids, and phenolics, are not involved in primary physiological functions but are critical for the plant's interaction with its environment [1]. They are synthesized as part of the plant's defense mechanism against abiotic stresses (e.g., temperature, light, wounding) and biotic stresses (e.g., microbes, insects, and animals) [2].

The rigorous phytochemical screening of medicinal plants is a foundational approach in natural product research, aimed at detecting and identifying these bioactive compounds [3]. This process is vital for the research and development of pharmaceuticals derived from medicinal plants, which continue to be an area of active and rigorous investigation [4]. The identification and classification of these metabolites not only aid in the authentication of medicinal plant species—a critical step for ensuring the efficacy and safety of plant-derived medicines—but also in the discovery of novel bioactive compounds for drug development [1]. This whitepaper delves into the technical distinctions between primary and secondary metabolites, their specific roles, and the advanced experimental protocols that define their study in contemporary research.

Primary Metabolites: Fundamentals and Functions

Primary metabolites are the fundamental molecules that are directly involved in the normal growth, development, and reproduction of plants. Their presence is universal in all plant cells, and their pathways, such as glycolysis, the Krebs cycle, and photosynthesis, are highly conserved across the plant kingdom. These compounds are the basic building blocks of plant life and are essential for sustaining primary physiological functions.

Table 1: Characteristics of Key Primary Metabolites in Plants

| Metabolite Class | Major Occurrence in Plant Parts | Primary Function in Plant | Role in Human Health & Screening Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrates | Leaves, grains, tubers | Energy source, structural support (cellulose), essential for respiration [1]. | Dietary energy source, dietary fiber for gut health. Screen for purity and yield of extracts. |

| Amino Acids & Proteins | Leaves, roots, seeds | Building blocks of proteins, crucial for plant growth and enzyme function [1] [2]. | Essential amino acids for human nutrition, source of bioactive peptides [2]. |

| Fatty Acids & Lipids | Seeds, fruits, leaves | Vital for membrane structure, energy storage, and signaling molecules [1]. | Source of essential fatty acids (e.g., ω-3), energy storage [2]. |

| Chlorophyll | Leaves | Key pigment for photosynthesis, converting light into chemical energy [1]. | Not directly utilized, but a marker for plant material in processing. |

The significance of primary metabolites in phytochemical screening extends beyond their nutritional value. They can influence the extraction efficiency and pharmacokinetics of secondary metabolites. Furthermore, during the screening process, the analysis of primary metabolite profiles can serve as a tool for the standardization and quality control of medicinal plant materials, ensuring batch-to-batch consistency in herbal preparations [1].

Secondary Metabolites: Diversity and Bioactivity

Secondary metabolites, also referred to as specialized plant metabolites (SPMs), are a large and diverse group of compounds that are not directly involved in the primary processes of growth and development. Instead, they primarily function as defense compounds against herbivores, pathogens, and environmental stressors, and also play roles in plant pollination and seed dispersal [1] [5]. From a pharmaceutical perspective, these compounds are the primary source of pharmacologically active agents in medicinal plants, exhibiting a wide array of biological activities including anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, anticancer, antidiabetic, and antioxidant properties [1] [6].

Table 2: Major Classes of Bioactive Secondary Metabolites in Medicinal Plants

| Metabolite Class | Example Compounds | Medicinal Plant Examples | Documented Biological Activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkaloids | Vinblastine, Vincristine [7] | Catharanthus roseus [7] | Anticancer [1], antimycobacterial [8] |

| Flavonoids | Quercetin, Rutin, Catechin [9] [10] | Euphorbia parviflora [9], Punica granatum [10] | Antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory [1] [10] |

| Phenolic Acids & Tannins | Cinnamic acid, Ellagitannins [9] [10] | Salvia officinalis, Punica granatum [10] | Potent antioxidants, astringents, antimicrobial [9] [10] |

| Terpenoids | Dehydrocostus lactone, Volatile oils [8] [9] | Echinops kebericho [8], Euphorbia parviflora [9] | Antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antifungal [8] [5] |

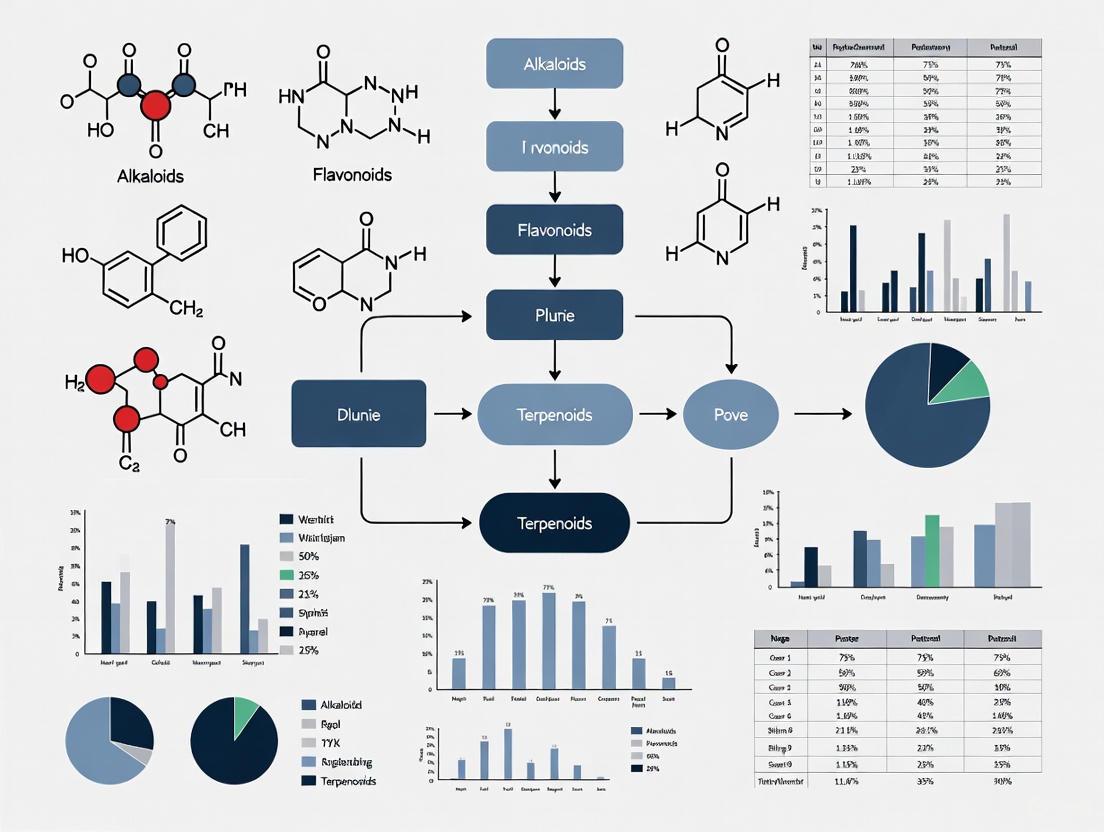

The following diagram illustrates the functional relationships and ecological roles of primary and secondary metabolites in plants:

Figure 1: Functional Roles of Plant Metabolites. Primary metabolites directly sustain fundamental life processes, while secondary metabolites mediate interactions with the environment.

The synthesis of secondary metabolites is often induced by various environmental stresses. When a plant experiences a challenge, its internal redox state changes, triggering the production of these compounds to acclimate to the stress conditions [2]. This inherent bioactivity makes them exceptionally valuable for drug development. For instance, the discovery of artemisinin from Artemisia annua for malaria treatment underscores the potential of mining secondary metabolites from traditionally used medicinal plants [6].

Experimental Protocols for Phytochemical Screening

The phytochemical screening of plant material is a multi-stage process that involves sample preparation, extraction, and a series of qualitative and quantitative analyses to identify and characterize the metabolite profile. The following workflow details a standard protocol.

Sample Preparation and Extraction

The initial steps are critical for preserving the integrity of the phytochemicals.

- Plant Material Collection and Authentication: Fresh plant samples (e.g., leaves, roots, bark) are collected and authenticated by a trained botanist. A voucher specimen is deposited in a herbarium for future reference [8] [9].

- Drying and Grinding: The plant material is washed, and dried in the shade at room temperature to prevent thermal degradation of heat-labile compounds. The dried material is then ground into a fine powder using an electric grinder [8] [9].

- Extraction: The powdered plant material is subjected to extraction. A common method is maceration, where the powder is soaked in a solvent (e.g., methanol, ethanol, chloroform, water) for a set period (e.g., 72 hours) with continuous shaking. The choice of solvent is paramount, as polarity influences the recovery of different metabolite classes. For a broad-spectrum extraction, solvents of varying polarity, such as 100% water, 50% ethanol, and 100% ethanol, are often used sequentially or in parallel [4] [8].

- Filtration and Concentration: The extract is filtered to remove solid residues, often using Whatman filter paper No. 1. The filtrate is then concentrated under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator at controlled temperatures (e.g., 40°C) to obtain the crude extract [8] [9].

Qualitative Phytochemical Analysis

This involves simple chemical tests to detect the presence of major metabolite classes in the crude extract [9].

- Test for Alkaloids: The extract is mixed with 2% H₂SO₄, heated, and filtered. Dragendroff’s reagent is added to the filtrate. The formation of an orange-red precipitate indicates the presence of alkaloids [9].

- Test for Flavonoids: The extract is dissolved in sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution, and then hydrochloric acid (HCl) is added. The solution turning from yellow to colorless confirms the presence of flavonoids [9].

- Test for Tannins: The extract is boiled with distilled water and filtered. A few drops of ferric chloride (FeCl₃) are added to the filtrate. A blackish-green color indicates the presence of tannins [9].

- Test for Terpenoids: The extract is mixed with chloroform and concentrated sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄) is carefully added to form a layer. A reddish-brown interface indicates the presence of terpenoids [9].

- Test for Saponins: The extract is boiled with distilled water. The formation of a persistent froth that lasts for more than three minutes suggests the presence of saponins [9].

Quantitative and Advanced Analytical Techniques

After qualitative confirmation, quantitative analysis is performed to determine the concentration of specific metabolites.

- Total Phenolic Content (TPC): Determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu assay. The extract is reacted with the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent and a saturated sodium carbonate (Na₂CO₃) solution. The absorbance is measured, and the TPC is expressed as milligrams of Gallic Acid Equivalents (GAE) per gram of dry plant weight [9] [10].

- Total Flavonoid Content (TFC): Determined using a colorimetric assay with aluminum chloride. The results are expressed as milligrams of Catechin or Quercetin Equivalents per gram of dry weight [9] [10].

- Chromatographic Techniques: Advanced techniques like High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) are used for separation, identification, and quantification of individual compounds. For example, HPLC can identify and quantify specific compounds like cinnamic acid, quercetin, and catechin in different plant extracts [4] [9]. Untargeted metabolomics using LC-MS or GC-MS is widely recognized as the most appropriate approach for comprehensive analysis of metabolites, enabling the evaluation of qualitative and quantitative alterations in individual metabolites [4].

Figure 2: Phytochemical Screening Workflow. The multi-stage process from plant preparation to advanced analysis and bioactivity testing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table outlines key reagents, solvents, and instruments essential for conducting phytochemical screening research, as derived from the cited experimental protocols.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Phytochemical Screening

| Reagent/Instrument | Technical Function in Phytochemical Screening | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Methanol, Ethanol, Water | Extraction solvents of varying polarity for recovering a wide range of primary and secondary metabolites [4] [8]. | Ultrasonic extraction of 248 medicinal plants with 100% water, 50% ethanol, and 100% ethanol [4]. |

| Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent | Chemical reagent used in the colorimetric quantification of total phenolic content in plant extracts [9] [10]. | Determining total phenols in Euphorbia parviflora and Punica granatum leaf extracts [9] [10]. |

| Dragendroff's Reagent | Precipitating reagent used in qualitative thin-layer chromatography (TLC) or test-tube assays for the detection of alkaloids [9]. | Confirmation of alkaloids in the methanolic extract of Euphorbia parviflora [9]. |

| UHPLC-MS/MS System | (Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry) provides high-resolution separation, identification, and quantification of thousands of metabolites in complex plant extracts [4]. | Feature extraction and metabolite profiling of 744 samples from medicinal plants; enabled detection of 63,944 scans in positive mode [4]. |

| Rotary Evaporator | Instrument for the gentle and efficient removal of solvents from crude plant extracts under reduced pressure and controlled temperature [8]. | Concentration of macerated Echinops kebericho extracts after filtration [8]. |

| DPPH (2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) | Stable free radical compound used in spectrophotometric assays to evaluate the free radical scavenging (antioxidant) activity of plant extracts [9]. | Assessment of antioxidant activity in Euphorbia parviflora extracts [9]. |

The distinction between primary and secondary metabolites is fundamental to medicinal plant research. While primary metabolites are the bedrock of plant life, secondary metabolites represent a vast reservoir of chemical diversity with immense therapeutic potential. The systematic process of phytochemical screening—from traditional qualitative tests to advanced LC-MS-based metabolomics—is indispensable for unlocking this potential. It enables the authentication of plant material, the discovery of novel bioactive compounds, and the development of standardized herbal medicines and modern pharmaceuticals. As technological advances in instrumentation and data analysis (including artificial intelligence) continue to evolve, the field of phytochemical research is poised to make even greater contributions to drug development and personalized medicine, firmly rooted in the chemical wisdom of plants.

Phytochemical screening represents a fundamental research activity for identifying plant-derived bioactive compounds with potential therapeutic applications. In the context of drug discovery, understanding the major classes of secondary metabolites—alkaloids, flavonoids, terpenoids, phenolics, and saponins—provides a critical foundation for developing novel treatments for various diseases. These compounds exhibit diverse biochemical properties and biological activities that can be harnessed for pharmaceutical development. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of these compound classes, their structural characteristics, biosynthesis pathways, biological activities, and established methodologies for their investigation within phytochemical research. The growing resistance to synthetic drugs and the increasing challenges in drug development have renewed scientific interest in these natural products as sources of new chemical entities and lead compounds for therapeutic development.

Comprehensive Classification and Structural Characteristics

Bioactive plant compounds demonstrate remarkable structural diversity, which directly influences their biological activity and potential therapeutic applications. The table below summarizes the core structural features and classification of the major bioactive compound classes.

Table 1: Structural Classification of Major Bioactive Compound Classes

| Compound Class | Basic Structure | Subclasses | Structural Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkaloids | Nitrogen-containing heterocyclic compounds | Pyrrolidines, pyridines, tropanes, pyrrolizidines, isoquinolines, indoles [11] | At least one nitrogen atom in an amine-type structure; often with complex ring systems [11] |

| Flavonoids | C6-C3-C6 skeleton (15-carbon structure) [12] [13] | Flavones, flavonols, flavanones, flavan-3-ols, isoflavones, anthocyanins, chalcones [12] [13] | Two benzene rings (A and B) linked by heterocyclic pyrone ring (C) [13] |

| Terpenoids | Isoprene units (C5H8) [14] | Hemiterpenes (C5), monoterpenes (C10), sesquiterpenes (C15), diterpenes (C20), triterpenes (C30) [14] | Derived from isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) precursors [14] |

| Phenolics | Benzene ring with one or more hydroxyl groups [15] [16] | Phenolic acids, flavonoids, tannins [16] | Hydroxyl substitution patterns critical for activity; range from simple acids to complex polymers [16] |

| Saponins | Triterpenoid or steroid aglycone with sugar moieties [17] | Triterpenoid saponins, steroid saponins | Hydrophobic aglycone (sapogenin) with one or more hydrophilic sugar chains [17] |

Biosynthesis Pathways

The structural diversity of plant bioactive compounds arises from complex biosynthetic pathways that have been elucidated through advanced biochemical and genetic studies. Understanding these pathways is crucial for metabolic engineering and enhancing the production of valuable compounds.

Terpenoid Biosynthesis

Terpenoids originate from two distinct biochemical pathways that operate in different subcellular compartments:

- Mevalonate (MVA) Pathway: Localized predominantly in the cytoplasm and endoplasmic reticulum, this pathway begins with acetyl-CoA and proceeds through mevalonate to produce IPP [14]. The conversion of HMG-CoA to mevalonate, catalyzed by HMG-CoA reductase (HMGR), represents a pivotal rate-limiting step [14].

- Methylerythritol Phosphate (MEP) Pathway: This plastid-localized pathway utilizes pyruvate and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GAP) to produce IPP and DMAPP [14]. The initial condensation reaction catalyzed by DXS (1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase) significantly influences the overall metabolic flux [14].

These pathways demonstrate cross-talk, with frequent exchanges of intermediates between plastids and the cytoplasm, leading to compounds with mixed MVA/MEP origins [14]. Isoprenyl diphosphate synthases (IDSs) then catalyze the formation of geranyl diphosphate (GPP, C10), farnesyl diphosphate (FPP, C15), and geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP, C20), which serve as precursors for the diverse array of terpenoids [14].

Flavonoid and Saponin Biosynthesis

Flavonoids share a common biosynthetic origin with phenolic compounds through the shikimate and phenylpropanoid pathways, producing the characteristic C6-C3-C6 skeleton [12]. The structural diversity arises from modifications including hydroxylation, glycosylation, and methylation.

Saponin biosynthesis involves the cyclization of 2,3-oxidosqualene by oxidosqualene cyclases (OSCs) to produce triterpene skeletons [17]. This is followed by oxidative modifications catalyzed by cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (CYP450s) and glycosylation by UDP-dependent glycosyltransferases (UGTs) [17]. The extensive functional diversity of saponins results from the combinatorial actions of these enzyme families.

Biological Activities and Mechanisms of Action

The therapeutic potential of bioactive plant compounds stems from their diverse mechanisms of action and interactions with cellular targets. The quantitative bioactivity data for these compound classes are summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Documented Biological Activities and Potencies of Bioactive Compounds

| Compound Class | Bioactivities | Molecular Targets | Reported Efficacy/IC50 Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkaloids | Analgesic, stimulant, local anesthetic, antimalarial, muscle relaxant [11] | Opioid receptors, ion channels, neurotransmitter systems [11] | Morphine (potent narcotic), quinine (antimalarial), vincristine (chemotherapeutic) [11] |

| Flavonoids | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic, anticancer, neuroprotective [12] [13] | COX, LOX, NF-κB, PI3K/Akt, α-amylase, α-glucosidase [12] [13] | Fluorinated chalcone derivatives: α-glucosidase inhibition (IC50 = 63.04 μg/mL) [18] |

| Terpenoids | Anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antiviral, insecticidal [14] | Various enzyme systems, membrane receptors [14] | Glycyrrhizin (anti-inflammatory), artemisinin (antimalarial) [17] |

| Phenolics | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, cardioprotective, neuroprotective [15] [16] | Nrf2–ARE, NF-κB pathways, radical scavenging [15] | O. gratissimum DPPH assay (IC50 = 11.744 μg/mL) [19] |

| Saponins | Anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, anticancer, antiviral [17] [20] | Immune cell functions, membrane cholesterol [20] | Heinsiagenin A (potent immunosuppressant) [20] |

Molecular Mechanisms of Action

The bioactivities of these compounds are mediated through specific molecular mechanisms:

- Anti-inflammatory Effects: Flavonoids such as fisetin, quercetin, and rutin inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokine production (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8) and reduce activation of the transcription factor NF-κB [13]. Similarly, triterpenoid saponins like heinsiagenin A exhibit significant immunosuppressive activity by inhibiting T cell proliferation [20].

- Antioxidant Activity: Phenolic compounds exert antioxidant effects through radical scavenging, metal chelation, and singlet oxygen-quenching activities [15]. Their structure-activity relationship demonstrates that hydroxylation and methoxylation patterns critically impact antioxidant strength [15].

- Antidiabetic Mechanisms: Flavonoids and chalcones regulate glucose metabolism through multiple pathways, including inhibition of α-glucosidase and α-amylase, regulation of glucose transporters, and enhancement of insulin signaling [13]. Chalcone derivatives have demonstrated significant α-glucosidase inhibitory activity with IC50 values of 63.04 μg/mL [18].

- Anticancer Potential: Flavonoids modulate angiogenesis, inflammation, oxidative stress, and induce apoptosis through regulation of key cellular signaling pathways including PI3K/Akt, Wnt/β-catenin, and MAPK [13]. Terpenoid compounds similarly exhibit antiproliferative effects against various cancer cell lines.

Phytochemical Screening Methodologies

Phytochemical screening employs standardized experimental protocols for the extraction, identification, and bioactivity assessment of plant compounds. The workflow below illustrates a comprehensive approach to phytochemical investigation.

Standardized Experimental Protocols

Phytochemical Screening Protocol (Qualitative)

Objective: To detect major classes of bioactive compounds in plant extracts [19].

Materials:

- Plant material (dried and powdered)

- Methanol, ethanol, water (extraction solvents)

- Test reagents: Wagner's reagent (alkaloids), 1% FeCl3 solution (phenolics), Shinoda test reagents (flavonoids), Foam test solution (saponins) [19]

Procedure:

- Prepare plant extracts using decoction or percolation methods with appropriate solvents [19].

- For alkaloid detection: Treat extract with Wagner's reagent; formation of reddish-brown precipitate indicates presence [19].

- For flavonoid detection: Perform Shinoda test; addition of magnesium ribbon and concentrated HCl produces pink-red color [19].

- For phenolic detection: Treat with 1% FeCl3; blue-green color indicates phenolics [19].

- For saponin detection: Shake extract vigorously with water; persistent foam indicates saponins [19].

Antioxidant Activity Assessment (DPPH Assay)

Objective: To evaluate free radical scavenging activity of plant extracts [19].

Materials:

- Plant extracts

- DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) solution (0.1 mM in methanol)

- Ascorbic acid (standard antioxidant)

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer

- Microplates or test tubes

Procedure:

- Prepare serial dilutions of plant extracts in methanol.

- Mix 1 mL of each dilution with 1 mL of DPPH solution.

- Incubate in dark for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Measure absorbance at 517 nm against blank.

- Calculate percentage inhibition using formula: % Inhibition = [(Acontrol - Asample)/A_control] × 100 [19].

- Determine IC50 values (concentration providing 50% inhibition) using linear regression analysis.

Antimicrobial Assessment (Broth Dilution Method)

Objective: To determine minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of plant extracts against pathogenic microorganisms [19].

Materials:

- Plant extracts

- Microbial strains (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa)

- Mueller-Hinton broth

- Sterile 96-well microtiter plates

- Incubator

Procedure:

- Prepare serial two-fold dilutions of plant extracts in broth medium.

- Standardize microbial inoculum to 0.5 McFarland standard (~1.5 × 10^8 CFU/mL).

- Add standardized inoculum to each well containing extract dilutions.

- Include growth control (inoculum without extract) and sterility control (broth only).

- Incubate at appropriate temperature for 18-24 hours.

- Determine MIC as the lowest concentration showing no visible growth [19].

- Calculate fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI) for combination studies.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Phytochemical Screening

| Reagent/Material | Application | Function | Example Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| UPLC-QTOF-MS [19] | Compound separation and identification | High-resolution separation and accurate mass determination for metabolite profiling | Identification of rosmarinic acid, cirsimaritin, and kaempferol derivatives in plant extracts [19] |

| DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) [19] | Antioxidant activity assessment | Free radical compound that changes color when reduced by antioxidants | Quantitative assessment of free radical scavenging activity in plant extracts [19] |

| Mueller-Hinton Broth [19] | Antimicrobial assays | Standardized medium for determining minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) | Evaluation of antibacterial activity against S. aureus, E. coli, and P. aeruginosa [19] |

| Wagner's Reagent [19] | Alkaloid detection | Precipitating agent for alkaloids in qualitative screening | Formation of reddish-brown precipitate indicating alkaloid presence [19] |

| CYP450 Enzymes [17] | Terpenoid modification | Oxidative modification of terpene skeletons in saponin biosynthesis | Hydroxylation of β-amyrin at C-24 position by CYP93E1 in soyasaponin biosynthesis [17] |

| UDP-sugars [17] | Glycosylation reactions | Sugar donors for glycosyltransferases in saponin biosynthesis | Addition of glucose, galactose, or other sugars to triterpene aglycones [17] |

Structure-Activity Relationships

The biological activity of bioactive compounds is intrinsically linked to their structural features. Understanding these relationships enables rational design of optimized derivatives with enhanced therapeutic properties.

- Phenolic Compounds: Structure-activity studies demonstrate that hydroxyl group position significantly influences bioactivity. Ortho-hydroxybenzoic acid increases casein solubility, while meta- and para-hydroxybenzoic acids show no significant effect [16]. Compounds with larger molecular weights and more phenolic hydroxyl groups (tannic acid, ellagic acid, myricetin) exhibit stronger binding to proteins compared to simpler phenolics [16].

- Flavonoids: The catechol (3',4'-dihydroxy) structure in the B-ring enhances antioxidant activity, while the 2,3-double bond in conjugation with a 4-oxo function in the C-ring is crucial for free radical scavenging [13]. Glycosylation patterns significantly influence bioavailability and biological activity [12].

- Terpenoid Saponins: The number, composition, and position of sugar chains attached to the triterpene scaffold significantly impact biological activity, taste, and bioabsorbability [17]. Structural modifications through biocatalysis can enhance therapeutic potential.

Phytochemical screening of medicinal plants continues to provide valuable compounds with significant therapeutic potential. The major classes of bioactive compounds—alkaloids, flavonoids, terpenoids, phenolics, and saponins—demonstrate diverse chemical structures and biological activities that can be exploited for drug development. Advanced analytical techniques such as UPLC-QTOF-MS have significantly enhanced our ability to characterize complex plant metabolites and identify novel bioactive compounds. Standardized methodologies for assessing bioactivities, including antioxidant, antimicrobial, and enzyme inhibition assays, provide critical data for evaluating therapeutic potential. Future research should focus on exploring synergistic interactions between different phytochemical classes, investigating underutilized plant species, and employing bioassay-guided fractionation to isolate novel active constituents. The integration of traditional knowledge with modern phytochemical approaches remains a promising strategy for expanding our pharmacopoeia with effective plant-derived therapeutics.

Ethnobotany, the study of the complex relationships between cultures and their use of plants, provides a valuable knowledge base for accelerating modern drug discovery. For millennia, diverse civilizations have relied on traditional remedies derived from plants to treat a wide range of conditions, building a substantial repository of information on biologically active plant species through empirical observation [21]. The core premise of using ethnobotany as a guide lies in the non-random nature of traditional plant selection—specific plants have been consistently used for particular therapeutic indications across different cultures and geographical regions, suggesting a validated bioactivity that transcends cultural boundaries [21]. Modern systematic analyses confirm that taxonomically related medicinal plants tend to be used for treating similar indications, and this correlation is supported by shared bioactive phytochemicals among congeners [21]. This convergence of traditional use across cultures provides high-confidence hypotheses for prioritizing plants for phytochemical screening, offering a strategic advantage over random collection approaches.

The interdisciplinary field of ethnopharmacology has emerged to bridge traditional knowledge and modern science, exploring the biologically active agents from plants, minerals, animals, fungi, and microbes used in traditional medicine [22]. This approach has gained significant traction in recent years, with the World Health Organization (WHO) launching a new Global Traditional Medicine Strategy (2025–2034) to advance the contribution of evidence-based traditional medicine to global health [23]. Despite this recognition, less than 1% of global health research funding is dedicated to traditional medicine, highlighting both the challenge and opportunity in this field [23]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive framework for leveraging ethnobotanical knowledge to design targeted screening strategies in phytochemical research, offering methodologies, protocols, and visualization tools to maximize the efficiency of natural product discovery.

Methodological Framework: From Ethnobotanical Data to Targeted Screening

Systematic Documentation of Traditional Knowledge

The initial phase in ethnobotanically-guided screening involves the systematic collection and documentation of traditional knowledge. This process must be conducted with ethical consideration, respecting indigenous rights and ensuring equitable benefit-sharing [23]. Proper documentation should capture not only the plant species used but also the specific plant parts, preparation methods, administration routes, and intended therapeutic applications. For example, detailed ethnobotanical studies of Urtica simensis in Ethiopia document that leaves are roasted and consumed with injera for gastritis, fresh leaf juice is applied topically for wounds, and crushed roots are mixed with water for malaria treatment [24]. This granular information provides critical insights for experimental design.

Standardized Data Collection Parameters:

- Plant Identification: Botanical name, family, genus, species, voucher specimen details

- Traditional Use: Specific ailments treated, method of preparation, dosage forms

- Geographical Context: Location of collection, cultural group using the remedy

- Temporal Factors: Season of collection, stage of plant growth

- Cultural Significance: Exclusive vs. shared knowledge, specialized practitioners

Cross-Cultural Validation Analysis

A powerful method for prioritizing plant candidates involves analyzing cross-cultural ethnobotanical patterns. Large-scale systematic analyses reveal that when different cultures use taxonomically related plants for similar therapeutic purposes, despite being geographically separated, this convergence significantly increases confidence in their efficacy [21]. For instance, Tinospora cordifolia (native to India) and Tinospora bakis (from Nigeria) are both used to treat liver diseases and jaundice, while Glycyrrhiza uralensis (Asia) and Glycyrrhiza lepidota (North America) are both used for cough and sore throat [21]. This cross-cultural validation serves as a natural filter for identifying high-priority candidates for targeted screening.

Table 1: Quantitative Analysis of Ethnobotanical Correlations Across Taxonomic Levels

| Taxonomic Relationship | Correlation in Medicinal Use | Statistical Significance | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Congeneric plant pairs | Higher correlation | p < 0.001 | Literature dataset [21] |

| Same family plant pairs | Moderate correlation | p < 0.01 | Literature dataset [21] |

| Random plant pairs | Lower correlation | Not significant | Literature dataset [21] |

| Geographically close congeners | Slightly higher correlation | p < 0.05 | Ethnobotanical databases [21] |

| Geographically distant congeners | Significant correlation | p < 0.01 | Ethnobotanical databases [21] |

Experimental Protocols for Targeted Phytochemical Screening

Ethnobotany-Guided Plant Selection and Extraction

Protocol Objective: To systematically select plant materials based on ethnobotanical data and prepare extracts for targeted biological screening.

Materials and Reagents:

- Plant materials collected and identified according to ethnobotanical records

- Solvents: methanol, ethanol, ethyl acetate, hexane, water

- Extraction apparatus: Soxhlet extractor, ultrasonic bath, rotary evaporator

- Drying equipment: freeze dryer, vacuum oven

- Storage: amber glass vials, desiccator

Procedure:

- Plant Material Preparation: Select plant parts specifically documented in traditional use (e.g., leaves, roots, bark). Prepare voucher specimens and deposit in herbarium. Dry plant material at 40°C and grind to fine powder (20-80 mesh).

- Sequential Extraction: Perform sequential extraction using solvents of increasing polarity (hexane → ethyl acetate → methanol → water) to fractionate compounds based on polarity. Use 1:10 plant material-to-solvent ratio.

- Extraction Techniques: Employ appropriate extraction methods: Soxhlet extraction for non-polar solvents, maceration or ultrasonic-assisted extraction for polar solvents at room temperature to preserve thermolabile compounds.

- Extract Concentration: Concentrate extracts under reduced pressure at 40°C using rotary evaporator. Aqueous extracts may be freeze-dried.

- Yield Calculation: Determine extraction yield using formula: Yield (%) = (Weight of extract / Weight of plant material) × 100.

- Storage: Store extracts at -20°C in airtight containers protected from light. Record detailed documentation of extraction parameters.

This targeted approach differs from random screening by focusing on specific plant parts and extraction methods aligned with traditional preparation, potentially enriching for bioactive compounds [24] [22].

High-Throughput Phytochemical Screening and Compound Identification

Protocol Objective: To rapidly screen ethnobotanically-selected extracts for bioactive compounds and characterize identified actives.

Materials and Reagents:

- HPLC-MS system (e.g., UHPLC-QTOF-MS)

- GC-MS system with appropriate columns

- NMR spectrometer (400 MHz or higher)

- Cell cultures for bioassays

- Microtiter plates for high-throughput screening

- Standard phytochemical reference compounds

Procedure:

- Initial Phytochemical Profiling:

- Perform preliminary phytochemical screening for major compound classes: alkaloids (Dragendorff's test), flavonoids (Shinoda test), terpenoids (Salkowski test), tannins (ferric chloride test), saponins (foam test).

- Use TLC for rapid fingerprinting of extracts (silica gel plates, appropriate mobile phases, detection under UV 254/365 nm and specific spraying reagents).

Advanced Chemical Characterization:

- HPLC-MS Analysis: Use reverse-phase C18 column, gradient elution with water-acetonitrile or water-methanol with 0.1% formic acid. Monitor at 200-400 nm. MS parameters: ESI positive/negative mode, mass range 50-2000 m/z.

- GC-MS Analysis: For volatile compounds, use DB-5MS column, temperature programming from 60°C to 300°C. Electron impact ionization at 70 eV, mass range 40-600 m/z.

- NMR Spectroscopy: Prepare samples in deuterated solvents (CDCl₃, DMSO-d₆, CD₃OD). Record ¹H, ¹³C, and 2D NMR spectra (COSY, HSQC, HMBC) for structure elucidation.

Bioactivity-Guided Fractionation:

- Subject active extracts to bioassay-guided fractionation using column chromatography (silica gel, Sephadex LH-20, MCI gel) and preparative HPLC.

- Test fractions for targeted biological activity (antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, etc.) using relevant in vitro assays.

- Continue isolation and purification until pure active compounds are obtained.

Structure Elucidation:

- Determine structure of pure compounds using spectral data (MS, NMR, IR, UV).

- Compare with literature data and authentic standards when available.

- Use X-ray crystallography for complete structural confirmation where possible.

Table 2: Key Phytochemical Classes and Their Screening Methodologies

| Phytochemical Class | Primary Screening Methods | Characterization Techniques | Bioactivities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkaloids | Dragendorff's test, TLC | HPLC-UV/MS, NMR, X-ray | Antimicrobial, anticancer, neurological effects [25] |

| Flavonoids | Shinoda test, AlCl₃ test | LC-MS, NMR, UV spectroscopy | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer [26] |

| Terpenoids | Salkowski test, TLC | GC-MS, NMR, IR | Antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, anticancer [25] |

| Phenolic compounds | Ferric chloride test, Folin-Ciocalteu | HPLC-DAD/MS, NMR | Antioxidant, cardioprotective, antidiabetic [24] |

| Saponins | Foam test, hemolysis test | LC-MS, NMR, hydrolysis | Antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory [26] |

Computational Integration and Visualization

Workflow for Ethnobotanically-Guided Drug Discovery

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow from ethnobotanical data collection to lead compound identification:

Integration of Computational Approaches in Ethnobotany-Guided Screening

Modern phytochemical research increasingly incorporates computational methods to enhance the efficiency of ethnobotanically-guided discovery. In silico docking and molecular dynamics simulations allow researchers to predict interactions between phytochemicals and biological targets, prioritizing compounds for experimental validation [25] [22]. Network pharmacology approaches construct signaling and interaction networks based on observed or deduced interactions of compounds with cellular mechanisms, helping to understand complex synergistic effects often present in traditional herbal preparations [22]. Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling interrelates phytochemical properties with diverse physiological activities such as antimicrobial or anticancer effects, enabling prediction of bioactivity based on chemical structure [25].

These computational methods have evolved the discovery paradigm—where traditionally the starting point was the plant itself, identified through ethnobotanical research, modern approaches can begin with active substances pinpointed by computational methods, followed by identification of plants containing these ingredients through existing ethnobotanical knowledge [22]. This reverse approach demonstrates how ethnobotanical databases and computational chemistry can be synergistically integrated for more efficient discovery workflows.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Databases for Ethnobotany-Guided Screening

| Tool/Database | Type/Format | Primary Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dr. Duke's Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases | Digital database | In-depth plant, chemical, bioactivity, and ethnobotany searches | Facilitates correlation of traditional use with phytochemical composition [27] |

| HPLC-MS with UV/DAD | Instrumentation | Separation, identification, and quantification of phytochemicals | Chemical fingerprinting of active extracts, compound identification [22] |

| NMR Spectrometer (400 MHz+) | Instrumentation | Structural elucidation of pure compounds | Determination of molecular structure and stereochemistry [25] |

| Traditional Medicine Databases (TradiMed, TCMID) | Digital database | Documentation of traditional uses of medicinal plants | Cross-referencing ethnobotanical applications [28] |

| In silico Docking Software (AutoDock, Schrödinger) | Computational tool | Prediction of ligand-target interactions | Virtual screening of phytochemical libraries against disease targets [25] |

| Cell-based Assay Systems | Biological reagents | Evaluation of bioactivity and toxicity | Assessment of therapeutic potential and safety profiling [22] |

Ethnobotany provides a validated, time-tested framework for prioritizing plant species in phytochemical screening programs. The systematic methodologies outlined in this technical guide—from rigorous ethnobotanical data collection and cross-cultural analysis to modern computational integration—enable researchers to efficiently bridge traditional knowledge and contemporary drug discovery. The convergent use of taxonomically related plants across different cultures for similar therapeutic indications offers a powerful filter for identifying biologically active species with higher probability of success [21]. As technological advances in analytical chemistry, computational screening, and bioassay systems continue to evolve, the integration of ethnobotanical wisdom with modern scientific methods will undoubtedly yield novel therapeutic agents while preserving and validating traditional knowledge systems. This approach represents not merely a screening strategy but a paradigm shift in natural product research that respects indigenous knowledge while applying rigorous scientific validation.

Medicinal plants represent a cornerstone in the global healthcare landscape, serving as a vital source of therapeutic agents and leading compounds for drug discovery. The global medicinal herbs market, estimated at USD 227.65 billion in 2025, is projected to reach USD 478.93 billion by 2032, exhibiting a robust compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 11.21% [29]. This growth is fueled by rising consumer preference for natural and organic healthcare solutions, particularly for chronic and lifestyle-related conditions, alongside increasing validation of traditional medicine through scientific research. Within modern drug development, medicinal plants provide indispensable raw materials for pharmaceutical synthesis and innovative lead compounds, with approximately 25% of modern drugs derived from plant sources [30]. This whitepaper examines the integral role of medicinal plants within contemporary healthcare systems and drug discovery pipelines, with particular emphasis on advanced phytochemical screening methodologies that validate traditional knowledge and unlock novel therapeutic applications.

Historical Context and Traditional Knowledge Systems

The use of medicinal plants extends deep into human history, forming the foundation of traditional medical systems worldwide. Traditional medicine is officially defined as "the sum total of the knowledge, skills and practices based on the theories, beliefs and experiences indigenous to different cultures, whether explicable or not, used in the maintenance of health, as well as in the prevention, diagnosis, improvement or treatment of physical and mental illnesses" [31]. According to the World Health Organization, approximately 65% of the world's population relies on traditional medicine as their primary healthcare modality [30], with this dependence being particularly pronounced in rural communities lacking proper healthcare infrastructure [30].

Ethnobotany and ethnopharmacology serve as crucial disciplines bridging traditional knowledge and modern scientific validation. These fields systematically document how indigenous cultures use plants for medicinal, nutritional, and cultural purposes, combining cultural wisdom with scientific inquiry to identify bioactive compounds with therapeutic potential [32]. Quantitative ethnobotanical studies employ various indices to quantify the importance of specific medicinal plants:

- Informant Consensus Factor (ICF) measures homogeneity of informant knowledge, with highest values (0.87) documented for wound healing applications [30].

- Use Value (UV) indicates relative importance of specific plants, with highest values documented for Conyza canadensis and Cuscuta reflexa (0.58 each) [30].

- Fidelity Level (FL) shows percentage of informants mentioning use for specific purpose, with Azadirachta indica reaching 93.4% for blood purification [30].

Table 1: Quantitative Ethnobotanical Indices for Selected Medicinal Plants

| Plant Species | Informant Consensus Factor (ICF) | Use Value (UV) | Fidelity Level (FL) | Primary Traditional Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acacia nilotica | 0.85 (skin/nail disorders) | 0.95 | 91.1% | Sexual disorders |

| Azadirachta indica | 0.85 (skin/nail disorders) | 0.91 | 93.4% | Blood purification |

| Triticum aestivum | 0.85 (skin/nail disorders) | 0.95 | N/R | General health |

| Conyza canadensis | 0.87 (wound healing) | 0.58 | N/R | Wound healing |

| Cuscuta reflexa | 0.87 (wound healing) | 0.58 | N/R | Wound healing |

Phytochemical Screening: Methodologies and Protocols

Plant Material Collection and Extraction

Standardized protocols for plant material collection and extraction form the foundation of reproducible phytochemical research. The following workflow outlines the essential steps from plant collection to crude extract preparation:

Detailed Protocols:

- Plant Authentication: Botanical identification by qualified taxonomists with voucher specimen deposition in recognized herbaria [33] [30].

- Processing: Plant materials carefully washed with water, trimmed to appropriate size, and air-dried in shade for approximately two weeks to preserve thermolabile compounds [33].

- Extraction: Cold maceration at room temperature for 72 hours with intermittent shaking using solvents of varying polarity (typically 80% methanol) [33].

- Concentration: Filtration through Whatman No. 1 filter paper followed by evaporation under reduced pressure at 40°C using rotary evaporator [33].

- Preservation: Lyophilization at -40°C and 200 mBar vacuum pressure with storage in airtight containers at 4°C until use [33].

Qualitative Phytochemical Screening

Primary phytochemical screening employs standardized chemical tests to detect major classes of bioactive compounds. The following table outlines common screening protocols:

Table 2: Standard Phytochemical Screening Protocols

| Target Compound | Test Name | Procedure | Positive Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkaloids | Mayer's Test | Add dilute HCl to extract + Mayer's reagent | Yellowish-white precipitate |

| Flavonoids | Sulfuric Acid Test | Add concentrated H₂SO₄ to extract | Orange color formation |

| Phenols | Ferric Chloride Test | Add 10% FeCl₃ to extract + water | Blue or green color |

| Glycosides | Keller-Killiani Test | Add glacial acetic acid + FeCl₃ + H₂SO₄ | Deep blue color at interface |

| Tannins | Alkaline Reagent Test | Add NaOH to extract | Yellow to red color change |

| Free Anthraquinones | Borntrager's Test | Heat with chloroform, filter, add ammonia | Bright pink in aqueous layer |

| Saponins | Foam Test | Shake extract with distilled water | Stable foam formation |

| Terpenoids | Salkowski Test | Add chloroform + concentrated H₂SO₄ | Reddish-brown interface |

Advanced Analytical Techniques

Sophisticated instrumentation enables precise identification, quantification, and characterization of bioactive phytochemicals:

Chromatographic Techniques:

- High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC): Separation and quantification of complex phytochemical mixtures.

- Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC): Rapid screening and preliminary separation.

- Gas Chromatography (GC): Volatile compound analysis, typically coupled with mass spectrometry (GC-MS) [34].

Spectroscopic Methods:

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: Structural elucidation of purified compounds.

- Mass Spectrometry (MS): Molecular weight determination and structural characterization.

- Infrared (IR) Spectroscopy: Functional group identification [32].

Bioactivity Assessment: Integrated Methodological Approaches

Antimicrobial Evaluation Protocols

Antimicrobial activity assessment employs standardized microbiological techniques with the following experimental workflow:

Detailed Methodologies:

Agar Well Diffusion [33]:

- Plates inoculated with standardized microbial suspensions (1 × 10⁷ CFU/ml for bacteria, 1 × 10⁶ spores/ml for fungi).

- Wells (8-mm diameter) created with sterile cork borer and filled with 100 µL test extract.

- Positive controls: ciprofloxacin (5 µg) for bacteria, amphotericin B (12.5 µg) for fungi.

- Negative control: 1% DMSO.

- Incubation at 37°C for 18-24h (bacteria) or 28°C for 48h (fungi).

- Zone diameters measured in millimeters.

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) [33]:

- Broth microdilution in 96-well plates with two-fold serial dilutions.

- Inoculation with standardized suspensions (5 × 10⁵ CFU/ml for bacteria, 5 × 10⁴ spores/ml for fungi).

- Addition of 0.2 mg/ml 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) as growth indicator.

- Incubation at 37°C for 30 minutes.

- MIC defined as lowest concentration showing no pink color formation.

Minimum Bactericidal/Fungicidal Concentration (MBC/MFC) [33]:

- Subculturing from wells showing no growth in MIC assay onto fresh agar media.

- Incubation for 24h at appropriate temperatures.

- MBC/MFC defined as lowest concentration yielding no visible growth on subculture.

Neuropharmacological Evaluation

Integrated approaches combining in vitro, in silico, and in vivo methods provide comprehensive assessment of neuropharmacological potential:

In Vivo Behavioral Models [34]:

- Open field test (locomotor activity and exploration)

- Light-dark box test (anxiety-like behavior)

- Elevated plus maze test (anxiety)

- Tail suspension test (antidepressant activity)

- Forced swim test (antidepressant activity)

- Y-maze test (spatial memory)

- Hole cross test (exploratory behavior)

- Social interaction test (social behavior)

In Silico Molecular Docking [34]:

- Target receptors: hMAO A and hMAO B for neurological disorders.

- Compounds identified through GC-MS analysis.

- Docking studies to predict binding affinity and interactions.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Phytochemical and Bioactivity Studies

| Reagent/Material | Application | Function | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 80% Methanol | Extraction | Medium-polarity solvent for broad-spectrum compound extraction | Cold maceration of plant materials [33] |

| Mayer's Reagent | Phytochemical screening | Alkaloid detection through precipitate formation | Qualitative alkaloid screening [33] |

| Mueller-Hinton Agar | Microbiology | Standardized medium for antimicrobial susceptibility testing | Agar well diffusion assays [33] |

| Sabouraud Dextrose Agar | Mycology | Fungal culture and antifungal susceptibility testing | Antifungal activity assessment [33] |

| 2,3,5-Triphenyltetrazolium Chloride (TTC) | MIC determination | Metabolic activity indicator (colorimetric) | Broth microdilution assays for MIC determination [33] |

| Ciprofloxacin | Antimicrobial controls | Positive control for antibacterial assays | Reference standard in antibacterial testing [33] |

| Amphotericin B | Antifungal controls | Positive control for antifungal assays | Reference standard in antifungal testing [33] |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Solvent control | Vehicle for compound dissolution | Negative control in bioactivity assays [33] |

Current Research Trends and Global Impact

Bibliometric Analysis and Research Evolution

Analysis of over 100,000 publications in the Scopus database reveals dynamic evolution in medicinal plant research [31]. Global publications have increased steadily from 1960 to 2001, accelerated rapidly until 2011 (peaking at ~6,200 publications annually), and subsequently stabilized at approximately 5,000 publications per year [31]. Research distribution across subject categories demonstrates the interdisciplinary nature of this field:

- Pharmacology, Toxicology and Pharmaceutics: 27.1%

- Medicine: 23.8%

- Biochemistry, Genetics and Molecular Biology: 16.7%

- Agricultural and Biological Sciences: 11%

- Chemistry: 8.7% [31]

Global research leadership has shifted over time, with China leading from 1996-2010, India leading from 2010-2016, and China regaining dominance thereafter [31]. Secondary tier research nations include Iran, Brazil, USA, South Korea, and Pakistan, all showing sustained growth between 200-400 publications annually [31].

Market Dynamics and Therapeutic Applications

The global medicinal herbs market demonstrates robust growth dynamics with several key segments:

Table 4: Medicinal Herbs Market Segmentation and Projections (2025)

| Segment Category | Leading Segment | Projected Market Share/Value | Growth Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Herb Type | Ginseng | 16.6% revenue share in 2025 | Adaptogenic properties, cognitive enhancement |

| Product Form | Raw/Whole Herbs | >25% market share in 2025 | Traditional preparation methods, consumer preference |

| Application | Pharmaceuticals | USD 95.8 billion revenue in 2025 | Evidence-based validation, drug development |

| Distribution Channel | Online Retail | Expanding market penetration | E-commerce expansion, product accessibility |

| Geography | Asia-Pacific | >40% revenue share in 2025 | Traditional medicine systems, cultural acceptance |

Key therapeutic applications with substantial clinical validation include:

- Cancer Therapeutics: Plant-derived compounds such as paclitaxel (Pacific yew tree) and etoposide (May apple plant) demonstrate significant antineoplastic activity through mechanisms including cell cycle interference, apoptosis induction, and metastasis inhibition [32].

- Infectious Diseases: With antimicrobial resistance escalating, medicinal plants offer novel antimicrobial compounds. Impatiens rothii root extract demonstrates efficacy against Staphylococcus epidermis (MIC = 4 mg/ml), Salmonella typhimurium (MIC = 3 mg/ml), and Escherichia coli (MIC = 4 mg/ml) [33].

- Neurological Disorders: Mimosa pudica flower extracts show significant anxiolytic and antidepressant activity in neurobehavioral models at doses of 200 mg/kg and 400 mg/kg body weight, comparable to reference drugs Diazepam and Escitalopram [34].

- Metabolic Disorders: Research focus on antidiabetic and anti-inflammatory activities with in vivo validation models [31].

Biotechnology and Sustainable Innovation

Advanced Biotechnological Applications

Biotechnology transforms medicinal plant research through multiple innovative approaches:

- Plant Tissue Culture: Enables large-scale production of bioactive compounds independent of environmental constraints, particularly valuable for endangered species [32].

- Genetic Engineering: Metabolic pathway manipulation to enhance production of target secondary metabolites [32].

- Microbial Symbionts Exploration: Harnessing plant-associated microorganisms (bacteria, fungi, actinomycetes) that influence plant metabolism and enhance synthesis of pharmacologically active compounds [32].

- Marine Biotechnology: Sustainable production of marine-derived compounds through genetic engineering and microbial fermentation, overcoming resource scarcity challenges [32].

Conservation and Sustainability Strategies

With approximately 10% of all vascular plants used medicinally [31], sustainable practices are critical for ecosystem preservation and continued resource availability:

- Cultivation and Domestication: Shifting from wild harvesting to controlled cultivation of high-demand medicinal species.

- Seed Banking: Genetic preservation of medicinally important species.

- Sustainable Farming Practices: Agroforestry and organic cultivation methods.

- Marine Protected Areas: Conservation of marine ecosystems with pharmaceutical potential.

- Responsible Sourcing: Ethical and sustainable supply chain development [32].

Medicinal plants continue to play an indispensable role in modern healthcare and drug discovery, serving as renewable resources for novel therapeutic compounds and validated traditional remedies. The convergence of ethnobotanical knowledge with advanced scientific methodologies—including sophisticated phytochemical screening, integrated bioactivity assessment, and innovative biotechnology applications—positions this field for continued growth and discovery. Future research directions will likely focus on standardization through advanced analytical techniques, clinical validation of traditional applications, sustainable bioproduction, and exploration of underexplored taxa and ecosystems. As the global demand for natural healthcare solutions accelerates, medicinal plants will remain pivotal in addressing emerging health challenges and advancing integrative medical approaches that combine traditional wisdom with contemporary scientific innovation.

Methodologies in Practice: Extraction, Screening, and Isolation Techniques

The preparation of medicinal plants for experimental purposes is an initial and critical step in achieving quality research outcomes within phytochemical screening and drug discovery programs [35]. The core of this process lies in the extraction and subsequent determination of the quality and quantity of bioactive constituents before proceeding with intended biological testing [35]. The concept of preparation involves the proper and timely collection of the plant, authentication, adequate drying, and grinding, followed by extraction, fractionation, and isolation of bioactive compounds where applicable [35]. The primary objective of this guide is to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for selecting extraction solvents based on a polarity gradient, from the non-polar n-hexane to the highly polar water. This strategy is fundamental in the systematic exploration of plant-based pharmaceuticals, enabling the targeted isolation of a diverse spectrum of phytochemicals responsible for various biological activities.

The Polarity Spectrum of Common Extraction Solvents

The choice of solvent, or menstruum, is paramount in extraction efficiency and directly influences which classes of bioactive compounds are isolated [35]. Solvents are selected based on the principle of "like dissolves like," where polar solvents extract polar compounds, and non-polar solvents extract non-polar compounds [35]. During liquid-liquid extraction and fractionation, the conventional strategy involves using a series of miscible solvents, often including water, and proceeding from the least polar to the most polar [35] [36]. This sequential approach ensures a comprehensive extraction of a plant's phytochemical profile.

The following table summarizes key solvents used in medicinal plant extraction, ordered by increasing polarity index, and outlines their primary applications and key considerations for use.

Table 1: Properties and Applications of Common Extraction Solvents Ordered by Increasing Polarity

| Solvent | Polarity Index | Class | Typical Phytochemical Targets | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-Hexane | 0.009 [35] | Non-polar | Waxes, fats, fixed oils, some terpenoids [35] | Effective for non-polar compounds | Highly flammable, volatile [35] |

| Petroleum Ether | 0.117 [35] | Non-polar | Lipids, chlorophyll [35] | Low boiling point | Highly flammable, volatile [35] |

| Diethyl Ether | 0.117 [35] | Non-polar | Alkaloids, terpenoids, coumarins, fatty acids [35] | Miscible with water, low boiling point | Highly volatile, flammable, forms explosive peroxides [35] |

| Ethyl Acetate | 0.228 [35] | Intermediate Polar | Medium-polarity compounds like many flavonoids and phenolics [37] | Polar aprotic, dissolves most polar organics, eco-friendly [37] | - |

| Chloroform | 0.259 [35] | Non-polar | Terpenoids, flavonoids, fats, oils [35] | Colorless, sweet smell, soluble in alcohols | Carcinogenic, sedative properties [35] |

| Dichloromethane | 0.309 [35] | Intermediate Polar | Alkaloids, medium-polarity compounds | - | - |

| Acetone | 0.355 [35] | Intermediate Polar | A wide range of secondary metabolites | - | - |

| n-Butanol | 0.586 [35] | Polar | Glycosides, saponins [35] | - | - |

| Ethanol | 0.654 [35] | Polar | Polar compounds: alkaloids, flavonoids, saponins [35] | Self-preservative (>20%), nontoxic at low concentrations, low heat for concentration [35] | Does not dissolve fats/gums/waxes, flammable [35] |

| Methanol | 0.762 [35] | Polar | Wide range of polar secondary metabolites [35] [33] [34] | Excellent for polar compounds | Flammable, volatile, toxic [35] |

| Water | 1.000 [35] | Polar | Polar compounds: tannins, saponins, polysaccharides, glycosides [35] [38] | Cheap, nontoxic, nonflammable, highly polar [35] | Promotes microbial growth, may cause hydrolysis, high heat required for concentration [35] |

Strategic Application in Extraction and Fractionation

Selection Criteria and Experimental Design

Beyond polarity, several factors must be considered when selecting a solvent for extraction [35]. Selectivity is the ability of the solvent to dissolve the target compound(s) while leaving others behind. Safety is a critical concern, as toxic solvents like chloroform require special handling, whereas ethanol, water, and certain ionic liquids are considered greener alternatives [35] [39]. The boiling point affects the ease of solvent removal post-extraction. The viscosity impacts the rate of penetration into the plant matrix and filtration speed. The cost and availability of the solvent are also practical considerations for research scalability. Finally, the intended use of the final extract dictates solvent choice; for instance, extracts for consumption should ideally be prepared with low-toxicity solvents like water or ethanol [35] [38].

A quintessential application of the polarity-based strategy is in bioassay-guided fractionation [35]. This iterative process begins with creating a crude extract, typically using a solvent of medium polarity like methanol or ethanol, or a binary system like 80% methanol, to capture a broad spectrum of compounds [33]. This extract is then subjected to a biological assay (e.g., antimicrobial, antioxidant). If activity is confirmed, the extract is fractionated using a series of solvents of increasing polarity (e.g., n-hexane → ethyl acetate → n-butanol → water). Each fraction is then tested for biological activity. The most active fraction is selected for further separation and isolation of pure active compounds, which are finally identified using spectroscopic techniques [35].

Advanced Biphasic Solvent Systems

For high-resolution separation techniques like Countercurrent Chromatography (CCC) or Centrifugal Partition Chromatography (CPC), optimized biphasic solvent systems are employed. The HEMWat system, an acronym for n-Hexane/Ethyl Acetate/Methanol/Water, is a widely used and versatile system that leverages the full polarity spectrum [36] [37]. Its components create two immiscible phases: an organic upper phase and an aqueous lower phase. The ratio of these four solvents can be finely adjusted to tune the overall polarity and selectivity of the system, making it suitable for separating a wide range of compounds with varying polarities [37]. The HEAWat (alcohol solvents: methanol, ethanol, isopropanol) and related systems are classified into selectivity groups, which help in selecting the optimal system for separating specific analytes based on their average polarity [36].

Diagram: Workflow for Bioassay-Guided Fractionation Using Polarity-Based Solvent Selection

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Maceration with Methanol-Water for Antimicrobial Screening

This protocol, adapted from studies on Impatiens rothii and Mimosa pudica, is ideal for the initial broad-spectrum extraction of polar to intermediate polarity bioactive compounds [33] [34].

- Plant Material Preparation: Carefully wash the fresh or dried plant material (e.g., roots, leaves, flowers) with clean water. Chop the material into small pieces and allow it to air-dry in the shade at room temperature for approximately two weeks. Pulverize the dried plant material into a fine powder using a mechanical grinder.

- Maceration: Weigh a known quantity of the dried powder (e.g., 100 g) and place it in an airtight glass container. Add a sufficient volume of 80% methanol (v/v) as the menstruum (e.g., 1 L) to ensure complete immersion of the powder. Seal the container and macerate at room temperature for 72 hours with occasional shaking or stirring.

- Filtration and Concentration: After 72 hours, filter the mixture through Whatman No. 1 filter paper or under vacuum to separate the liquid extract (micelle) from the insoluble marc. Collect the filtrate. The marc can be re-macerated with fresh solvent to exhaustively extract the plant material. Combine all filtrates.

- Solvent Removal: Concentrate the combined filtrates under reduced pressure at a controlled temperature (e.g., 40°C) using a rotary evaporator. This yields a concentrated crude extract.

- Lyophilization: For aqueous or hydro-alcoholic extracts, transfer the concentrated extract to a freeze-dryer and lyophilize at -40°C under a strong vacuum until completely dry. The resulting dry powder is the crude extract, which should be stored in an airtight container at 4°C until use [33].

Protocol 2: Sequential Liquid-Liquid Fractionation

This protocol is used to separate the complex crude extract into fractions of different polarity ranges [35].

- Dissolve Crude Extract: Dissolve the dry crude extract (from Protocol 1) in a small volume of the most polar solvent that can hold it in solution, typically water or a water-methanol mixture. Transfer the solution to a separatory funnel.

- Partition with Immiscible Solvent: Add an equal volume of a less polar, immiscible solvent (e.g., n-hexane) to the separatory funnel. Seal the funnel and shake it vigorously, with frequent venting to release pressure. Allow the mixture to stand until the two liquid phases separate completely.

- Separate Phases: The non-polar compounds will partition into the n-hexane (upper organic phase), while the polar compounds will remain in the water (lower aqueous phase). Carefully drain off the lower aqueous layer into a clean flask. Collect the upper n-hexane layer into a separate flask.

- Repeat and Proceed to Next Solvent: The water fraction can now be partitioned against ethyl acetate. Repeat the shaking and separation process. The medium-polarity compounds will move into the ethyl acetate layer (organic phase). Finally, partition the remaining aqueous fraction with n-butanol, which will extract glycosides and saponins, leaving highly polar compounds like polysaccharides in the final aqueous fraction.

- Concentrate Fractions: Concentrate each organic fraction (n-hexane, ethyl acetate, n-butanol) separately using a rotary evaporator. The final aqueous fraction can be lyophilized. This process yields four distinct fractions for subsequent phytochemical and biological analysis [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful phytochemical screening relies on a set of fundamental reagents and materials. The following table lists key items and their functions in the context of extraction and preliminary analysis.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Phytochemical Screening

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| n-Hexane | Extraction of non-polar compounds like fats, oils, and waxes [35]. |

| Ethyl Acetate | Extraction of intermediate polarity compounds; component of advanced biphasic systems like HEMWat [37]. |

| Methanol & Ethanol | General-purpose polar solvents for extracting a wide range of secondary metabolites [35] [33]. |

| Water | Extraction of highly polar compounds such as tannins, saponins, and polysaccharides [35] [38]. |

| Muller-Hinton Agar / Sabouraud Dextrose Agar | Culture media for antibacterial and antifungal susceptibility testing, respectively [33]. |

| Whatman No. 1 Filter Paper | Filtration of plant extracts to separate the micelle from the marc [33]. |

| DPPH (2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) | A stable free radical used in spectrophotometric assays to evaluate the antioxidant activity of extracts [38] [40]. |

| Triphenyltetrazolium Chloride (TTC) | A redox indicator used in broth microdilution assays to visually determine the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) by changing color (pink) in the presence of microbial growth [33]. |

| Mayer's Reagent | A chemical reagent (potassium mercuric iodide) used in qualitative phytochemical screening for the detection of alkaloids [33]. |

A strategic, polarity-driven approach to solvent selection, from n-hexane to water, forms the bedrock of rigorous and reproducible phytochemical research. This methodology enables the systematic exploration of the complex chemical universe within medicinal plants. By understanding the properties of each menstruum and applying them through established protocols like maceration and sequential fractionation, researchers can effectively target, isolate, and identify novel bioactive compounds. This strategy is indispensable for validating traditional medicinal uses and for providing the foundational chemical data required for modern drug development, ultimately bridging the gap between ethnobotanical knowledge and evidence-based pharmaceutical science.

The phytochemical screening of medicinal plants is a fundamental research process for discovering bioactive compounds with therapeutic potential. Extraction, the first critical step, separates these desired plant constituents from the inert cellular matrix. The selection of an appropriate extraction method directly influences the yield, purity, and biological activity of the isolated compounds [35] [41]. Among the various techniques available, three classical methods—maceration, percolation, and Soxhlet extraction—serve as cornerstone processes in natural product research and drug development [42]. These methods, with their distinct mechanisms and applications, provide researchers with versatile tools for initial phytochemical investigation and the procurement of plant extracts for subsequent biological testing [35]. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these three classical extraction techniques, framed within the context of modern phytochemical and drug development workflows.

Principles and Mechanisms of Classical Methods

Maceration Extraction

Maceration is a simple, low-energy extraction process that involves steeping plant material in a solvent for a prolonged period. The dried, powdered plant material (the marc) is placed in a closed container with a selected solvent (the menstruum) and left to stand at room temperature, typically for a minimum of three days [42] [35]. During this time, the solvent penetrates the plant matrix, dissolving the active constituents. The mixture is then filtered, and the solid residue may be pressed to recover any residual extract, maximizing yield [42]. This method is classified as a batch process, where the solvent becomes increasingly concentrated with solutes until equilibrium is reached [41]. Its simplicity and applicability to thermolabile components are its chief advantages, though it often suffers from long extraction times and relatively low efficiency [41] [43].

Percolation Extraction

Percolation is a continuous extraction method that offers greater efficiency than maceration. The process utilizes a specialized funnel-shaped vessel called a percolator. The powdered plant material is first moistened with the solvent and allowed to stand for approximately four hours to ensure proper impregnation [42]. It is then packed into the percolator, and additional solvent is added from the top. The solvent slowly percolates downward through the plant material under gravity, and the resulting extract, or micelle, is collected from the bottom outlet [42] [35]. This continuous flow of fresh solvent prevents the establishment of equilibrium, leading to more exhaustive extraction [41]. A key modern application involves its use in extracting salvianolic acid B from Salvia miltiorrhiza, where it is preferred due to the compound's sensitivity to high temperatures [44].

Soxhlet Extraction

Soxhlet extraction is a continuous, automated method renowned for its high efficiency. Finely powdered plant material is placed in a porous cellulose thimble, which is then positioned in the Soxhlet extractor chamber [42] [45]. The assembly consists of the extractor placed between a round-bottom flask containing the solvent and a condenser. The solvent is heated to boiling, and its vapors travel up to the condenser, where they liquefy [46]. The condensed pure solvent drips onto the sample in the thimble, extracting the desired compounds. When the liquid level in the chamber reaches the top of the siphon tube, the solvent, now enriched with solutes, is siphoned back into the round-bottom flask [42] [47]. This cycle repeats automatically for many hours, ensuring the sample is continuously contacted with fresh solvent, which makes the method exhaustive [45]. However, the prolonged heating makes it unsuitable for thermolabile compounds [45].

Comparative Analysis of Extraction Techniques

The choice between maceration, percolation, and Soxhlet extraction depends on the nature of the plant material, the target compounds, and practical considerations such as time and solvent availability. The table below provides a structured comparison of their core characteristics.

Table 1: Technical comparison of classical extraction methods

| Parameter | Maceration | Percolation | Soxhlet Extraction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Process Nature | Batch, static process [41] | Continuous process [41] | Continuous, cyclic process [45] |

| Principle | Steeping and diffusion [35] | Gravity-driven solvent flow [42] | Solvent reflux and siphoning [46] |

| Temperature | Room temperature [42] | Room temperature (typically) [41] | Boiling point of the solvent [45] |

| Time Required | Long (e.g., 3+ days) [42] | Moderate (e.g., 24 hours) [42] | Long (e.g., 6-24 hours) [45] [47] |

| Solvent Consumption | Large [41] | Large [42] | Moderate, due to recycling [42] [47] |

| Efficiency | Low to moderate [41] | More efficient than maceration [41] | High, exhaustive extraction [42] [45] |

| Suitability | Thermola bile components [41] | Thermola bile components [44] | Stable, heat-resistant compounds [45] |

| Key Advantage | Simple, no specialized equipment [42] | More efficient than maceration [41] | High efficiency, no manual intervention [47] |