Non-Targeted Metabolomics in Plant Chemistry: A Comprehensive Guide from Discovery to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of non-targeted metabolomics and its transformative role in plant chemical analysis.

Non-Targeted Metabolomics in Plant Chemistry: A Comprehensive Guide from Discovery to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of non-targeted metabolomics and its transformative role in plant chemical analysis. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of untargeted approaches for hypothesis-free discovery of novel plant metabolites. The scope covers advanced LC-MS and NMR methodologies, practical applications in crop improvement and stress response studies, and critical troubleshooting for data accuracy and linearity challenges. It further examines validation strategies and comparative analyses with targeted methods, highlighting the direct pathway this technology provides for identifying bioactive plant compounds with therapeutic potential. The integration of these facets offers a complete resource for leveraging plant metabolomics in pharmaceutical and biomedical research.

Unlocking Plant Chemical Diversity: Foundations of Non-Targeted Metabolomics

Background: Non-targeted metabolomics is a powerful analytical strategy for the comprehensive analysis of small molecules in biological systems, enabling the discovery of novel compounds and biochemical pathways without a priori knowledge of sample composition. Aim of Review: This application note delineates the fundamental principles, standardized workflows, and practical protocols for implementing non-targeted metabolomics in plant chemistry research, with emphasis on its hypothesis-generating potential. Key Scientific Concepts: We elaborate the complete workflow from experimental design to data interpretation, highlighting feature-based molecular networking for chemical characterization, quality assurance measures for cross-laboratory reproducibility, and visualization strategies for effective data communication. This approach is particularly valuable for exploring the vast chemical diversity in plants, where much of the metabolome remains uncharacterized.

Non-targeted metabolomics represents a systematic approach for the simultaneous detection and relative quantification of a broad spectrum of metabolites within a biological system [1]. Unlike targeted analyses that focus on predefined compounds, non-targeted methods aim to capture as much of the metabolome as possible, serving as a powerful hypothesis-generating tool for discovering novel compounds, biomarkers, and biochemical pathways [2]. In plant chemistry research, this approach is particularly valuable for investigating the chemical diversity of both primary and specialized metabolites, which enables the comprehensive profiling of wild edible plants, understanding plant-environment interactions, and identifying bioactive compounds with potential pharmaceutical applications [3] [1].

The foundational principle of non-targeted metabolomics lies in its ability to provide a global overview of metabolic phenotypes without prior assumptions about which compounds are significant [2]. This methodology has revealed that our knowledge of food composition has traditionally focused on merely 35-160 molecular components, representing just a small fraction of the tens of thousands of molecules that constitute food, highlighting the vast potential for discovery in plant metabolomics [2]. The integration of high-resolution mass spectrometry with advanced computational analytics has positioned non-targeted metabolomics as an indispensable tool for expanding our understanding of plant chemical diversity and its applications in drug development and nutrition science.

Experimental Design and Workflow

The non-targeted metabolomics workflow encompasses multiple critical stages, from sample preparation to data interpretation, with rigorous quality control essential at each step to ensure reproducible and biologically meaningful results [1]. The workflow can be conceptually divided into wet laboratory and computational components, with visualizations playing a crucial role in data inspection, evaluation, and sharing throughout the process [4].

Table 1: Key Stages in Non-Targeted Metabolomics Workflow

| Stage | Key Activities | Output |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection & Preparation | Homogenization, metabolite extraction using appropriate solvents | Metabolite extract in solution |

| Chromatographic Separation | LC-MS (reversed-phase/HILIC) or GC-MS separation | Chromatograms with resolved peaks |

| Data Acquisition | High-resolution MS and MS/MS in data-dependent or data-independent modes | Raw spectral data files |

| Data Preprocessing | Peak detection, alignment, retention time correction, feature finding | Peak intensity table (feature matrix) |

| Statistical Analysis & Annotation | Multivariate analysis, molecular networking, database searching | Annotated metabolites, significantly altered features |

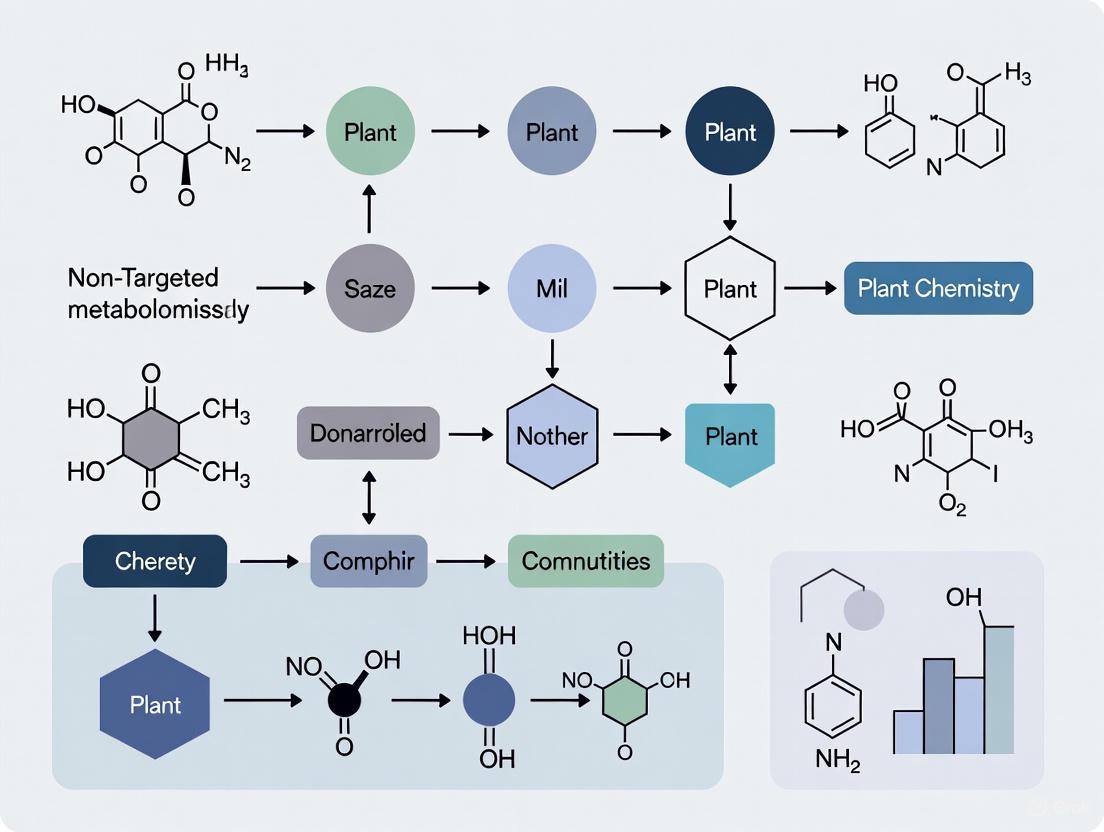

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for non-targeted metabolomics in plant research:

Diagram 1: Non-targeted metabolomics workflow for plant chemistry.

Effective experimental design must account for biological replication, randomization, and incorporation of quality control samples throughout the analytical sequence [2]. Quality control (QC) samples, typically prepared from pooled aliquots of all study samples, are essential for monitoring instrument performance, evaluating technical variance, and correcting for systematic bias [1]. The data preprocessing stage involves noise reduction, retention time correction, peak detection and integration, and chromatographic alignment using specialized software platforms, after which data normalization is performed to reduce technical variation [1].

Core Methodologies and Protocols

Standardized Metabolomics Protocol for Cross-Laboratory Comparison

Recent advancements in non-targeted metabolomics have focused on standardizing protocols to enable data comparability across different laboratories and instrumentation platforms [2]. A validated approach for plant and food matrices involves solid phase extraction (SPE) reverse phase liquid chromatography (RPLC) positive mode electrospray (+ESI) high resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS), which balances broad metabolome coverage with practical implementation across different mass spectrometry platforms [2].

Table 2: Detailed Protocol for Non-Targeted Metabolomics of Plant Samples

| Step | Procedure | Parameters & Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Homogenize lyophilized tissue to fine powder; weigh 50±1mg; add extraction solvent | Methanol:Water (80:20, v/v) with 0.1% formic acid; internal standards |

| Metabolite Extraction | Vortex, sonicate, centrifuge; transfer supernatant; repeat extraction; combine supernatants | 10 min vortex, 15 min sonication, 10 min centrifugation at 4°C |

| Sample Analysis | Inject onto LC-MS system; data acquisition in positive ESI mode with DDA | Reversed-phase C18 column; 35min gradient; MS1 (70,000 resolution), MS/MS (17,500) |

| Quality Control | Include pooled QC samples, solvent blanks, and internal standard mix throughout sequence | QC injection every 6-10 samples; monitor retention time stability and peak intensity |

This standardized approach has been demonstrated to effectively align small molecule data across different laboratories regardless of food type, establishing a foundational framework for generating high-quality, reproducible non-targeted metabolomics data [2]. The method incorporates a rationally-designed internal retention time standard (IRTS) mixture to correct for retention time shifts across different instruments and laboratories, significantly improving feature alignment and compound identification accuracy [2].

Data Processing and Molecular Networking

Following data acquisition, raw mass spectrometry files undergo preprocessing using specialized software such as XCMS, MZmine, or MS-DIAL for peak detection, retention time alignment, and feature quantification [3] [1]. The resulting feature tables are then subjected to feature-based molecular networking (FBMN) using the Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) platform, which groups MS/MS spectra based on similarity to visualize the chemical relationships within samples [3].

The molecular networking approach enables the organization of complex metabolomic data into molecular families, facilitating the annotation of both known and novel compounds [3]. In plant metabolomics studies, this technique has successfully characterized diverse biochemical classes, with research on Rumex sanguineus demonstrating that approximately 60% of detected metabolites belonged to polyphenol and anthraquinone classes, while also enabling the quantification of potentially toxic compounds like emodin across different plant tissues [3].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of non-targeted metabolomics requires careful selection of research reagents and materials to ensure comprehensive metabolite coverage and analytical reproducibility.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Non-Targeted Metabolomics

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Specifications/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | Mobile phase preparation; sample extraction and reconstitution | Methanol, acetonitrile, water, isopropanol; with 0.1% formic acid or ammonium formate |

| Internal Standards | Quality control; retention time alignment; quantification | Internal Retention Time Standard (IRTS) mixture; stable isotope-labeled compounds |

| Solid Phase Extraction Cartridges | Sample clean-up; metabolite fractionation | Reversed-phase C18; mixed-mode cation/anion exchange; according to target metabolome |

| Chromatography Columns | Metabolite separation prior to MS detection | Reversed-phase C18 (for non-polar); HILIC (for polar); 100×2.1mm, 1.7-1.8μm particles |

| Mass Spectrometry Calibration Solutions | Instrument calibration; mass accuracy maintenance | Sodium formate or proprietary calibration solutions specific to instrument manufacturer |

The selection of appropriate reagents is critical for method robustness, particularly when implementing cross-laboratory standardized protocols [2]. The use of high-purity solvents and well-characterized internal standards significantly reduces technical variation and enhances the detection of true biological differences in plant metabolomics studies.

Data Visualization and Interpretation

Effective data visualization is indispensable throughout the non-targeted metabolomics workflow, serving critical functions in data inspection, quality assessment, and insight communication [4]. Visualization strategies range from basic quality control plots to advanced molecular networks that enable chemical structural annotations and hypothesis generation.

The following diagram illustrates the process of molecular networking and metabolite annotation:

Diagram 2: Molecular networking for metabolite annotation.

Visualizations serve as a means to augment researchers' decision-making capabilities by summarizing data, extracting and highlighting patterns, and organizing relations within complex datasets [4]. In non-targeted metabolomics, effective visualizations include scatter plots with line graphs for data summary, cluster heatmaps for pattern extraction, and network visualizations for organizing and showcasing relationships between metabolites [4]. These visual tools are particularly valuable for communicating the complex results of plant metabolomics studies, where chemical diversity can be substantial and novel compounds are frequently encountered.

Applications in Plant Chemistry Research

Non-targeted metabolomics has demonstrated significant utility across diverse applications in plant chemistry research, particularly in the characterization of wild edible plants, investigation of plant-environment interactions, and discovery of bioactive compounds with pharmaceutical potential.

Research on Rumex sanguineus, a traditional medicinal plant from the Polygonaceae family, exemplifies the power of non-targeted metabolomics for comprehensive chemical characterization [3]. By applying UHPLC-HRMS analysis and feature-based molecular networking to different plant tissues (roots, stems, and leaves), researchers annotated 347 primary and specialized metabolites grouped into 8 biochemical classes, with the majority (60%) belonging to polyphenols and anthraquinones [3]. This approach also facilitated the quantification of emodin, a potentially toxic anthraquinone, revealing its higher accumulation in leaves compared to stems and roots—information critical for assessing safety in culinary and medicinal applications [3].

The non-targeted approach also enables the detection of unexpected compounds, including environmental contaminants such as pesticides and per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in food matrices, expanding its utility beyond endogenous metabolite profiling to comprehensive chemical safety assessment [2]. This capability is particularly valuable for evaluating wild edible plants where contamination profiles may be unknown.

The plant metabolome represents the final downstream product of cellular regulation and encompasses a staggering chemical diversity that is central to a plant's existence, defense, and interactions with the environment. This complex universe of metabolites is broadly categorized into primary metabolites and specialized metabolites. Primary metabolites include compounds such as carbohydrates, lipids, and amino acids, which are universally essential for fundamental processes like growth, development, reproduction, and energy storage [5] [6]. In contrast, specialized metabolites (historically termed secondary metabolites) are a vast array of compounds—including terpenoids, phenylpropanoids, polyketides, and alkaloids—that are not directly involved in primary growth processes but are crucial for the plant's survival and perpetuation [5] [6]. These specialized metabolites facilitate communication and interactions with other organisms and serve as an alternative defense mechanism, with over 200,000 distinct types identified across the plant kingdom [6].

The biosynthetic pathways for these compounds are sophisticated and energetically expensive. While the building blocks for specialized metabolites originate from highly conserved central metabolic pathways (e.g., glycolysis, shikimate, mevalonate), the later stages of biosynthesis are notably complex and diverse [6]. This diversity is influenced by factors such as cell type, developmental stage, and environmental cues, leading to the immense structural variety observed in plant specialized metabolites [6]. This chemical complexity, while a rich source of bioactive compounds for medicine and agriculture, also presents a significant analytical challenge, which non-targeted metabolomics is uniquely positioned to address.

Analytical Platforms for Non-Targeted Metabolomics

Non-targeted metabolomics aims to provide a comprehensive, unbiased analysis of all measurable metabolites in a biological sample. The two foremost analytical techniques employed in this field are Mass Spectrometry (MS) and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, each with distinct advantages and limitations, as detailed in the table below [5].

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Analytical Platforms in Plant Metabolomics

| Feature | Mass Spectrometry (MS) | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | High (Low LOD/LOQ) | Low to Moderate (µM range) |

| Metabolite Coverage | Hundreds per sample | Dozens per sample |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal; may require derivatization | Minimal |

| Analysis Nature | Destructive | Non-destructive |

| Quantification | Often requires internal standards | Directly quantitative |

| Structural Elucidation | Putative; requires fragmentation/chromatography | Direct; definitive for novel compounds |

| Key Strength | Broad metabolite coverage, high sensitivity | Structural identification, isomer differentiation, isotope tracing |

| Common Hyphenation | LC-MS, GC-MS | Not applicable |

MS is typically hyphenated with separation techniques like liquid or gas chromatography (LC-MS or GC-MS) to enhance metabolite coverage and identification [7] [5]. Its primary strength lies in its high sensitivity, enabling the detection of a vast range of metabolites. However, identification is often only putative and can lead to misidentifications [5]. Conversely, NMR spectroscopy is a nondestructive technique that allows for the simultaneous identification and quantification of metabolites without the need for extensive separation or reference standards [5]. Its powerful capability for de novo structural elucidation and isomer differentiation makes it particularly valuable for investigating plants where new or rare metabolites are present, though its lower sensitivity means it detects fewer metabolites per sample compared to MS [5]. Given their complementary capabilities, these techniques are often used in combination to provide a more holistic view of the plant metabolome [5].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

The following sections provide detailed, practical protocols for conducting a non-targeted metabolomics study in plants, incorporating both MS and NMR methodologies.

Protocol 1: Non-Targeted Metabolomics via LC-MS for Stress Response Investigation

This protocol is adapted from studies investigating the effects of abiotic stress and herbicide exposure on plant metabolism [7] [8]. It outlines the procedure from sample collection to data acquisition using Liquid Chromatography coupled to a high-resolution Mass Spectrometer.

1. Sample Collection and Preparation:

- Plant Material & Treatment: Grow plants under controlled conditions. Apply the stressor (e.g., drought simulated by PEG-6000, or chemical stressor like atrazine) to the treatment group while maintaining a control group [8]. The flowering period is often the most sensitive stage for stress studies [8].

- Harvesting: Collect leaf or other tissue samples at multiple time points post-treatment (e.g., day 0, 3, 6, 9). Immediately freeze the samples in liquid nitrogen to halt metabolic activity [8].

- Lyophilization and Homogenization: Lyophilize the frozen samples for 72 hours. Grind the lyophilized material into a fine powder using a homogenizer like a TissueLyser [8].

- Metabolite Extraction: Weigh ~50 mg of the lyophilized powder. Add 1000 µL of a cold extraction solvent (e.g., methanol:acetonitrile:water in a 2:2:1 ratio, containing internal standards). Vortex vigorously and homogenize with ceramic beads [8]. Centrifuge (e.g., 13,000 g for 15 min at 4°C) and collect the supernatant for analysis [7] [8].

2. LC-MS Data Acquisition:

- Chromatography: Use a UHPLC or UPLC system with a C18 reversed-phase column. A common mobile phase consists of (A) water with 0.1% formic acid and (B) acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid. Employ a gradient elution, for example: 0-2 min, 5% B; 2-15 min, 5-95% B; 15-17 min, 95% B; 17-17.1 min, 95-5% B; 17.1-20 min, 5% B [7].

- Mass Spectrometry: Analyze the samples using a high-resolution mass spectrometer, such as a Q-TOF or ion trap-triple quadrupole system. Acquire data in both positive and negative electrospray ionization (ESI) modes to maximize metabolite coverage. Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) is often used, where the top N most intense ions from a full MS scan are selected for MS/MS fragmentation [7].

3. Data Processing and Analysis:

- Peak Picking and Alignment: Process the raw data using software (e.g., MS-DIAL, XCMS) to detect features (ions characterized by m/z and retention time), align them across samples, and perform peak table construction.

- Metabolite Annotation: Annotate features by comparing their accurate mass and MS/MS fragmentation spectra against public databases such as MassBank, Metlin, and GNPS [3] [8]. Feature-Based Molecular Networking on the GNPS platform is a powerful tool for organizing metabolites based on spectral similarity and annotating within molecular families [3].

- Statistical Analysis: Import the peak table with normalized intensities into statistical software. Use multivariate statistics like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) to identify metabolites that discriminate between treatment and control groups. Univariate statistics (e.g., t-tests, ANOVA) with correction for multiple testing (e.g., False Discovery Rate) are also applied.

Figure 1: LC-MS non-targeted metabolomics workflow for plant stress studies.

Protocol 2: NMR-Based Metabolomics for Comprehensive Metabolite Profiling

This protocol is based on established NMR methodologies for plant metabolomics, which are particularly valuable for definitive structural identification and studies where sample preservation is desired [5].

1. Sample Preparation for NMR:

- Extraction: Prepare a polar extract from plant tissue (e.g., 100 mg fresh weight) using a deuterated solvent mixture like CD₃OD:KH₂PO₄ buffer in D₂O (1:1). The use of D₂O provides a field-frequency lock for the NMR spectrometer [5].

- Internal Standard: Include an internal chemical shift standard, such as 0.1 mM TSP (trimethylsilylpropanoic acid) or DSS, which also serves as a reference for quantification [5].

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the extract (e.g., 13,000 g for 10 min) to remove any particulate matter.

- Loading: Transfer a precise volume (e.g., 600 µL) of the clear supernatant into a standard 5 mm NMR tube.

2. NMR Data Acquisition:

- Instrument Setup: Conduct experiments on a high-field NMR spectrometer (e.g., 500 MHz or 600 MHz). Maintain a constant temperature (e.g., 298 K) during analysis.

- Key Pulse Sequences:

- 1D ¹H NMR: Begin with a standard one-dimensional pulse sequence with water suppression (e.g., presat or NOESY-presat). This is the primary experiment for profiling and quantification. Typical parameters: 64-128 transients, spectral width of 12-16 ppm, and a relaxation delay of 2-4 seconds [5].

- 2D NMR: For structural elucidation of unknown metabolites, acquire two-dimensional experiments. Essential 2D experiments include:

- ¹H-¹H COSY (Correlation Spectroscopy): Identifies scalar-coupled protons.

- ¹H-¹H TOCSY (Total Correlation Spectroscopy): Reveals correlations within a spin system.

- ¹H-¹³C HSQC (Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence): Identifies direct ¹H-¹³C couplings, providing a map of protonated carbons.

- ¹H-¹³C HMBC (Heteronuclear Multiple Bond Correlation): Detects long-range ¹H-¹³C couplings, crucial for establishing connectivity between quaternary carbons and protons [5].

3. NMR Data Processing and Analysis:

- Processing: Apply Fourier transformation to the Free Induction Decay (FID). Use phase correction and baseline correction. Reference the spectrum to the internal standard (e.g., TSP at 0.0 ppm).

- Spectral Bucketing: To facilitate statistical analysis, segment the ¹H NMR spectrum into small regions (buckets or bins) and integrate the area under each segment. This reduces the complexity of the data.

- Metabolite Identification and Quantification: Identify metabolites by comparing the chemical shifts, coupling constants, and spin-spin correlations from 1D and 2D spectra with reference spectra in databases (e.g., HMDB, BMRB, in-house libraries). The concentration of metabolites can be directly calculated by integrating their resolved peaks relative to the internal standard [5].

- Chemometric Analysis: Subject the bucketed data or quantified concentrations to multivariate statistical analysis (PCA, PLS-DA) to identify metabolic patterns and biomarkers.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful non-targeted metabolomics relies on a suite of essential reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions and their specific functions in a typical workflow.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Plant Non-Targeted Metabolomics

| Reagent/Material | Function & Application in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Methanol, Acetonitrile, Water (LC-MS Grade) | Used as extraction solvents and LC-MS mobile phases. High purity is critical to minimize background noise and ion suppression in MS [7] [8]. |

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., CD₃OD, D₂O) | NMR solvent that provides a field-frequency lock and enables the accurate shimming of the magnetic field [5]. |

| Internal Standards (e.g., TSP, DSS) | Added to NMR samples for chemical shift referencing (calibration) and as a known concentration for quantitative analysis [5]. |

| Formic Acid (LC-MS Grade) | A mobile phase additive in LC-MS (0.1%) to improve chromatographic peak shape and enhance ionization efficiency in positive ESI mode [7]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG-6000) | Used to simulate osmotic (drought) stress in plant growth experiments by creating a negative water potential in the growth medium [8]. |

| Chemical Shift Reference Databases (e.g., HMDB, BMRB) | Electronic libraries of known metabolite NMR spectra used for the definitive identification of compounds in complex plant extracts [5]. |

| MS/MS Spectral Libraries (e.g., GNPS, MassBank) | Public repositories of mass spectral fragmentation data used for the annotation of metabolites in LC-MS/MS studies [3] [8]. |

Integration with Other Omics and Visualization of Metabolic Pathways

Non-targeted metabolomics is most powerful when integrated with other omics technologies in a multi-omics approach. The combination of metabolomics with transcriptomics is particularly effective for identifying genes involved in specialized metabolic pathways [9] [6]. This integration operates on the hypothesis that the expression of genes encoding enzymes in a biosynthetic pathway will be co-regulated and will correlate with the accumulation of the pathway's end product [9]. For instance, this approach has been successfully used to discover pathways for compounds like kavalactones in kava and podophyllotoxin in mayapple [9].

Specialized metabolite biosynthesis begins with primary metabolic pathways, which provide the essential precursors. The diagram below illustrates the major branching points from primary to specialized metabolism.

Figure 2: Biosynthetic origins of major specialized metabolite classes from primary metabolism.

This multi-omics framework, supported by the detailed protocols for MS and NMR, provides researchers with a comprehensive strategy to move from simply observing metabolic changes to understanding their genetic and enzymatic basis, ultimately enabling the engineering of pathways for sustainable production of valuable plant metabolites [9] [6].

Non-targeted metabolomics has emerged as a powerful analytical strategy in plant chemistry research, enabling the comprehensive investigation of low-molecular-weight metabolites without prior hypothesis. This approach captures the metabolic phenotype of plants, reflecting interactions between genetics, development, and environmental influences [5]. The field primarily distinguishes between metabolic fingerprinting, which provides a rapid, high-throughput overview of sample classification, and comprehensive profiling, which aims to identify and quantify a broader range of metabolites for detailed biochemical interpretation [10] [11].

In plant sciences, these techniques are particularly valuable because plants produce a vast array of specialized metabolites—estimated at over a million across the plant kingdom—that play crucial roles in survival, defense, and communication [11]. These compounds also have significant applications in drug development, agriculture, and food science. However, the tremendous structural diversity of plant metabolites presents substantial analytical challenges, with current technologies able to identify only a fraction of the metabolites detected in typical plant extracts [11].

This application note outlines the core principles, methodologies, and practical applications of non-targeted metabolomics in plant research, providing detailed protocols for researchers and scientists seeking to implement these approaches in their workflows.

Key Concepts and Analytical Approaches

Defining Metabolic Fingerprinting and Profiling

Metabolic fingerprinting is a non-targeted approach focused on rapid sample classification and pattern recognition without necessarily identifying all metabolites. It generates global spectral signatures that can be used to discriminate between sample groups based on their biological origin or treatment condition [5]. This approach is particularly useful for quality control, phenotyping, and detecting metabolic responses to environmental stressors or genetic modifications.

Comprehensive metabolic profiling extends beyond fingerprinting by aiming to identify and quantify a wide range of metabolites, providing deeper biochemical insights. While still non-targeted in nature, profiling seeks to put names to the discriminating features, enabling biological interpretation at the pathway level [7] [12]. This approach is more resource-intensive but offers greater mechanistic understanding of plant metabolic processes.

Analytical Techniques in Non-Targeted Metabolomics

Two principal analytical platforms dominate non-targeted metabolomics, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

Table 1: Comparison of Major Analytical Platforms in Plant Metabolomics

| Platform | Sensitivity | Metabolite Coverage | Key Strengths | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mass Spectrometry (MS) | High (low LOD/LOQ) | Hundreds to thousands of features | High sensitivity, broad dynamic range, structural information via MS/MS | Destructive analysis, typically requires chromatography, putative identification only |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Moderate (µM-mM range) | Dozens to hundreds of metabolites | Non-destructive, quantitative, structural elucidation power, high reproducibility | Lower sensitivity, spectral overlap challenges |

Mass Spectrometry platforms, particularly when coupled with separation techniques like liquid chromatography (LC-MS) or gas chromatography (GC-MS), offer high sensitivity and can detect thousands of metabolite features in a single sample [7] [11]. LC-MS is preferred for thermally labile compounds such as alkaloids, phenolic compounds, and most secondary metabolites, while GC-MS is suitable for volatile compounds and those made amenable to analysis through derivatization (e.g., organic acids, sugars) [10]. The workflow typically involves sample extraction, chromatographic separation, ionization (commonly electrospray ionization), and mass analysis using high-resolution instruments such as time-of-flight (TOF) or Orbitrap mass analyzers [12].

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance spectroscopy provides a complementary approach, with the key advantage of being non-destructive and inherently quantitative without requiring reference standards [5]. Although less sensitive than MS, NMR excels at structural elucidation of unknown compounds and isomer differentiation, making it particularly valuable for investigating novel plant metabolites [5]. Proton (¹H) NMR is most commonly used due to the high natural abundance of hydrogen and relatively short experiment times.

Diagram: Decision Workflow for Selecting Analytical Platforms in Plant Metabolomics

Experimental Design and Workflow

Sample Preparation and Extraction

Proper sample preparation is critical for generating reliable and reproducible metabolomic data. The general workflow begins with immediate quenching of metabolism, typically using liquid nitrogen, to preserve the metabolic state at the time of collection [5]. For plant tissues, this is followed by homogenization (often with liquid nitrogen), and then metabolite extraction.

A common effective extraction protocol for comprehensive plant metabolomics involves:

- Tissue Processing: Grind 30-50 mg of lyophilized leaf material under liquid nitrogen to a fine powder [12].

- Biphasic Extraction: Use a methyl-tert-butyl-ether:methanol (MTBE:MeOH, 3:1 v:v) solvent system to extract both polar and non-polar metabolites simultaneously [12].

- Internal Standards: Add stable isotope-labeled internal standards (e.g., U-¹³C-sorbitol, L-Alanine-d4) for quality control and potential normalization [12].

- Extraction Procedure: Vortex, incubate on an orbital shaker (40 rpm, 45 min, 4°C), sonicate in a water bath (15 min, 4°C), and centrifuge (10,000×g, 10 min, 4°C) [12].

- Sample Preparation for Analysis: Transfer aliquots of the soluble fraction to new vials and dry under a stream of nitrogen or in a speed vacuum concentrator.

For NMR-based approaches, samples are typically reconstituted in deuterated solvents (e.g., D₂O, CD₃OD) containing a reference standard such as trimethylsilylpropanoic acid (TSP) for chemical shift calibration [5].

Data Acquisition and Metabolite Identification

The data acquisition strategy depends on the analytical platform selected. For LC-MS-based non-targeted metabolomics, reverse-phase chromatography with C18 columns is commonly used, with gradients typically employing water and acetonitrile or methanol, both modified with 0.1% formic acid to enhance ionization [7]. Data-dependent acquisition (DDA) is frequently employed, where the top N most intense ions from the full MS scan are selected for MS/MS fragmentation to generate structural information.

For GC-MS analyses, samples typically require derivatization to increase volatility and stability. A common approach follows the protocol of Erban et al. (2007), using methoxyamine hydrochloride in pyridine followed by N-trimethylsilyl-N-methyl trifluoroacetamide (MSTFA) [12]. Separation is achieved using DB-35MS or similar columns with temperature ramping from 85°C to 360°C.

Metabolite identification remains a significant challenge in non-targeted plant metabolomics, with typically only 2-15% of detected peaks confidently annotated through spectral library matching [11]. The Metabolomics Standards Initiative (MSI) has established confidence levels for metabolite identification:

Table 2: Metabolite Identification Confidence Levels

| Confidence Level | Identification Evidence | Typical Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Level 1: Identified | Matching to authentic standard using two orthogonal properties (e.g., RT + MS/MS) | Commercial standards, in-house libraries |

| Level 2: Putatively Annotated | Spectral similarity to reference library without RT match | GNPS, MassBank, METLIN, RefMetaPlant |

| Level 3: Putative Class | Characteristic chemical class features | CANOPUS, NPClassifier, rule-based fragmentation |

| Level 4: Unknown | Distinguished only by m/z and RT | De novo characterization needed |

Several databases and software tools have been developed to facilitate metabolite annotation in plants:

- RefMetaPlant: A reference metabolome database specifically for plants [11]

- Plant Metabolome Hub (PMhub): Consolidates MS/MS data for nearly 189,000 plant metabolites [11]

- GOLM Metabolome Database: Particularly useful for GC-MS based metabolomics [12]

- KEGG and HMDB: Provide pathway information and metabolite annotations [12]

- GNPS (Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking): Enables community-wide sharing of MS/MS spectra [11]

Advanced computational approaches, including machine learning tools like CSI-FingerID, CANOPUS, and Mass2SMILES, are increasingly being employed to improve annotation rates and predict compound classes from MS/MS data without authentic standards [11].

Applications in Plant Chemistry Research

Investigating Environmental Stress Responses

Non-targeted metabolomics has proven valuable for understanding how plants respond to abiotic and biotic stressors. A recent study investigated the hidden effects of the herbicide atrazine and its degradation products on Japanese radish (Raphanus sativus var. longipinnatus) metabolism [7]. Using LC-MS-based non-targeted metabolomics, researchers discovered that both atrazine and its metabolites (DEA, DIA, DEDIA) significantly altered amino acid profiles in the plants, despite the absence of visible stress symptoms. This demonstrates the sensitivity of metabolomics in detecting subtle biochemical changes before morphological symptoms appear.

The study employed chemometric tools for data analysis, including partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA), to identify metabolic patterns distinguishing treatment groups. Key findings included disruptions in branched-chain amino acid metabolism, highlighting the potential impact of environmental contaminants on plant nutritional quality [7].

Cultivar Differentiation and Precision Breeding

Non-targeted metabolomics enables the identification of metabolic fingerprints that distinguish plant cultivars with different genetic backgrounds. Research on five Coffea arabica cultivars grown in field conditions demonstrated distinct metabolic signatures among cultivars, with 41 metabolites identified as key discriminators [12]. The non-targeted GC-MS approach detected 463 metabolic features, with major classes including sugars, amino acids, lipids, phenylpropanoids, and phenolic compounds.

PLS-DA analysis revealed that ferulic acid, theobromine, octopamine, rosmarinic acid, and gibberellin were particularly important for cultivar discrimination [12]. This metabolic fingerprinting approach provides valuable tools for coffee breeding programs, allowing selection of cultivars with desirable traits such as stress resistance or cup quality based on their metabolic profiles.

Diagram: Integrated Workflow for Non-Targeted Plant Metabolomics

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of non-targeted metabolomics requires careful selection of reagents and materials. The following table outlines key solutions for plant metabolomics research:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Plant Metabolomics

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| MTBE:MeOH (3:1, v:v) | Biphasic extraction solvent | Simultaneously extracts polar and non-polar metabolites; enables comprehensive metabolite coverage [12] |

| Deuterated Solvents (D₂O, CD₃OD) | NMR sample preparation | Provides locking signal for NMR stability; enables quantitative analysis without internal standards [5] |

| Methoxyamine hydrochloride | GC-MS derivatization agent | Protects carbonyl groups and reduces tautomerization; improves metabolite stability and separation [12] |

| MSTFA | GC-MS silylation reagent | Increases volatility of metabolites; essential for GC-MS analysis of non-volatile compounds [12] |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Standards | Quality control and normalization | Corrects for instrument variation; validates analytical performance [12] |

| C18 LC Columns | Reverse-phase chromatography | Separates metabolites by hydrophobicity; workhorse for LC-MS metabolomics [7] |

| DB-35MS GC Columns | GC-MS separation | Mid-polarity stationary phase; suitable for diverse metabolite classes [12] |

Data Analysis and Interpretation Strategies

Statistical and Bioinformatics Approaches

The analysis of non-targeted metabolomics data requires specialized statistical approaches to extract meaningful biological information from complex multivariate datasets. Common strategies include:

- Unsupervised methods such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for exploratory data analysis and outlier detection [7] [12]

- Supervised methods including Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) and Orthogonal PLS-DA (OPLS-DA) for identifying metabolites that discriminate between predefined sample groups [7] [12]

- Molecular networking based on MS/MS similarity to visualize chemical relationships and identify structurally related metabolites without requiring prior identification [11]

- Information theory-based metrics to assess metabolic diversity and complexity without complete metabolite identification [11]

For studies where metabolite identification remains challenging, several identification-free approaches have been developed. These include analyzing spectral features directly, comparing fold-changes of unknown features, and employing database-independent visualization tools that cluster metabolites based on fragmentation patterns or chromatographic behavior [11].

Data Visualization and Reporting

Effective visualization of metabolomics data is essential for interpretation and communication of results. The complexity of metabolomic datasets often requires multiple visualization strategies:

- Volcano plots to display both statistical significance (p-values) and magnitude of change (fold-change) simultaneously

- Heatmaps with hierarchical clustering to visualize patterns in metabolite abundance across sample groups

- Pathway maps to display metabolic perturbations in the context of biochemical networks

- Box and whisker plots for comparing distributions of individual metabolites across experimental groups [13]

When preparing metabolomics data for publication, it is essential to follow journal guidelines regarding data presentation. Key considerations include providing clear, self-explanatory titles for all tables and figures, defining all abbreviations in footnotes, and ensuring consistency in formatting across all visual elements [13]. Most journals now require raw metabolomics data to be deposited in public repositories such as MetaboLights or the Metabolomics Workbench.

Non-targeted metabolomics provides powerful approaches for investigating plant chemistry, from initial metabolic fingerprinting for sample classification to comprehensive profiling for detailed biochemical interpretation. The integration of advanced analytical platforms, particularly high-resolution mass spectrometry and NMR spectroscopy, with sophisticated bioinformatics tools has dramatically enhanced our ability to characterize the complex metabolomes of plants.

Despite significant advances, challenges remain in metabolite identification, data integration, and biological interpretation. Ongoing developments in computational approaches, including machine learning and artificial intelligence, are promising strategies to address these limitations. As the field continues to evolve, non-targeted metabolomics will play an increasingly important role in plant research, from fundamental studies of metabolic diversity to applied applications in crop improvement, natural product discovery, and environmental monitoring.

For researchers implementing these approaches, careful attention to experimental design, sample preparation, quality control, and data analysis is essential for generating robust and biologically meaningful results. The protocols and applications outlined in this article provide a foundation for developing effective metabolomics strategies in plant chemistry research.

In the field of plant chemistry research, a significant challenge persists: the vast majority of metabolites detected through modern analytical techniques remain unidentified. This unexplored chemical space, often termed "metabolic dark matter," represents a critical knowledge gap in understanding plant physiology, stress responses, and biosynthetic potential [11]. Current untargeted liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analyses typically detect thousands of metabolic features from plant extracts, yet studies consistently report that >85% of these peaks cannot be annotated with confidence using standard approaches [11]. This identification bottleneck limits our ability to fully decipher the chemical diversity that plants employ for defense, communication, and adaptation.

The plant metabolome is estimated to contain over a million metabolites, yet comprehensive databases contain only a fraction of these compounds. For instance, the KNApSAcK plant metabolite database lists approximately 63,723 compounds as of its 2024 update, highlighting the immense disparity between known and unknown chemical space in plants [11]. This review outlines integrated experimental and computational strategies to illuminate this dark matter, with particular emphasis on approaches relevant to plant specialized metabolism, natural product discovery, and crop improvement research.

Experimental Workflows for Functional Group Characterization

Multiplexed Chemical Labeling (MCheM)

Principle: MCheM introduces chemical reactivity as an additional dimension to LC-MS/MS analyses by using selective derivatization reagents that target specific functional groups, thereby revealing structural information through predictable mass shifts [14].

Protocol:

- Post-column Derivatization Setup: Integrate a microfluidic reactor after the analytical column but prior to MS ionization.

- Reagent Selection: Employ multiple, parallel derivatization reagents targeting complementary functional groups (e.g., hydroxyls, amines, carboxylic acids).

- Reaction Optimization: Adjust flow rates, reaction temperature, and solvent compatibility to maintain chromatographic integrity while ensuring complete derivatization.

- Data Acquisition: Acquire MS/MS data in real-time during reagent introduction.

- Data Analysis: Identify mass shifts corresponding to specific functional group additions across different reagent channels.

Applications in Plant Research: This approach proved particularly valuable for characterizing unknown compounds in complex plant extracts, where it helped identify a Michael system in previously unannotated metabolites, dramatically narrowing plausible substructures [14].

Feature-Based Molecular Networking (FBMN)

Principle: FBMN groups metabolites based on similarity of their MS/MS fragmentation patterns, creating visual networks where structurally related compounds cluster together [15] [3].

Protocol:

- LC-MS/MS Data Acquisition: Perform untargeted LC-MS/MS analysis using data-dependent acquisition (DDA) or data-independent acquisition (DIA).

- Feature Detection: Process raw data using tools like MZmine or OpenMS to extract chromatographic features, alignment, and MS/MS spectral decomposition.

- Spectral Networking: Upload processed data to GNPS platform to construct molecular networks based on MS/MS similarity.

- Statistical Analysis: Apply multivariate statistics to identify significant features across experimental conditions using provided R or Python scripts [15].

- Annotation Propagation: Leverage network neighborhoods to propagate annotations from known to unknown metabolites.

Implementation Example: In a study of Rumex sanguineus, FBMN enabled the comprehensive annotation of 347 primary and specialized metabolites, with 60% belonging to polyphenols and anthraquinones classes, demonstrating the power of this approach for characterizing chemically complex plant extracts [3].

Table 1: Comparison of Experimental Approaches for Metabolite Annotation

| Method | Key Principle | Structural Information Gained | Limitations | Suitable for Plant Sample Types |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCheM [14] | Selective post-column derivatization | Functional group presence (hydroxyls, amines, carboxylic acids) | Requires optimization of reaction conditions; commercially available reagents | Complex plant extracts; natural product mixtures |

| FBMN [15] [3] | MS/MS spectral similarity networking | Structural similarity; compound classes | Limited for novel scaffolds without reference spectra | Wild edible plants; medicinal plants; stress-responsive tissues |

| KGMN [16] | Multi-layer network integration | Biochemical relationships; putative identities | Depends on quality of initial seed annotations | Plant tissues with well-annotated core metabolomes |

Computational Frameworks for Systematic Annotation

Knowledge-Guided Multi-Layer Network (KGMN)

Principle: KGMN integrates three complementary networks to enable annotation propagation from knowns to unknowns [16]:

- Knowledge-based Metabolic Reaction Network (KMRN): Biochemical transformations from databases (KEGG) expanded with in silico enzymatic reactions

- Knowledge-guided MS/MS Similarity Network: Structural relationships constrained by biochemical plausibility

- Global Peak Correlation Network: Different ion forms (adducts, fragments) of the same metabolite

Workflow Implementation:

- Seed Annotation: Confidently identify a subset of metabolites using standard MS/MS library matching

- Network Expansion: Recursively propagate annotations to reaction-paired neighbors using mass differences, retention time predictions, and MS/MS similarity

- Unknown Metabolite Prediction: Generate putative structures for unannotated features using in silico enzymatic transformations from known seed metabolites

- Validation: Corroborate predictions using in silico MS/MS tools and repository mining

Plant Research Applications: KGMN has demonstrated capability to annotate ~100-300 putative unknowns in individual datasets, with >80% corroboration rate by in silico MS/MS tools, making it particularly valuable for exploring plant specialized metabolism [16].

ATLASx for Biochemical Space Expansion

Principle: ATLASx predicts hypothetical biochemical transformations using 489 generalized enzymatic reaction rules applied to a unified database of 1.5 million biological compounds [17].

Protocol for Plant Natural Product Discovery:

- Query Compound Input: Input a plant natural product of interest or use the database exploration tools

- Pathway Prediction: Identify potential biosynthetic pathways or transformation products

- Reaction Rule Application: Apply expert-curated reaction rules from BNICE.ch to predict novel derivatives

- Structural Evaluation: Assess predicted compounds for novelty and biological relevance

- Experimental Prioritization: Select high-priority targets for isolation or synthesis based on predicted properties

This approach has been successfully used to predict over 5 million reactions and integrate nearly 2 million compounds into biochemical space, significantly expanding the framework for identifying plant natural products [17].

Integrated Multi-Omics Approaches for Plant Metabolism

The integration of metabolomics with genomics and transcriptomics provides a powerful strategy for linking metabolites to their biosynthetic origins. This is particularly relevant for plant natural products, where many biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) remain uncharacterized [18].

Protocol for Integrated Omics in Plant Research:

- Genome Sequencing and Assembly: Use long-read technologies (PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) to obtain contiguous assemblies capable of capturing complete BGCs

- BGC Identification: Annotate BGCs using antiSMASH with plant-specific rules [18]

- Metabolite Profiling: Perform untargeted LC-MS/MS under various growth conditions and tissues

- Correlation Analysis: Integrate gene expression and metabolite abundance data to identify candidate genes for specific metabolites

- Functional Validation: Use heterologous expression or gene silencing to verify gene-metabolite relationships

This integrated approach has accelerated the discovery of novel plant natural products by providing a direct link between genetic capacity and metabolic output [18].

Table 2: Computational Tools for Metabolite Annotation in Plant Research

| Tool/Platform | Primary Function | Data Input Requirements | Strengths for Plant Metabolomics | Integration Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GNPS/FBMN [15] | Molecular networking & annotation propagation | LC-MS/MS raw data or feature tables | Extensive plant-relevant spectral libraries; user-friendly web interface | Cytoscape visualization; statistical analysis tools |

| SIRIUS/CANOPUS [11] | In silico fragmentation & compound class prediction | MS/MS spectra | Predicts structural classes using NPClassifier ontology; requires no reference spectra | Standalone tool; can process output from various pre-processing pipelines |

| KGMN [16] | Multi-layer network annotation | LC-MS/MS data with minimal seed annotations | Excellent for annotating unknown plant metabolites using biochemical context | Compatible with MS data pre-processed by common tools |

| ATLASx [17] | Biochemical reaction prediction | Compound structures or queries | Expands known biochemical space; predicts novel transformations | Web interface; connects with biochemical databases |

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Plant Metabolite Discovery

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Example in Plant Research | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Derivatization Reagents (e.g., hydroxyl-, amine-targeting) [14] | Reveal specific functional groups through predictable mass shifts | Characterizing reactive groups in unknown plant specialized metabolites | Commercial availability; compatibility with LC mobile phases |

| Authentic Standards | Confident metabolite identification (MSI Level 1) | Quantification of emodin in Rumex sanguineus tissues [3] | Cost; availability of rare plant compounds |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Precursors (e.g., ^13C, ^15N) | Tracing metabolic pathways and confirming formula assignments | Elucidating biosynthetic pathways of plant natural products | Incorporation efficiency; cost for multiple labeling |

| Specialized LC Columns (HILIC, reversed-phase) | Separation of diverse metabolite classes | Comprehensive coverage of polar and non-polar plant metabolites | Method development time; column longevity with crude extracts |

| Enzyme Inhibitors/Activators | Probing metabolic pathways in vivo | Investigating flux through competing biosynthetic routes | Specificity; potential pleiotropic effects |

Visualizing the Integrated Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental and computational pipeline for advancing from unknown metabolic features to annotated metabolites in plant research:

Diagram 1: Integrated metabolite discovery workflow for plant research.

The challenge of metabolic dark matter in plant chemistry research is being addressed through innovative experimental and computational strategies that create additional layers of information beyond traditional MS/MS matching. The integration of chemical derivatization, molecular networking, knowledge-guided algorithms, and multi-omics approaches provides a powerful framework for systematically annotating previously unknown metabolites. As these technologies continue to mature and become more accessible to the research community, we anticipate significant advances in our understanding of plant chemical diversity, biosynthetic pathways, and ecological functions. The protocols and resources outlined herein provide a roadmap for researchers seeking to illuminate the dark corners of plant metabolism and unlock the full potential of plant-derived compounds for pharmaceutical applications, crop improvement, and fundamental biological discovery.

Non-targeted metabolomics has emerged as a powerful analytical strategy for comprehensively characterizing the small molecule composition of biological systems without prior hypothesis. In the context of biodiversity screening and novel compound discovery, this approach enables researchers to capture the vast chemical diversity present in plants, marine organisms, and other biological resources, much of which remains unexplored [11]. The technological advancement of liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) platforms now allows researchers to detect thousands of metabolite features from single organ extracts, providing unprecedented access to nature's chemical treasury [11]. This capability is particularly valuable given that current plant metabolite databases document only a fraction of the estimated over one million metabolites existing in the plant kingdom [11]. The application of non-targeted metabolomics within biodiversity research thus addresses a critical bottleneck in natural product discovery, enabling the systematic mapping of chemical diversity across species and ecosystems while facilitating the identification of novel compounds with potential applications in pharmaceuticals, nutraceuticals, and agriculture.

Standardized Experimental Protocol for Cross-Laboratory Metabolomics

The reproducibility of non-targeted metabolomics data across different laboratories and instrumentation platforms remains a significant challenge in biodiversity research. To address this limitation, a standardized protocol has been developed specifically for cross-laboratory comparison of biological samples, focusing on solid phase extraction (SPE) reverse phase liquid chromatography (RPLC) positive mode electrospray (+ESI) high resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) analysis [2]. This protocol serves as a foundational framework for generating high-quality, reproducible nontargeted metabolomics data that enables alignment of small molecule data across different laboratories, regardless of biological source [2].

Sample Preparation and Processing

Consistent practices of sample collection, handling, storage, and transportation are maintained from the point of collection through preparation and processing. Biological materials are collected in a "ready-to-analyze" manner from their natural environment or cultivated sources. For field-collected specimens, a random selection of individuals is recommended to account for biological variation. Samples undergo pre-processing steps that include lyophilization followed by homogenization into a fine powder to normalize variation in water content and create a consistent analytical matrix [2].

The extraction process employs a standardized solid phase extraction protocol using 96-well SPE plates, which provides a balance between broad metabolome coverage and practical implementation across different mass spectrometry instrument platforms. This approach demonstrates robustness to matrix variation across diverse biological samples [2].

Data Acquisition Parameters

The analytical workflow employs reverse phase liquid chromatography separation coupled to high-resolution mass spectrometry detection. A key innovation in this standardized protocol is the implementation of a rationally-designed internal retention time standard (IRTS) mixture, which enables retention time alignment across different laboratories and instrumentation platforms [2]. This IRTS mixture is spiked into every sample prior to analysis, facilitating cross-laboratory data comparison.

Mass spectrometry analysis is performed in data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode, which collects both precursor (MS1) and fragmentation (MS/MS) spectra. The MS settings include:

- Resolution: 120,000 for MS1 and 30,000 for MS/MS

- Scan range: m/z 100-1500

- Collision energies: Stepped normalized collision energy (NCE) of 20, 40, and 60 eV

- Dynamic exclusion: 10 seconds after fragmentation [2]

Data Processing and Analysis

Raw data files are processed using feature detection software (e.g., Progenesis QI, XCMS, or MS-DIAL) with consistent parameter settings across all participating laboratories. The processing includes retention time alignment using the internal standard mixture, peak picking, deconvolution, and adduct identification [2].

Feature-based molecular networking through the Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) platform is employed for metabolite annotation and comparison across samples [3]. This computational approach groups related metabolite features based on similarity of their MS/MS fragmentation patterns, enabling the organization of complex metabolomic data into molecular families and facilitating the identification of novel compounds through structural relationships to known metabolites [3] [11].

Table 1: Key Steps in Standardized Non-Targeted Metabolomics Protocol

| Protocol Step | Key Parameters | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Lyophilization, homogenization, SPE extraction | Normalize matrix variation, broad metabolome coverage |

| Chromatography | Reverse phase LC, C18 column, 30°C column temperature | Separate complex metabolite mixtures |

| Mass Spectrometry | +ESI, 120,000 resolution MS1, DDA MS/MS | High-quality spectral data for compound identification |

| Quality Control | Internal RT standards, pooled QC samples | Monitor system performance, enable cross-lab alignment |

| Data Processing | Feature detection, RT alignment, molecular networking | Annotate metabolites, identify novel compounds |

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The successful implementation of non-targeted metabolomics for biodiversity screening requires specific research reagents and analytical tools that enable comprehensive metabolite profiling and accurate compound identification.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biodiversity Metabolomics

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Plates | Metabolite extraction and cleanup | 96-well format for high-throughput processing |

| Internal Retention Time Standards (IRTS) | Retention time alignment across platforms | Rationally-designed mixture spiked in all samples [2] |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | Mobile phase preparation | Methanol, acetonitrile, water with 0.1% formic acid |

| Analytical Standards | Metabolite identification and quantification | Pure compounds for confirmation (e.g., emodin) [3] |

| HILIC & RPLC Columns | Complementary separation mechanisms | RPLC for non-polar, HILIC for polar metabolites [2] |

| Mass Spectral Libraries | Metabolite annotation | GNPS, METLIN, MassBank, RefMetaPlant [11] |

| Bioassay Kits | Bioactivity screening | Anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, anticancer assays [19] |

The selection of appropriate reagents and materials must consider the specific biological matrix being analyzed. For plant materials rich in polyphenols and anthraquinones (such as Rumex sanguineus), specific analytical standards like emodin are essential for quantitative analysis and toxicity assessment [3]. The integration of bioassay screening materials enables simultaneous chemical characterization and biological activity assessment, creating a direct path from compound discovery to functional validation [19].

Data Analysis and Computational Workflows

The analysis of non-targeted metabolomics data generated from biodiversity screening involves multiple computational steps that transform raw spectral data into biologically meaningful information about novel compounds.

Molecular Networking and Metabolite Annotation

Feature-based molecular networking (FBMN) has become a cornerstone technique for organizing and annotating the complex metabolomic data generated from biological samples. This approach, implemented through platforms like GNPS, groups metabolite features based on the similarity of their MS/MS fragmentation patterns, creating visual networks where structurally related compounds cluster together [3]. This technique is particularly valuable for biodiversity screening as it enables the identification of novel compounds through their structural relationships to known metabolites, effectively mapping the chemical diversity within biological samples [3] [11].

Statistical analysis techniques including partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) and volcano plot analysis are employed to identify metabolites that differentiate sample groups, such as resistant versus susceptible plant accessions or infected versus control samples [20]. These approaches help prioritize novel compounds with potential biological significance for further investigation.

Compound Identification and Classification

Metabolite annotation in non-targeted metabolomics follows the confidence levels established by the Metabolomics Standards Initiative (MSI). Computational tools such as CSI-FingerID and CANOPUS enable the prediction of compound structures and classification into chemical classes based solely on MS/MS fragmentation data, significantly expanding annotation coverage beyond library-based approaches [11]. These tools are particularly valuable for novel compound discovery as they can propose structural classifications for previously uncharacterized metabolites.

For biodiversity applications, specialized compound class annotation tools can detect characteristic fragmentation patterns associated with specific metabolite families, such as flavonoids, resin glycosides, and acylsugars, enabling class-level annotation even when exact structures are unknown [11].

Diagram 1: Data analysis workflow for novel compound discovery.

Application Case Studies in Biodiversity Research

Chemical Characterization of Medicinal Plants

Non-targeted metabolomics has proven particularly valuable for the comprehensive chemical characterization of medicinal plants with historical traditional use. In a study of Rumex sanguineus, a traditional medicinal plant from the Polygonaceae family, non-targeted metabolomics based on UHPLC-HRMS and feature-based molecular networking enabled the annotation of 347 primary and specialized metabolites grouped into 8 biochemical classes [3]. The analysis revealed that most detected metabolites (60%) belonged to polyphenols and anthraquinones classes, providing a scientific basis for understanding both the potential beneficial and harmful compounds in this species [3]. Importantly, the quantification of emodin across different plant tissues (leaves, stems, and roots) demonstrated higher accumulation in leaves, highlighting the importance of thorough metabolomic studies for safety assessment of plants transitioning from traditional medicinal use to modern culinary applications [3].

Uncovering Biochemical Resistance Mechanisms in Wild Plant Species

The application of non-targeted metabolomics to study plant-insect interactions has revealed sophisticated chemical defense systems in wild plant species. Research on wild tomato accessions (Solanum cheesmaniae and Solanum galapagense) subjected to herbivory by whitefly (Bemisia tabaci) and tomato leafminer (Phthorimaea absoluta) employed LC-HRMS-based non-targeted metabolomics to identify resistance-related metabolites [20]. The study revealed distinct sets of resistance-related constitutive (RRC) and induced (RRI) metabolites, with key compounds involved in fatty acid and associated biosynthesis pathways, including triacontane, di-hexanoic acid, dodecanoic acid, and 12-hydroxyjasternic acid [20].

Volcano plot analysis demonstrated a higher number of significantly upregulated metabolites in wild accessions following herbivory, indicating precise metabolic reprogramming in response to insect attack [20]. This application exemplifies how non-targeted metabolomics can uncover biochemical mechanisms governing economically valuable traits in wild species, providing both candidate metabolites for breeding programs and potential novel compounds for agrochemical development.

Table 3: Quantitative Metabolite Findings from Biodiversity Case Studies

| Study | Biological System | Total Metabolites Detected | Key Compound Classes Identified | Significant Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rumex sanguineus Analysis [3] | Medicinal plant (Polygonaceae) | 347 metabolites | Polyphenols (60%), Anthraquinones | Emodin accumulation highest in leaves |

| Wild Tomato Insect Resistance [20] | Solanum accessions under herbivory | 7,884 consistent peaks at 6 hpi | Fatty acids, Galactolipids, Sphinganine | 503 induced metabolites post-herbivory |

| Convolvulaceae Resin Glycosides [11] | 30 Convolvulaceae species | Thousands of features | Resin glycosides | Expanded known resin glycosides from 300 to thousands |

Integration with Biodiversity Conservation and Bioprospecting

The application of non-targeted metabolomics in biodiversity screening aligns with growing efforts in biodiversity conservation and sustainable bioprospecting. Modern approaches emphasize sustainable sourcing methods to avoid environmental concerns, including the use of in vitro cultivation and biotechnological production to reduce pressure on wild resources [21]. The Marbio platform in Norway exemplifies this integrated approach, combining marine biology, chemistry, and biomedical applications while adhering to ethical collection practices that avoid overharvesting and focus on Red List species protection [19].

The development of comprehensive reference databases and digital resources represents another critical integration point for non-targeted metabolomics in biodiversity research. Initiatives such as the Reference Metabolome Database for Plants (RefMetaPlant) and the Plant Metabolome Hub (PMhub) consolidate standard MS/MS and in silico MS/MS spectral data for hundreds of thousands of metabolites across various plant species, significantly enhancing annotation capabilities [11]. These resources, coupled with the application of artificial intelligence and machine learning tools, are transforming how researchers explore chemical diversity in nature and accelerating the discovery of novel compounds with potential applications across pharmaceuticals, nutraceuticals, and agriculture [11] [22].

Diagram 2: Integrated bioprospecting and conservation workflow.

From Lab to Lead: Methodologies and Real-World Applications in Plant Metabolomics

Non-targeted metabolomics has emerged as a powerful approach for comprehensively characterizing the complex chemical profiles of plant systems. This methodology provides a holistic snapshot of the metabolome, capturing dynamic metabolic changes in response to genetics, environment, and stress conditions [23]. The analytical platforms of Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry (LC-HRMS), Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS), and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy form the technological foundation for these investigations, each offering complementary strengths in metabolite separation, detection, and identification.

Each platform possesses distinct capabilities regarding sensitivity, metabolite coverage, and analytical output, making their selection and application crucial for answering specific biological questions in plant chemistry research. This article presents detailed application notes and experimental protocols for these core analytical platforms, providing researchers and drug development professionals with practical frameworks for implementing non-targeted metabolomics in their investigations of plant chemical diversity.

Platform Fundamentals and Comparative Analysis

The selection of an appropriate analytical platform is dictated by the specific research objectives, the chemical properties of target metabolites, and the required depth of metabolome coverage. The following table summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of each major platform.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Major Analytical Platforms in Non-Targeted Plant Metabolomics

| Platform | Metabolite Coverage | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Typical Applications in Plant Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LC-HRMS | Broad range of semi-polar and non-volatile compounds (e.g., phenolics, saponins, lipids) | High sensitivity and resolution; does not require derivatization; capable of detecting thousands of features | Difficulties in identifying unknown compounds; matrix effects can suppress ionization; requires specialized expertise in data processing | Chemical fingerprinting for authentication [24]; discovery of novel natural products [25]; studying plant-insect interactions [20] |

| GC-MS | Volatile and thermally stable compounds; derivatization expands coverage to polar metabolites (e.g., sugars, amino acids, organic acids) | Highly reproducible; robust compound identification using standardized spectral libraries; high sensitivity | Requires derivatization for many metabolites; limited to smaller, volatile, or derivatizable molecules; analysis can be destructive | Profiling primary metabolism [26]; analysis of fruit volatile aromas [27]; seed composition studies [26] |

| NMR | Wide range of metabolites, provided they are present in sufficient concentration | Highly quantitative and reproducible; non-destructive; requires minimal sample preparation; provides structural information | Lower sensitivity compared to MS techniques; limited dynamic range; spectral overlap can complicate analysis | Authenticity and origin verification [28]; metabolic fingerprinting [12]; in vivo analysis of intact tissues via HR-MAS [29] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for LC-HRMS Analysis of Plant Metabolites

LC-HRMS is ideal for characterizing a wide range of semi-polar secondary metabolites in plant tissues, such as phenolics, alkaloids, and terpenes [24] [25].

1. Sample Preparation and Extraction:

- Homogenization: Fresh or frozen plant tissue (e.g., leaf, root) is flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground to a fine powder using a mortar and pestle or a tissue lyser [20] [25].

- Extraction: Transfer approximately 30-50 mg of the homogenized powder into a microcentrifuge tube.

- Add 1.0-1.5 mL of a pre-chilled extraction solvent. A commonly used solvent for comprehensive metabolite extraction is Methyl-tert-butyl-ether:methanol:water in a ratio such as 3:1:1 (v/v/v) [25]. The solvent mixture should include internal standards (e.g., U-13C sorbitol, L-Alanine-d4) for quality control and potential normalization [12].

- Vortex vigorously, then incubate on an orbital shaker (40 rpm) for 45 minutes at 4°C.

- Sonicate the samples in a cold water bath (4°C) for 15 minutes.

- Centrifuge at 10,000-14,000 × g for 10-15 minutes at 4°C to pellet insoluble material [20] [12] [25].

- Analysis Ready: Transfer the supernatant (the metabolite-containing layer) to a new vial. For LC-HRMS, dry the extract under a nitrogen stream or speed vacuum and reconstitute it in a suitable LC-compatible solvent (e.g., methanol/water, 1:1). Filter the reconstituted sample before injection [25].

2. Instrumental Analysis:

- Chromatography: Utilize a UHPLC system with a C18 reversed-phase column (e.g., 2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.7-1.8 µm). A typical mobile phase consists of:

- Mass Spectrometry: Operate the HRMS instrument (e.g., Q-Exactive Orbitrap) in both positive and negative electrospray ionization (ESI) modes to maximize metabolite coverage. Data should be acquired in full-scan mode with a mass range of m/z 100-1500 at a high resolution (e.g., >70,000). Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) MS/MS is performed to obtain fragmentation data for metabolite annotation [24] [25].

3. Data Processing: Process raw data using software (e.g., Compound Discoverer, XCMS) for peak picking, alignment, and normalization. Annotate metabolites by matching accurate mass and MS/MS spectra against databases like mzCloud, GNPS, and in-house libraries, reporting confidence levels per the Metabolomics Standards Initiative (MSI) [24].

Protocol for GC-MS Analysis of Plant Metabolites

GC-MS is highly effective for profiling primary metabolites like sugars, amino acids, and organic acids, which are crucial for understanding plant physiology [27] [26].

1. Sample Preparation and Derivatization:

- Extraction: Weigh 50 mg of ground plant material. Add 0.5 mL of a methanol:chloroform (3:1, v/v) mixture and a known amount of an internal standard (e.g., ribitol). Homogenize using a bead beater, then centrifuge. Collect the polar (upper) phase and dry it completely in a centrifugal concentrator [26].

- Derivatization (Critical Step):

- Methoximation: Add 60 µL of methoxyamine hydrochloride (20 mg/mL in pyridine) to the dried extract and incubate at 80°C for 30 minutes. This step protects carbonyl groups and reduces ring formation in sugars.

- Trimethylsilylation: Add 70 µL of N-Methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (MSTFA) with 1% TMCS as a catalyst. Incubate at 70°C for 1.5 hours. This replaces active hydrogens with a trimethylsilyl group, making metabolites volatile and thermally stable [12] [26].

2. Instrumental Analysis:

- Gas Chromatography: Use an Agilent 7890 GC system equipped with a non-polar DB-5MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 µm). Helium is the carrier gas at a constant flow of 1.0-1.5 mL/min. The temperature program is:

- Mass Spectrometry: Operate the MS with an electron impact (EI) ion source at 70 eV. Acquire data in full-scan mode over a mass range of m/z 50-600. The ion source temperature is typically set to 250°C [27] [26].

3. Data Processing: Use instrument software (e.g., ChromaTOF) and the LECO-Fiehn Rtx5 library or NIST database for peak deconvolution and metabolite identification based on retention index and mass spectral matching [12] [26].

Protocol for NMR Analysis of Plant Metabolites

NMR spectroscopy offers a highly reproducible and quantitative profile of major metabolites in plant samples with minimal sample preparation [28] [30] [29].

1. Sample Preparation for Liquid NMR:

- Extraction: Prepare a hydroalcoholic extract as described in the LC-HRMS protocol. Alternatively, for a more targeted polar metabolite profile, extract ~50 mg of ground tissue with 1 mL of deuterated phosphate buffer (e.g., 100 mM, pD 7.0) in D2O containing 0.5 mM of a chemical shift reference standard like TSP (trimethylsilylpropanoic acid) or DSS (4,4-dimethyl-4-silapentane-1-sulfonic acid) [28] [29].

- Centrifuge at high speed and transfer 600 µL of the supernatant into a standard 5 mm NMR tube.

2. Sample Preparation for HR-MAS NMR (Intact Tissue):

- This method eliminates extraction and allows in vivo-like analysis. Place ~30 mg of fresh or frozen plant tissue directly into a zirconium oxide HR-MAS rotor.

- Add 10-20 µL of D2O for field-frequency locking and a reference compound like TSP [29].