Multi-Omics Validation in Plant Metabolic Engineering: From Pathway Discovery to Clinical Translation

This comprehensive review explores the integration of multi-omics technologies for validating outcomes in plant metabolic engineering.

Multi-Omics Validation in Plant Metabolic Engineering: From Pathway Discovery to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the integration of multi-omics technologies for validating outcomes in plant metabolic engineering. As engineered plants become increasingly important sources of pharmaceuticals and high-value natural products, robust validation frameworks are essential for confirming metabolic alterations and ensuring reproducible results. We examine foundational multi-omics approaches including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics for comprehensive pathway characterization. The article details cutting-edge methodological applications combining computational modeling, artificial intelligence, and experimental techniques to analyze complex metabolic networks. We address critical troubleshooting challenges in data integration, scaling, and optimization, while presenting comparative validation frameworks that assess multi-omics efficacy across diverse case studies. This resource provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with advanced strategies for confirming engineered metabolic outcomes, accelerating the translation of plant-based bioproduction from laboratory discovery to clinical application.

The Multi-Omics Landscape: Core Technologies and Principles for Plant Metabolic Validation

Integrating Genomics, Transcriptomics, Proteomics and Metabolomics for Comprehensive Pathway Analysis

The convergence of genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics has ushered in a transformative era for plant metabolic engineering, enabling unprecedented dissection of complex biological systems. Multi-omics integration represents a paradigm shift from reductionist approaches to a holistic framework that captures the intricate flow of genetic information to functional phenotypes [1]. This comprehensive profiling is particularly vital for validating metabolic engineering outcomes, as it reveals how genetic modifications cascade through molecular layers to influence metabolic endpoints and ultimately produce desired traits in plants [2] [3]. For researchers and drug development professionals, this integrated approach accelerates the discovery of biosynthetic pathways for valuable plant-derived compounds while ensuring engineered metabolic changes function as predicted within the cellular context.

The fundamental power of multi-omics lies in its capacity to bridge genotype-phenotype relationships through sequential analysis of molecular layers. Genomics provides the blueprint of potential metabolic capabilities, transcriptomics captures gene expression dynamics, proteomics identifies functional effectors, and metabolomics reveals the ultimate biochemical outputs [4] [5]. When these datasets are integrated, they form a comprehensive network that elucidates how engineered genetic changes propagate through transcriptional, translational, and post-translational regulation to modulate metabolic flux [1]. This is especially critical in plant metabolic engineering, where interventions aimed at enhancing production of therapeutic compounds or improving crop resilience must be evaluated within the context of the plant's entire metabolic network to avoid unanticipated bottlenecks or compensatory mechanisms [2] [6].

Core Omics Technologies: Principles and Applications

Each omics technology captures a distinct layer of biological information, offering complementary insights into plant metabolic pathways. The table below summarizes the core technologies, their applications, and limitations in plant metabolic engineering research.

Table 1: Core Omics Technologies in Plant Metabolic Pathway Analysis

| Omics Layer | Analytical Platforms | Key Applications in Plant Metabolic Engineering | Technical Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), Oxford Nanopore, Illumina NovaSeq X [7] | Gene discovery, pathway elucidation, identification of biosynthetic gene clusters [6] | Does not capture dynamic regulatory states |

| Transcriptomics | RNA-seq, single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq), Microarrays [4] | Identification of differentially expressed genes under stress conditions, transcriptional network reconstruction [4] | mRNA levels may not correlate with protein abundance |

| Proteomics | Mass spectrometry, SomaScan, Olink, Benchtop sequencers (Platinum Pro) [8] | Protein quantification, post-translational modification analysis, enzyme activity inference [9] | Technical challenges in detecting low-abundance proteins |

| Metabolomics | Mass spectrometry, LC-MS, GC-MS [1] [4] | Metabolic flux analysis, pathway output measurement, identification of novel compounds [3] | Comprehensive coverage challenging due to chemical diversity |

Methodological Details

Genomic techniques have evolved significantly, with Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) platforms like Illumina's NovaSeq X providing unprecedented throughput and cost-effectiveness, while Oxford Nanopore technologies offer long-read capabilities for improved genome assembly [7]. These advances were pivotal in sequencing the genome of Withania somnifera, revealing a conserved gene cluster for withanolide biosynthesis through comparative phylogenomics [6].

Transcriptomic profiling employs either hybridization-based (microarrays) or sequencing-based (RNA-seq) approaches. RNA-seq has emerged as the gold standard due to its high throughput, accuracy, wide detection range, and ability to identify novel transcripts [4]. Single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) represents a cutting-edge advancement that resolves cellular heterogeneity, as demonstrated in studies identifying cell type-specific transcriptional responses to salt stress in Arabidopsis root tips [4].

Proteomic technologies have seen remarkable innovations, including the development of benchtop protein sequencers like Quantum-Si's Platinum Pro, which enables accessible protein analysis without specialized expertise [8]. Mass spectrometry remains a cornerstone technology, with modern platforms capable of capturing entire proteomes in 15-30 minutes [8]. Affinity-based platforms such as SomaScan and Olink facilitate large-scale studies, as evidenced by their use in proteomic investigations of GLP-1 receptor agonists in thousands of participants [8].

Metabolomic platforms leverage advanced mass spectrometry to provide an unbiased detection of diverse metabolite classes, capturing the functional outputs of metabolic pathways [4]. These approaches are essential for quantifying changes in active compound production following genetic modifications, as demonstrated in studies measuring medicinal compounds like matrine and oxymatrine in Sophora tonkinensis under varying nutrient conditions [3].

Multi-Omics Data Integration Methodologies

Computational Integration Approaches

Integrating diverse omics datasets requires sophisticated computational strategies that can accommodate different data structures, scales, and biological meanings. The primary integration methodologies include:

Statistical and enrichment approaches employ quantitative methods to identify coordinated changes across omics layers. Tools like Integrated Molecular Pathway-Level Analysis (IMPaLA) and MultiGSEA compute pathway enrichment scores that aggregate signals from multiple omics datasets, providing statistical significance for pathway activities [5]. These methods are particularly valuable for initial screening of multi-omics data to identify significantly altered biological processes.

Network-based approaches construct biological networks that incorporate multiple types of molecular interactions. Topology-based methods like Signaling Pathway Impact Analysis (SPIA) and Oncobox consider the biological reality of pathways by incorporating data on the type and direction of protein interactions, which has been shown to outperform non-topology methods in benchmarking tests [5]. These approaches calculate Pathway Activation Levels (PALs) by integrating gene expression data with curated pathway topology databases, providing a more realistic picture of pathway dysregulation [5].

Machine learning approaches utilize both supervised and unsupervised algorithms to identify patterns in integrated omics data. Supervised learning techniques, such as DIABLO, use phenotype groups as class labels to predict pathway activities based on integrated multi-omics data [5]. Unsupervised learning methods, including clustering and principal component analysis (PCA), discover latent features and patterns without predefined labels, helping researchers identify novel associations between molecular layers [5].

Table 2: Multi-Omics Data Integration Methods and Applications

| Integration Method | Representative Tools | Key Advantages | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical/Enrichment | IMPaLA, MultiGSEA, PaintOmics [5] | Straightforward interpretation, cross-validation across omics layers | Initial screening studies, biomarker identification |

| Network-Based | SPIA, Oncobox, iPANDA [5] | Incorporates biological context of pathway topology | Pathway analysis, drug target identification |

| Machine Learning | DIABLO, OmicsAnalyst [5] | Identifies complex, non-linear relationships across omics layers | Predictive modeling, pattern discovery in large datasets |

Workflow Visualization

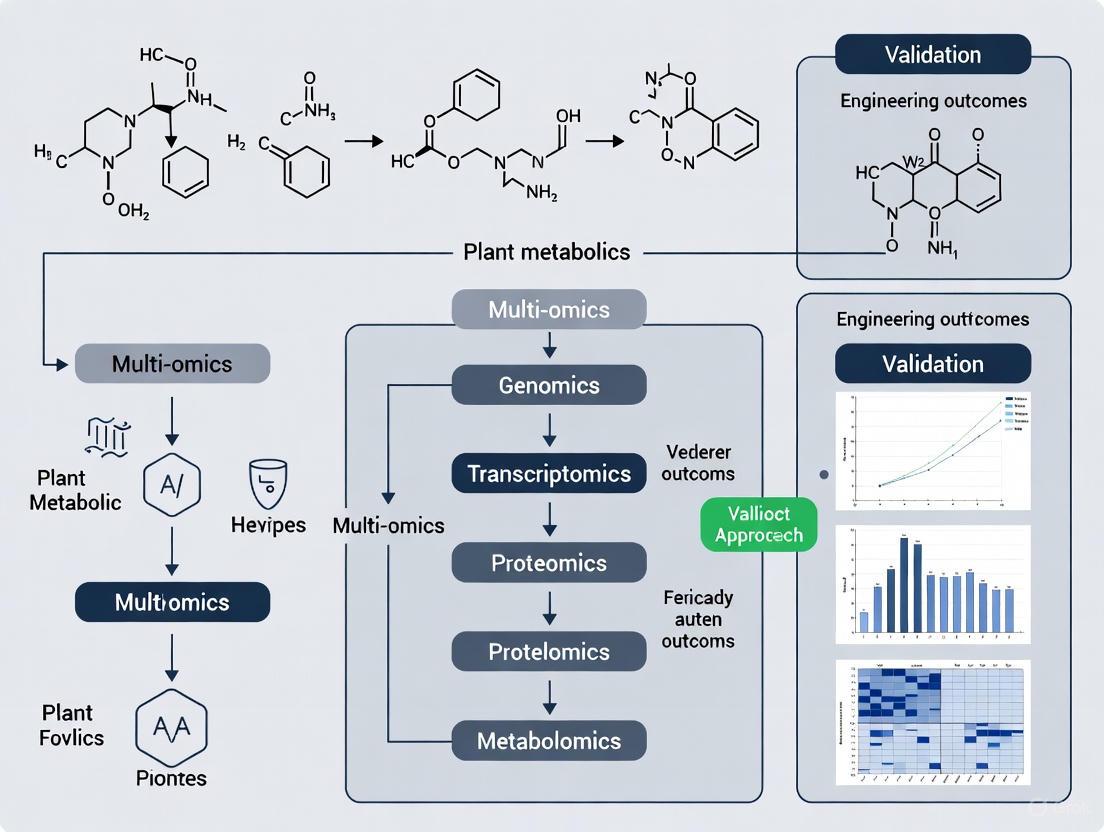

The following diagram illustrates a generalized multi-omics integration workflow for plant metabolic pathway analysis, from experimental design through data integration and biological interpretation:

Experimental Applications in Plant Metabolic Engineering

Case Study 1: Elucidating Withanolide Biosynthesis

A landmark application of multi-omics in plant metabolic engineering involved the discovery of the withanolide biosynthetic pathway in Withania somnifera (ashwagandha) [6]. Withanolides are steroidal lactones with significant pharmaceutical potential, but their biosynthetic pathway remained largely unknown, hampering biotechnological production.

Experimental Approach: Researchers employed an integrated phylogenomics and metabolic engineering strategy. First, they sequenced the genome of Withania somnifera using Oxford Nanopore technology, generating a high-quality assembly of 2.88 Gbp with 34,955 protein-encoding genes [6]. Comparative genomic analysis with nine other Solanaceae species revealed a conserved biosynthetic gene cluster containing cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (CYPs), 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases (ODDs), short-chain dehydrogenases/reductases (SDRs), and the previously identified sterol Δ24-isomerase (24ISO) [6].

Functional Validation: The team established two independent metabolic engineering platforms for functional validation: a yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) system and a plant (Nicotiana benthamiana) transient expression system [6]. Through systematic pathway reconstitution, they characterized three cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (CYP87G1, CYP88C7, and CYP749B2) and a short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase that collectively catalyze the first five oxidations of withanolide biosynthesis, constructing the pivotal δ-lactone ring structure [6].

Multi-Omics Integration: Genomic data identified candidate genes, transcriptomic analysis confirmed coordinated expression, and metabolic profiling verified the production of expected compounds in the engineered systems. This multi-omics approach successfully bridged the gap between gene discovery and functional validation, enabling the engineering of withanolide biosynthesis in heterologous systems [6].

Case Study 2: Magnesium Regulation of Medicinal Compounds

Another compelling application investigated how magnesium ions regulate the synthesis of active ingredients in Sophora tonkinensis, a medicinal plant containing valuable compounds like matrine, oxymatrine, maackiain, and trifolirhizin [3].

Experimental Design: Researchers treated tissue-cultured seedlings with varying magnesium concentrations (0-4 mM MgSO₄) over 60 days, then conducted integrated transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic analyses [3]. Phenotypic measurements included plant height, stem diameter, leaf count, rooting rate, root length, and root dry weight. Active ingredient content was quantified using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) with specific extraction protocols and chromatographic conditions [3].

Multi-Omics Workflow:

- Metabolomic Analysis: Measured changes in active compound levels using HPLC with C18 columns and acetonitrile-water gradient elution [3].

- Transcriptomic Profiling: RNA sequencing identified differentially expressed genes across magnesium treatments [3].

- Proteomic Analysis: Quantified protein expression changes in response to magnesium availability [3].

- Data Integration: Combined datasets to reconstruct magnesium's influence on metabolic networks [3].

Key Findings: The integrated analysis revealed that magnesium exerts pervasive effects on multiple metabolic pathways, forming an intricate regulatory network. Magnesium influenced potassium and calcium absorption, photosynthetic activity, and ultimately altered the concentrations of pharmacologically active compounds [3]. This systems-level understanding provides crucial insights for optimizing cultivation conditions to enhance medicinal compound production.

Essential Research Tools and Reagents

Successful multi-omics studies require a comprehensive toolkit of bioinformatics resources, analytical platforms, and specialized reagents. The following table catalogues essential solutions for researchers designing multi-omics investigations in plant metabolic engineering.

Table 3: Essential Research Solutions for Multi-Omics Pathway Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Key Features | Applications in Multi-Omics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatics Platforms | Bioconductor, Galaxy, Oncobox [10] [5] | R-based packages (Bioconductor), workflow management (Galaxy), pathway activation scoring (Oncobox) | Statistical analysis, data integration, pathway activation assessment |

| Sequence Analysis | BLAST, Clustal Omega, MAFFT, DeepVariant [10] | Sequence similarity searching (BLAST), multiple sequence alignment (Clustal Omega, MAFFT), variant calling (DeepVariant) | Gene annotation, phylogenetic analysis, mutation detection |

| Pathway Databases | KEGG, OncoboxPD [10] [5] | Curated pathway information (KEGG), customized pathway databank with 51,672 human pathways (OncoboxPD) | Pathway mapping, network construction, functional annotation |

| Protein Structure Prediction | Rosetta [10] | AI-driven protein structure prediction and design | Enzyme engineering, metabolic pathway design |

| Specialized Reagents | SomaScan, Olink, Ultima UG 100 [8] | Affinity-based proteomics (SomaScan, Olink), high-throughput sequencing (Ultima UG 100) | Large-scale proteomic studies, population-scale sequencing |

The integration of genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics represents a transformative approach for comprehensive pathway analysis in plant metabolic engineering. By capturing information across multiple molecular layers, researchers can now obtain systems-level understanding of how genetic modifications influence metabolic outcomes, enabling more precise engineering of valuable compounds in plants [1] [2]. The case studies presented demonstrate how this integrated approach successfully bridges the gap between gene discovery and functional validation, accelerating the development of plant-based production systems for medicinal compounds [3] [6].

Future advancements in multi-omics integration will likely be driven by improvements in artificial intelligence, single-cell technologies, and spatial omics. The incorporation of AI and machine learning is already enhancing data integration capabilities, with tools like DeepVariant demonstrating superior performance in variant calling [7] [10]. Single-cell multi-omics approaches are revealing cellular heterogeneity in plant tissues, providing unprecedented resolution for understanding specialized metabolism [4]. Spatial transcriptomics and metabolomics technologies are adding crucial contextual information by mapping molecular events within tissue architecture [4] [8]. As these technologies mature and computational integration methods become more sophisticated, multi-omics approaches will increasingly enable predictive modeling of plant metabolic systems, fundamentally advancing our capacity to engineer plants for improved production of pharmaceuticals, enhanced nutritional quality, and greater resilience to environmental challenges [1] [2].

In the realm of plant metabolic engineering, validating successful engineering outcomes requires a comprehensive analysis of the resulting metabolic changes. Advanced analytical platforms including Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS/MS), and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy provide complementary capabilities for thorough metabolite profiling. These techniques form the technological cornerstone of multi-omics research, enabling researchers to decipher the complex biochemical networks that govern plant growth, development, and environmental adaptation [11]. The integration of data from these platforms offers unprecedented insights into how genetic modifications translate to metabolic phenotypes, thereby closing the loop between engineering interventions and functional validation.

The fundamental challenge in plant metabolomics lies in the astounding chemical diversity of plant metabolites, estimated to exceed 200,000 compounds across the plant kingdom, with individual species containing 7,000-15,000 different metabolites [11]. These metabolites exhibit vast variations in concentration, chemical stability, and spatial distribution within plant tissues. This review provides a comparative analysis of LC-MS/MS, GC-MS/MS, and NMR platforms, highlighting their respective strengths, limitations, and applications within integrated multi-omics frameworks for validating plant metabolic engineering outcomes.

Technology Platform Comparison

Core Technical Characteristics

The selection of an appropriate analytical platform depends on the specific research questions, target metabolites, and required data quality. LC-MS/MS, GC-MS/MS, and NMR offer complementary capabilities with distinct technical operating principles.

Table 1: Core Technical Characteristics of Major Analytical Platforms in Metabolite Profiling

| Parameter | LC-MS/MS | GC-MS/MS | NMR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | High (nanomolar to picomolar) [11] | High [11] | Low (micromolar to millimolar) [12] [13] |

| Analytical Reproducibility | Average [13] | Average | Very High [13] |

| Number of Detectable Metabolites | 300-1000+ [13] | 300-1000+ [13] | 30-100 [13] |

| Sample Preparation Complexity | More complex preparation required [13] | More complex preparation required [13] | Minimal preparation required [13] |

| Tissue Analysis | Requires extraction [13] | Requires extraction [13] | Direct analysis possible [13] |

| Analysis Time Per Sample | Longer (chromatography dependent) [13] | Longer (chromatography dependent) [13] | Fast (single measurement) [13] |

| Metabolite Identification Confidence | High with MS/MS libraries | High with MS/MS libraries | Definitive structural elucidation |

| Quantitative Capability | Excellent with proper standards | Excellent with proper standards | Excellent (absolute quantification) |

| Key Strengths | Broad metabolite coverage, high sensitivity, structural information via MS/MS | Excellent for volatiles and derivatized compounds, robust databases | Non-destructive, absolute quantification, minimal sample preparation, structural elucidation |

| Key Limitations | Matrix effects, ion suppression, requires chromatography | Derivatization required for many metabolites, thermal degradation possible | Lower sensitivity, limited metabolite coverage, spectral overlap |

Experimental Evidence of Complementary Metabolite Coverage

The complementary nature of these platforms is clearly demonstrated in practical studies. A comparative investigation analyzing Chlamydomonas reinhardtii metabolomes revealed significant differences in metabolite detection capabilities between techniques [12]. The study identified 102 metabolites in total: 82 by GC-MS alone, 20 by NMR alone, and 22 by both techniques [12]. This demonstrates that each platform accesses unique aspects of the metabolome.

Specifically, NMR uniquely detected key glycolytic intermediates including fructose, glycerol, and pyruvate, while fructose-6-phosphate was exclusively identified by GC-MS [12]. For amino acid analysis, all 20 proteinogenic amino acids were detected across platforms, but with distinct coverage: asparagine, cysteine, histidine, serine, and tryptophan were only observed by GC-MS, while glycine, lysine, methionine, and valine were unique to NMR [12]. This experimental evidence underscores the necessity of combining multiple analytical techniques to achieve comprehensive metabolome coverage in plant metabolic engineering validation studies.

Experimental Protocols for Integrated Metabolite Profiling

Sample Preparation Workflow

Proper sample preparation is critical for reliable metabolomic data. The general workflow encompasses several standardized stages:

Sample Collection and Quenching: Rapid quenching of metabolism is essential for capturing accurate metabolic snapshots. Methods include flash freezing in liquid N₂, using chilled methanol (-20°C or -80°C), or ice-cold PBS. Quick processing is vital to prevent metabolic deviations from the physiological state of interest [14].

Metabolite Extraction: Efficient extraction separates metabolites from proteins and other macromolecules. Liquid-liquid extraction with biphasic solvent systems is commonly employed:

- Methanol/chloroform/water mixtures enable simultaneous extraction of polar metabolites (methanol/water phase) and non-polar lipids (chloroform phase) [14].

- Solvent ratios are adjusted based on target metabolites; 100% methanol or 9:1 methanol:chloroform is preferred for highly polar metabolites, while traditional 2:1 methanol:chloroform ratios provide balanced extraction [14].

- Internal standards (typically stable isotope-labeled compounds) are added prior to extraction to correct for variability and enable accurate quantification [14].

Sample Analysis Preparation:

- For LC-MS/MS: Extracts are reconstituted in MS-compatible solvents (e.g., water, methanol, acetonitrile) [11].

- For GC-MS/MS: Chemical derivatization (e.g., silylation) is often necessary to increase volatility and thermal stability of metabolites [11].

- For NMR: Minimal additional preparation is needed; samples may be dissolved in deuterated solvents for lock signal [13].

Data Acquisition and Processing Strategies

Each platform requires specific data acquisition and processing approaches to maximize information quality:

LC-MS/MS: Utilizes reverse-phase, HILIC, or other chromatographic separations coupled to high-resolution mass spectrometers (e.g., Q-TOF, Orbitrap). Data-dependent acquisition (DDA) or data-independent acquisition (DIA) methods are employed to collect MS/MS spectra for metabolite identification [11] [15]. Advanced data mining techniques include mass defect filters (MDF), product ion filters (PIF), and background subtraction to facilitate metabolite detection [15] [16].

GC-MS/MS: Employes high-efficiency capillary columns with electron ionization (EI) sources. EI generates reproducible fragmentation patterns, enabling library matching against standardized databases [11].

NMR: Typically utilizes 1D ¹H or 2D ¹H-¹³C HSQC experiments. NMRpipe and NMRviewJ are commonly used for processing, with metabolite assignments performed using spectral databases such as the Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank (BMRB) [12].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated application of these platforms in a multi-omics context for plant metabolic engineering validation:

Figure 1: Integrated Multi-Platform Workflow for Validating Plant Metabolic Engineering Outcomes

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful metabolite profiling requires carefully selected reagents and materials optimized for each analytical platform.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolite Profiling

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Methanol (MeOH) | Polar solvent for metabolite extraction [14] | Effective for polar metabolites; often used in combination with chloroform or water for biphasic extraction |

| Chloroform (CHCl₃) | Non-polar solvent for lipid extraction [14] | Used in biphasic systems with methanol/water; classical Folch and Bligh & Dyer methods for lipid extraction |

| Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) | Non-polar solvent for lipid extraction [14] | Alternative to chloroform; high affinity for lipophilic metabolites |

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., D₂O, CD₃OD) | NMR solvent providing lock signal [12] | Enables NMR frequency stabilization; minimal interference with metabolite signals |

| Derivatization Reagents (e.g., MSTFA) | Increases volatility for GC-MS analysis [17] | Silylation reagents protect functional groups and enhance thermal stability |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Quantification reference and quality control [14] | Corrects for extraction and ionization variability; essential for accurate quantification |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | Mobile phase for chromatography [11] | High purity minimizes background signals and ion suppression in MS |

| NMR Reference Standards | Chemical shift calibration [12] | Compounds like TMS (tetramethylsilane) provide reference points for spectral alignment |

Integration with Multi-Omics Frameworks for Plant Metabolic Engineering

Metabolite profiling data from LC-MS/MS, GC-MS/MS, and NMR becomes particularly powerful when integrated with other omics data within mathematical modeling frameworks. This integrated approach is essential for moving beyond descriptive observations to predictive understanding in plant metabolic engineering.

Constraint-Based Models (CBMs), including Genome-Scale Metabolic models (GEMs), utilize metabolomics data to define boundaries and predict metabolic flux distributions [18]. These models can predict how genetic modifications will affect overall metabolic network behavior, enabling in silico testing of engineering strategies before implementation. For instance, FBA has been used to identify key metabolic reactions and potential targets for enhancing crop yield, stress tolerance, and nutritional quality [18].

Kinetic models incorporate enzyme kinetic parameters to simulate dynamic metabolic behaviors [18]. While more computationally intensive and parameter-demanding, these models can provide insights into transient metabolic responses to genetic perturbations. The integration of multi-omics data into these modeling frameworks creates a powerful cycle of hypothesis generation and testing, accelerating the optimization of plant metabolic engineering strategies.

The complementary use of visualization strategies throughout the multi-omics analysis pipeline enhances data interpretation and hypothesis generation. As highlighted in recent reviews, effective data visualization is crucial for navigating complex metabolomic datasets, with techniques including volcano plots, cluster heatmaps, and network visualizations enabling researchers to identify patterns and relationships that might be overlooked in purely statistical analyses [19].

LC-MS/MS, GC-MS/MS, and NMR spectroscopy provide complementary analytical capabilities that collectively enable comprehensive metabolite profiling for plant metabolic engineering validation. While LC-MS/MS offers broad coverage and high sensitivity, GC-MS/MS excels in analyzing volatile and derivatizable compounds, and NMR provides definitive structural information and absolute quantification with minimal sample workup. The experimental evidence clearly demonstrates that integrating these platforms significantly expands metabolome coverage and enhances confidence in metabolite identification.

As plant metabolic engineering continues to advance toward increasingly ambitious goals—including enhanced nutritional content, improved stress resilience, and sustainable production of valuable phytochemicals—the strategic combination of these analytical platforms within multi-omics frameworks will be essential for validating engineering outcomes and guiding future engineering strategies. The continued development of integrated workflows, data visualization tools, and computational modeling approaches will further strengthen our ability to connect genetic modifications to metabolic phenotypes, accelerating the engineering of improved plant systems.

In the field of plant metabolic engineering, validating engineered metabolic pathways and predicting their behavior in whole plants requires sophisticated, controlled model systems. Callus, hairy root, and suspension cultures have emerged as three foundational in vitro platforms that provide standardized environments for testing genetic constructs and evaluating metabolic outcomes [20]. These systems bridge the gap between microbial models and whole-plant studies, offering the unique advantages of plant-specific metabolic machinery while maintaining the controllability essential for rigorous scientific experimentation.

The integration of these culture systems with multi-omics technologies (transcriptomics, metabolomics, and hormonome analysis) enables researchers to capture comprehensive snapshots of cellular states following genetic modifications [21] [22]. This article provides a comparative analysis of these three culture platforms, examining their applications in validating plant metabolic engineering outcomes, with specific experimental data and protocols to guide researchers in selecting appropriate systems for their work.

Comparative Analysis of Plant Culture Platforms

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and applications of callus, suspension, and hairy root cultures as validation environments in plant metabolic engineering research.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of plant culture systems for metabolic engineering validation

| Parameter | Callus Culture | Suspension Culture | Hairy Root Culture |

|---|---|---|---|

| Developmental State | Undifferentiated cell mass [23] | Undifferentiated single cells or small aggregates in liquid medium [23] | Differentiated, genetically transformed root organs [24] [25] |

| Growth Pattern | Solid medium surface, organized clusters | Homogeneous liquid culture with agitation | Branched root morphology, hormone-independent growth [20] |

| Key Applications | Initial transformation, preliminary metabolite screening, callus-based selection | Large-scale metabolite production, elicitation studies, bioreactor scaling [20] | Root-specific metabolism, pathway validation, stable metabolite production [24] [25] |

| Transformation Efficiency | Varies by species and explant (e.g., 68.18% in Verbascum leaf explants) [24] | Dependent on callus source; not typically direct transformation target | High with optimized protocols (e.g., 80.55% in Verbascum with A13 strain) [24] |

| Metabolic Stability | Variable, may undergo somaclonal variation | Moderate, requires monitoring for phenotypic drift | High genetic and metabolic stability [26] |

| Experimental Scalability | Moderate (solid medium surface area limited) | High (compatible with bioreactor systems) [20] | Moderate (structured morphology limits large-scale culture) |

| Multi-omics Integration | Transcriptome and metabolome profiling under controlled conditions [21] | Comprehensive metabolome, transcriptome, and hormonome analysis [21] | Transcriptomic and metabolomic analysis of root-specific pathways |

Experimental Protocols for Culture Establishment and Validation

Callus Culture Induction and Multi-omics Analysis

Protocol for Establishment and Analysis:

- Explant Preparation: Surface-sterilize leaf segments or hypocotyls from donor plants [24].

- Culture Initiation: Place explants on solid Linsmaier and Skoog or Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium supplemented with auxins (e.g., 1 µM 2,4-D or 10 µM picloram) and 0.3% gellan gum [21].

- Growth Conditions: Maintain at 25°C with a 16-h light/8-h dark photoperiod or in complete darkness, depending on species requirements [21].

- Multi-omics Sampling: Harvest callus tissue weekly over 4 weeks. Divide samples for transcriptome (freeze in liquid nitrogen), metabolome (freeze-dry), and hormonome analysis [21].

- Environmental Manipulation: Apply different airflow conditions using Parafilm M (complete sealing) or Micropore Surgical Tape (ventilated sealing) to study environmental effects [21].

Hairy Root Culture Induction and Optimization

Protocol for Establishment and Analysis:

- Bacterial Preparation: Grow Agrobacterium rhizogenes strains (e.g., ATCC 15834, A4, A7, A13) in YEB liquid medium for 24 hours [24] [25].

- Plant Transformation: Inoculate leaf explants (21-day-old optimal) by direct infection with 3 wounds using a syringe needle, followed by 72 hours co-cultivation [24].

- Antibiotic Selection: Transfer explants to MS medium with cefotaxime (500 mg/L) to eliminate bacteria, reducing to 250 mg/L after root emergence [25].

- Culture Maintenance: Establish roots in liquid MS medium without hormones, culture in darkness at 23°C with agitation (90 rpm) [25].

- Transformation Confirmation: Verify integration of T-DNA using PCR with rolB and rolC specific primers (780 bp product for rolB) [24].

- Metabolite Quantification: Analyze secondary metabolites (e.g., salidroside and rosavin in Rhodiola quadrifida) via HPLC-MS at stationary growth phase [25].

Suspension Culture Establishment from Friable Callus

Protocol for Establishment and Analysis:

- Inoculum Preparation: Transfer friable callus (approximately 500 mg fresh weight) to liquid medium in flasks [21] [23].

- Culture Conditions: Maintain on rotary shakers (90-120 rpm) in dark at 25°C, subculture every 2-3 weeks [23].

- Growth Monitoring: Measure packed cell volume and cell density using hemocytometer to track growth cycles [23].

- Elicitor Studies: Apply jasmonic acid, methyl jasmonate, or other elicitors to enhance secondary metabolite production [23].

- Metabolite Profiling: Use widely targeted metabolomics with LC-QqQMS to quantify hundreds of metabolites during growth cycle [21].

Signaling Pathways and Regulatory Networks in Culture Systems

The diagram below illustrates the integrated signaling pathways and regulatory networks that govern metabolic responses in plant culture systems, highlighting key phytohormones and their interactions.

Diagram 1: Signaling pathways regulating metabolic responses in plant culture systems

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for plant culture studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Murashige and Skoog (MS) Medium | Basal nutrient medium providing essential macro and micronutrients [25] | Foundation for callus, suspension, and hairy root cultures [21] [25] |

| 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) | Synthetic auxin for callus induction and maintenance [23] | Callus induction from leaf explants (1 µM for tobacco, 10 µM picloram for rice/bamboo) [21] |

| Agrobacterium rhizogenes Strains | Bacterial vector for hairy root induction via Ri plasmid transfer [24] [26] | Root transformation (A13 strain shown most effective for Verbascum) [24] |

| Cefotaxime | Antibiotic for eliminating Agrobacterium after transformation [24] | Added to medium (250-500 mg/L) after co-cultivation period [25] |

| Jasmonic Acid/Methyl Jasmonate | Elicitors that stimulate defense responses and secondary metabolism [23] [20] | Enhanced flavonoid production in suspension cultures [23] |

| Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) | Metabolite profiling and quantification [21] [22] | Widely targeted metabolomics (442 metabolites), phytohormone analysis (31 hormones) [21] |

| RNA Sequencing Library Prep Kits | Transcriptome analysis of culture systems [21] | RNA-seq library preparation (NEXTFLEX Rapid Directional RNA-Seq Kit) [21] |

Multi-Omics Integration in Culture System Validation

The workflow below illustrates how multi-omics approaches are integrated with plant culture systems to validate metabolic engineering outcomes.

Diagram 2: Multi-omics workflow for validating metabolic engineering in culture systems

Advanced multi-omics approaches enable comprehensive validation of metabolic engineering outcomes in plant culture systems. Integrated transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses reveal gene-to-metabolite association networks, identifying key regulatory points in engineered pathways [22]. For example, in ginseng fruit studies, multi-omics dissection identified MYB, bHLH, and ERF transcription factors as key regulators of metabolic shifts during development [22]. In engineered culture systems, such approaches can distinguish between successful pathway engineering and compensatory cellular responses.

Hormonome profiling provides crucial insights into the phytohormonal regulation of engineered pathways, quantifying 31 key hormones using UPLC-ESI-qMS/MS and UHPLC-Orbitrap MS platforms [21]. This is particularly valuable when engineering pathways connected to hormone signaling or when culture conditions alter endogenous hormone balances.

Callus, suspension, and hairy root cultures provide complementary platforms for validating plant metabolic engineering outcomes in controlled environments. Each system offers distinct advantages: callus cultures for initial screening, suspension cultures for scalable production and multi-omics integration, and hairy root cultures for root-specific metabolism and stable compound production [20].

The integration of these culture systems with multi-omics technologies creates a powerful framework for predictive biology in plant metabolic engineering. By providing comprehensive molecular snapshots of engineered systems, these approaches enable researchers to verify pathway functionality, identify bottlenecks, and detect unintended metabolic consequences before transitioning to whole plants. As these technologies continue to advance, they will accelerate the development of plant-based bioproduction platforms for pharmaceuticals, nutraceuticals, and valuable natural products [27] [20].

In the field of plant metabolic engineering, validating successful engineering outcomes requires a comprehensive view of the plant's molecular state. Data harmonization across multiple omics layers (e.g., genomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics) and experimental cohorts is the foundational bioinformatics process that makes this possible. It transforms disparate, siloed datasets into a cohesive and comparable resource, enabling researchers to move from simple correlations to true mechanistic understanding. This guide objectively compares the performance of leading harmonization methodologies, providing a framework for selecting the right tools to confirm that genetic modifications have produced the intended metabolic results.

The Critical Challenge of Multi-Omics Data Harmonization

Biological systems are inherently complex, and capturing their full scope requires reconciling data with varying formats, scales, and biological contexts [28]. In plant metabolic engineering, a researcher might have genomic data from sequenced mutants, transcriptomic data from RNA-seq experiments, and metabolomic profiles from LC-MS—all from different plant tissues, growth conditions, or even related species. Data harmonization is the practice of combining these different datasets to maximize their comparability and compatibility [29].

The core challenges in harmonization occur across three dimensions:

- Syntax: Differences in technical data formats (e.g.,

.csvvs. JSON files) [29]. - Structure: Differences in conceptual schema, such as data organized by experimental event versus data organized by daily sample (panel data) [29].

- Semantics: Differences in the intended meaning of terms, where the same word can describe different concepts or different words can describe the same concept [29].

Without robust harmonization, integrated analyses are built on a shaky foundation, leading to irreproducible results and flawed conclusions about the efficacy of a metabolic engineering strategy.

Comparative Analysis of Multi-Omics Integration Methods

The choice of data integration method directly impacts the biological insights one can derive. The following table compares two broad classes of approaches—statistical and deep learning-based—as evaluated in a benchmark study on breast cancer subtyping, a task analogous to identifying distinct metabolic phenotypes in plants [30].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Statistical vs. Deep Learning-Based Integration for Biological Subtyping

| Feature | Statistical-Based (MOFA+) | Deep Learning-Based (MOGCN) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Approach | Unsupervised factor analysis using latent factors to capture variation across omics [30]. | Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) with autoencoders for dimensionality reduction [30]. |

| Key Strength | High interpretability of latent factors; effective feature selection [30]. | Capability to model complex, non-linear relationships within and between omics layers [30]. |

| Subtyping F1-Score (Non-linear Model) | 0.75 [30] | Lower than MOFA+ [30] |

| Biological Pathway Relevance | Identified 121 key pathways relevant to breast cancer heterogeneity [30] | Identified 100 relevant pathways [30] |

| Best-Suited For | Exploratory analysis, robust feature selection, and studies prioritizing biological interpretability [30]. | Problems with high non-linearity where data structure can be effectively captured as a network [30]. |

This comparative analysis demonstrates that advanced deep learning methods do not always outperform classical statistical approaches. The optimal choice depends on the specific analytical goal, whether it is identifying key driver genes and metabolites in a pathway (where MOFA+'s feature selection excels) or modeling highly complex interactions.

Emerging Tools and Advanced Methodologies

The field is rapidly evolving with new tools designed to overcome the limitations of existing methods. Frameworks like Flexynesis have been developed to bring modularity, transparency, and multi-task learning (e.g., jointly predicting yield and disease resistance) to deep learning-based multi-omics integration [31]. Furthermore, natural language processing (NLP) offers a powerful solution to the semantic challenges in harmonization. One study achieved 98.95% top-5 accuracy in mapping disparate variable descriptions to unified medical concepts using a neural network model with biomedical domain-specific embeddings (BioBERT) [32]. This approach can be directly adapted to harmonize inconsistent metabolite or gene names across plant databases.

Table 2: Key Computational Tools for Multi-Omics Data Harmonization and Integration

| Tool Name | Category | Primary Function | Application in Plant Metabolic Engineering |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOFA+ [30] | Statistical Integration | Unsupervised discovery of latent factors across omics data. | Identify coordinated gene-metabolite modules in engineered versus wild-type plants. |

| Flexynesis [31] | Deep Learning Toolkit | Flexible, modular deep learning for classification, regression, and survival analysis. | Predict complex engineering outcomes like stress tolerance or yield from multi-omics inputs. |

| NLP Harmonizer [32] | Semantic Harmonization | Automatically maps variable names to unified concepts using BioBERT. | Standardize metabolite identifiers and gene nomenclature across public and private datasets. |

| Galaxy [33] | Workflow Platform | User-friendly, web-based platform with drag-and-drop tools and shared data libraries. | Enable reproducible multi-omics analysis pipelines without command-line expertise. |

Experimental Protocols for Robust Harmonization

Implementing a rigorous harmonization protocol is essential for valid results. The following workflow, derived from successful multi-omics studies, provides a template.

Diagram 1: Multi-omics harmonization and integration workflow.

Protocol for Syntax and Structural Harmonization

Step 1: Data Collation Gather raw data from all omics layers (e.g., genome, transcriptome, metabolome) and cohorts. Store them in a structured project directory with consistent naming conventions [34].

Step 2: Format Standardization Convert all data matrices into a common, analysis-ready format (e.g., tab-separated values). Ensure rows consistently represent features (genes, metabolites) and columns represent samples [29].

Step 3: Batch Effect Correction Identify technical artifacts (e.g., from different sequencing batches or harvest days) using methods like ComBat (from the Surrogate Variable Analysis (SVA) package) or Harman [30]. This step is critical for combining data from different experiments or cohorts.

Protocol for Semantic Harmonization and Integration

Step 1: Metadata Annotation Create a detailed data dictionary. Map all feature IDs (e.g., "GeneA," "Solyc02g...") to standard database identifiers (e.g., UniProt, KEGG, PlantCyc) [34] [35].

Step 2: Concept Unification Use an NLP-based tool or manual curation to align metadata variable descriptions. For example, map "plantheightcm," "Height," and "stemlength" to a unified concept like "plantheight" [32].

Step 3: Integrated Data Analysis Apply the chosen integration method (e.g., MOFA+ or Flexynesis) to the harmonized dataset. The following diagram illustrates the logical structure of a multi-omics integration model.

Diagram 2: Logical structure of a multi-omics integration model.

Successful multi-omics harmonization relies on both computational tools and curated biological resources. The following table lists key "reagent solutions" for plant metabolic engineering studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Multi-Omics Studies

| Item Name | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Genome | Provides a standardized coordinate system for mapping genomic and transcriptomic features. | Aligning RNA-seq reads and calling genetic variants in an engineered plant line [34]. |

| Metabolomics Database | Libraries for metabolite identification and annotation (e.g., KEGG, PlantCyc). | Annotating LC-MS peaks to identify targeted and untargeted metabolites in plant extracts [34]. |

| Curated Pathway Database | Defines known biochemical pathways and gene-metabolite relationships. | Interpreting integrated data by mapping coordinated gene-metabolite changes to specific pathways like flavonoid biosynthesis [36] [35]. |

| Bio-BERT / NLP Model | Pre-trained language model for biomedical and life sciences text. | Automating the harmonization of inconsistent gene and metabolite names across lab notebooks and public datasets [32]. |

Data harmonization is not merely a technical pre-processing step but a critical, foundational component of robust multi-omics research. The choice of harmonization and integration methodology—whether a highly interpretable statistical model like MOFA+ or a flexible deep learning framework like Flexynesis—directly shapes the biological validity of the conclusions drawn. For plant metabolic engineers, adopting these rigorous practices is paramount for truly validating that introduced genetic changes have produced the intended, system-wide metabolic outcomes, thereby accelerating the development of improved crops and valuable plant-based products.

From Data to Discovery: Multi-Omics Workflows and AI-Driven Analytical Frameworks

Computational metabolic modeling provides a powerful mathematical framework for simulating the complex biochemical networks within cells, enabling the prediction of metabolic fluxes—the rates at which metabolites flow through pathways. In the context of plant metabolic engineering, these models are indispensable for bridging the gap between genetic modifications and phenotypic outcomes, thereby guiding strategies for enhancing the production of valuable compounds, improving crop resilience, and understanding plant-microbe interactions. The two predominant approaches for flux prediction are Constraint-Based Modeling, including methods like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs), and Kinetic Modeling. Each methodology offers distinct advantages and faces specific limitations, making them suitable for different types of biological questions and available data. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these approaches, focusing on their application in validating plant metabolic engineering outcomes through multi-omics research. By integrating transcriptomic, metabolomic, and proteomic data, these models transform static molecular inventories into dynamic, predictive understanding of plant metabolic behavior, ultimately accelerating the engineering of plants for sustainability and human health [37] [38].

Comparative Analysis of Modeling Approaches

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, applications, and data requirements of the primary modeling approaches discussed in this guide.

Table 1: Comparison of Constraint-Based and Kinetic Metabolic Modeling Approaches

| Feature | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Enzyme-Constrained GEMs (e.g., ECMpy) | Kinetic Modeling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Uses stoichiometric matrix & linear programming to optimize an objective function (e.g., biomass) at steady-state [39] [38]. | Extends FBA by incorporating enzyme turnover numbers (Kcat) and mass constraints to limit flux [39]. | Uses differential equations based on enzyme kinetics and metabolite concentrations to model dynamic behavior [38]. |

| Primary Use Case | Predicting growth rates, flux distributions in large networks, and outcomes of gene knockouts [39] [38]. | Providing more realistic flux predictions by accounting for enzyme capacity and proteome limitations [39]. | Modeling transient metabolic responses, understanding pathway regulation, and identifying control points [38]. |

| Key Advantages | Requires only the network stoichiometry; computationally efficient for genome-scale models; no need for kinetic parameters [39] [38]. | Reduces solution space and avoids unrealistic high flux predictions without drastically increasing model complexity [39]. | Captures time-dependent and non-linear behaviors; provides insight into metabolite concentration changes. |

| Key Limitations | Assumes steady-state; cannot predict metabolite concentrations; relies on a biologically relevant objective function [39]. | Dependent on availability and accuracy of enzyme kinetic data (Kcat); transporters often poorly constrained [39]. | Requires extensive and difficult-to-measure kinetic parameters; not scalable to genome-wide models [38]. |

| Typical Scale | Genome-scale (thousands of reactions) [40] [38]. | Genome-scale [40] [39]. | Small to medium-scale pathways (dozens to hundreds of reactions) [38]. |

| Omics Data Integration | Transcriptomics can be used to create context-specific models [41]; Integrates with metabolomics for validation via MFA [38]. | Proteomics data can be used to constrain enzyme abundance levels [39]. | Parameters can be informed by multi-omics data; used to interpret time-course transcriptomic/metabolomic data. |

Experimental Protocols for Model Construction and Validation

The application of metabolic models relies on rigorous experimental protocols for their construction, simulation, and, crucially, validation. The following workflows are commonly employed in plant metabolic engineering studies.

Protocol for Constraint-Based Modeling with FBA

This protocol outlines the key steps for developing and using a constraint-based model to predict metabolic fluxes.

- Genome-Scale Model (GEM) Reconstruction: The process begins with the automated or manual assembly of a genome-scale metabolic network from genomic and biochemical databases [40]. This network is represented as a stoichiometric matrix (S), where rows correspond to metabolites and columns to reactions. The GEM includes all known metabolic reactions, their stoichiometry, and gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations.

- Defining Constraints and Objective Function: The system is constrained by defining upper and lower bounds (

vb) for each reaction, typically based on nutrient uptake rates or thermodynamic irreversibility [39]. A biologically relevant objective function is chosen, such as the maximization of biomass production for microbial growth simulations [39]. - Steady-State Flux Prediction with FBA: Under the assumption of steady-state (S · v = 0), linear programming is used to find a flux distribution (

v) that maximizes or minimizes the objective function while satisfying all constraints [39] [38]. The output is a prediction of the flux through every reaction in the network. - Integration of Omics Data for Context-Specificity: To tailor a general GEM to a specific condition (e.g., a plant tissue or stress response), omics data can be integrated. For example, transcriptomic data can be used with algorithms like TIDE (Tasks Inferred from Differential Expression) to infer changes in metabolic pathway activity [41].

- Experimental Validation: Model predictions, such as growth rates or secretion of specific metabolites, must be validated against experimental measurements. For instance, the Chlorella ohadii GEM was validated by comparing its predicted growth rates with actual measurements under three different growth conditions [40].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of Flux Balance Analysis.

Protocol for Advanced Enzyme-Constrained Flux Balance Analysis

For more realistic predictions, the standard FBA approach can be enhanced by incorporating enzyme kinetics, as demonstrated in an iGEM project modeling L-cysteine overproduction in E. coli [39]. This protocol can be adapted for plant systems.

- Base GEM Curation and Refinement: Start with a well-curated GEM. Perform "gap-filling" to add missing reactions known to exist in the organism based on biochemical literature or databases [39].

- Model Modification to Reflect Genetic Engineering: Modify the model to reflect metabolic engineering edits. This includes:

- Application of Enzyme Constraints: Use a computational workflow like ECMpy to integrate enzyme kinetic data. This involves splitting reversible reactions into forward and reverse directions and assigning

Kcatvalues from databases like BRENDA. A total enzyme mass constraint is also applied [39]. - Simulation and Analysis under Physiologically Relevant Conditions: Set the medium conditions in the model to match the experimental bioreactor or growth medium by defining uptake rates for all available nutrients. Perform FBA or related simulations to predict flux distributions and growth [39].

- Validation with Multi-Omics Data: Compare model predictions with experimental results, such as measured export rates of the target metabolite (e.g., L-cysteine) and growth yields. Proteomic data can further validate the assumed enzyme abundances [39].

Table 2: Key Modifications for Modeling an Engineered L-Cysteine Pathway in E. coli [39]

| Parameter | Gene/Enzyme/Reaction | Original Value | Modified Value | Justification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kcat_forward | PGCD (SerA) | 20 1/s | 2000 1/s | Reflects removal of feedback inhibition [40] |

| Kcat_forward | SERAT (CysE) | 38 1/s | 101.46 1/s | Accounts for mutant enzyme with higher activity [2] |

| Gene Abundance | SerA (b2913) | 626 ppm | 5,643,000 ppm | Models increased expression from a strong promoter [39] |

| Gene Abundance | CysE (b3607) | 66.4 ppm | 20,632.5 ppm | Models increased expression from a strong promoter [39] |

Multi-Omics Integration for Model Validation in Plant Systems

Validating metabolic models requires a systems-level approach, where model predictions are confronted with multi-omics data obtained from real plant systems. This integration is key to moving from in silico predictions to confirmed biological insight.

Case Study: Validating a Pan-Genome Scale Model for Green Algae

A seminal study on the ultra-fast-growing alga Chlorella ohadii exemplifies this process [40]. Researchers developed a semi-automated platform for the de novo generation of genome-scale algal metabolic models. The enzyme-constrained model of C. ohadii was used to predict growth rates under three distinct conditions. Crucially, these predictions were validated in parallel experiments where actual growth rates were measured, confirming the model's accuracy. Furthermore, the model was used in comparative flux analyses with existing models of other green algae. This in silico comparison identified potential gene targets for growth improvement not only in standard conditions but also in extreme light environments where C. ohadii excels. This work demonstrates how GEMs, calibrated and validated with experimental data, can uncover the metabolic basis of superior phenotypes and guide engineering strategies [40].

Case Study: Integrating Transcriptomics and Metabolomics to Elucidate Specialized Metabolism

Multi-omics integration is particularly powerful for deciphering the complex regulation of specialized (secondary) metabolism in medicinal plants. Studies on Bidens alba and Panax ginseng provide robust protocols for this [34] [22].

- Tissue-Specific Sampling: Samples are collected from different organs (e.g., flowers, leaves, stems, roots) or at various developmental stages (e.g., fruit maturation stages) to capture spatial and temporal metabolic heterogeneity [34] [22].

- Metabolomic Profiling: Widely targeted metabolomics using UPLC-MS/MS is employed to identify and quantify hundreds to thousands of metabolites, such as flavonoids and terpenoids [34] [22].

- Transcriptome Sequencing: RNA-seq is performed on the same samples to generate a comprehensive profile of gene expression [34] [22].

- Correlation and Co-expression Network Analysis: Advanced bioinformatics, including weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA), are used to correlate the accumulation of specific metabolites with the expression of biosynthetic genes and transcription factors (e.g., MYB, bHLH) [34] [22]. This identifies key regulatory nodes and candidate genes for pathway engineering.

- Model Refinement and Hypothesis Generation: The generated "gene-to-metabolite" association networks provide a quantitative framework that can be used to refine existing kinetic or constraint-based models. The identified key regulators and rate-limiting steps become direct targets for in silico testing of metabolic engineering strategies before wet-lab experimentation.

The following diagram visualizes this multi-omics cycle for model validation and refinement.

Successfully implementing the protocols above requires a suite of key software tools, databases, and experimental reagents.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Resources for Metabolic Modeling and Validation

| Category | Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Software & Tools | COBRApy [39] | A Python package for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA) of metabolic models, used for performing FBA. |

| ECMpy [39] | A workflow for constructing enzyme-constrained metabolic models to improve flux prediction accuracy. | |

| MTEApy [41] | An open-source Python package for inferring metabolic pathway activity from transcriptomic data using the TIDE algorithm. | |

| Databases | BRENDA [39] | A comprehensive enzyme database providing kinetic parameters (e.g., Kcat) essential for enzyme-constrained modeling. |

| KEGG [34] [22] | A database resource for understanding high-level functions of the biological system, used for pathway annotation and enrichment analysis of omics data. | |

| PlantTFDB [34] | A database for identifying transcription factors and their binding sites in plants, crucial for multi-omics regulatory network analysis. | |

| Experimental Reagents | SM1/LB Medium [39] | A defined growth medium used in bioreactor experiments; its composition is used to set metabolite uptake constraints in the model. |

| TRIzol Reagent [22] | A ready-to-use reagent for the isolation of high-quality total RNA from cells and tissues for transcriptomic sequencing. | |

| 13C-labeled substrates [38] | Isotopically labeled metabolites (e.g., 13CO2) used in Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) to experimentally measure intracellular metabolic fluxes. |

Constraint-based (FBA/GEM) and kinetic modeling approaches offer complementary strengths for predicting metabolic fluxes in plant systems. FBA excels in providing genome-scale, stoichiometry-driven predictions of steady-state fluxes, especially when enhanced with enzyme constraints. Kinetic modeling, though limited in scale, provides unparalleled insight into dynamic and regulatory behaviors. The critical factor for the successful application of either approach in plant metabolic engineering is their rigorous validation through a multi-omics cycle. By integrating transcriptomic, metabolomic, and proteomic data, researchers can refine models, generate testable hypotheses, and confidently identify metabolic engineering targets. This model-driven, omics-validated framework is poised to significantly accelerate the development of plants with enhanced nutritional, medicinal, and agronomic traits.

The validation of outcomes in plant metabolic engineering is a complex endeavor, crucial for developing crops with enhanced nutritional value, stress resilience, and sustainable yields. The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) with multi-omics research is revolutionizing this field, transforming traditional, labor-intensive processes into streamlined, predictive, and highly accurate workflows. This guide compares the performance of various AI-driven approaches and the experimental protocols that underpin the discovery and validation of plant metabolic pathways.

The Multi-Omics and AI Workflow for Pathway Validation

A typical workflow for validating plant metabolic engineering outcomes leverages AI to integrate data from various molecular layers. The diagram below outlines this multi-stage process.

Figure 1: A high-level workflow for AI-driven discovery and validation of plant metabolic pathways. Multi-omics data is integrated computationally to generate predictive models, which are then tested through experimental validation.

Core AI Integration Strategies for Multi-Omics Data

The effectiveness of an AI-driven discovery pipeline heavily depends on the strategy used to integrate data from different omics layers. The following diagram illustrates the primary integration methods.

Figure 2: Primary strategies for integrating multi-omics data within an AI/ML framework, each with distinct advantages for different analytical goals [42].

Comparative Analysis of AI-Driven Platform Methodologies

The table below summarizes the core technical approaches and performance metrics of leading AI platforms relevant to biological pathway discovery.

Table 1: Comparison of AI Platform Approaches for Biological Discovery

| Platform / Method | Core AI Methodology | Reported Efficiency Gains | Key Strengths | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exscientia Centaur AI [43] | Generative AI, Deep Learning | ~70% faster design cycles; 10x fewer compounds synthesized [43] | End-to-end platform; Integrates patient-derived biology [43] | Small-molecule drug design, Oncology [43] |

| Insilico Medicine Pharma.AI [43] | Generative AI, Reinforcement Learning | Target to Phase I in 18 months (reported instance) [43] | Comprehensive suite (target ID to clinical prediction) [43] | End-to-end drug discovery, Multi-omics data integration [43] |

| Graph Machine Learning [44] | Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Superior pattern recognition in complex, relational data [44] | Models biological knowledge networks; Handles heterogeneous data [44] | Biomarker discovery, Multi-omics integration, Network biology [44] |

| Intermediate Integration [42] | Joint matrix decomposition, Variational Autoencoders | Mitigates "curse of dimensionality" from early integration [45] | Processes features based on redundancy/complementarity across omics [42] | Exploratory analysis, Identifying latent data factors [45] |

| Late Integration [45] [42] | Ensemble models (Averaging, Voting) | Robust performance by leveraging best-performing omic model [45] | Reduces model complexity; Allows for different algorithms per omic [42] | Predictive modeling when one omic type is highly informative [45] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Pathway Validation

Protocol 1: ML-Driven Identification of Metabolic Engineering Targets from Multi-Omics Data

This protocol uses intermediate integration to discover key regulatory nodes in a plant metabolic network.

- Sample Preparation: Collect plant tissue (e.g., leaf, root) from wild-type and genetically engineered plants under controlled and stress conditions (e.g., drought, pathogen attack). Use a minimum of 5 biological replicates per group [11].

- Multi-Omics Data Generation:

- Genomics: Use whole-genome sequencing to identify genetic variations and engineered constructs.

- Transcriptomics: Perform RNA-Seq to profile genome-wide gene expression levels.

- Metabolomics: Employ LC-MS/MS (Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry) for untargeted profiling of primary and secondary metabolites [11].

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize raw data, handle missing values using k-nearest neighbors (KNN) imputation, and perform log-transformation where appropriate to stabilize variance.

- Intermediate Data Integration: Process the normalized multi-omics matrices using a Variational Autoencoder (VAE). The VAE learns a compressed, joint latent representation (e.g., 50 dimensions) that captures the essential biological variance across all omics layers [45].

- Supervised ML for Target Identification: Input the latent representation from the VAE into a Random Forest classifier or regressor to predict the levels of high-value target metabolites (e.g., a specific alkaloid or flavonoid). Rank all features in the latent space by their importance in the Random Forest model.

- Validation: Select the top-ranked genes/proteins for functional validation using CRISPR-Cas9 or RNAi in a model plant, followed by metabolite analysis to confirm the predicted changes in the target metabolic pathway [46].

Protocol 2: Graph-Based Validation of Predicted Metabolic Pathways

This protocol uses graph machine learning to place ML-discovered targets into a known biological context for systems-level validation.

- Heterogeneous Knowledge Graph Construction:

- Nodes: Define entities such as Genes (from transcriptomics), Proteins (from proteomics), Metabolites (from metabolomics), and Phenotypes [44].

- Edges: Define relationships between nodes using prior knowledge from databases (e.g., protein-protein interactions, enzyme-substrate relationships in KEGG, gene-regulatory interactions).

- Node Features: Populate features using the experimental multi-omics data (e.g., gene expression level, metabolite abundance) as attributes to the corresponding nodes [44].

- Model Training with Graph Neural Networks (GNNs):

- Use a message-passing GNN architecture. In each layer, nodes aggregate information from their neighbors to update their own representation.

- Train the model in a supervised manner to predict a property, such as the presence of a metabolic pathway or the accumulation of a key metabolite [44].

- Model Interpretation and Pathway Hypothesis:

- Analyze the GNN's predictions using explainable AI (XAI) techniques to identify which nodes and edges in the graph were most influential.

- This analysis generates a testable hypothesis for a complete metabolic pathway, including key regulators and rate-limiting steps that were not apparent from the omics data alone [44].

- Experimental Cross-Validation: Validate the graph-derived hypothesis by engineering plants to perturb the key "bridge" nodes identified by the GNN and measure the resulting impact on the entire metabolic network using targeted metabolomics [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AI-Driven Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Application in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS Systems [11] | High-sensitivity identification and quantification of small-molecule metabolites. | Generating high-quality metabolomics data for model training and experimental validation. |

| Multi-Omics Data Integration Suites (e.g., tools in PyTorch Geometric, Deep Graph Library) [44] | Software libraries providing pre-built algorithms for integration and graph-based learning. | Implementing intermediate integration (VAEs) and constructing GNNs for knowledge graph analysis. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing Kits | Precise manipulation of plant genomes to knock out or overexpress candidate genes. | Functionally validating AI-predicted gene targets in a plant model system. |

| High-Throughput Phenotyping Platforms [47] | Automated, non-invasive measurement of plant growth, physiology, and morphology. | Linking validated metabolic changes to observable plant traits and fitness outcomes. |

| Curated Biological Knowledge Bases (e.g., KEGG, PlantConnectome) [48] | Structured databases of known molecular interactions, pathways, and gene functions. | Providing the foundational prior knowledge for constructing heterogeneous graphs for GNN analysis. |

The integration of AI and ML into plant metabolic engineering is no longer a speculative future but a present-day reality that dramatically accelerates pathway discovery and validation. As demonstrated, different AI strategies—from the generative chemistry of platforms like Insilico Medicine to the relational power of Graph Neural Networks—offer complementary strengths. The choice of strategy depends on the specific research goal, whether it is the de novo design of a metabolic sink or the systems-level understanding of an existing pathway. The continued development of robust experimental protocols and specialized reagents will further solidify this synergy, paving the way for a new era of predictive and precise plant metabolic engineering.

In plant metabolic engineering, predicting the outcome of genetic modifications remains a significant challenge due to the complex, multi-layered nature of biological systems. The integration of genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data—collectively termed multi-omics—onto shared biochemical networks provides a powerful framework to overcome this hurdle. This approach moves beyond single-layer analysis to create holistic models of plant physiology, enabling researchers to systematically validate metabolic engineering outcomes, identify key regulatory nodes, and uncover non-intuitive interactions within the metabolic network. By mapping various molecular data types onto a unified network context, scientists can transition from correlative observations to mechanistic, predictive models of plant behavior, thereby de-risking the engineering pipeline and accelerating the development of improved crop varieties and plant-based bioproducts.

Comparative Analysis of Multi-Omics Network Integration Methodologies

Various computational strategies have been developed for integrating multi-omics data into networks, each with distinct strengths, experimental requirements, and performance outcomes. The table below provides a structured comparison of the predominant methodologies used in plant research.

Table 1: Performance and Application Comparison of Multi-Omics Network Integration Methods

| Methodology | Core Principle | Best-Suited Data Types | Key Performance Metrics | Experimental Validation Success |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network-Based Longitudinal Integration (netOmics) | Uses hybrid networks (inferred + known relationships) and random walks to analyze temporal data [49]. | Longitudinal transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics [49]. | Identifies dynamic, multi-layer interactions and kinetic patterns missed by single-omics analysis [49]. | Successfully revealed novel biological mechanisms and functional modules in case studies [49]. |

| Machine Learning with Single-Omics Models | Builds independent prediction models (e.g., rrBLUP, Random Forest) for each omics layer [50]. | Genomic (G), Transcriptomic (T), Methylomic (M) data [50]. | Achieved comparable prediction accuracy for Arabidopsis traits (e.g., flowering time) across G, T, and M models [50]. | Validated 9 novel genes regulating flowering time in Arabidopsis, demonstrating accession-dependent gene contributions [50]. |

| Consensus Multi-Omics Clustering (MOVICS) | Integrates multiple clustering algorithms to define robust molecular subtypes from multi-omics data [51]. | mRNA, lncRNA, miRNA, DNA methylation, somatic mutations [51]. | Established prognostic subtypes for Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OSCC); superior performance to existing models [51]. | Identified CA9 as a therapeutic target; in vitro knockdown inhibited cancer cell proliferation and migration [51]. |

| Constraint-Based Metabolic Modeling (CBM) | Uses biochemical network stoichiometry and constraints (e.g., enzyme capacity) to predict metabolic fluxes [18]. | Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs), transcriptomics, proteomics [18]. | Successfully applied to optimize biofuel precursor production and identify targets for enhancing crop yield and stress tolerance [18]. | Guided metabolic engineering in microbes; applied to study phytochemical biosynthesis pathways in plants [18]. |

Key Insights from Comparative Performance

- Complementarity of Omics Layers: Different omics data types can achieve similar predictive accuracy for complex traits but often identify distinct sets of key genes or features. For example, in predicting Arabidopsis flowering time, models based on genomics, transcriptomics, and methylomics showed comparable performance but limited overlap in the important genes they identified, suggesting they capture complementary biological information [50].

- Integration Enhances Predictive Power: Models that integrate multiple omics layers consistently outperform single-omics models. In plant studies, integrated models not only provided the best prediction accuracy but also revealed known and novel gene interactions, extending knowledge of existing regulatory networks [50].

- Temporal Dynamics are Crucial: Methods that incorporate time-series data, such as longitudinal integration, are uniquely powerful for uncovering the dynamic sequence of regulatory events and causal relationships across omics layers, which are essential for understanding developmental processes and stress responses [49].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol for Network-Based Longitudinal Integration with netOmics

The netOmics pipeline is designed for multi-omics time-course data to infer dynamic network relationships [49].

Step 1: Data Pre-processing

- Filtering and Normalization: Raw count data from each omics block (e.g., RNA, proteins) are filtered to remove low counts and normalized using platform-specific methods. A filter is applied to retain molecules with the highest expression fold change across the time course [49].

- Handling Longitudinal Design: The method accommodates non-matching timepoints between omics blocks and uneven designs through a subsequent modeling step [49].

Step 2: Modeling and Clustering Time Profiles

- Linear Mixed Model Splines: A Linear Mixed Model Spline framework models each molecule's expression over time, accounting for inter-individual variation and allowing interpolation of missing timepoints [49].

- Multi-Block Clustering: Modeled expression profiles are clustered into groups with similar kinetic behaviors using multivariate methods like multi-block Projection on Latent Structures (block PLS). The optimal number of clusters is determined by maximizing the average silhouette coefficient [49].

Step 3: Hybrid Network Reconstruction

- Data-Driven Inference: For gene expression data, algorithms like ARACNe are used to infer transcription factor-target gene interactions by estimating mutual information from expression profiles [49].

- Knowledge-Driven Integration: Experimentally determined interactions are incorporated from databases:

- Cluster-Specific Subnetworks: Separate networks are built for each kinetic cluster identified in Step 2, in addition to a global network [49].

Step 4: Network Exploration and Interpretation

- Random Walk Algorithm: A state-of-the-art propagation algorithm is used to explore the hybrid network. Starting from known associations (e.g., a phenotype), the algorithm iteratively propagates a signal through the network to identify new candidate nodes (e.g., genes, metabolites) based on their proximity to the starting set [49].

- Functional Analysis: Resultant modules and key nodes are subjected to over-representation analysis to uncover enriched biological functions [49].

Protocol for Multi-Omics Prediction Model Interpretation