From Roots to Remedies: Modern Strategies for Discovering Bioactive Compounds in Plants

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the modern landscape of plant bioactive compound discovery, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

From Roots to Remedies: Modern Strategies for Discovering Bioactive Compounds in Plants

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the modern landscape of plant bioactive compound discovery, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational knowledge of major phytochemical classes and their historical significance in medicine. The scope extends to contemporary extraction and screening methodologies, including advanced mass spectrometry and bioinformatics. The article also addresses key challenges such as compound rediscovery and optimization, and critically examines the validation of biological activities and the comparative advantages of natural products over synthetic libraries in drug discovery. Finally, it synthesizes future directions, emphasizing the convergence of traditional knowledge with cutting-edge technology to overcome antimicrobial resistance and other global health challenges.

The Phytochemical Universe: Exploring Plant Bioactive Diversity and Historical Legacy

Bioactive compounds in plants are organic molecules capable of eliciting physiological responses in living organisms, forming the cornerstone of numerous therapeutic interventions and nutraceutical applications. These compounds originate from the sophisticated interplay between primary and specialized metabolism, creating a vast chemical landscape that researchers explore for drug discovery and development [1]. For pharmaceutical scientists and natural product researchers, understanding this metabolic continuum is fundamental to unlocking novel bioactive entities with potential applications against diverse pathologies including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and infectious diseases [2].

Plant metabolism is strategically divided into primary (central) metabolism, encompassing reactions absolutely vital for survival, and secondary (specialized) metabolism, which fulfills multifaceted functions in plant-environment interactions [1]. While primary metabolites are highly conserved across species, specialized metabolites demonstrate remarkable diversity at species, organ, tissue, and developmental levels, contributing to their vast pharmacological potential [1]. The evolution of specialized metabolism occurred primarily through enzyme recruitment from primary metabolic pathways following gene duplication events, resulting in the tremendous structural variety observed in plant-derived bioactive compounds today [1].

Primary Metabolism: The Biochemical Core

Fundamental Concepts and Components

Primary metabolites represent the essential biochemical machinery required for plant growth, development, and reproduction [3]. These compounds are universally present in all plant species and are produced during the active growth phase (trophophase) as direct products of fundamental metabolic pathways including glycolysis, the Krebs cycle, and the Calvin cycle [4] [3]. Unlike their specialized counterparts, the absence of primary metabolites would result in immediate physiological consequences, ultimately proving fatal to the organism [3].

Table 1: Core Primary Metabolites and Their Principal Functions

| Metabolite Category | Representative Examples | Primary Physiological Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrates | Glucose, sucrose, starch, cellulose | Energy storage, structural components (cell walls), metabolic intermediates |

| Proteins & Enzymes | Rubisco, dehydrogenases, proteases | Catalyzing metabolic reactions, structural support, cellular signaling |

| Lipids | Phospholipids, triglycerides | Membrane structural components, energy storage, signaling molecules |

| Organic Acids | Citric acid, malic acid | Intermediate compounds in TCA cycle, pH regulation |

| Nucleic Acids | DNA, RNA | Genetic information storage and transfer |

Primary Metabolic Pathways as Precursor Pools

The paramount significance of primary metabolism in bioactive compound research lies in its role as a generator of precursor molecules for specialized metabolism. Key primary metabolic pathways provide the essential building blocks and energy required for synthesizing secondary metabolites [1]. The shikimate pathway yields the aromatic amino acids phenylalanine and tyrosine, which serve as precursors for numerous phenolic compounds [1]. Similarly, glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle provide carbon skeletons and energy, while acetyl-CoA serves as the foundational unit for terpenoid biosynthesis [4]. This metabolic interconnectivity establishes primary metabolism as the indispensable foundation upon which specialized bioactive compounds are constructed.

Specialized Secondary Metabolites: Nature's Bioactive Arsenal

Defining Characteristics and Ecological Significance

Secondary metabolites, also termed specialized metabolites, are organic compounds not directly involved in the normal growth, development, or reproduction of an organism [3]. These metabolites are typically produced during the stationary phase (idiophase) and are characterized by their species-specific distribution and diverse ecological functions [3]. From a pharmacological perspective, these compounds represent nature's most sophisticated bioactive arsenal, evolved over millennia to mediate complex ecological interactions including plant defense, pollinator attraction, and interspecies competition [1] [4].

Specialized metabolites differ fundamentally from primary metabolites in their restricted distribution across the plant kingdom, often being unique to specific plant families, genera, or even species [4]. While not essential for basic metabolic processes, these compounds significantly enhance plant survival and fitness in specific ecological contexts, with an estimated 20% of flowering plants producing biologically active alkaloids as part of their defense strategy [4].

Major Classes of Bioactive Secondary Metabolites

Secondary metabolites with documented bioactivities are broadly categorized into three major classes based on their chemical structure and biosynthetic origin.

Phenolic Compounds

Phenolic compounds constitute a large and heterogeneous group of secondary metabolites characterized by the presence of one or more aromatic rings bearing hydroxyl functional groups [4]. These compounds are predominantly synthesized through the shikimate and phenylpropanoid pathways, with phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL) serving as the gateway enzyme that directs carbon flow from primary to secondary metabolism [1]. Phenolic compounds contribute significantly to plant defense against biotic and abiotic stresses while also serving as key determinants of fruit pigmentation and nutritional quality [1].

Phenolics encompass several subclasses including simple phenolics, flavonoids, tannins, and lignin. Tannins are further divided into condensed tannins (proanthocyanidins) and hydrolysable tannins (gallotannins and ellagitannins) [1]. Epidemiological studies suggest that high dietary intake of polyphenols is associated with decreased risk of cardiovascular diseases and cancer, attributed to their potent antioxidant and antiproliferative properties [1]. From a drug discovery perspective, phenolic compounds offer tremendous potential as antioxidant, antimicrobial, antiviral, and antitumor agents [1].

Terpenoids/Isoprenoids

Terpenoids represent the most extensive and structurally diverse class of secondary metabolites, with over 40,000 structures identified to date [4]. These compounds are classified based on the number of five-carbon isoprenoid units they contain: monoterpenes (2 units), sesquiterpenes (3 units), diterpenes (4 units), triterpenes (6 units), and tetraterpenes (8 units) [4]. Terpenoid biosynthesis occurs primarily through the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) and mevalonic acid (MVA) pathways, both originating from primary metabolic precursors [4].

Pharmacologically significant terpenoids include the antimalarial compound artemisinin (a sesquiterpene), the anticancer drug paclitaxel (a diterpene), and essential oil components like menthol (a monoterpene) with documented insect-repellent qualities [4]. The pyrethroids, monoterpene esters from chrysanthemum species, are commercially utilized as biodegradable insecticides with low mammalian toxicity [4].

Nitrogen-Containing Compounds

This category encompasses alkaloids and glucosinolates, characterized by the presence of nitrogen atoms in their chemical structures. Alkaloids constitute a large group of nitrogen-containing compounds typically derived from amino acid precursors such as tryptophan, tyrosine, or lysine [4]. These compounds often demonstrate pronounced physiological effects in mammals and include medicinally indispensable agents such as morphine and codeine (analgesics) from the opium poppy, vincristine and vinblastine (antimitotic agents) from the periwinkle plant, and quinine (antimalarial) from cinchona bark [4].

Alkaloids frequently act as potent neurotoxins, enzyme inhibitors, or membrane transport inhibitors in ecological contexts, serving as effective herbivore deterrents [4]. The structural complexity of alkaloids presents both challenges and opportunities for pharmaceutical development, with many serving as template molecules for semi-synthetic derivatives with optimized pharmacological profiles.

Table 2: Major Classes of Bioactive Secondary Metabolites and Their Applications

| Metabolite Class | Biosynthetic Origin | Bioactive Examples | Documented Pharmacological Activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenolic Compounds | Shikimate/Phenylpropanoid pathways | Flavonoids, tannins, lignins | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, cardioprotective, anticancer [1] [5] |

| Terpenoids | Mevalonate/MEP pathways | Artemisinin, paclitaxel, menthol | Antimalarial, anticancer, insect-repellent, aroma therapy [4] |

| Alkaloids | Amino acid precursors | Morphine, vinblastine, quinine, caffeine | Analgesic, antimitotic, antimalarial, stimulant [4] |

| Nitrogen/Sulfur-Containing | Amino acid derivatives | Glucosinolates, allyl sulfides | Antimicrobial, chemopreventive, detoxification support [1] |

Analytical Framework: From Metabolic Pathways to Quantitative Bioactivity Assessment

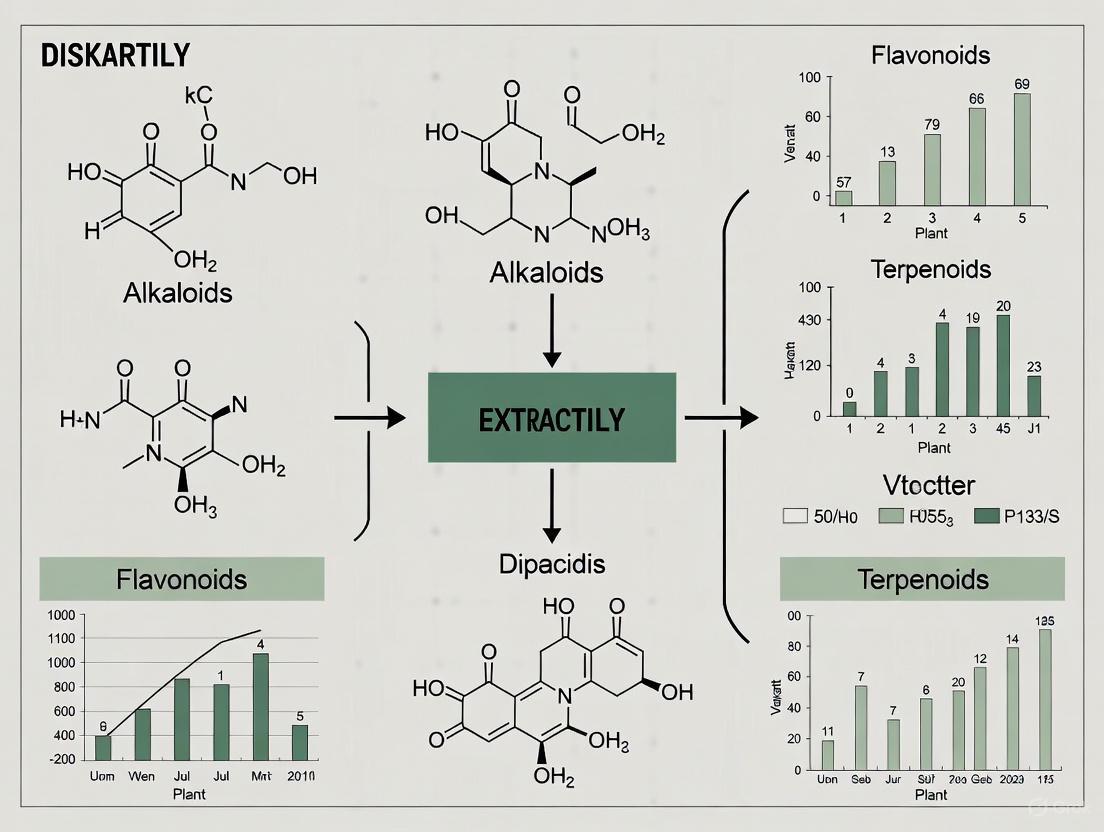

The Metabolic Pathway from Primary to Specialized Metabolism

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected relationship between primary metabolic pathways and the biosynthesis of major classes of bioactive secondary metabolites:

Bioactivity-Guided Fractionation Workflow

The standard approach for discovering bioactive compounds from plant material follows a systematic bioactivity-guided fractionation protocol, as detailed below:

Quantitative Bioactivity Assessment: The EDV50 Approach

In natural product chemistry, bioactivity potency has traditionally been expressed as half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) or inhibitory concentration (IC50). However, the counterintuitive nature of this system (where lower values indicate higher potency) has led to the development of the EDV50 (half-maximal effective dilution volume) parameter, defined as the reciprocal of EC50 (1/EC50) [6]. This quantitative approach enables more intuitive assessment of bioactive compounds, as higher EDV50 values correspond directly to increased potency [6].

The total bioactivity contained within a plant extract can be calculated using the following formula, which incorporates both yield and potency parameters:

Total Bioactivity = Weight of Extract × EDV50

This quantitative framework allows researchers to track bioactivity through successive purification steps, determining whether losses in total activity result from material loss, compound degradation, or disruption of synergistic interactions between compounds [6]. For example, in studies of Backhousia myrtifolia (Grey Myrtle), this approach demonstrated that despite substantial material loss during HPLC purification, the total anti-inflammatory bioactivity was retained across all purified fractions, indicating additive rather than synergistic interactions [6].

Advanced Methodologies in Bioactive Compound Research

Extraction Techniques and Technological Advances

Efficient extraction of bioactive compounds from plant material represents a critical initial step in natural product research. Traditional methods including maceration, percolation, and Soxhlet extraction have been progressively supplemented with advanced techniques that offer improved efficiency, reduced solvent consumption, and enhanced sustainability profiles [7].

Modern extraction methodologies include supercritical fluid extraction (SFE), microwave-assisted extraction (MAE), ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE), instant controlled pressure drop (DIC), pressurized liquid extraction (PLE), and negative pressure cavitation (NPC) [7]. These innovative approaches have demonstrated significant advantages in terms of extraction yields, operational efficiency, and preservation of thermolabile bioactive compounds, making them increasingly indispensable in natural product research and development.

The Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies for Bioactive Compound Investigation

| Reagent/Methodology | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Extraction Solvents (ethanol, methanol, ethyl acetate, hexane, water) | Sequential extraction based on polarity for comprehensive metabolite recovery [8] | Solvent selectivity determines extract composition; ethanol shows slightly better retention of total bioactivity vs. sequential extracts [6] |

| Chromatographic Media (HPLC columns, TLC plates, solid-phase extraction cartridges) | Separation and purification of individual compounds from complex mixtures | HPLC purification may cause material loss but often retains total bioactivity through concentration of active principles [6] |

| Bioassay Systems (cell-based assays, enzyme inhibition tests, antimicrobial susceptibility) | Assessment of biological activity and therapeutic potential | Anti-inflammatory screening commonly uses COX/LOX inhibition; anticancer employs cell proliferation assays; antimicrobial uses dilution methods [6] [2] |

| Analytical Standards (reference compounds for quantification) | Calibration and validation of analytical methods | Essential for accurate quantification of specific metabolite classes (e.g., gallic acid equivalents for phenolics) [8] |

| Spectroscopic Instruments (NMR, HR-MS, LC-MS/MS) | Structural elucidation and compound identification | NMR provides definitive structural information; HR-MS enables precise molecular formula determination [6] [5] |

The systematic investigation of bioactive compounds from their origins in primary metabolism to their final manifestation as specialized secondary metabolites represents a foundational strategy in drug discovery and development. The intricate relationship between these metabolic domains underscores the importance of understanding biosynthetic pathways when seeking to optimize the production, isolation, and application of plant-derived therapeutics.

Advanced technologies including omics platforms, bioactivity-guided fractionation, and quantitative bioactivity assessment are transforming natural product research, enabling more efficient discovery and characterization of novel bioactive entities [9] [6]. Concurrently, innovations in extraction methodologies and formulation approaches, particularly nanotechnology-based delivery systems, are addressing historical challenges associated with the bioavailability and stability of plant-derived compounds [9] [7].

For researchers and drug development professionals, integrating this multidisciplinary knowledge—from fundamental metabolic principles to advanced analytical techniques—provides a powerful framework for unlocking the full potential of plant bioactive compounds in addressing contemporary therapeutic challenges.

Plant bioactives, or secondary metabolites, are organic compounds produced by plants that are not essential for primary growth and development but play crucial roles in defense, communication, and adaptation. These compounds represent a vast reservoir of chemical diversity with significant implications for human health, serving as lead compounds for pharmaceutical development, nutraceuticals, and agrochemicals. Within the broader context of bioactive compound discovery research, understanding the structural diversity, biosynthetic origins, and biological activities of these major classes is fundamental. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of four principal classes of plant bioactives—terpenoids, phenolics, alkaloids, and glucosinolates—framed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. The content integrates current research trends, classification systems, pharmacological potential, and advanced analytical methodologies driving this field forward.

Terpenoids

Structural Diversity and Classification

Terpenoids, also known as isoprenoids, constitute one of the largest and most structurally diverse families of natural products, with over 40,000 identified compounds [10] [11]. Their basic structural unit is the five-carbon isoprene molecule (C5H8). Terpenoids are classified based on the number of isoprene units they contain, which also correlates with their carbon skeleton size and functional complexity [12] [10]. While sometimes used interchangeably with "terpenes," terpenoids are distinguished by the presence of additional functional groups, typically containing oxygen, which often enhances their biological activity [10].

Table 1: Classification of Major Terpenoids Based on Isoprene Units

| Class | Isoprene Units | Carbon Atoms | Example Compounds | Biological Sources | Notable Pharmacological Activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monoterpenoids | 2 | C10 | Menthol, Limonene, Camphor | Mentha spp., Citrus peels, Cinnamomum camphora | Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, Pollinator Attraction [10] [11] |

| Sesquiterpenoids | 3 | C15 | Artemisinin, Farnesol | Artemisia annua, Various flowers | Antimalarial, Antimicrobial [11] |

| Diterpenoids | 4 | C20 | Taxol, Ginkgolide | Pacific Yew (Taxus), Ginkgo biloba | Anticancer, Neuroprotective [10] [11] |

| Triterpenoids | 6 | C30 | Saponins, Steroids | Ginseng, Glycyrrhiza glabra | Membrane stabilization, Anti-inflammatory [10] [11] |

| Tetraterpenoids | 8 | C40 | Lycopene, Beta-Carotene | Tomatoes, Carrots | Antioxidant, Provitamin A [10] [11] |

| Polyterpenoids | >8 | >C40 | Rubber | Hevea brasiliensis | Industrial applications [10] |

Biosynthesis and Ecological Roles

Terpenoid biosynthesis occurs via two primary pathways: the mevalonate (MVA) pathway in the cytosol and the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway in the plastids [11]. The MVA pathway primarily produces sesquiterpenes (C15) and triterpenes (C30), while the MEP pathway is responsible for monoterpenes (C10), diterpenes (C20), and tetraterpenes (C40) [11]. Key enzymatic steps, particularly those catalyzed by terpene synthases (TPS), generate immense structural diversity through cyclization and subsequent modifications such as oxidation, reduction, and glycosylation [11].

Ecologically, terpenoids are critical for plant survival. They function as direct defense compounds through insecticidal (e.g., limonene, resin acids) and antifungal actions (e.g., farnesene) [11]. They also serve as volatile signals for pollinator attraction and as cues to attract natural enemies of herbivores [10] [11]. The pharmacological significance of terpenoids is profound, with applications ranging from the antimalarial drug artemisinin to the anticancer agent paclitaxel (Taxol) [10] [11].

Diagram 1: Terpenoid Biosynthesis Pathways

Phenolics

Chemical Characterization and Bioactivities

Phenolic compounds are characterized by the presence of at least one aromatic ring bearing one or more hydroxyl groups. They are ubiquitous in plants and represent a large family of over 8,000 structures. A primary classification divides them into hydroxybenzoic acids (e.g., gallic acid, protocatechuic acid) and hydroxycinnamic acids (e.g., caffeic acid, ferulic acid, p-coumaric acid) based on their carbon skeleton [13]. More complex structures include flavonoids, stilbenes, and lignans. In plants, they can exist in free form or as conjugated derivatives with sugars, organic acids, or other compounds [13].

Phenolics exhibit a broad spectrum of bioactivities, including potent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antimicrobial, and neuroprotective effects [14] [13]. They also modulate energy metabolism, influencing lipid and carbohydrate metabolism to help maintain metabolic homeostasis [13]. However, a significant challenge in their application is their relatively low absorption rate and bioavailability, as they are not easily absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract and are prone to degradation and metabolic inactivation [13].

Biotransformation for Enhanced Bioavailability

Biotransformation technology has emerged as a key strategy to overcome the limitations of native phenolic acids. This approach uses enzymatic or microbial methods to directionally modify phenolic acid structures, creating derivatives with higher bioactivity and bioavailability [13]. Key enzymatic pathways include:

- Decarboxylation: Removal of carboxylic acid groups, e.g., conversion of ferulic acid to 4-vinyl guaiacol.

- Reduction: Transformation of specific functional groups to more bioavailable forms.

- Hydrolysis: Cleavage of glycosidic or ester bonds to release active aglycones [13].

Enzymatic methods are favored in food and pharmaceutical applications due to their high substrate specificity, mild reaction conditions, and compliance with food-grade production standards [13]. Key enzymes involved include phenolic acid decarboxylase, phenolic acid esterase, phenolic acid reductase, and β-glucosidase [13]. Advanced techniques like enzyme immobilization are being employed to improve enzymatic stability and reusability for industrial-scale applications [13].

Table 2: Key Enzymes in Phenolic Acid Biotransformation

| Enzyme | Catalytic Function | Reaction Example | Application Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenolic Acid Decarboxylase (PAD) | Catalyzes decarboxylation of hydroxycinnamic acids. | Ferulic acid → 4-Vinyl guaiacol | Generates volatile compounds with enhanced antimicrobial activity [13]. |

| Phenolic Acid Esterase | Hydrolyzes ester bonds in phenolic acid conjugates. | Chlorogenic acid → Caffeic Acid + Quinic Acid | Releases bioactive aglycones, improving absorption [13]. |

| β-Glucosidase | Cleaves β-glycosidic bonds in phenolic glycosides. | Polydatin → Resveratrol | Converts glycosides to more lipophilic and absorbable aglycones [13]. |

| Phenolic Acid Reductase | Reduces specific functional groups on phenolic rings. | Ferulic acid → Dihydroferulic acid | Produces hydrogenated metabolites with potential altered bioactivity [13]. |

Alkaloids

Definition, Distribution, and Pharmacological Significance

Alkaloids are a class of naturally occurring organic compounds characterized by their nitrogen-containing bases, typically derived from amino acids [15]. Their name, meaning "alkali-like," reflects their basic nature due to the presence of one or more nitrogen atoms, often incorporated into heterocyclic ring systems [15]. Alkaloid names conventionally end with the suffix "-ine" [15]. It is estimated that up to one-quarter of higher plant species contain alkaloids, with certain families like Papaveraceae (poppy), Solanaceae (nightshade), and Ranunculaceae (buttercups) being particularly rich sources [15].

The pharmacological effects of alkaloids are diverse and profound. Well-known examples include the potent analgesic morphine, the antimalarial quinine, the respiratory stimulant lobeline, and the chemotherapeutic agents vincristine and vinblastine [15]. It is estimated that alkaloids constitute the basis for over 30% of clinically used drugs, underscoring their immense importance in drug discovery [16]. Their biological activity in plants is often linked to defense against herbivores and pathogens [16].

Modern Discovery and Analytical Techniques

Modern alkaloid research employs sophisticated multi-omics approaches to discover new compounds and elucidate their biosynthetic pathways. A recent study on Murraya species (2025) exemplifies this integrated methodology [16].

Experimental Protocol: Integrated Multi-Omics Analysis of Alkaloids [16]

Plant Material Preparation: Leaves from three Murraya species (M. exotica, M. kwangsiensis, M. tetramera) were harvested, immediately flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and vacuum freeze-dried. The tissue was homogenized with a pre-cooled extraction solvent (methanol:acetonitrile:water = 1:2:1, v/v/v) using mechanical disruption.

Metabolite Profiling via UPLC-ESI-MS/MS:

- Chromatography: A Waters HSS-T3 column (1.8 µm, 2.1 × 100 mm) was used. The mobile phase consisted of solvent A (0.1% formic acid, 5 mM ammonium acetate in water) and solvent B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile), with a gradient elution over 20 minutes.

- Mass Spectrometry: Analysis was performed on a QTRAP 6500+ system with Electrospray Ionization (ESI). Ion spray voltages were ±5,500 V. Data acquisition was conducted in Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) mode.

- Data Analysis: Metabolites were identified by matching spectra against an in-house database. Differential metabolites were screened using criteria of |fold change| ≥ 1.0, VIP (Variable Importance in Projection) ≥ 1, and a p-value < 0.05.

Transcriptomic Sequencing: Total RNA was extracted from leaf tissues. Following quality control (RIN ≥ 8.0), RNA sequencing libraries were constructed and sequenced to elucidate gene expression related to alkaloid biosynthesis.

Network Pharmacology and Molecular Docking: Potential targets of identified bioactive alkaloids were predicted and mapped onto protein-protein interaction networks. Molecular docking simulations (e.g., for tombozine, aegeline) were performed to evaluate binding affinities to core targets like PIK3CA and MAPK8, suggesting potential antitumor mechanisms [16].

This workflow led to the identification of 77 alkaloids from 18 structural classes in Murraya species and linked differential accumulation to species-specific gene expression [16].

Diagram 2: Multi-Omics Workflow for Alkaloid Discovery

Glucosinolates

Structure, Activation, and Health Benefits

Glucosinolates are nitrogen- and sulfur-containing secondary metabolites characteristic of the Brassicaceae family (e.g., broccoli, cabbage, mustard) [17] [18]. Their core structure consists of a β-thioglucoside-N-hydroxy sulfate moiety and a variable side chain derived from amino acids, which classifies them as aliphatic, aromatic, or indole glucosinolates [18].

Intact glucosinolates are biologically inert. Their activity is triggered upon tissue damage (e.g., chewing) which brings them into contact with the enzyme myrosinase (a β-thioglucosidase), leading to a "mustard oil bomb" response [17] [18]. This hydrolysis produces a variety of bioactive derivatives, most notably isothiocyanates (ITCs) like sulforaphane, as well as nitriles, thiocyanates, and epithionitriles [18]. These hydrolysis products are responsible for the health-promoting properties of cruciferous vegetables, which include:

- Cancer chemoprevention through modulation of xenobiotic metabolism, induction of apoptosis, and inhibition of angiogenesis and metastasis [18].

- Anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial activities (e.g., against Helicobacter pylori) [18].

- Cardioprotective and neuroprotective benefits [18].

Strategies for Preparing Bioactive Derivatives

The preparation of glucosinolate derivatives for research and application is primarily achieved through chemical synthesis or enzymatic hydrolysis. Chemical synthesis, while allowing control over reaction conditions, often involves hazardous reagents and results in low yields [18]. Consequently, enzymatic hydrolysis using myrosinase is a more efficient and specific strategy.

Experimental Protocol: Preparation of Glucosinolate Derivatives via Myrosinase [18]

Source of Myrosinase: The enzyme can be obtained from:

- Endogenous Plant Myrosinase: Released by homogenizing fresh cruciferous vegetable tissue (e.g., broccoli seeds, daikon radish).

- Heterologously Expressed Myrosinase: Produced in microbial systems like E. coli or Pichia pastoris for higher purity and activity [18].

Hydrolysis Reaction:

- Substrate: A glucosinolate-rich extract is prepared from plant material or using a purified standard.

- Reaction Setup: The substrate is mixed with the myrosinase preparation in a suitable buffer (e.g., phosphate buffer, pH ~6.5-7.0). Ascorbic acid may be added as a cofactor, as myrosinase is the only known enzyme to use it [18].

- Incubation: The reaction is typically carried out at temperatures between 20-37°C for a defined period (minutes to a few hours).

- Termination and Analysis: The reaction is stopped by heat inactivation or solvent addition. The hydrolysis products (e.g., sulforaphane) are then analyzed and quantified using techniques like HPLC or LC-MS/MS.

Challenges and Optimization: Key challenges in scaling up production include ensuring high myrosinase activity, stabilizing the pathway, and efficiently supplying precursors. The use of exogenous myrosinase preparations generally offers higher conversion efficiency and better control over the reaction compared to relying on endogenous plant enzymes [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Bioactive Compound Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| UPLC-ESI-MS/MS System | High-resolution separation and sensitive identification/quantification of metabolites. | Profiling alkaloids in plant extracts [16]; quantifying glucosinolate hydrolysis products [18]. |

| Triple Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer (QTRAP) | Quantitative analysis in Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) mode for targeted metabolomics. | Precise quantification of a predefined list of alkaloids or phenolics [16]. |

| Myrosinase Preparation | Key enzyme for hydrolyzing glucosinolates to produce bioactive isothiocyanates. | Enzymatic preparation of sulforaphane from glucoraphanin for bioactivity studies [18]. |

| Immobilized Enzyme Systems | Enzymes fixed to an inert support to enhance stability, reusability, and ease of separation. | Continuous biotransformation of phenolic acids in a flow reactor [13]. |

| HSS-T3 UPLC Column | Reversed-phase chromatography column designed for high-resolution separation of polar small molecules. | Separating complex mixtures of phenolic acids or alkaloids prior to mass spectrometric detection [16]. |

| Methanol, Acetonitrile, Formic Acid | Common solvents and mobile phase additives for metabolite extraction and LC-MS analysis. | Extraction of alkaloids with methanol:acetonitrile:water mixture [16]; mobile phase for UPLC separation [16]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Sample | A pooled sample from all individual extracts used to monitor instrument performance during analytical runs. | Ensuring data reproducibility in large-scale metabolomics studies [16]. |

The quest for novel therapeutic agents often leads researchers back to the origins of medicine: the plant kingdom. The discoveries of aspirin from willow bark (Salix spp.) and artemisinin from sweet wormwood (Artemisia annua L.) stand as monumental success stories in natural product drug discovery [19] [20]. These cases exemplify a successful paradigm that integrates traditional medicinal knowledge with modern scientific validation, providing a robust framework for future bioprospecting efforts. This review examines the historical context, discovery pathways, chemical elucidation, and mechanistic actions of these plant-derived compounds, framing them within the broader thesis of discovering bioactive compounds from plants. We further provide detailed experimental protocols and analytical approaches to guide contemporary research aimed at unlocking the next generation of plant-derived therapeutics.

Willow Bark to Aspirin: The Foundation of Modern Analgesia

Historical Use and Initial Chemical Characterization

The use of willow bark as an analgesic and antipyretic agent dates back to ancient civilizations, including the Egyptians and Greeks, with Hippocrates himself recommending willow leaves and bark for pain and fever relief [19]. The modern scientific journey began in 1763 when Edward Stone conducted a systematic study, prescribing approximately 1 gram of powdered willow bark in water every four hours to relieve fever [19]. The 19th century saw critical advancements in chemical isolation: in 1828, Johann Buchner purified the bitter-tasting yellow glycoside salicin from willow bark [19]. A decade later, Raffaele Piria hydrolyzed salicin to obtain salicylic acid, establishing the core chemical structure that would lead to the development of aspirin [19].

The Path to Synthesis and Commercialization

The therapeutic potential of salicylic acid was offset by severe gastrointestinal side effects, including stomach irritation and an unpleasant taste [19]. This limitation prompted chemists at Bayer to seek a better-tolerated derivative. In 1897, chemist Felix Hoffman successfully synthesized acetylsalicylic acid in a pure and stable form, a discovery that would become the pharmaceutical blockbuster Aspirin [19]. Marketed initially in powder form, aspirin became available as tablets in 1911, providing patients with precise dosing [19]. Its mechanism of action, primarily through irreversible inhibition of cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, would not be fully elucidated until much later, solidifying its role as a prototypical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID).

Modern Phytochemical and Pharmacological Insights

Contemporary research continues to reveal the complexity of willow bark's phytochemistry, which extends beyond salicin to include a suite of bioactive compounds. As shown in Table 1, modern HPLC-DAD analyses identify salicin, chlorogenic acid, rutin, and epicatechin as major constituents in various Salix species [21]. The total phenolic content in bark extracts can range from 4.94 to 50.86 mg GAE/g of dry extract, with S. purpurea exhibiting the highest concentrations [21]. These compounds contribute to a synergistic antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effect that is not solely attributable to salicin [21]. Studies show that standardized willow bark extracts can more effectively suppress pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IL-6 than acetylsalicylic acid alone, suggesting contributions from flavonoid and phenolic constituents [21].

Table 1: Bioactive Compound Yields from Select Salix Genotypes

| Species/Genotype | Salicin in Bark (mg/g) | Total Phenolics (mg GAE/g d.e.) | Total Flavonoids (mg QE/g d.e.) | Salicin Yield (kg ha⁻¹ y⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. purpurea × S. daphnoides | ~29.0 | 50.86 (Bark) | 17.48 (Bark) | >92 |

| S. americana UWM 094 | Information Missing | 26.96 (Leaf) | 16.66 (Leaf) | Information Missing |

| S. alba | 4.5 | 25.14 (Bark) | 1.80 (Bark) | Information Missing |

| S. fragilis | Information Missing | 4.94 (Bark) | 1.94 (Bark) | Information Missing |

Abbreviations: GAE, gallic acid equivalents; d.e., dry extract; QE, quercetin equivalents. Data compiled from [22] and [21].

Furthermore, recent investigations have uncovered novel therapeutic applications for willow bark extracts. A 2023 study demonstrated that a hot water extract of willow bark exhibits broad-spectrum antiviral activity against both enveloped coronaviruses and non-enveloped enteroviruses [23]. The extract appears to act on the viral surface, causing enveloped viruses to degrade and non-enveloped viruses to become unable to release their genetic material [23]. This activity is not replicated by pure salicin or commercial salixin powders, indicating that the effect arises from a complex mixture of bioactive compounds within the extract [23].

Artemisia to Artemisinin: A Modern Antimalarial Triumph

Rediscovery from Traditional Chinese Medicine

The discovery of artemisinin is a premier example of the successful mining of traditional knowledge systems. In 1969, Chinese scientist Tu Youyou and her team were assigned by the government to find a new antimalarial treatment, a project initiated under Project 523 to protect soldiers from drug-resistant malaria during the Vietnam War [20] [24]. Their systematic review of ancient Chinese medical texts led them to Artemisia annua (qinghao or sweet wormwood), a plant used for "intermittent fevers" – a hallmark of malarial infection [20] [24]. A critical breakthrough came from a fourth-century text, A Handbook of Prescriptions for Emergencies, which described a method of preparing the herb without heat: "Immerse a handful of the herb in water, then wring out the juice and drink it all" [24]. This instruction prompted Tu's team to switch from a high-temperature extraction to a low-temperature, ether-based extraction method, which preserved the antimalarial activity [24]. The resulting extract demonstrated 100% efficacy against malaria in animal models and later in human clinical trials [24].

Isolation, Structural Elucidation, and Development

The active compound, a sesquiterpene lactone containing a unique endoperoxide bridge, was isolated in 1972 and named artemisinin (formerly known as qinghaosu) [20]. Its novel structure and potent activity against Plasmodium parasites, including chloroquine-resistant strains, represented a breakthrough in antimalarial pharmacology [20]. The endoperoxide bridge is essential for its mechanism of action, which involves iron-mediated cleavage within the parasite to generate cytotoxic free radicals that damage parasitic proteins and membranes [25]. To improve solubility and efficacy, semi-synthetic derivatives such as artemether, arteether, and artesunate were developed [26] [24]. These derivatives, often used in Artemisinin-based Combination Therapies (ACTs), now form the cornerstone of modern antimalarial treatment [26].

Contemporary Research and New Therapeutic Indications

Recent research has significantly expanded the potential applications of artemisinin and its derivatives beyond malaria. A landmark 2024 study used high-throughput screening of a 5,000-compound library on human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiac fibroblasts to discover that artesunate, a water-soluble artemisinin derivative, is a potent anti-fibrotic agent [24]. The study demonstrated that artesunate could partially reverse cardiac fibrosis in patient-derived cells and improve heart function in mouse models of heart failure [24]. Notably, the anti-fibrotic mechanism is distinct from its antimalarial action; it involves the MD-2/TLR4 signaling pathway to inhibit the expression of fibrotic genes [24]. This discovery highlights the potential for drug repurposing based on rigorous, modern screening techniques.

Table 2: Key Bioactive Compounds in Artemisia annua and Their Activities

| Compound Class | Example Compounds | Reported Biological Activities |

|---|---|---|

| Sesquiterpenes | Artemisinin, Arteannuin B, Artemisinic acid | Antimalarial, Antifibrotic, Anticancer, Antiviral |

| Monoterpenes | 1,8-cineole, α/β-pinene, Camphor, Limonene | Insecticidal, Antibacterial, Anti-inflammatory, Antioxidant |

| Flavonoids | Chrysosplenol, Casticin, Cirsilineol | Antioxidant, Anti-inflammatory, Chemosensitizing |

| Phenolic Acids | Chlorogenic acid, Rosmarinic acid | Antioxidant, Anti-inflammatory |

Data sourced from [25] and [27].

Moreover, the chemical richness of Artemisia annua extends beyond artemisinin. The plant produces over 600 secondary metabolites, including monoterpenes, flavonoids, and phenolic acids, which contribute to a wide array of documented biological activities such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antifungal, and antitumor effects [25] [27]. This chemical diversity, as summarized in Table 2, underscores the plant's significant potential as a source of not just a single drug, but multiple therapeutic agents.

Experimental Protocols for Bioactive Compound Discovery

The successful isolation and characterization of plant-derived bioactive compounds require a structured workflow from extraction to biological testing. The following protocols are adapted from contemporary research on Salix and Artemisia species.

Plant Material Extraction and Preparation

Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) for Willow Bark [21]:

- Preparation: Harvest commercially grown willow branches. Separate the bark, cut it into small pieces, freeze, and grind into a fine powder.

- Extraction: Subject the powdered bark (e.g., 5 g) to ultrasound-assisted extraction with a suitable solvent (e.g., 70% ethanol or hot water) at a defined solid-to-solvent ratio (e.g., 1:20).

- Parameters: Maintain a controlled temperature (e.g., 40-50°C) for a specific duration (e.g., 30-60 minutes) using an ultrasonic bath or probe system.

- Recovery: Filter the extract, concentrate under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator, and lyophilize to obtain a dry extract for subsequent analysis.

Low-Temperature Solvent Extraction for Artemisia annua (based on the historical method) [24]:

- Preparation: Obtain dried leaves of Artemisia annua and pulverize.

- Extraction: Macerate the powdered plant material in a non-polar or low-polarity solvent such as diethyl ether or hexane at room temperature for 24-48 hours. Alternatively, a Soxhlet apparatus can be used for continuous extraction.

- Concentration: Filter the solution and carefully evaporate the solvent at low temperatures (<40°C) under reduced pressure to obtain a crude extract rich in artemisinin and other lipophilic compounds.

Phytochemical Profiling and Compound Identification

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Diode-Array Detection (HPLC-DAD) [21]:

- Instrument Setup: Utilize a reversed-phase C18 column (e.g., 250 mm x 4.6 mm, 5 μm). The mobile phase typically consists of water with a weak acid (e.g., 0.1% formic acid) and acetonitrile or methanol.

- Gradient Elution: Employ a linear gradient from 5% to 100% organic solvent over 30-60 minutes with a flow rate of 0.8-1.0 mL/min.

- Detection & Identification: Monitor eluents at 200-400 nm. Identify compounds by comparing their retention times and UV-Vis spectra with those of authentic standards (e.g., salicin, chlorogenic acid, rutin, artemisinin).

- Quantification: Generate a calibration curve for each standard to quantify the concentration of target compounds in the extract, expressed as mg per gram of dry plant material or dry extract.

Biological Activity Assessment

Cytopathic Effect Inhibition Assay for Antiviral Screening [23]:

- Cell and Virus Culture: Grow susceptible cell lines (e.g., Vero cells) in standard culture medium. Propagate and titrate the target virus (e.g., enterovirus, coronavirus).

- Pre-treatment: Incubate cells with various non-cytotoxic concentrations of the plant extract for a pre-defined period (e.g., 1 hour).

- Infection: Infect pre-treated cells with the virus at a specific multiplicity of infection (MOI).

- Analysis: After a suitable incubation period, assess viral-induced cytopathic effect (CPE) microscopically or by using cell viability assays like MTT. Calculate the percentage of inhibition compared to infected, untreated control cells.

High-Throughput Screening for Anti-fibrotic Activity [24]:

- Cell Line Development: Generate human cardiac fibroblasts from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). Genetically engineer them to carry a fluorescent reporter gene under the control of a fibrotic response element.

- Automated Screening: Use robotic systems to seed cells into 384-well plates. Stimulate fibroblasts with a pro-fibrotic agent (e.g., TGF-β) and simultaneously treat with compounds from a chemical library.

- Signal Detection: After incubation, measure fluorescence intensity as a proxy for fibrotic activity using a high-content imaging system or plate reader.

- Data Analysis: Apply machine-learning algorithms to identify "hits" that significantly inhibit the fibrotic response without causing cytotoxicity, which is assessed in parallel.

Visualization of Research Workflows and Mechanisms

The following diagrams, generated using DOT language, illustrate the core experimental workflows and mechanistic pathways discussed in this review.

Historical Bioactive Compound Discovery Pipeline

Diagram 1: A generalized workflow for discovering bioactive compounds from plants, integrating traditional knowledge with modern pharmacological and chemical analysis techniques. This pipeline underpins the successes of both aspirin and artemisinin.

Mechanism of Artemisinin's Anti-fibrotic Action

Diagram 2: The proposed molecular mechanism for artesunate's newly discovered anti-fibrotic activity. Artesunate targets the MD-2/TLR4 complex to inhibit the NF-κB signaling pathway, leading to reduced expression of pro-fibrotic genes and ultimately improved cardiac function [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Plant-Based Drug Discovery Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Human-induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Differentiation into disease-relevant cell types (e.g., cardiac fibroblasts) for human-specific, physiologically relevant screening. | High-throughput anti-fibrotic drug screening [24]. |

| Ultrasound Probe/Bath | Enhances extraction efficiency of bioactive compounds from plant matrix through cavitation. | Ultrasound-assisted extraction of phenolics from willow bark [21]. |

| HPLC-DAD/MS System | Separation, identification, and quantification of chemical constituents in complex plant extracts. | Phytochemical profiling of Salix and Artemisia extracts [21] [25]. |

| High-Content Imaging System | Automated, quantitative analysis of cellular phenotypes and fluorescent reporters in multi-well plates. | Measuring fibrotic response in iPSC-derived fibroblasts [24]. |

| Cytopathic Effect (CPE) Inhibition Assay Kit | Measures the ability of a compound to protect cells from virus-induced destruction. | Assessing antiviral activity of willow bark extract [23]. |

The stories of aspirin and artemisinin provide a powerful testament to the value of ethnobotanical knowledge as a starting point for scientific discovery. However, modern technological advancements have dramatically accelerated and refined the process. The integration of green extraction techniques, advanced chromatographic and spectroscopic tools for phytochemical profiling, and sophisticated high-throughput biological screening platforms represents the new frontier in natural product research.

Future success will depend on interdisciplinary collaboration among botanists, phytochemists, pharmacologists, and clinicians. Furthermore, the application of omics technologies (genomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics) and synthetic biology to understand and optimize the biosynthetic pathways of valuable plant-derived compounds like artemisinin will be crucial for ensuring sustainable supply and discovering novel analogs [26]. As evidenced by the recent discovery of artesunate's anti-fibrotic properties, the systematic investigation of plant-based medicines, guided by both traditional wisdom and cutting-edge science, continues to hold immense promise for addressing unmet medical needs. The legacy of the willow bark and Artemisia is a continuing narrative of discovery, reminding us that the next breakthrough therapeutic agent may already be growing in nature, awaiting revelation through rigorous scientific inquiry.

Ecological and Evolutionary Roles of Phytochemicals in Plant Defense and Signaling

Within the broader thesis on the discovery of bioactive compounds from plants, this whitepaper delineates the integral ecological and evolutionary functions of phytochemicals, particularly plant secondary metabolites. These compounds are not directly involved in primary growth processes but are indispensable for plant survival, mediating defense against herbivores and pathogens, facilitating ecological interactions, and contributing to adaptive fitness [28] [29]. From a drug discovery perspective, these ecological roles are a rich source of evolutionary-optimized bioactive scaffolds. The continuous arms race between plants and their stressors has driven the evolution of a vast chemical repertoire with high affinity for biological targets, providing a valuable resource for developing new pharmaceuticals, biopesticides, and functional food ingredients [28] [30]. This document provides a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals, detailing the mechanisms, methodologies, and applications of phytochemical research.

Phytochemical Defense Mechanisms and Ecological Functions

Plants employ a diverse array of secondary metabolites as strategic chemical defenses. The major classes of these compounds and their specific ecological roles are summarized in the table below, which synthesizes quantitative and qualitative data from recent research [28] [29].

Table 1: Major Classes of Phytochemicals and Their Ecological Roles in Defense and Signaling

| Phytochemical Class | Representative Compounds | Primary Ecological Functions & Bioactivities | Quantitative Efficacy Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkaloids | Quinine, Morphine, Berberine | Defense against herbivores (toxicity, feeding deterrence); antimicrobial properties [29]. | - |

| Flavonoids & Polyphenols | Myricitrin, Ellagic acid, Quercetin, Catechins | Antioxidant activity; antifungal and antibacterial defense; attraction of pollinators [28] [31]. | Antifungal activity (Eugenia uniflora fractions): MIC of 62.5–500 µg/mL against Candida strains [28]. |

| Terpenoids | Betulin, Lupeol, Taxol | Direct toxicity to herbivores and pathogens; volatile signals for plant-plant communication [29] [32]. | Filsuvez gel: 72–88% betulin, approved for wound treatment (JEB/DEB) [30]. |

| Glucosinolates | Sulforaphane, Indole-3-carbinol | Constitute the "mustard oil bomb"; deter herbivores and possess anti-carcinogenic properties [31]. | - |

| Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) | Jasmonates, Ethylene | Airborne signaling for intra- and inter-plant defense priming; indirect defense by attracting predators of herbivores [33]. | - |

These defense mechanisms are not isolated but are part of a complex, integrated signaling network. Key endogenous signaling molecules, such as jasmonic acid, salicylic acid, and ethylene, regulate the production and deployment of many defense-related secondary metabolites in response to biotic and abiotic stressors [33]. The following diagram illustrates the interconnected signaling pathways that modulate plant defense responses.

Diagram 1: Plant Defense Signaling Pathways

Furthermore, plants can engage in pre-emptive defense through systemic resistance mechanisms primed by beneficial microorganisms. For instance, fungi from the Trichoderma genus not only produce direct antifungal metabolites but also induce systemic resistance (ISR) in plants, enhancing their innate defensive capacity against future pathogen attacks [32].

Experimental Methodologies for Phytochemical Research

The discovery and investigation of bioactive phytochemicals involve a multi-step workflow, from efficient extraction to advanced structural and functional analysis. The following diagram outlines this integrated process.

Diagram 2: Phytochemical Research Workflow

Extraction and Isolation Protocols

The initial step requires optimizing extraction to efficiently release metabolites from the plant matrix while preserving their bioactivity.

Green Extraction Techniques: Modern methods are favored for their efficiency, selectivity, and reduced environmental impact [28].

- Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE): Often uses supercritical CO₂. It is tunable by adjusting pressure and temperature and allows for the isolation of volatile to medium-polarity fractions with minimal solvent residue [28] [31]. Protocol Example: For Sorbus aucuparia fruits, SFE is performed using CO₂ with methanol as a co-solvent under varied temperature and pressure conditions to obtain bioactive fractions [28].

- Pressurized Hot Water Extraction (PHWE): Uses water above 100°C under pressure. Under these conditions, water behaves similarly to organic solvents, effectively extracting polar metabolites like phenolics without organic solvents [28].

- Ultrasound- (UAE) and Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE): These techniques use physical waves to disrupt cell walls, reducing extraction time and solvent consumption [28] [31].

- Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES): These are biodegradable mixtures (e.g., choline chloride and organic acids) that offer a wide solubility window and can selectively extract specific metabolite classes, often eliminating the need for desolventization [28] [31].

Conventional Techniques: Methods like reflux extraction and maceration remain relevant. For example, a study on Scutellaria baicalensis roots recommended reflux extraction with ethanol for 2 hours as the most effective and safe method to obtain flavonoid-rich extracts, avoiding the formation of undesirable compounds like 5-hydroxymethylfurfural that can occur in Soxhlet extraction [28].

Analytical and Dereplication Strategies

Advanced analytics are crucial for mapping the chemical space of complex extracts and identifying known compounds early.

- LC-HRMS/MS and Metabolomics: Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography coupled with high-resolution tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-HRMS/MS) is the cornerstone of modern phytochemical analysis. It enables the separation and accurate mass determination of numerous metabolites in a single run [28] [34].

- Dereplication and Molecular Networking: To avoid re-isolating known compounds, dereplication is performed by comparing acquired MS/MS spectra with chemical databases. Feature-Based Molecular Networking (FBMN) on platforms like GNPS clusters spectra based on similarity, visually mapping the chemical diversity of an extract and highlighting novel or unusual metabolites for prioritization [28].

Biological Activity Screening

Bioassays guide the isolation process toward compounds with therapeutic or agrochemical potential.

- Antimicrobial Assays: Standardized tests like Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Fungicidal Concentration (MFC) determinations are used to evaluate efficacy against plant and human pathogens. Biofilm inhibition assays are also increasingly common for assessing anti-virulence potential [28] [35].

- Antioxidant Assays: Various in vitro methods (e.g., DPPH, ABTS, FRAP) are employed to quantify the free radical scavenging capacity of extracts and compounds, which is relevant for health-promoting and food-preserving applications [31] [34].

- Enzyme Inhibition Assays: These target-specific assays are vital for drug discovery. For example, an in-capillary CE-DAD method was developed for rapid screening of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitors from natural extracts, which is relevant for Alzheimer's disease research [35].

- In Silico Screening: Molecular docking is used to predict the interaction between phytochemicals and protein targets, prioritizing candidates for labor-intensive experimental testing. For instance, docking studies have identified phytochemicals with high binding affinity for targets like SARS-CoV-2 3CL protease and NLRP3 [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful phytochemical research relies on a suite of specialized reagents, solvents, and materials. The following table details essential items for the workflows described.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Phytochemical Investigation

| Reagent/Material | Specification/Example | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Extraction Solvents | Supercritical CO₂, NADES (e.g., Choline Chloride:Glycerol), Ethanol, Pressurized Hot Water | To efficiently and selectively dissolve target metabolites from plant biomass with minimal degradation [28] [31]. |

| Chromatography Media | C18 Silica Gel, Sephadex LH-20, Diatomaceous Earth | For fractionation and purification of crude extracts via column chromatography or solid-phase extraction [28]. |

| Analytical Standards | Certified reference compounds (e.g., Quercetin, Berberine, Gallic Acid) | For instrument calibration, quantification, and compound identification by matching retention time and mass spectra [31] [34]. |

| Bioassay Reagents | DPPH (2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl), ATCC microbial strains, MTT cell viability dye, specific enzyme substrates (e.g., Acetylthiocholine for AChE) | To quantitatively evaluate biological activities such as antioxidant potential, antimicrobial efficacy, cytotoxicity, and enzyme inhibition [28] [31] [35]. |

| Computational Software | AutoDock Vina, Schrödinger Suite, GNPS (Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking) | For in silico prediction of target binding (molecular docking), metabolic pathway analysis, and dereplication via molecular networking [28] [36]. |

The ecological and evolutionary roles of phytochemicals in plant defense and signaling are fundamentally linked to their value as bioactive compounds for human use. The defense functions of these metabolites, refined through millions of years of evolutionary pressure, represent a pre-optimized library of complex chemical scaffolds with inherent biological activity. Integrating modern "green" extraction technologies, advanced analytical platforms like LC-HRMS/MS and molecular networking, and robust biological screening is essential for translating these ecological functions into applications. For drug discovery professionals, this field offers a promising pathway to novel therapeutics, as evidenced by the continued approval of natural product-derived drugs. Future research will be driven by interdisciplinary approaches that combine molecular biology, microbial ecology, and computational tools to fully harness the potential of plant chemical diversity for sustainable agriculture, medicine, and food technology.

The lexicon of plant biochemistry is undergoing a significant transformation, with the term "specialized metabolites" progressively replacing the traditional "secondary metabolites." This shift is not merely semantic but reflects a fundamental evolution in our understanding of plant chemistry and its applications in bioactive compound discovery. Historically, plant metabolites were categorized as either primary—those essential for growth, development, and reproduction—or secondary, considered non-essential byproducts [37] [3]. The term "secondary metabolite" was first coined by Albrecht Kossel in 1910 and later refined by Friedrich Czapek as end products of nitrogen metabolism [37] [38].

Contemporary research now recognizes that these compounds are far from "secondary" in importance. They mediate crucial ecological interactions that provide selective advantages by increasing an organism's survivability and fecundity [37] [39]. The newer terminology, "specialized metabolites," more accurately captures their specialized functions in plant defense, pollination, and environmental adaptation, while also reflecting their frequent restriction to narrow phylogenetic lineages [37] [40]. This conceptual framework is particularly relevant for researchers focused on discovering bioactive compounds, as it acknowledges the sophisticated chemical strategies plants employ for survival—strategies that can be harnessed for pharmaceutical development.

The Conceptual Evolution: From "Secondary" to "Specialized"

Limitations of the Traditional "Secondary" Concept

The traditional dichotomy between primary and secondary metabolites has become increasingly difficult to uphold [39]. This classification system implied a hierarchy of importance that has been undermined by several key observations:

- Functional Essentiality: While not directly involved in core growth processes, specialized metabolites are indispensable for plant survival in natural environments, serving as defenses against herbivores, pathogens, and environmental stresses [37] [38].

- Blurred Boundaries: Certain vital compounds, including phytosterols and hormones like gibberellins and abscisic acid, are produced through secondary metabolic pathways such as the terpenoid biosynthetic route, despite their essential roles across plant taxa [39].

- Dynamic Interpretation: The current border between primary and specialized metabolism represents merely a "tentative snapshot" in the dynamic continuum of metabolic evolution [40].

The "Specialized" Paradigm: Implications for Bioactive Compound Discovery

The specialized metabolism concept better aligns with the contemporary understanding of plant chemical ecology and its applications in drug discovery:

- Lineage-Specific Innovation: Specialized metabolites often arise through lineage-specific evolution of biosynthetic pathways, explaining why identical specialized metabolites sometimes exist in phylogenetically remote lineages through convergent evolution [40].

- Chemical Diversity Source: The structural uniqueness of specialized metabolites suggests their evolutionary origins are relatively recent compared with conserved primary metabolites, contributing to the vast structural diversity observed in nature [40].

- Bioactivity Potential: The lineage-specific nature of these compounds represents an untapped reservoir of structural novelty with potential pharmaceutical applications, as these molecules have been optimized through evolution for specific biological interactions [40] [38].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Terminology and Conceptual Frameworks

| Aspect | "Secondary Metabolites" Terminology | "Specialized Metabolites" Terminology |

|---|---|---|

| Conceptual Basis | Implies hierarchy and non-essentiality | Emphasizes ecological function and adaptation |

| Evolutionary Perspective | Considered evolutionarily recent | Viewed as products of continuous dynamic evolution |

| Taxonomic Distribution | Sporadic across phylogeny | Often restricted to specific lineages |

| Research Implications | Focus on isolation and structure elucidation | Focus on ecological context and biosynthetic gene clusters |

| Pharmaceutical Relevance | Source of lead compounds | Source of target-specific bioactives with ecological validation |

Fundamental Classes of Specialized Metabolites

Plant specialized metabolites are broadly classified into three major categories based on their biosynthetic origins, each with distinct characteristics and pharmaceutical relevance.

Terpenoids (Isoprenoids)

Terpenoids represent one of the largest and most structurally diverse classes of specialized metabolites, with over 40,000 identified structures [38]. They are synthesized from isoprene units (C5H8) and classified based on the number of these units [37] [41]:

Table 2: Classification and Pharmaceutical Significance of Terpenoids

| Class | Isoprene Units | Carbon Atoms | Representative Examples | Bioactivities and Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monoterpenes | 2 | C10 | Limonene, Carvone | Flavoring agents, antimicrobials [41] |

| Sesquiterpenes | 3 | C15 | Caryophyllene, Farnesol | Antibacterial, antiprotozoal, antifungal activities [41] |

| Diterpenes | 4 | C20 | Gibberellins, Paclitaxel (precursor) | Antifungal, antibacterial, analgesic, anti-inflammatory, antineoplastic [41] |

| Triterpenes | 6 | C30 | Quassin, Saponins | Anticancer, anti-inflammatory [37] [41] |

| Tetraterpenes | 8 | C40 | Carotenoids, Xanthophylls | Antioxidants, provitamin A activity [41] |

Notable pharmaceutical terpenoids include artemisinin (an antimalarial from Artemisia annua) and paclitaxel (a chemotherapeutic from the Pacific Yew) [37]. The biosynthesis of terpenoids occurs via two primary pathways: the mevalonic acid (MVA) pathway in the cytoplasm and the methylerythritol-4-phosphate (MEP) pathway in plastids [42].

Phenolic Compounds

Phenolics constitute the most abundant group of specialized metabolites in plants, characterized by aromatic rings with one or more hydroxyl groups [37] [41]. Their structural diversity ranges from simple phenolic acids to highly polymerized tannins [37].

Table 3: Major Classes of Phenolic Compounds and Their Bioactivities

| Class | Carbon Skeleton | Representative Examples | Bioactivities and Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Phenolics | C6 | Gallic acid, Salicylic acid | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory [41] |

| Flavonoids | C6-C3-C6 | Quercetin, Cyanidin | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, immune system benefits [3] |

| Lignans | (C6-C3)2 | Matairesinol | Antioxidant, phytoestrogenic activities [41] |

| Stilbenes | C6-C2-C6 | Resveratrol | Cardioprotective, anticancer potential [37] [41] |

| Tannins | Varies | Gallotannins, Ellagitannins | Antioxidant, antimicrobial, protein-binding [41] |

Flavonoids represent the largest subgroup of phenolics, with over 6000 identified types [3]. They demonstrate significant antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial activities, and can function as signaling molecules in mammalian systems [3]. Recent research has also revealed their synergistic activity with antibiotics, suppressing bacterial loads [37].

Nitrogen-Containing Compounds

Alkaloids

Alkaloids are a heterogeneous group of approximately 12,000 compounds characterized by nitrogen atoms in their structures [37] [38]. They are produced by various organisms, including plants, animals, fungi, and bacteria [41].

Pharmaceutically significant alkaloids include:

- Morphine and codeine from opium poppy (Papaver somniferum) for pain relief [37]

- Atropine from Atropa belladonna used to treat bradycardia and as an antidote to organophosphate poisoning [37]

- Vincristine and vinblastine from Catharanthus roseus as mitotic inhibitors in cancer therapy [37]

- Cocaine from Erythroxylum coca with anesthetic and stimulant properties [37]

- Caffeine from coffee and tea plants as a central nervous system stimulant [41]

Alkaloids frequently exhibit potent biological activities, often by interacting with neurotransmitter receptors in animals [37]. Their biosynthesis typically originates from amino acid precursors such as tyrosine, tryptophan, or ornithine [38].

Glucosinolates

Glucosinolates are sulfur- and nitrogen-containing compounds characteristic of the Brassicaceae family. An example is glucoraphanin from broccoli, which has demonstrated chemopreventive properties [37]. Upon tissue damage, glucosinolates are hydrolyzed by myrosinase enzymes to produce bioactive isothiocyanates with significant anticancer activities.

Advanced Methodologies for Studying Specialized Metabolites

Multi-Omics Integration in Metabolite Research

Contemporary research on specialized metabolites increasingly relies on integrated multi-omics approaches to overcome the limitations of traditional isolation-based methods [43].

Diagram 1: Multi-Omics Workflow for Specialized Metabolite Discovery

Mass spectrometry-based metabolomics has become the cornerstone approach for comprehensive analysis of specialized metabolites [43] [44]. The development of molecular networking approaches on platforms like GNPS (Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking) has revolutionized metabolite annotation by visualizing structural relationships among compounds with similar MS/MS fragmentation patterns, enabling the propagation of known annotations to structurally similar unknown derivatives [44].

Experimental Protocol: Metabolite Extraction and Analysis

Protocol: Solvent Optimization for Metabolite Extraction from Medicinal Plants

Based on the comprehensive study of 248 Korean medicinal plants [44]:

Sample Preparation:

- Obtain dried medicinal plant samples and grind into coarse powders using a blender

- Store powdered samples refrigerated before extraction to prevent degradation

Extraction Solvent Systems:

- Prepare three solvent systems with varying polarity:

- 100% water (high polarity)

- 50% ethanol (medium polarity)

- 100% ethanol (low polarity)

- Include internal standard (e.g., 1 µM sulfamethazine) for quantification

- Prepare three solvent systems with varying polarity:

Extraction Procedure:

- Accurately weigh 1 g of powdered sample

- Mix with 30 mL of the respective solvent

- Perform ultrasonic extraction at 25°C for 3 hours

- Filter the solution using filter paper to remove solid residues

Sample Concentration:

- Transfer 500 µL of clear filtrate to a clean vial

- Dry using a speed vacuum concentrator

- Reconstitute in 50% methanol containing a second internal standard (e.g., 1 µM sulfadimethoxine) to a final concentration of 500 ppm

- Filter through a 0.22 µm RC syringe filter before UHPLC-MS analysis

UHPLC-MS Analysis:

- Column: ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 (50 × 2.1 mm, 1.7 µm)

- Mobile Phase: (A) water with 0.1% formic acid; (B) acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid

- Gradient: 10% B to 90% B over 14.5 minutes, hold for 2.5 minutes

- Flow Rate: 0.3 mL/min

- Injection Volume: 5 µL

- MS Detection: Full-scan MS in data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode, m/z 50-1500

Data Processing:

- Convert raw data to mzML format using MSConvert

- Perform feature extraction using MZmine 3.9.0

- Apply ion identity networking to minimize feature splitting

- Export data for molecular networking and in silico annotation

This protocol highlights the critical importance of solvent selection, as different polarities extract distinct metabolite classes, with water extracting highly polar compounds and ethanol favoring lower polarity metabolites [44].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Technologies

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Specialized Metabolite Studies

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| UHPLC-MS Systems | Separation and detection of metabolites | High resolution, sensitivity, compatibility with diverse metabolite classes [44] |

| C18 Chromatography Columns | Reverse-phase separation of metabolites | Standard for natural product analysis, compatible with aqueous-organic mobile phases [44] |

| Solvent Systems | Extraction of metabolites of varying polarity | Water, ethanol, methanol, acetonitrile; polarity determines metabolite recovery [44] |

| Molecular Networking (GNPS) | Annotation of metabolite structures | Visualizes structural relationships, propagates annotations across similar compounds [44] |

| In Silico Annotation Tools | Prediction of compound classes | Deep learning approaches for structural prediction when reference standards are unavailable [44] |

| Hairy Root Cultures | Production of specialized metabolites | Sustainable alternative to wild harvesting, stable production of root-derived metabolites [39] |

| Elicitors (Yeast Extract, MJ) | Induction of metabolite biosynthesis | Stimulate plant defense responses, enhancing production of defensive compounds [39] |

Regulatory Mechanisms and Metabolic Engineering

Light-Mediated Regulation of Specialized Metabolism

Light serves as a key environmental factor regulating the synthesis of plant specialized metabolites through multidimensional mechanisms [42]. Understanding these regulatory networks provides opportunities for enhancing bioactive compound production.

Diagram 2: Light Regulation of Specialized Metabolite Biosynthesis

Specific Light Qualities and Their Effects:

UV Light: Activates the UVR8 photoreceptor, promoting combination with COP1 and activating HY5 transcription factor, which induces expression of phenylpropanoid pathway enzymes (PAL, CHS) [42]. This enhances synthesis of flavonoids, anthocyanins, and phenolics with protective functions [42].

Blue Light: Mediated by cryptochrome and phototropin photoreceptors, influences phenylpropanoid metabolism through transcriptional regulators like HY5 and MYB [42].

Red Light: Modulates terpenoid production through phytochrome-mediated hormonal signaling pathways that alter endogenous hormone levels [42].

Light intensity dynamically modulates secondary metabolite accumulation by affecting photosynthetic efficiency and energy allocation, while photoperiod coordinates metabolic rhythms through circadian clock genes [42]. These light-responsive mechanisms constitute a chemical defense strategy that enables plants to adapt to their environment while providing critical targets for directed regulation of medicinal components.

Metabolic Engineering and Synthetic Biology Approaches

The sustainable production of valuable specialized metabolites has been significantly advanced through metabolic engineering and synthetic biology:

Hairy Root Cultures: Engineered Centella asiatica hairy roots have been developed for enhanced centelloside production, providing a sustainable alternative to wild harvesting [39].

Pathway Reconstruction: Recent synthetic biology efforts have successfully reconstructed entire biosynthetic pathways in heterologous systems, revealing the minimal gene sets required for complex metabolite biosynthesis such as paclitaxel [39] [44].

Cytoplasmic Engineering: Engineering of cytoplasmic pathways in Nicotiana benthamiana has enabled efficient production of miltiradiene, a key intermediate of tanshinones, providing an alternative platform to microbial systems [43].

Transcription Factor Modulation: Altering regulator genes to enhance the biosynthesis of target specialized metabolites has emerged as a powerful strategy for increasing yield [38].

Implications for Bioactive Compound Discovery

The paradigm shift from "secondary" to "specialized" metabolites has profound implications for drug discovery and development:

Ecological Function as a Guide for Bioactivity

The ecological roles of specialized metabolites provide valuable insights for their potential pharmaceutical applications:

Defense Compounds as Antimicrobials: Plants produce a plethora of antimicrobial specialized metabolites as defense mechanisms against pathogens, serving as excellent leads for developing new antibiotics [37] [38].

Herbivore Deterrents as Neurological Agents: Compounds that deter herbivores through neurological effects (e.g., alkaloids interacting with neurotransmitter receptors) offer templates for developing neuroactive pharmaceuticals [37].

UV-Protectants as Antioxidants: Flavonoids and phenolics that protect plants from UV damage often possess potent antioxidant activities relevant for combating oxidative stress in human diseases [37] [42].

Technological Advances Driving Discovery

Recent technological innovations are accelerating the discovery of bioactive specialized metabolites:

Mass Spectrometry Advances: Modern UHPLC-MS systems with high resolution and sensitivity enable comprehensive metabolite profiling from limited plant material [44].

In Silico Annotation Tools: Deep learning approaches for predicting compound classes from MS/MS data are overcoming the bottleneck of metabolite identification [44].

Gene Editing Technologies: CRISPR-based approaches allow precise manipulation of biosynthetic pathways to enhance production of desired compounds or elucidate pathway architecture [39].

The transition in terminology from "secondary" to "specialized" metabolites represents far more than linguistic preference—it embodies an evolution in our understanding of plant chemical ecology and its applications in drug discovery. This conceptual shift acknowledges the sophisticated ecological functions of these compounds while aligning with contemporary research approaches that integrate multi-omics technologies, metabolic engineering, and ecological insights.

For researchers focused on bioactive compound discovery, the specialized metabolism paradigm offers a more accurate framework for understanding the chemical diversity and biological relevance of plant natural products. This perspective, coupled with advanced analytical and computational methods, is accelerating the identification and sustainable production of valuable specialized metabolites with pharmaceutical applications.

As research continues to blur the historical boundaries between primary and specialized metabolism, the field is moving toward a more integrated understanding of plant metabolic networks as dynamic systems continuously evolving to optimize plant survival and adaptation—a rich source of structural diversity for addressing human health challenges.

Advanced Techniques for Extraction, Analysis, and Therapeutic Application