Extraction Techniques for Plant-Based Drug Discovery: A Comparative Analysis of Efficacy and Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of conventional and advanced extraction techniques for isolating bioactive compounds from plants, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Extraction Techniques for Plant-Based Drug Discovery: A Comparative Analysis of Efficacy and Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of conventional and advanced extraction techniques for isolating bioactive compounds from plants, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental principles of extraction, details the mechanisms and applications of modern methods like MAE, UAE, and SFE, and addresses key challenges in process optimization and standardization. By presenting a comparative framework for validating extraction efficacy based on phytochemical yield and bioactivity, this review serves as a strategic guide for selecting and optimizing extraction protocols to enhance the discovery and development of plant-derived pharmaceuticals.

The Foundation of Phytochemical Extraction: Principles and Traditional Techniques

Plant extracts and absolutes represent concentrated forms of the bioactive compounds found in various plant organs and tissues, including flowers, leaves, and fruits [1]. These complex mixtures serve as vital precursors for pharmaceutical development and therapeutic applications, possessing a rich profile of biologically active compounds [1]. The fundamental distinction lies in their processing: plant extracts are thick, paste-like liquids obtained through initial solvent extraction, while absolutes are highly concentrated, purified aromatic liquids obtained through further processing of extracts using high-purity ethanol [1] [2]. In the fragrance industry, absolutes are particularly prized for their intricate and superior aroma profiles that often surpass the original plant's scent [1] [2].

The transition of these botanical preparations from raw plant material to therapeutic agents hinges critically on the extraction methodology employed. The quality, composition, and ultimate efficacy of the final product are profoundly influenced by extraction techniques, which directly impact the yield, richness of ingredients, and preservation of bioactive compounds [1] [2]. Within pharmaceutical research and drug development, understanding these extraction processes is paramount for standardizing bioactive compounds and ensuring reproducible therapeutic effects, forming the foundation for evidence-based herbal therapeutics and modern drug discovery pipelines [3] [4].

Extraction Technologies: Principles and Methodologies

Conventional Extraction Techniques

Conventional extraction methods have formed the historical backbone of plant compound isolation, relying primarily on organic solvents and basic physical processes to liberate bioactive constituents from plant matrices [1] [2].

Maceration involves immersing plant material in volatile organic solvents (e.g., petroleum ether, ethanol) to facilitate mass transfer of compounds through various solvent, temperature, and stirring combinations [1] [2]. The solvent is subsequently recovered via vacuum distillation, yielding a pasty extract [1]. This method offers advantages of operational simplicity and high extraction rates, with solvent selectivity enabling targeted component extraction [1]. However, it is often time-consuming and employs large volumes of potentially toxic solvents, raising safety concerns for both production workers and end consumers [1] [2].

Percolation represents a dynamic leaching advancement over maceration, continuously adding fresh solvent to maintain concentration gradients and improve extraction efficiency, albeit with increased solvent consumption [1] [2]. This technique is particularly suited for valuable, toxic compounds or high-concentration preparations [1].

Reflux extraction utilizes a condenser system to repeatedly heat and recycle volatile solvents until complete component extraction is achieved [1] [2]. While preventing solvent volatilization loss and reducing toxic emissions, this method exhibits limited efficiency for non-volatile active ingredients and can degrade thermally unstable components through prolonged heating [1].

Soxhlet extraction employs solvent reflux and siphoning principles to enable continuous solid compound extraction [1] [2]. Fresh solvent continuously percolates through the plant material, improving mass transfer and ensuring thermal exposure [1]. Despite advantages of low cost and operational simplicity for multiple samples, limitations include lengthy extraction times, potential degradation of heat-sensitive compounds, and substantial use of toxic organic solvents [1] [2].

Table 1: Comparison of Conventional Extraction Techniques

| Extraction Method | Principles | Advantages | Disadvantages | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maceration | Solvent immersion with mass transfer via diffusion | Simple equipment, high extraction rate, solvent selectivity | Time-consuming, large solvent volumes, toxic residues | Violet absolute, Osmanthus absolute [1] |

| Percolation | Continuous solvent flow maintaining concentration gradient | Improved efficiency over maceration | High solvent consumption | Belladonna extracts, Polygala extracts [1] |

| Reflux Extraction | Heated solvent recycling with condenser | Prevents solvent loss, reduces toxic emissions | Low efficiency for non-volatiles, thermal degradation | Flavonoids, saponins [1] |

| Soxhlet Extraction | Continuous extraction via solvent reflux and siphoning | Fresh solvent flow, thermal effect, multiple sample capability | Long extraction time, compound degradation, toxic solvents | Siraitia grosvenorii extract, mulberry leaf extract [1] |

Green Extraction Technologies

Growing environmental and safety concerns regarding conventional methods have spurred development of green extraction technologies that reduce organic solvent use, shorten processing times, and improve extraction efficiency through auxiliary energy inputs [1] [2].

Microwave-assisted extraction (MAE) utilizes electromagnetic radiation to generate intense internal heating within plant cells, rapidly disrupting cellular structures and enhancing compound release into solvents [5]. MAE significantly reduces extraction time and solvent consumption while improving yields, particularly for heat-stable compounds [5].

Ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) employs high-frequency sound waves to create cavitation bubbles near plant cell walls, generating intense localized pressure and temperature that disrupt cellular membranes and facilitate solvent penetration [5]. This method operates at lower temperatures, preserving thermolabile compounds while improving extraction kinetics and efficiency [5].

Supercritical fluid extraction (SFE), particularly using carbon dioxide (CO₂), exploits the unique properties of fluids at temperatures and pressures above critical points [1] [6]. Supercritical CO₂ exhibits gas-like penetration and liquid-like solvation capabilities, enabling highly efficient compound extraction [6]. The process is tunable—lower pressures yield extracts resembling essential oils, while higher pressures extract thicker, waxier constituents containing lipids and pigments [6]. SFE offers significant advantages including minimal thermal degradation, complete solvent removal, and environmental friendliness [6].

Pressurized liquid extraction (PLE), also known as accelerated solvent extraction, utilizes conventional solvents at elevated temperatures and pressures to maintain solvents in liquid states above their normal boiling points [5]. This enhances solubility and mass transfer rates while reducing solvent consumption and extraction times compared to conventional methods [5].

Table 2: Comparison of Green Extraction Technologies

| Extraction Method | Principles | Advantages | Disadvantages | Output Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) | Cellular disruption via electromagnetic heating | Rapid extraction, reduced solvent, improved yields | Potential thermal degradation | Varies by plant material and parameters |

| Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) | Cavitation-induced cell wall disruption | Low temperature, preserved thermolabile compounds | Scale-up challenges | Higher quality heat-sensitive compounds |

| Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) | Solvation using supercritical CO₂ | No solvent residues, tunable selectivity, low temperature | High capital cost, pressure limitations | "Select" extracts (95% essential oil) or "Total" extracts (3-50% essential oil) [6] |

| Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE) | Elevated temperature/pressure solvent extraction | Reduced solvent use, faster extraction | High equipment cost | Similar to conventional solvents but richer |

Comparative Experimental Data: Extraction Efficacy and Therapeutic Potential

Extraction Performance Metrics

Recent comparative studies provide quantitative insights into the performance of various extraction methods. In antimicrobial research, Hibiscus sabdariffa anthocyanin extracts obtained through solvent extraction demonstrated significant bioactivity, with minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) of 125 µg/mL against multidrug-resistant strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus, alongside potent antibiofilm activity at sub-inhibitory concentrations [7]. Furthermore, these extracts exhibited selective cytotoxicity against MCF-7 breast cancer cells, revealing their multifaceted therapeutic potential [7].

The superiority of green extraction methods is evident in efficiency metrics. Supercritical CO₂ extraction typically achieves extraction yields 20-30% higher than conventional Soxhlet extraction while reducing processing time by up to 50% and eliminating organic solvent residues [6]. Similarly, microwave-assisted extraction has demonstrated 20-40% reductions in extraction time and 30-50% decreases in solvent consumption compared to traditional maceration for various medicinal plants [5].

Table 3: Experimental Bioactivity Data for Plant Extracts

| Plant Material | Extraction Method | Bioactivity Results | Experimental Model | Key Active Compounds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hibiscus sabdariffa | Acidified ethanol extraction | MIC: 125 µg/mL vs. MDR bacteria; Significant antibiofilm activity; Selective cytotoxicity to MCF-7 cells | Multidrug-resistant bacterial strains; MCF-7 breast cancer cell line | Anthocyanin glucosides, cyanidin-3-O-glucoside [7] |

| Spiraea species | Dry extract (solvent not specified) | Pronounced antioxidant effect; Reduced viral cytopathic effect | Influenza A virus-infected cells | Flavonoids [8] |

| Ruellia tuberosa | Hydroethanolic extraction | Antiviral activity against H1N1; Reduced infectious viral particles | H1N1 influenza virus | Quercetin, hesperetin, rutin [8] |

| Angelica dahurica | Ethanolic extraction followed by bio-guided fractionation | Inhibition of H1N1 and H9N2 infection/replication; NA and NP synthesis suppression | H1N1 and H9N2 influenza viruses | Furanocoumarins (isoimperatorin, oxypeucedanin) [8] |

Experimental Protocols for Therapeutic Assessment

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: The agar well diffusion method is employed for initial antimicrobial screening [7]. Bacterial/fungal cultures are adjusted to 0.5 McFarland standard, uniformly spread on Mueller-Hinton agar (bacteria) or Sabouraud dextrose agar (fungi), and 6mm wells are aseptically punched into the agar [7]. Wells are loaded with 100µL of pigment extract, with controls receiving solvent alone (negative) or standard antimicrobials (positive) [7]. Plates are incubated at 37°C for 24h (bacteria) or 28°C for 48h (fungi), after which inhibition zone diameters are measured in millimeters [7].

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Determination: The broth microdilution method is used to determine MIC values [7]. Extracts are serially diluted in appropriate broth media, inoculated with standardized microbial suspensions, and incubated under optimal conditions [7]. The MIC is defined as the lowest concentration showing no visible growth, with aliquots subcultured on agar plates to determine minimum microbiocidal concentrations (MMC) [7].

Gene Expression Analysis: Sub-inhibitory concentrations of extracts are applied to microbial cultures to assess virulence gene modulation [7]. RNA is extracted, reverse-transcribed to cDNA, and quantitative PCR performed with specific primers for target genes (e.g., bacterial virulence factors, aflatoxin genes) [7]. Expression levels are normalized to housekeeping genes and compared to untreated controls [7].

Molecular Docking Studies: To elucidate mechanism of action, identified bioactive compounds are computationally docked against relevant microbial targets [7]. For example, cyanidin-3-O-glucoside from H. sabdariffa has been docked with E. coli outer membrane protein A (OmpA) to predict binding interactions that may explain antiadhesive and antimicrobial effects [7].

Analytical Framework and Research Applications

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Materials for Plant Extract Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Solvent Systems | Extraction of different compound classes | Petroleum ether (non-polar), Ethanol (polar/non-polar), Hexane (non-polar), Water (polar) [1] |

| Chromatography Standards | Compound identification and quantification | Cyanidin 3-glucoside (anthocyanins), Quercetin (flavonoids), Berberine (alkaloids) [7] [8] |

| Cell Culture Models | Cytotoxicity and therapeutic assessment | MCF-7 (breast cancer), Vero cells (antiviral), RAW 264.7 (anti-inflammatory) [7] |

| Microbial Strains | Antimicrobial activity screening | ESKAPE pathogens, Candida albicans, Aspergillus flavus [7] |

| Molecular Biology Kits | Gene expression analysis | RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, qPCR kits for virulence genes [7] |

Technological Workflow and Pathway Analysis

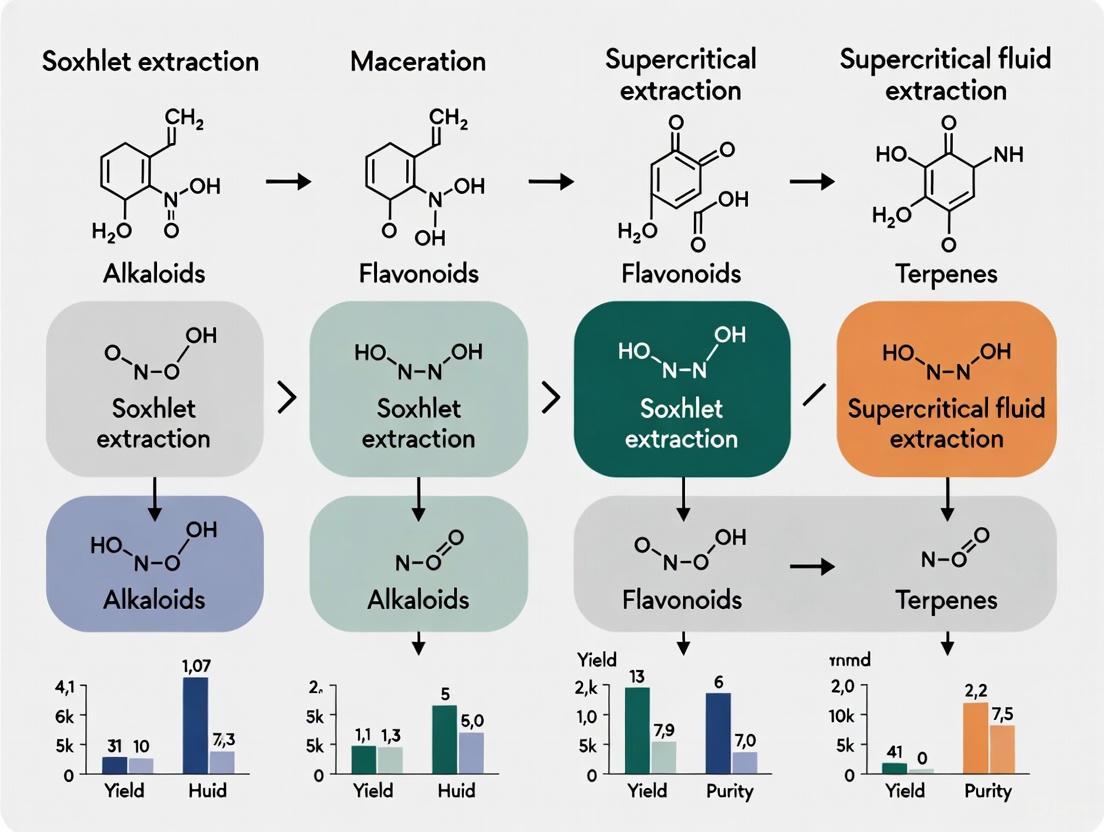

The comprehensive evaluation of plant extracts and absolutes follows an integrated technological pathway from raw material to therapeutic validation, as illustrated in the following workflow:

Diagram 1: Integrated Workflow for Plant Extract Therapeutic Development

The mechanistic pathway through which plant extracts exert antimicrobial effects involves multiple targets and modes of action, particularly relevant for multidrug-resistant pathogens:

Diagram 2: Multimodal Antimicrobial Mechanisms of Plant Extracts

The methodical comparison of extraction technologies reveals a clear trajectory toward green extraction methods that offer enhanced efficiency, reduced environmental impact, and superior preservation of bioactive compounds. While conventional techniques like maceration and Soxhlet extraction continue to provide foundational approaches, technologies including supercritical fluid extraction, microwave-assisted extraction, and ultrasound-assisted extraction demonstrate measurable advantages in yield, selectivity, and operational safety [1] [2] [5].

The therapeutic efficacy of plant extracts and absolutes is fundamentally governed by their extraction methodology, which determines the specific profile of bioactive compounds and consequent pharmacological activities [7] [8]. As pharmaceutical research increasingly turns to natural products for addressing antimicrobial resistance and complex chronic diseases, optimized extraction protocols will play an indispensable role in standardizing bioactive compounds and ensuring reproducible therapeutic effects [3] [4].

Future developments in this field will likely focus on hybrid approaches that combine multiple extraction technologies, computational modeling for method optimization, and advanced delivery systems to enhance bioavailability of therapeutic compounds [4]. Through continued refinement of extraction methodologies and comprehensive biological evaluation, plant extracts and absolutes will remain indispensable resources for drug discovery and development pipelines, effectively bridging traditional knowledge and modern therapeutic science.

The efficacy of any plant extraction technique, from conventional maceration to advanced supercritical fluid extraction, is governed by three fundamental physical principles: solubility, diffusion, and mass transfer [9]. These core principles dictate the rate, yield, and selectivity with which bioactive compounds are recovered from plant matrices, ultimately determining the economic viability and functional performance of the resulting extracts [10]. In pharmaceutical and nutraceutical development, where batch-to-batch consistency and bioactive preservation are paramount, understanding and controlling these principles becomes critical [10].

Solubility determines which compounds will dissolve in a given solvent based on the "like dissolves like" principle, where solvents with polarity values near that of the target solute generally perform better [9]. Diffusion governs the movement of dissolved solutes from the plant interior to the surrounding solvent, a process enhanced by reduced particle size and increased temperature [9]. Mass transfer encompasses the overall movement of solutes from the solid plant matrix into the solvent, influenced by factors such as concentration gradients, temperature, pressure, and mechanical forces applied [10] [11]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of how different extraction technologies manipulate these core principles to optimize performance for specific research and development applications.

Core Principles and Their Role in Extraction Techniques

The Triad of Fundamental Principles

The extraction process progresses through several stages that directly relate to these core principles: (1) solvent penetration into the solid matrix; (2) solute dissolution in the solvent; (3) solute diffusion out of the solid matrix; and (4) collection of extracted solutes [9]. Any factor that enhances diffusivity and solubility improves extraction efficiency.

Table 1: Fundamental Principles Governing Extraction Processes

| Principle | Role in Extraction Process | Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Solubility | Determines dissolution of target compounds in the extraction solvent [9]. | Solvent polarity, temperature, pH, molecular structure of solute [10]. |

| Diffusion | Governs movement of dissolved compounds through plant matrix to solvent [9]. | Temperature, particle size, concentration gradient, plant cell structure [9]. |

| Mass Transfer | Controls overall movement of solutes from solid to liquid phase [11]. | Solvent-to-solid ratio, agitation, temperature, pressure, extraction duration [9] [11]. |

Visualizing the Integrated Extraction Process

The following diagram illustrates how solubility, diffusion, and mass transfer interact sequentially and simultaneously during the extraction of bioactive compounds from plant material.

Comparative Analysis of Extraction Technologies

Conventional Extraction Techniques

Conventional techniques rely primarily on passive diffusion and extended contact time to facilitate mass transfer, often resulting in lengthy processes with potential degradation of heat-sensitive compounds [2] [9].

Maceration involves immersing plant material in solvent for extended periods, with mass transfer driven mainly by concentration gradients without additional energy input [9]. This method is simple but suffers from low efficiency and incomplete extraction [12]. Percolation improves upon maceration by continuously providing fresh solvent, maintaining a higher concentration gradient for enhanced mass transfer [2]. Soxhlet extraction employs a continuous cycling process where solvent is repeatedly evaporated and condensed, constantly exposing plant material to fresh solvent and maintaining a favorable concentration gradient for diffusion [2] [9]. While efficient, the prolonged heating can degrade thermolabile compounds [12].

Table 2: Conventional Extraction Techniques: Mechanisms and Limitations

| Technique | Mechanism | Impact on Core Principles | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maceration [9] | Passive immersion in solvent. | Relies solely on natural diffusion; limited mass transfer. | Long extraction times, low efficiency, incomplete extraction [12]. |

| Percolation [2] | Continuous solvent flow through matrix. | Maintains concentration gradient for diffusion. | High solvent consumption, channeling effects [2]. |

| Soxhlet Extraction [2] [9] | Continuous reflux and solvent renewal. | Constant fresh solvent maximizes mass transfer driving force. | High temperatures degrade thermolabile compounds [10] [12]. |

| Reflux Extraction [2] | Heated solvent with condensation return. | Heat increases solubility and diffusion rates. | Limited to volatile solvents, thermal degradation risk [2]. |

Advanced Extraction Techniques

Modern extraction technologies enhance the core principles by applying external energy or alternative solvents to dramatically improve mass transfer rates and selectivity [10] [13].

Microwave-assisted extraction (MAE) uses electromagnetic radiation to create internal heating within the plant matrix, rapidly increasing pressure that ruptures cell walls and enhances solubility and diffusion [14]. Studies on Matthiola ovatifolia demonstrate MAE's effectiveness, yielding the highest concentrations of total phenolics (69.6 mg GAE/g), flavonoids (44.5 mg QE/g), and alkaloids (71.6 mg AE/g) compared to other methods [14]. Ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) employs acoustic cavitation where bubble formation and implosion generate microjets that disrupt cell walls, significantly improving solvent penetration and mass transfer [10] [15]. Research shows UAE can improve overall metabolite recovery by approximately three times compared to conventional extraction [15].

Supercritical fluid extraction (SFE), typically using CO₂, exploits the tunable solubility and gas-like diffusion properties of supercritical fluids to achieve superior mass transfer characteristics [2] [13]. Pressurized liquid extraction (PLE) uses high pressure to maintain solvents in liquid state at temperatures above their boiling points, dramatically enhancing solubility and diffusion rates while reducing solvent consumption [2] [13].

Table 3: Advanced Extraction Techniques: Enhancements and Efficacy

| Technique | Enhancement Mechanism | Impact on Efficacy | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) [14] | Internal heating and pressure rupture cell walls. | Dramatically improved solubility and diffusion. | Highest yields of phenolics, flavonoids, and alkaloids from M. ovatifolia [14]. |

| Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) [10] [15] | Cavitation disrupts cell structure for better penetration. | Significantly enhanced mass transfer. | 3x higher metabolite recovery vs. conventional methods [15]. |

| Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) [2] [13] | Gas-like diffusion with liquid-like solubility. | Superior mass transfer, tunable selectivity. | High selectivity for lipophilic compounds; preserves thermolabile bioactives [13]. |

| Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE) [2] [13] | High temperature/pressure enhance solubility. | Rapid, efficient extraction with less solvent. | Similar recovery as 2h boiling achieved in <20 minutes [15]. |

Visualizing Technique Selection Logic

The following flowchart provides a logical framework for selecting appropriate extraction technologies based on target compound characteristics and research objectives.

Experimental Protocols and Comparative Data

Standardized Experimental Methodology

To objectively compare extraction techniques, researchers typically follow standardized protocols. The following methodology for comparing MAE, UAE, and conventional solvent extraction (CSE) has been adapted from multiple studies [14] [15]:

Plant Material Preparation: Aerial parts of plant material are collected, rinsed, shade-dried, and lyophilized at -50°C for 48 hours. The lyophilized material is ground to a fine powder (particle size <500 µm) using an electric grinder and stored in airtight containers at -20°C until use [14].

Extraction Procedures:

- Conventional Solvent Extraction (CSE): 1g of plant powder is combined with 30mL of solvent (e.g., 70% ethanol) and subjected to magnetic stirring in the dark for 1 hour. The supernatant is separated by centrifugation at 10,000×g for 10 minutes at 4°C [15].

- Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE): 1g of plant powder is mixed with 30mL of solvent and extracted for 165 seconds at a microwave power level of 550W. The resulting mixture is centrifuged under the same conditions as CSE [14].

- Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE): 1g of plant powder is mixed with 30mL of solvent and sonicated for 15 minutes at an ultrasonic power of 250W. The extract is then centrifuged following the same protocol [15].

Extract Concentration: All collected supernatants are concentrated at 40°C using a rotary evaporator and stored at -18°C for subsequent analysis [15].

Analysis: Total phenolic content is quantified using the Folin-Ciocalteu method with gallic acid as standard. Total flavonoid content is determined using aluminum chloride colorimetric assay with quercetin as standard. Bioactive compounds are identified and quantified using UHPLC-HRMS [14] [15].

Quantitative Comparison of Extraction Yields

The table below summarizes comparative experimental data from multiple studies demonstrating the significant differences in extraction efficiency across techniques.

Table 4: Comparative Extraction Efficiency Across Techniques

| Plant Material | Extraction Method | Key Compound/Class | Yield | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matthiola ovatifolia | MAE (Ethanol) | Total Phenolics | 69.6 ± 0.3 mg GAE/g | [14] |

| Matthiola ovatifolia | MAE (Ethanol) | Total Flavonoids | 44.5 ± 0.1 mg QE/g | [14] |

| Matthiola ovatifolia | MAE (Ethanol) | Total Alkaloids | 71.6 ± 0.2 mg AE/g | [14] |

| Sideritis spp. | UAE (70% Ethanol) | Overall Metabolites | ~3x higher vs. CSE | [15] |

| Sideritis spp. | CSE (70% Ethanol) | Overall Metabolites | Baseline | [15] |

| Moringa oleifera | Maceration | Gallic Acid | Most efficient | [12] |

| Moringa oleifera | Soxhlet | Kaempferol | Most efficient | [12] |

| Moringa oleifera | UAE | Quercetin | Highest yield | [12] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 5: Essential Reagents and Materials for Extraction Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Extraction Research | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ethanol-Water Mixtures [15] | Versatile extraction solvent for wide polarity range. | 70% ethanol often optimal for diverse phytochemicals [15]. |

| Supercritical CO₂ [13] | Green solvent for non-polar compounds; tunable solubility. | Requires specialized equipment; modifiers (e.g., ethanol) expand polarity range [13]. |

| Methanol [10] | Efficient solvent for polar compounds in analytical prep. | Toxicity limits use in food/pharma products [13]. |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) [2] | Green, tunable solvents with low toxicity. | Emerging alternative; can be tailored for specific compound classes [2]. |

| Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent [14] | Quantifies total phenolic content via colorimetric assay. | Standardized against gallic acid equivalents (GAE) [14]. |

| Aluminum Chloride [14] | Quantifies total flavonoid content via complex formation. | Standardized against quercetin equivalents (QE) [14]. |

The comparative efficacy of plant extraction techniques is fundamentally governed by how each technology manipulates the core principles of solubility, diffusion, and mass transfer. Conventional methods like maceration and Soxhlet extraction rely on passive processes and extended contact times, while advanced technologies like MAE, UAE, and SFE actively enhance these principles through external energy input or novel solvent systems [2] [10] [14]. The selection of an appropriate extraction method must consider the target compound's characteristics, the desired throughput, and the sensitivity to thermal degradation. As research advances, hybrid approaches that combine multiple technologies show promise in further optimizing extraction efficiency while aligning with green chemistry principles through reduced solvent consumption and energy requirements [10] [13].

In the pursuit of isolating bioactive compounds from plants, solvent-based extraction remains a cornerstone of natural product research. Among the various techniques, maceration and percolation represent two fundamental, low-tech methods with enduring relevance in scientific and industrial applications [16] [17]. These techniques are particularly valued for their simplicity, minimal equipment requirements, and effectiveness, especially in the initial stages of drug discovery and phytochemical analysis [5]. Understanding their comparative efficacy, grounded in experimental data, is crucial for researchers and development professionals in selecting the optimal method for specific compounds and objectives. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two established methods, framing them within the broader context of extraction technique research.

Principles and Mechanisms at a Glance

The core difference between maceration and percolation lies in the dynamics of the solvent flow, which directly impacts extraction efficiency and speed.

Diagram 1: Mechanism of maceration vs. percolation. Percolation maintains a concentration gradient for higher yield.

Direct Comparative Analysis: Key Experimental Data

A direct, controlled study comparing the extraction of cannabidiol (CBD) from hemp provides robust quantitative data on the performance of these two methods [16].

Table 1: Experimental Comparison of Total CBD Yield [16]

| Extraction Parameter | Maceration (2 weeks) | Percolation |

|---|---|---|

| Average CBD Recovery | 63.52% | 80.10% |

| Relative Improvement | (Baseline) | 16.59% superior (p = 4.419 × 10⁻⁹) |

| Precision (% RSD) | 5% | 2.95% |

| Solvent Recovery (after pressing) | 70.26% | 75.19% |

The data demonstrates that percolation is significantly superior to maceration in total CBD yield. The higher precision (% RSD) of percolation also indicates it is a more consistent and reliable method [16]. This performance advantage is attributed to the continuous supply of fresh solvent in percolation, which maintains a high concentration gradient—the driving force for mass transfer—thereively leaching compounds from the plant matrix [16] [2].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear framework for researchers, the following details the core methodologies cited in the comparative data.

- Plant Material Preparation: The raw plant material (e.g., hemp biomass) is comminuted (finely ground) to increase the surface area for solvent contact.

- Mixing: The comminuted material is mixed with a specific volume of extraction solvent (e.g., 95% ethanol, chosen for lipophilic compounds like CBD) in a sealed container.

- Soaking: The mixture is allowed to stand at room temperature, with occasional agitation, for a defined period (e.g., 2 weeks).

- Separation: After the set time, the liquid portion (the miscella) is drained from the solid residue (the marc).

- Pressing (Optional): The marc is pressed to recover any trapped solvent containing solutes, which is then combined with the initially drained liquid.

- Apparatus Setup: A percolator (a conical vessel with an outlet at the bottom) is set up.

- Packing: The comminuted plant material is packed into the percolator.

- Solvent Addition: The extraction solvent (e.g., 95% ethanol) is continuously added to the top of the percolator, allowing it to percolate (trickle) down through the plant material bed by gravity.

- Collection: The extract solution is collected continuously from the outlet at the bottom. Fresh solvent is added to maintain a constant solvent level, ensuring continuous extraction and a sustained concentration gradient.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful extraction relies on the appropriate selection of materials and solvents based on the target compounds' chemical properties.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Solvent Extraction

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| 95% Ethanol | A common, versatile solvent for extracting a wide range of polar and mid-polarity compounds (e.g., cannabinoids, phenolics). Its concentration is optimal for lipophilic compounds [16] [17]. |

| Comminuted Plant Biomass | The starting plant material (e.g., hemp, sage) must be properly ground to increase surface area and enhance mass transfer of target compounds into the solvent [16] [18]. |

| Percolator | A specialized vessel, typically conical, that holds the plant biomass and allows for the controlled, continuous flow of solvent through the solid bed [16] [2]. |

| Hydroethanolic Solvents | Mixtures of water and ethanol in varying ratios. Adjusting the ratio allows fine-tuning of solvent polarity to selectively extract different classes of bioactive molecules [16] [19]. |

| Olive Oil | A non-toxic, green solvent used in oleolites for extracting lipophilic compounds. It can offer superior stability for sensitive metabolites compared to alcoholic tinctures [19]. |

Within the broad thesis of comparing plant extraction techniques, this analysis solidifies the roles of both maceration and percolation. Maceration remains a valuable, straightforward technique for small-scale or preliminary extractions where simplicity is paramount. However, experimental evidence clearly establishes percolation as the superior traditional method for efficiency and yield of lipophilic compounds like CBD, with a 16.59% higher recovery rate and greater precision [16]. The principle of maintaining a concentration gradient via continuous solvent flow is a fundamental advantage that also informs modern, enhanced techniques like Soxhlet extraction [2] [1].

While newer, green technologies offer benefits in speed and sustainability [5] [20], the simplicity, low cost, and proven effectiveness of maceration and percolation ensure their continued relevance. They serve as a critical baseline against which novel methods are measured and remain indispensable tools in the researcher's arsenal for natural product extraction and drug development.

The extraction of bioactive compounds from plant matrices is a foundational step in pharmaceutical, nutraceutical, and cosmetic research and development. Among the various techniques available, Soxhlet and Reflux extraction have endured as standard conventional methods due to their operational simplicity and proven effectiveness. Both techniques leverage thermal energy to enhance the mass transfer of compounds from solid plant material into a solvent, yet they employ distinct mechanical principles to achieve this goal [1]. The sustained application of heat in these methods serves to increase the solubility of target analytes, reduce solvent viscosity, and improve diffusion rates, thereby accelerating the extraction process. However, the specific implementation of thermal energy differs significantly between the two, leading to variations in efficiency, suitability for different compound classes, and overall impact on the extracted phytochemical profile [21].

Within the broader context of plant extraction technique research, understanding the nuanced performance characteristics of Soxhlet and Reflux extraction is critical for selecting the appropriate method for a given application. While modern green techniques like microwave-assisted and ultrasound-assisted extraction offer advantages in speed and solvent consumption, Soxhlet and Reflux remain widely used, particularly as benchmark methods for evaluating newer technologies [1] [22]. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of these two classical techniques, supported by experimental data and methodological protocols, to aid researchers and drug development professionals in making informed decisions for their extraction workflows.

Principles and Methodologies

Soxhlet Extraction

The Soxhlet extractor, designed in 1879, operates on a principle of continuous, cyclic solvent recycling driven by thermal energy. The apparatus consists of three main components: a flask containing the boiling solvent, an extraction chamber housing the solid sample in a porous thimble, and a condenser for cooling solvent vapors [23] [22]. The process begins with heating the flask, causing solvent evaporation. The vapor travels upward through the apparatus to the condenser, where it liquefies and drips onto the solid sample in the thimble. As the extraction chamber fills, the solvent extracts the desired compounds through repeated contact. Once the liquid level reaches the top of the siphon arm, the solution—now enriched with extracted compounds—is siphoned back into the flask. This cycle repeats automatically dozens or even hundreds of times, ensuring the sample is continuously exposed to fresh, pure solvent, which maintains a high concentration gradient and drives the extraction toward completion [22].

A key characteristic of standard Soxhlet extraction is that the sample itself is not heated directly by an external source but is instead contacted by warm solvent that has just condensed from the vapor phase. This means the extraction occurs at a temperature roughly equivalent to the boiling point of the solvent, but the plant matrix is not subjected to the potentially higher temperature at the bottom of the solvent flask [23]. This process is considered an exhaustive extraction method, as it continues until the target compounds are completely removed from the solid matrix, which is why it is often used as a reference method for evaluating the efficiency of other extraction techniques [22].

Reflux Extraction

Reflux extraction, specifically Heat Reflux Extraction (HRE), employs a different approach by maintaining the solvent at its boiling point throughout the process in a system designed to prevent solvent loss. In a typical HRE setup, the sample is immersed directly in the boiling solvent within a flask equipped with a vertical condenser [24] [25]. The solvent is heated to its boiling point, generating vapor that rises into the condenser. The condenser cools the vapor, causing it to liquefy and drip back into the flask. This continuous evaporation and condensation cycle prevents solvent loss, even during extended extraction times, and allows the system to maintain a constant volume of boiling solvent in contact with the sample [1] [24].

The primary mechanism enhancing extraction efficiency in HRE is the continuous application of high temperature. The direct contact between the plant matrix and the boiling solvent accelerates the dissolution of compounds, disrupts plant cell walls, and increases the diffusion coefficient of the target analytes [25]. Unlike the Soxhlet method, where the sample is extracted by percolating condensed solvent, the sample in HRE is fully submerged and agitated by the boiling action, which can improve mass transfer. This method is particularly effective for extracting thermostable compounds and is valued for its ability to process larger sample batches simultaneously, making it suitable for industrial-scale production [25]. However, the constant exposure to high temperatures can be a drawback for heat-labile compounds, which may degrade during the process [1].

Table 1: Core Operational Principles and Setup

| Feature | Soxhlet Extraction | Reflux (Heat Reflux) Extraction |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Continuous cyclic solvent recycling via siphon mechanism | Continuous boiling with solvent vapor condensation and return |

| Extraction Mode | Semi-continuous, sequential | Continuous immersion in boiling solvent |

| Sample Environment | Warm, percolating condensed solvent | Directly submerged in boiling solvent |

| Temperature | Near the boiling point of the solvent | At the boiling point of the solvent |

| Key Driver | Constant renewal of solvent to maintain concentration gradient | High temperature to enhance solubility and diffusion |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key differences in the operational pathways of Soxhlet and Reflux extraction systems.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Efficiency and Yield

The extraction performance of Soxhlet and Reflux methods varies significantly depending on the target compound and the raw material. A direct comparative study extracting endocrine-disrupting chemicals from solid waste dumpsite soil found that Soxhlet extraction demonstrated superior performance for certain compound classes, notably achieving approximately 15% higher extraction efficiency for phthalates compared to reflux extraction [26]. This was attributed to the continuous fresh solvent contact in the Soxhlet system, which maintains a steep concentration gradient favorable for extracting these compounds. However, for other compound types present in the same matrix, the difference in efficiency between the two methods was not statistically significant, indicating that the choice of method should be compound-specific [26].

In applications focused on thermostable compounds, Reflux extraction can achieve high yields. For instance, in the extraction of polyphenols and flavonoids from hempseed threshing residue, an optimized Heat Reflux Extraction (HRE) process achieved a Total Phenolic Content (TPC) yield of 27.54% and a Total Flavonoid Content (TFC) yield of 16.02% [25]. The high temperature and continuous boiling action effectively break down plant cell structures, facilitating the release of intracellular compounds. However, it is crucial to note that while HRE can be highly efficient, its yields for heat-labile substances may be lower than those obtained by methods operating at milder temperatures due to compound degradation [21].

Operational Parameters and Limitations

Both techniques share common limitations inherent to conventional extraction methods, primarily related to their high solvent consumption, lengthy extraction times, and significant energy input [1] [22]. However, their specific operational drawbacks differ.

Soxhlet extraction is notoriously time-consuming, often requiring several hours to dozens of hours to complete the exhaustive extraction process [22]. The sample is also not exposed to the highest temperature of the boiling flask, which can be a limitation for extracting compounds with very high solubility at elevated temperatures [23]. Furthermore, the use of a siphon mechanism leads to an intermittent process, where the boiling in the flask can be disrupted each time the siphoning occurs [23]. Solvent recovery after extraction is also noted as an inconvenient and potentially hazardous step [23].

Reflux extraction, while also lengthy, is generally faster than Soxhlet for achieving a substantial yield in a single batch process [25]. Its most significant drawback is the constant exposure of the sample to boiling solvent, which poses a high risk of thermal degradation for sensitive bioactive compounds such as certain flavonoids, vitamins, and volatile aromatics [1] [21]. This makes Reflux less suitable for a wide range of modern pharmaceutical and nutraceutical applications where preserving the structural integrity of delicate molecules is paramount.

Table 2: Comparative Advantages and Disadvantages

| Aspect | Soxhlet Extraction | Reflux (Heat Reflux) Extraction |

|---|---|---|

| Advantages | - Exhaustive extraction [22]- No filtration required post-extraction [27]- Continuous solvent recycling [23]- Simple, robust apparatus | - Higher temperature enhances mass transfer [25]- Suitable for batch processing and scale-up [25]- Prevents solvent loss [24]- Can achieve high yields for stable compounds [25] |

| Disadvantages | - Very long extraction time [22]- High solvent consumption [1]- Not suitable for thermolabile compounds [21]- Inconvenient solvent recovery [23] | - High risk of thermal degradation [1]- High energy consumption [25]- Limited to thermostable compounds- Can be less selective |

Experimental Protocols and Data

Detailed Experimental Methodology

Protocol for Soxhlet Extraction of β-Carotene from Gac Fruit Peel [27]:

- Raw Material Preparation: Fresh gac fruit peel is washed, sliced into rods (1 × 1 × 6 cm), and dried at 100°C until the moisture content reaches 10-15% (dry basis). The dried peel is ground and sieved to a particle size of < 1 mm.

- Extraction Setup: A known mass of the prepared peel powder is placed in a cellulose thimble. The thimble is loaded into the extraction chamber of a Soxhlet apparatus. A solvent mixture of ethyl acetate and acetone (6:4 v/v) is added to a round-bottom flask, which is attached to the apparatus. A condenser is set up at the top.

- Extraction Process: The solvent is heated using a heating mantle, initiating the cycle of evaporation, condensation, and siphoning. The extraction is typically continued for a predetermined number of cycles or until the solvent in the siphon tube appears colorless.

- Extract Recovery: After extraction, the solvent in the flask, now containing the dissolved β-carotene, is carefully evaporated using a rotary evaporator under reduced pressure to concentrate the extract. The concentration of β-carotene is determined via UV-Vis spectrophotometry at 455 nm.

Protocol for Heat Reflux Extraction of Polyphenols from Hempseed Threshing Residue [25]:

- Optimization Design: The process is optimized using Response Surface Methodology (RSM) with a Box-Behnken Design. Key parameters include extraction time (X1: 30-150 min), liquid-solid proportion (X2: 3:1-7:1 mL/g), particle size (X3: 180-2000 μm), and ethanol concentration (X4: 50-90%).

- Extraction Setup: A specified mass of powdered hempseed residue is placed in a round-bottom flask. A measured volume of ethanol/water solvent at a defined concentration is added to the flask. The flask is fitted to a reflux condenser.

- Extraction Process: The mixture is heated to a gentle boil using a heating mantle or water bath, maintaining the solvent at its boiling point for the duration of the extraction. The condenser ensures all solvent vapors are condensed and returned to the flask.

- Sample Analysis: After extraction, the mixture is cooled, concentrated under reduced pressure, and centrifuged. The supernatant is analyzed for Total Phenolic Content (TPC) using the Folin-Ciocalteu method and Total Flavonoid Content (TFC) using the aluminum chloride colorimetric method.

Quantitative Performance Data

The following table summarizes key performance data for Soxhlet and Reflux extraction from recent experimental studies, highlighting yields, optimal conditions, and model parameters.

Table 3: Experimental Data from Recent Studies

| Extraction Method & Target | Optimal Conditions | Key Performance Metrics | Modeling Insights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soxhlet Extraction of β-Carotene from Gac Fruit Peel [27] | - Solvent: Ethyl Acetate:Acetone (6:4 v/v)- Sample Mass: Positive influence- Solvent Flow Rate: Positive influence | - Yield: Highest with optimized solvent mixture. | A two-stage kinetic model (filling & cycling) was developed. The model estimated an extraction rate constant (kₑ) and a degradation rate constant (k𝒹), providing a valuable tool for process optimization. |

| Heat Reflux Extraction of Polyphenols/Flavonoids from Hempseed Residue [25] | - Time: 69.71 min- Liquid-Solid: 5.12:1 mL/g- Particle Size: 1150 μm- Ethanol: 69.60% | - Crude Extract Yield: 4.74%- Total Phenolic Content (TPC): 27.54%- Total Flavonoid Content (TFC): 16.02%- Showed significant antioxidant and immunomodulatory activity. | The RSM model successfully predicted yields, showing that all four parameters significantly influenced the extraction efficiency of polyphenols and flavonoids. |

| Comparative Study on Soil Contaminants [26] | - Standard Soxhlet and Reflux protocols. | - Soxhlet extraction was ~15% more efficient for phthalates.- For other annotated compounds (e.g., anthracene), the difference was not significant. | Principal Component Analysis (PCA) confirmed the superior extractability of phthalates in Soxhlet, attributing it to the continuous fresh solvent contact. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Materials for Soxhlet and Reflux Extraction

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Soxhlet Apparatus | Standard glassware setup including flask, extraction chamber, and condenser for continuous cyclic extraction [27]. |

| Reflux Condenser Setup | Glassware assembly (flask, condenser) for boiling extractions while preventing solvent loss [25]. |

| Cellulose Extraction Thimbles | Porous containers for holding solid sample powder in Soxhlet extraction, allowing solvent flow [27]. |

| Ethyl Acetate | Low-toxicity, "preferred" solvent for extracting medium-polarity compounds like β-carotene [27]. |

| Acetone | Polar, low-toxicity solvent effective for disrupting plant cell membranes and extracting intracellular compounds [27]. |

| Ethanol (Aqueous) | Versatile, renewable solvent of varying polarity; commonly used for extracting polyphenols and flavonoids [25]. |

| Heating Mantle / Magnetic Hotplate | Provides controlled, uniform heating to the solvent flask for maintaining boiling or evaporation [27] [25]. |

| Rotary Evaporator | Essential for efficient, low-temperature solvent removal and concentration of the final extract post-extraction [22]. |

| Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent | Chemical reagent used in spectrophotometric assay for quantifying total phenolic content (TPC) [25]. |

| Aluminum Chloride (AlCl₃) | Used in colorimetric assay for quantifying total flavonoid content (TFC) [25]. |

Soxhlet and Reflux extraction remain critically important techniques in the researcher's arsenal for the isolation of plant bioactive compounds. The choice between them hinges on the specific requirements of the application. Soxhlet extraction is the method of choice for exhaustive extraction where the continuous renewal of solvent is paramount, and when processing thermostable compounds that can withstand prolonged cyclic heating. Conversely, Reflux extraction offers a powerful, scalable approach for efficiently extracting compounds under constant high-temperature conditions, making it suitable for industrial batch processing, particularly for stable molecules like certain polyphenols.

However, the comparative data also underscores their shared significant limitations, most notably the high solvent and energy consumption, long processing times, and inherent risks to thermolabile compounds. These drawbacks have driven the development and adoption of modern green extraction technologies. Techniques such as Accelerated Solvent Extraction (ASE) have been demonstrated to match the extraction efficiency of Soxhlet while being faster, using significantly less solvent, and offering greater automation and environmental friendliness [28]. Similarly, ultrasound and microwave-assisted methods often provide superior preservation of heat-sensitive bioactives [21]. Therefore, while Soxhlet and Reflux extraction provide foundational efficiency through thermal energy, their role is increasingly that of a benchmark against which the performance of newer, more sustainable technologies is measured in the ongoing research into optimal plant extraction methodologies.

The efficacy of plant extraction techniques is a cornerstone of natural product research, directly influencing the yield, quality, and bioactivity of the resulting extracts [10]. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting an appropriate extraction method is paramount, as this choice dictates the chemical profile of the extract and its potential therapeutic applications [29]. Conventional extraction techniques, including maceration, Soxhlet, percolation, and reflux extraction, have been widely used for decades due to their operational simplicity and equipment accessibility [2] [1]. However, these methods present significant inherent limitations related to extensive processing times, large solvent consumption, and thermal degradation of bioactive compounds [10]. These drawbacks not only affect the economic viability and environmental sustainability of extraction processes but also compromise the quality and bioactivity of the final product, thereby impacting subsequent pharmaceutical development [2]. This guide provides an objective comparison of conventional and modern extraction techniques, supported by experimental data, to inform method selection in research and development contexts.

Fundamental Principles and Limitations of Conventional Extraction

Conventional extraction methods primarily rely on the use of organic solvents and the application of heat to facilitate the mass transfer of phytochemicals from plant matrices into solution [2]. The fundamental mechanisms involve solvent penetration, cellular dissolution, and compound diffusion [1]. Despite their historical prevalence, these techniques are characterized by several critical inefficiencies.

Table 1: Core Conventional Extraction Techniques and Their Limitations

| Method | Principle of Operation | Primary Limitations | Impact on Extract Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maceration | Soaking plant material in solvent at room temperature with agitation [1]. | Very long extraction times (up to 72 hours), large solvent volumes, low efficiency for some compounds [2] [30]. | Potential for solvent residue; risk of microbial growth during long extraction [1]. |

| Soxhlet Extraction | Continuous cycling of fresh solvent through sample via heating and condensation [2] [1]. | High temperatures at solvent boiling point, prolonged extraction (several hours), high solvent use, not suitable for thermolabile compounds [10] [30]. | Thermal degradation of heat-sensitive phytochemicals like some flavonoids and polyphenols [10]. |

| Reflux Extraction | Similar to Soxhlet but sample remains in contact with boiling solvent in a sealed system to prevent solvent loss [2]. | Application of continuous heat, limited to volatile solvents, degradation of thermally unstable components [2]. | Destruction of some non-volatile and thermally unstable active ingredients [2]. |

| Percolation | Continuous flow of fresh solvent through a fixed bed of plant material [2] [1]. | Higher solvent consumption than maceration, can be time-consuming, channeling may reduce efficiency [2]. | Inconsistent extraction if channeling occurs, leading to variable compound yields [2]. |

The limitations of these conventional methods manifest in three critical areas:

- Temporal Inefficiency: Processes like maceration require prolonged contact times, sometimes exceeding 72 hours, to approach equilibrium, creating bottlenecks in research and production workflows [2] [30].

- Solvent-Related Drawbacks: The consumption of large volumes of organic solvents (e.g., hexane, petroleum ether, chloroform) raises significant safety, cost, and environmental concerns [2] [10]. Residual toxic solvents in the final extract also pose a challenge for pharmaceutical applications, potentially requiring extensive purification steps [1].

- Thermal Degradation: Methods involving heating, particularly Soxhlet and reflux extraction, subject phytochemicals to prolonged elevated temperatures [10]. This can lead to the decomposition, hydrolysis, or isomerization of sensitive bioactive compounds such as polyphenols, flavonoids, and terpenoids, thereby diminishing the extract's bioactivity and altering its chemical profile [10].

Quantitative Comparison of Extraction Performance

Experimental studies directly comparing conventional and modern techniques provide compelling data on their relative performance regarding yield, chemical composition, and bioactivity.

Table 2: Experimental Comparison of Extraction Techniques for Mentha longifolia L. [30]

| Extraction Technique | Solvent | Total Phenolic Content (mg GAE/g) | Total Flavonoid Content (mg QE/g) | Antioxidant Activity (IC50 DPPH, µg/mL) | Key Compound (e.g., Rosmarinic Acid) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soxhlet Extraction | 70% Ethanol | High | High | High Potency (Lowest IC50) | Highest Yield |

| Ultrasound-Assisted (UAE) | 70% Ethanol | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate Potency | Moderate Yield |

| Cold Maceration | 70% Ethanol | High | High | High Potency (Similar to Soxhlet) | High Yield |

| Soxhlet Extraction | Ethyl Acetate | Low | Low | Low Potency | Low Yield |

| Ultrasound-Assisted (UAE) | Water | Low | Low | Low Potency | Low Yield |

A separate study on olive leaf extracts further highlighted the efficiency of modern methods. Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE) with 15% glycerol at 70°C yielded extracts with a Total Polyphenol Content of 19.46 mg GAE/g dw and a potent Antioxidant Capacity (IC50) of 4.11 mg/mL [31]. In contrast, conventional Soxhlet extraction required longer times and more solvent to achieve lower yields [31]. The impact of extraction technique on bioactivity is profound. For instance, the higher flavonoid and polyphenol yields achieved by efficient modern methods directly contribute to superior antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial properties [10]. The PLE extract from olive leaves with 15% ethanol at 70°C also showed significant inhibition (70%) of the α-glucosidase enzyme, highlighting its potential for managing type 2 diabetes [31].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear basis for comparison, detailed methodologies for key experiments are outlined below.

Protocol 1: Comparative Evaluation of Soxhlet, UAE, and Maceration

This protocol is adapted from a study on Mentha longifolia L. [30].

- Objective: To compare the efficiency of conventional and modern techniques in extracting phenolic compounds and to assess the resulting antioxidant activity.

- Plant Material: Aerial parts of Mentha longifolia L., dried and mechanically ground to a fine powder.

- Solvents: 70% Ethanol, Ethyl Acetate, Distilled Water.

- Methodologies:

- Soxhlet Extraction: 10 g of plant powder was placed in a Soxhlet apparatus. Extraction was conducted with 250 mL of solvent for 1-4 hours, based on the solvent's boiling point. The extract was filtered, centrifuged, and concentrated under reduced pressure at 40°C [30].

- Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE): 1 g of plant powder was mixed with 20 mL of solvent (1:20 ratio). Extraction was performed in an ultrasonic bath (40 kHz) for 20 minutes at 25°C. The extract was then filtered, centrifuged, and concentrated under reduced pressure at 40°C [30].

- Cold Maceration: 1 g of plant powder was soaked in 20 mL of solvent for 72 consecutive hours at ambient temperature in the dark with continuous shaking. The resulting extract was filtered and concentrated [30].

- Analysis:

- Phytochemical Profile: HPLC-DAD analysis for phenolic compounds like rosmarinic acid, caffeic acid, and quercetin.

- Total Phenolic/Flavonoid Content: Folin-Ciocalteu and Aluminum chloride methods, respectively.

- Antioxidant Activity: DPPH radical scavenging assay.

Protocol 2: Assessment of Pressurized Liquid vs. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction

This protocol is adapted from a study on olive leaves [31].

- Objective: To evaluate the performance of PLE and UAE using green solvents for recovering polyphenols with antioxidant and antihyperglycemic activities.

- Plant Material: Olive leaves (Olea europaea), washed, air-dried, and ground.

- Solvents: Pure water, 15% ethanol, 15% glycerol.

- Methodologies:

- Analysis:

- Total Polyphenol Content: Folin-Ciocalteu method.

- Antioxidant Capacity: DPPH and other relevant assays.

- Enzyme Inhibition: Inhibitory activity against α-amylase and α-glucosidase enzymes.

- Compound Specificity: HPLC analysis to quantify specific polyphenols like oleuropein.

Visualization of Workflow and Impacts

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the choice of extraction methodology and its consequent impacts on the process and final product, as demonstrated by the experimental data.

Extraction Method Impact Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the appropriate reagents and materials is critical for designing effective extraction experiments. The following table details key solutions used in the featured protocols.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Extraction Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Extraction Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Ethanol (70-100%) | A versatile, relatively green solvent effective for extracting a wide range of polar and mid-polarity compounds like phenolics and flavonoids [30] [31]. | Primary solvent in maceration, Soxhlet, and UAE for compounds such as rosmarinic acid in Mentha longifolia [30]. |

| Glycerol-Water Mixtures | A green, non-toxic, and biodegradable solvent that can form hydrogen bonds, effective for recovering various polyphenol classes [31]. | Used in PLE at 70°C to achieve high total polyphenol content from olive leaves [31]. |

| Ethyl Acetate | A semi-polar organic solvent used for selective extraction of medium and low-polarity compounds [30]. | Used in Soxhlet and maceration to extract specific lipid-soluble phytochemicals [30]. |

| DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) | A stable free radical used to evaluate the free radical scavenging (antioxidant) capacity of plant extracts [30]. | Standard assay to measure and compare the antioxidant activity of extracts from different methods/conditions [30]. |

| Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent | A chemical reagent used in colorimetric assays to determine the total phenolic content in plant extracts [30]. | Quantifying the overall yield of phenolic compounds achieved by different extraction techniques [30]. |

| HPLC-DAD Standards | Authentic chemical standards (e.g., oleuropein, rosmarinic acid, quercetin) for compound identification and quantification [30] [31]. | Essential for analyzing the specific phytochemical profile and ensuring the extraction method does not degrade target analytes [30] [31]. |

The empirical data and comparative analysis presented in this guide clearly demonstrate the significant limitations of conventional extraction methods, particularly concerning time consumption, solvent volume, and thermal degradation [2] [10]. While techniques like Soxhlet extraction and maceration can achieve high yields for some stable compounds, their inefficiencies and potential to compromise bioactive compound integrity are major drawbacks for modern pharmaceutical and nutraceutical development [30]. Modern green techniques such as Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) and Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE) offer compelling advantages, including dramatically reduced extraction times, lower solvent consumption, and the preservation of heat-sensitive bioactive compounds through milder operating conditions [10] [31]. For researchers and drug development professionals, the migration towards these advanced, sustainable extraction strategies is not merely a trend but a necessary step to enhance the quality, efficacy, and consistency of plant-based extracts, thereby accelerating the translation of natural products into effective therapeutics.

Advanced and Green Extraction Technologies: Mechanisms and Industrial Applications

Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) has emerged as a leading green extraction technology, offering substantial advantages over conventional methods for recovering bioactive compounds from plant matrices. This comparison guide objectively analyzes MAE's performance against other extraction techniques, focusing on its core principles of volumetric heating and cell disruption. We present synthesized experimental data demonstrating MAE's superior efficiency in terms of extraction yield, time reduction, solvent consumption, and energy utilization across diverse applications in pharmaceutical, food, and cosmetic industries. The integration of advanced optimization strategies and synergistic approaches positions MAE as a cornerstone technology for sustainable extraction processes in research and industrial settings.

The global shift toward sustainable industrial practices has intensified the demand for green extraction technologies to replace conventional methods, which are often inefficient and environmentally burdensome [32]. Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) stands out as a promising alternative that leverages microwave energy to achieve rapid, efficient, and selective recovery of natural compounds [32]. As plant extracts gain importance in drug discovery, nutraceuticals, and functional foods, selecting optimal extraction technology becomes crucial for preserving compound bioactivity, reducing environmental impact, and improving process economics [1] [33].

This guide provides a comprehensive technical comparison of MAE against other extraction technologies, with specific focus on its fundamental operating principles—volumetric heating and cell disruption mechanisms. We present objectively analyzed experimental data from recent research studies, detailed methodological protocols for technology implementation, and analytical frameworks for evaluating extraction efficacy. The content is structured to serve researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to implement or optimize MAE within their experimental workflows and industrial processes.

Fundamental Principles of MAE

Volumetric Heating Mechanism

MAE operates on the principle of volumetric heating, where microwave energy directly interacts with materials through two simultaneous mechanisms: ionic conduction and dipole rotation [34]. This differs fundamentally from conventional heating methods that rely on conduction and convection, which are slower and create thermal gradients from the surface inward.

In dipole rotation, polar molecules (such as water or ethanol) continuously align themselves with the oscillating electric field of microwaves (typically at 2.45 GHz), generating molecular friction and heat throughout the material volume [35]. Simultaneously, ionic conduction occurs where dissolved ions oscillate and migrate in response to the electric field, colliding with neighboring molecules and converting kinetic energy to heat [34]. This dual mechanism enables rapid and uniform temperature increase throughout the entire plant material-solvent system, significantly accelerating the extraction process.

Cell Disruption Process

The efficiency of MAE primarily stems from its ability to disrupt plant cell structures through internal pressure buildup. As the microwave energy interacts with intrinsic moisture and polar compounds within plant cells, instantaneous heating occurs, converting water to steam and creating tremendous internal pressure on cell walls and membranes [35]. This pressure surpasses the cell wall's mechanical strength, leading to rupture and release of intracellular compounds into the surrounding solvent [36].

The cell disruption process in MAE creates synergistic alignment of heat and mass transfer gradients, working in the same direction from the interior of plant cells to the surrounding solvent [35]. This contrasts with conventional extraction where heat transfers from the exterior inward while mass transfer occurs in the opposite direction, creating counterproductive gradients that limit efficiency and prolong extraction times.

Figure 1: MAE Mechanism Pathway: This diagram illustrates the sequential process from microwave energy application to compound release, highlighting the dual heating mechanisms and critical cell disruption step.

Comparative Performance Analysis

MAE vs. Conventional Extraction Methods

Experimental data consistently demonstrates MAE's clear superiority over traditional extraction techniques across multiple performance metrics. The following table synthesizes comparative results from recent studies:

Table 1: MAE vs. Conventional Extraction Methods - Performance Comparison

| Plant Material | Target Compounds | MAE Performance | Conventional Method | Performance Improvement | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stevia leaves | Phenolic compounds, Flavonoids | 5.15 min, 284.05 W, 53.1% ethanol | Ultrasound-assisted extraction | 8.07% higher TPC, 11.34% higher TFC, 58.33% less time | [37] |

| Barleria lupulina Lindl. | Antioxidants, Polyphenols | 30s, 400W, 80% ethanol | Traditional solvent extraction | TPC: 238.71 mg GAE/g, TFC: 58.09 mg QE/g, DPPH: 87.95% | [34] |

| Mandarin peel | Polyphenols, Carotenoids, Pectin | Optimized MAE conditions | Conventional solvent extraction | Higher yields, reduced extraction times, lower energy consumption | [38] |

| Camellia japonica flowers | Phenolic compounds, Flavonols | 180°C, 5 min, 80% yield | Ultrasound-assisted extraction | 24% higher yield than UAE (56%) | [39] |

| Nettle leaves | Polyphenolic compounds | 300W, 10min, NADES solvent | Conventional methods | High antioxidant activity, good antimicrobial potential | [36] |

MAE consistently outperforms conventional methods, particularly in extraction efficiency and time reduction. For instance, MAE of stevia leaves provided 8.07% higher total phenolic content (TPC) and 11.34% higher total flavonoid content (TFC) while requiring 58.33% less extraction time compared to ultrasound-assisted extraction [37]. Similarly, MAE achieved optimal extraction of antioxidants from Barleria lupulina in just 30 seconds – a time reduction of several orders of magnitude compared to traditional methods that often require hours [34].

MAE vs. Other Green Extraction Technologies

When compared against other advanced extraction technologies, MAE maintains competitive advantages in specific applications:

Table 2: MAE vs. Other Green Extraction Technologies

| Extraction Technique | Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations | Optimal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) | Volumetric heating, Cell disruption via internal pressure | Rapid extraction, Reduced solvent use, Higher yields, Selective heating | Equipment cost, Limited scale-up for some systems, Safety concerns with closed vessels | Heat-stable compounds, Polar compounds, Thermally robust matrices |

| Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) | Acoustic cavitation, Cell disruption via bubble collapse | Moderate temperature, Equipment simplicity, Good for labile compounds | Longer extraction times, Possible free radical formation | Labile compounds, Temperature-sensitive materials |

| Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) | Solvation with supercritical fluids (e.g., CO₂) | Clean extracts, No solvent residues, Tunable selectivity | High equipment cost, Pressure limitations, Limited polarity range | Lipophilic compounds, Essential oils, Temperature-sensitive compounds |

| Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE) | Enhanced solubility and mass transfer at high pressure/temperature | High throughput, Automation compatible, Good reproducibility | High equipment cost, Thermal degradation risk | Wide range of compounds, Automated sequential extraction |

Comparative analysis reveals that MAE provides either higher yields, reduced extraction times, or both compared to conventional solvent extraction, depending on the target compound [38]. The technology is particularly effective for extracting thermostable compounds where rapid heating does not compromise bioactivity. MAE's integration with other green technologies, such as its combination with ultrasound or environmentally friendly solvents, further enhances its application scope and efficiency [32].

Experimental Protocols and Optimization

Standard MAE Experimental Workflow

A generalized MAE protocol can be adapted for various plant materials and target compounds with parameter optimization:

Figure 2: MAE Experimental Workflow: This diagram outlines the standard procedural sequence from sample preparation through to bioactivity assessment, highlighting key optimization and analytical stages.

Sample Preparation: Plant materials should be dried (typically at 50±5°C for 5 hours), ground to a fine powder (40-60 mesh size), and stored in airtight containers to prevent moisture absorption [36]. Uniform particle size ensures consistent microwave interaction.

Solvent Selection: Choose solvents based on compound polarity and microwave absorption properties:

Parameter Optimization: Critical MAE parameters requiring optimization:

- Microwave power (200-1000W): Higher power increases heating rate but risks compound degradation [34]

- Extraction time (30s-30min): Shorter times (seconds to minutes) typically sufficient [34]

- Temperature (50-180°C): Optimized based on compound stability [39]

- Solvent-to-sample ratio (10:1-20:1 mL/g): Affects mass transfer efficiency [36]

Post-Extraction Processing: Centrifugation (5000 rpm, 10min), filtration (0.22μm), and concentration (rotary evaporation at 50°C) [36].

Optimization Methodologies

Advanced statistical approaches are essential for MAE optimization:

Response Surface Methodology (RSM): Effectively models interactions between multiple parameters. For Barleria lupulina extraction, RSM with quadratic polynomial equations yielded fitted models with R² and R²adj >0.90 and non-significant lack of fit (p>0.05) [34].

Artificial Neural Networks with Genetic Algorithm (ANN-GA): Provides superior predictive accuracy for complex non-linear relationships. In stevia extraction optimization, ANN-GA achieved R² of 0.9985 with mean squared error of 0.7029, outperforming RSM models [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for MAE Implementation

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extraction Solvents | Ethanol (50-80% v/v in water) | General extraction of medium-polarity compounds | Optimal dielectric constant for microwave absorption [34] [37] |

| NADES (ChCl:Lactic acid, 2:1) | Green solvent for polar compounds | Prepared fresh by heating at 50-55°C until clear [36] | |

| Water | Extraction of highly polar compounds | Lower selectivity but environmentally benign [36] | |

| Analytical Standards | Gallic acid, Quercetin, Caffeic acid | Quantification of phenolic compounds | HPLC/UV-Vis calibration standards [34] [39] |

| Tangeretin, Nobiletin | Mandarin peel flavonoid quantification | Specific markers for citrus extracts [38] | |

| Analysis Reagents | Folin-Ciocalteu reagent | Total phenolic content assessment | Reacts with phenolic hydroxyl groups [34] [36] |

| DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) | Free radical scavenging assay | Evaluates antioxidant capacity [34] [36] | |

| ABTS (2,20-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothizoline-6-sulfonic acid)) | Additional antioxidant assessment | Reacts with both hydrophilic/lipophilic antioxidants [34] [38] | |

| Equipment | Closed-vessel microwave system | Controlled MAE under pressure | Prevents solvent evaporation, enables higher temperatures [38] |

| Centrifuge | Post-extraction separation | 5000 rpm for 10 minutes typically sufficient [36] | |

| Rotary evaporator | Extract concentration | Operated at 50°C to prevent compound degradation [36] |

Microwave-Assisted Extraction represents a technologically advanced, efficient, and sustainable approach for recovering bioactive compounds from plant materials. Its fundamental principles of volumetric heating and cell disruption mechanism enable superior performance compared to conventional extraction methods, with documented advantages in extraction efficiency, time reduction, solvent consumption, and energy utilization.

The integration of MAE with green solvents like ethanol-water mixtures and NADES, combined with advanced optimization tools such as RSM and ANN-GA, further enhances its applicability across pharmaceutical, food, and cosmetic industries. As research continues to address scale-up challenges and refine synergistic approaches with other technologies, MAE is positioned to remain a cornerstone of sustainable extraction practices in both research and industrial settings.

For researchers implementing MAE, we recommend systematic optimization of critical parameters (power, time, temperature, solvent composition) using statistical design of experiments, validation with target-specific analytical methods, and consideration of hybrid approaches where MAE is combined with complementary technologies for challenging matrices or sensitive compounds.

The growing demand for bioactive compounds from plants for use in the pharmaceutical, nutraceutical, and food industries has driven the advancement of extraction technologies. Traditional methods like Soxhlet extraction and maceration often involve lengthy processing times, high solvent consumption, and elevated temperatures that can degrade heat-sensitive compounds [40] [37]. To overcome these limitations, several novel, non-thermal extraction techniques have been developed, with Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE), Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE), and their hybrid combinations emerging as prominent green alternatives [41] [42]. These innovative methods significantly enhance extraction efficiency while reducing environmental impact by minimizing organic solvent use and energy consumption [40].