Advancing Plant Metabolomics: A Comprehensive Roadmap for Enhancing Data Quality and Reproducibility

This article provides a systematic framework for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to improve the quality and reproducibility of plant metabolomics data.

Advancing Plant Metabolomics: A Comprehensive Roadmap for Enhancing Data Quality and Reproducibility

Abstract

This article provides a systematic framework for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to improve the quality and reproducibility of plant metabolomics data. It explores foundational challenges, including the vast chemical diversity of plant metabolites and the limitations of current analytical platforms. The content details methodological best practices for experimental design, sample preparation, and data acquisition, alongside advanced troubleshooting strategies for data processing and metabolite annotation. Furthermore, it covers validation techniques for ensuring analytical reliability and examines the integration of metabolomics with other omics technologies. By addressing these critical areas, this guide aims to empower scientists to generate more robust, reproducible, and biologically insightful metabolomic data, thereby accelerating discoveries in crop improvement, natural product development, and biomedical research.

Navigating the Core Challenges and Technological Landscape of Modern Plant Metabolomics

Plant metabolomics, a key discipline within systems biology, faces significant challenges that impact the quality and reproducibility of research data. These hurdles stem from the immense structural diversity of plant metabolites, their dynamic and often unstable nature, and the limitations of existing metabolic databases. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers navigate these specific issues, thereby enhancing the reliability of their experimental outcomes.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

FAQ 1: How can I improve metabolite coverage given the vast chemical diversity in plants?

The Problem: A single plant species can contain between 7,000 to 15,000 different metabolites, with estimates suggesting over a million exist across the plant kingdom [1] [2]. This diversity, encompassing compounds with vastly different chemical properties and concentrations, makes comprehensive detection and analysis exceptionally challenging.

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Employ Multiple Analytical Platforms: No single technology can capture the entire metabolome. Combine techniques to broaden coverage.

- LC-MS: Ideal for non-volatile or thermally labile compounds, including many secondary metabolites [1] [3].

- GC-MS: Best for volatile and thermally stable compounds, such as many primary metabolites (sugars, organic acids, amino acids) after derivatization [4] [3].

- NMR: Provides highly reproducible, quantitative, and structural information for a broad range of metabolites, though with lower sensitivity than MS techniques [4] [3].

- Optimize Extraction Protocols: Use biphasic solvent systems (e.g., methanol:chloroform:water) to simultaneously extract both polar and non-polar metabolites, ensuring a broader representation of the metabolome [3].

- Utilize High-Resolution Mass Spectrometers: Instruments like Q-TOF, Orbitrap, and Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance (FT-ICR-MS) provide the high mass accuracy and resolution needed to distinguish between isobaric compounds and reduce spectral complexity [1].

Experimental Protocol for Comprehensive Profiling:

- Sample Quenching: Immediately flash-freeze plant tissue in liquid nitrogen upon harvest to quench metabolic activity and preserve the native metabolome [3].

- Homogenization: Grind the frozen tissue to a fine powder under cryogenic conditions using a mortar and pestle or a bead-based homogenizer.

- Biphasic Extraction: For every 20 mg of powdered sample, add 1 mL of a chilled methanol/water (4:1, v/v) solution. Homogenize vigorously for 5 minutes, then centrifuge. For lipid analysis, a methanol/chloroform/water system can be used [5] [3].

- Multi-Platform Analysis:

FAQ 2: What are the best practices to maintain metabolite stability from sample collection to analysis?

The Problem: Many plant metabolites are unstable and can rapidly degrade or transform due to enzymatic activity, oxidation, or improper handling, leading to inaccurate profiles.

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Immediate Quenching is Critical: The delay between sample collection and freezing is a major source of variation. Flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen is the gold standard to instantaneously halt all enzymatic activity [3].

- Control the Thermal Environment: Keep samples frozen at all times. Perform homogenization on dry ice or under liquid nitrogen to prevent thawing. Store extracts at -80°C.

- Minimize Exposure to Oxygen: For oxygen-sensitive metabolites, perform extractions under an inert atmosphere (e.g., nitrogen gas) when possible.

- Use Appropriate Solvents and Additives: Acidified solvents can stabilize certain compound classes. The use of antioxidant additives may be beneficial for specific analytes, though their use should be consistent across samples to avoid introducing bias.

Experimental Protocol for Stable Sample Preservation:

- Rapid Harvest: Collect plant material and submerge it directly into liquid nitrogen within seconds. In field conditions, use portable dry ice or ethanol-dry ice baths as alternatives, acknowledging a potential compromise in fidelity [3].

- Cryogenic Grinding: Grind the frozen tissue without allowing it to thaw. Transfer the powder to pre-cooled vials and return them to -80°C storage immediately.

- Cold Solvent Extraction: Perform all extraction steps with pre-chilled solvents and keep samples on ice or in a refrigerated centrifuge.

- Quality Control (QC) Pool: Create a QC sample by combining a small aliquot from every sample in the study. This pooled QC should be analyzed repeatedly throughout the analytical sequence to monitor instrument stability and detect any systematic degradation [3].

FAQ 3: Over 85% of LC-MS peaks are unidentified. How can I work with this "dark matter" of metabolomics?

The Problem: Due to incomplete databases and a lack of pure standards, the vast majority of metabolite features detected in untargeted LC-MS remain unannotated, limiting biological interpretation [2].

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Adopt Identification-Free Analysis Methods: Several powerful approaches bypass the need for exact identification:

- Molecular Networking: Groups metabolites based on spectral similarity, allowing you to associate unknown peaks with known compounds within the same molecular family [2].

- Discriminant Analysis: Uses statistical models (e.g., PLS-DA) to pinpoint which unknown peaks are most important for differentiating sample groups (e.g., control vs. treated), highlighting them for further study [2] [5].

- Leverage In Silico Tools: Use machine learning-based software like CANOPUS (which is part of the SIRIUS package) to predict the structural class of an unknown compound directly from its MS/MS data, even without a library match [2].

- Use Consolidated and Specialized Databases: Move beyond general libraries. Use plant-specific databases like the Reference Metabolome Database for Plants (RefMetaPlant) and the Plant Metabolome Hub (PMhub), which consolidate hundreds of thousands of plant-specific MS/MS spectra [2].

- Implement Advanced Data Processing Software: Tools like MassCube, an open-source Python framework, have been benchmarked to show superior performance in peak detection, isomer separation, and accuracy compared to other common software, leading to cleaner and more reliable data for annotation efforts [6].

Experimental Protocol for Handling Unidentified Metabolites:

- Data Pre-processing: Process your raw LC-MS/MS data using a robust pipeline (e.g., with MassCube, MS-DIAL, or XCMS) for feature detection, alignment, and MS/MS spectral extraction [6].

- Molecular Networking: Upload the processed data to the Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) platform to create a visual network of spectral similarities and explore clusters of unknown compounds [2].

- Statistical Prioritization: Perform multivariate statistical analysis (e.g., PLS-DA, PCA) on the peak table. Identify features with high Variable Importance in Projection (VIP) scores that discriminate your experimental groups. These are high-priority unknowns [5].

- Class Prediction: Run the MS/MS data for these high-priority unknowns through CANOPUS to obtain a putative classification (e.g., "flavonoid," "alkaloid"), providing a starting point for biological inference [2].

Quantitative Data on Plant Metabolomics Challenges

Table 1: The Scale of Chemical Diversity and Identification Gaps in Plant Metabolomics

| Aspect | Quantitative Measure | Source/Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolites per Species | 7,000 - 15,000 | [1] |

| Estimated Total in Plant Kingdom | Over 1 million | [2] |

| Documented Metabolites (KNApSAcK DB, 2024) | 63,723 | Highlights the vast unknown chemical space [2] |

| Unidentified LC-MS Peaks ("Dark Matter") | > 85% | Major bottleneck for data interpretation [2] |

| Annotation Rate via Library Matching | 2 - 15% (MSI Level 2) | Reflects the inadequacy of current databases [2] |

Table 2: Comparison of Major Analytical Platforms in Plant Metabolomics

| Platform | Best For | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| GC-MS | Volatile, thermally stable compounds (e.g., sugars, organic acids) | High sensitivity, reproducibility, extensive libraries | Requires derivatization, not suitable for non-volatile/labile compounds [4] [3] |

| LC-MS | Non-volatile, thermally labile, high MW compounds (broad range) | Versatile, no derivatization, high-throughput, ideal for secondary metabolites | Prone to ion suppression effects [1] [4] [3] |

| NMR | Broad-range detection, structural elucidation | Non-destructive, highly reproducible, provides structural info | Lower sensitivity, higher cost, slower data acquisition [4] [3] |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Plant Metabolomics Workflows

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Best Practice |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Nitrogen | Immediate quenching of metabolic activity upon sample harvest | Gold standard for flash-freezing to preserve metabolome integrity [3] |

| Solvents (MeOH, ACN, CHCl₃) | Metabolite extraction | Use HPLC/MS grade. MeOH/Water (4:1 v/v) for broad polar metabolite extraction [5] |

| Derivatization Reagents (e.g., MSTFA) | Making metabolites volatile for GC-MS analysis | Reacts with functional groups (-OH, -COOH) for thermal stability [3] |

| Internal Standards (e.g., Sulfachloropyridazine) | Monitoring injection performance & retention time consistency | Added to all samples prior to LC-MS analysis to correct for technical variation [5] |

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., D₂O, CD₃OD) | Solvent for NMR spectroscopy | Allows for locking and referencing in NMR analysis [3] |

| UHPLC C18 Column | Chromatographic separation of metabolites | Reversed-phase column (e.g., 1.7 µm, 50 x 2.1 mm) for high-resolution separation [5] |

Workflow and Data Analysis Diagrams

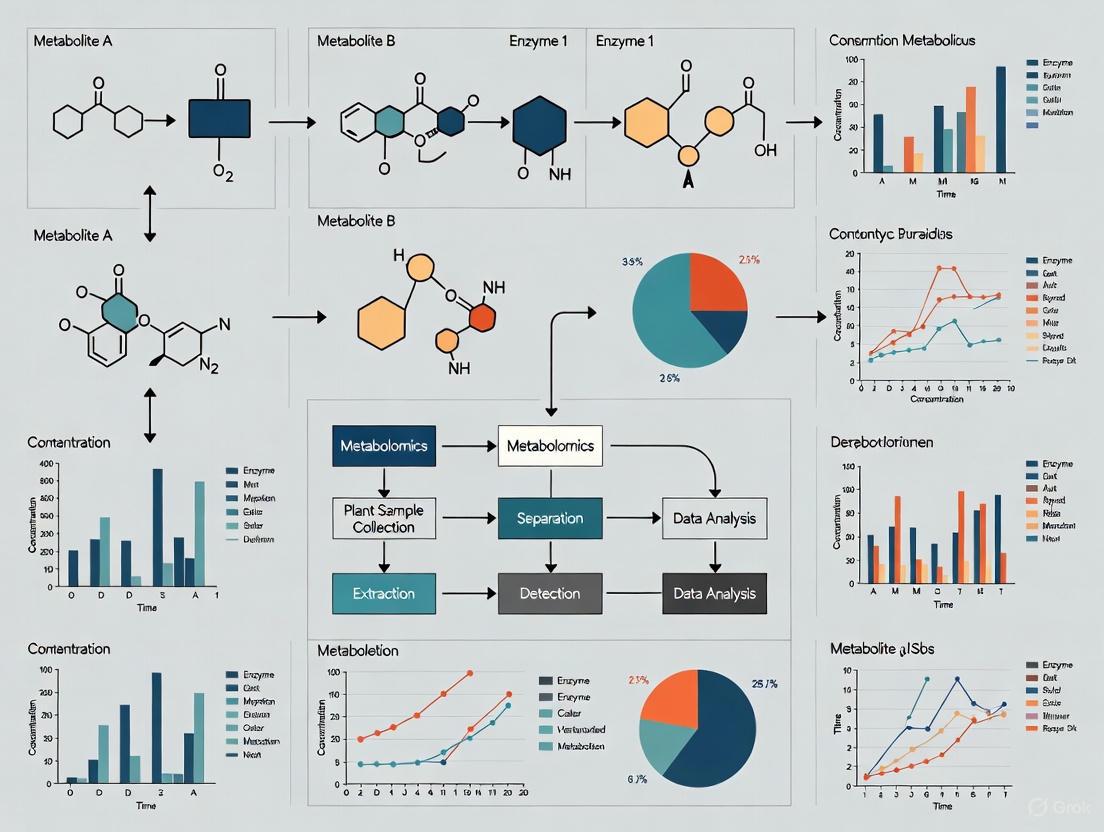

Diagram 1: Plant Metabolomics Experimental Workflow

Diagram 2: Data Analysis Pathway for Unidentified Metabolites

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why should I use multiple analytical platforms instead of just one, like LC-MS, for my plant metabolomics study? No single analytical technique can fully capture the entire plant metabolome due to the vast physicochemical diversity of metabolites [7] [8] [9]. Each platform has inherent strengths and weaknesses. Using complementary techniques like LC-MS, GC-MS, and NMR together provides broader coverage, improves the confidence of metabolite identification, and allows for cross-validation, leading to more reliable and comprehensive biological conclusions [7] [9]. For instance, one study demonstrated that combining GC-MS and NMR identified 102 metabolites, 22 of which were detected by both techniques, while 20 were unique to NMR and 82 to GC-MS [9].

Q2: What are the primary types of metabolites detected by LC-MS versus GC-MS? The separation mechanisms of these techniques make them suitable for different classes of metabolites, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Typical Metabolite Coverage of LC-MS and GC-MS

| Analytical Platform | Primary Metabolite Classes Detected | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| LC-MS | Semi-polar metabolites, most secondary metabolites [10] [7] | Flavonoids, alkaloids, phenylpropanoids [10] |

| GC-MS | Volatile metabolites, or metabolites that can be volatilized after derivatization (often primary metabolites) [10] [7] | Amino acids, sugars, organic acids [10] |

Q3: How can I assess and improve the reproducibility of my metabolomics data? Reproducibility is a major challenge in high-throughput metabolomics. Beyond traditional measures like Relative Standard Deviation (RSD), which only assesses technical variation, newer non-parametric statistical methods like the Maximum Rank Reproducibility (MaRR) procedure can be used. MaRR examines the consistency of metabolite ranks across replicate experiments to identify a cut-off point where signals transition from reproducible to irreproducible, effectively controlling the False Discovery Rate [11]. For data correction across multiple batches or studies, post-acquisition strategies like PARSEC can standardize data and reduce analytical bias without requiring long-term quality control samples, thereby improving interoperability [12].

Q4: What software tools are available for processing untargeted LC-MS data, and how do I choose? Numerous software tools exist, each with different strengths. The choice depends on your specific needs, such as data size, required accuracy, and computational expertise. Key options include:

- XCMS & MZmine: Powerful, open-source tools for peak detection, alignment, and quantification, though processing large datasets can be time-consuming [10].

- MassCube: A newer, open-source Python framework that benchmarks show has high speed, accuracy, and isomer detection capabilities compared to other algorithms [6].

- Commercial Software (e.g., Compound Discoverer): Often provide integrated workflows but may be limited to data from the vendor's own instruments [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Selecting the Right Analytical Platform

Problem: Incomplete coverage of the plant metabolome, leading to missed biological insights.

Solution: Employ an integrated platform strategy based on your research question. The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for platform selection to ensure comprehensive metabolite profiling.

Guide: Addressing Poor Reproducibility Across Batches

Problem: Biological signals are masked by high technical variability and batch effects.

Solution:

- Experimental Design: Incorporate both technical and biological replicates from the start. Use Quality Control (QC) samples, such as pooled samples from all your groups, and run them intermittently throughout your sequence to monitor instrument stability [11] [13].

- Data Processing: Apply algorithms designed to correct for batch effects. The PARSEC strategy is a post-acquisition workflow that combines batch-wise standardization and mixed modeling to reduce inter-group variability and produce a more homogeneous data distribution, thereby revealing masked biological information [12].

- Reproducibility Assessment: Use the MaRR package in R to statistically evaluate the reproducibility between your replicate experiments and identify a robust set of reproducible metabolites for downstream analysis [11].

Guide: Managing and Annotating Large-Scale Metabolomics Data

Problem: The presence of false-positive peaks, handling ultra-large datasets, and annotating unknown metabolites.

Solution:

- Reducing False Positives: Implement a multi-step filtering method during data pre-processing. Tools like ROIMCR can help by avoiding common errors introduced during peak modeling and alignment [10].

- Analyzing Large Datasets: For very large GC-MS datasets, software like QPMASS is specifically designed for efficient processing [10]. For LC-MS data, MassCube offers high-speed processing, capable of handling 105 GB of data on a laptop significantly faster than some other tools [6].

- Annotation of Unknowns: Leverage integrated omics approaches. Since a large percentage of detected metabolites are "unknown," combining metabolomics data with genetic information, such as through metabolite quantitative trait locus (mQTL) analysis, can be a powerful strategy for narrowing down candidate structures [14] [10]. Tools like MetDNA can also aid in metabolite annotation [10].

Experimental Protocols for a Multi-Platform Approach

The following workflow provides a generalized protocol for an integrated GC-MS and LC-MS untargeted plant metabolomics study, adapted from current methodologies [7].

Detailed Methodology:

Sample Preparation:

- Collection: Rapidly harvest and freeze plant tissue in liquid nitrogen to halt metabolic activity.

- Extraction: Use a comprehensive extraction solvent system (e.g., methanol:water:chloroform) to isolate a wide range of metabolites. The sample can be split for parallel LC-MS and GC-MS analysis [10] [7].

LC-MS Analysis:

- Chromatography: Utilize reversed-phase chromatography for semi-polar metabolites (e.g., flavonoids) or HILIC for more polar compounds.

- Mass Spectrometry: Acquire data in data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode, cycling between full-scan MS and MS/MS scans to collect fragmentation data for structural annotation [14].

GC-MS Analysis:

- Derivatization: Dry an aliquot of the extract and derivatize using a method like methoximation and silylation to increase the volatility and thermal stability of metabolites.

- Chromatography & MS: Use a non-polar capillary column and electron ionization (EI) for robust, reproducible fragmentation that can be matched against standard spectral libraries [7] [8].

Data Processing and Integration:

- Pre-processing: Use software like MassCube, XCMS, or MZmine to perform peak picking, alignment, and deconvolution on the LC-MS and GC-MS datasets separately [10] [6].

- Integration: Combine the processed data matrices from both platforms. Statistical tools like Multiblock PCA (MB-PCA) can be used to create a single model that identifies key variations across both datasets, providing a holistic view of the metabolic state [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Plant Metabolomics

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Methanol, Chloroform, Water | Components of standard two-phase or three-phase extraction solvents for comprehensive metabolite isolation from plant tissue [10]. |

| N-Methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (MSTFA) | Common silylation derivatization agent used in GC-MS to make metabolites volatile and thermally stable [7]. |

| Methoxyamine hydrochloride | Used in the first step of GC-MS derivatization to protect carbonyl groups (e.g., in sugars) by methoximation [7]. |

| Deuterated Solvent (e.g., D₂O, CD₃OD) | Required for NMR spectroscopy to provide a locking signal and as an internal standard for chemical shift referencing [9]. |

| Internal Standards (e.g., Stable Isotope Labeled Compounds) | Added to samples at the beginning of extraction to correct for variations in sample preparation and instrument analysis; crucial for quantification [7]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Pooled Sample | A pool made from small aliquots of all study samples; run repeatedly throughout the analytical sequence to monitor instrument performance and for data normalization [11] [13]. |

| Recombinant Inbred Lines (RILs) | A genetic population used for integrated omics analyses like linkage mapping (QTL), which helps connect metabolite accumulation patterns to genetic loci [14]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Metabolite Annotation Rates

Problem: The vast majority of metabolite signals in untargeted LC-MS analyses remain unidentified, creating a "dark matter" problem that hinders biological interpretation.

Solutions:

- Multi-dimensional Identification Strategy: Combine multiple lines of evidence for confident annotation [15]:

- MS/MS Spectral Library Matching: Compare fragmented molecular ions against reference libraries (e.g., METLIN, mzCloud, NIST, Mass Bank)

- Isotope Pattern Matching: Confirm empirical formula using isotopic distribution patterns

- Retention Time Information: Incorporate retention time data when available for higher confidence

- Collision Cross-Section (CCS) Values: Use ion mobility data where accessible

- Reference Database Comparison [15]:

| Database | Compound Coverage | Special Features | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| METLIN | Extensive | Includes various adduct forms | Limited plant-specific metabolites |

| mzCloud | ~40,000 unique compounds | MS/MS spectral trees | Only 0.1% coverage of PubChem compounds |

| NIST | GC-MS focused | Electron impact (EI) spectra | Limited for LC-MS/MS |

| Mass Bank | Public resource | Community-contributed | Inconsistent coverage |

- Five-Step Filtering Method for LC-MS: Implement systematic approach to reduce false-positive peaks and improve annotation quality [10]

Experimental Protocol for Confident Annotation:

- Sample Preparation: Use standardized extraction protocols with internal standards [16]

- Data Acquisition: Employ LC-QToF-MS with both positive and negative ionization modes [1]

- Data Processing: Utilize tools like XCMS, MZmine, or OpenMS for peak detection and alignment [10]

- Database Searching: Query multiple databases with mass error tolerance < 5 ppm [15]

- Validation: Verify annotations with standard compounds when possible [17]

Large-Scale Study Batch Effects

Problem: Instrumental drift and batch-to-batch variation in large-scale studies introduce systematic errors that compromise data quality and reproducibility.

Solutions:

- Quality Control (QC) Sample Strategy [16]:

- Prepare QC samples by pooling small aliquots of all biological samples

- Inject QC samples regularly throughout the analytical sequence (every 5-10 samples)

- Use QCs for system conditioning, monitoring instrumental performance, and data normalization

- Advanced Normalization Methods [16]:

| Normalization Method | Principle | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Total Useful Signal (TUS) | Normalizes to total signal intensity | Large-scale fingerprinting studies |

| QC-SVRC | Uses QC samples to correct drift | Multi-batch experiments |

| IS Normalization | Uses internal standard intensity | Targeted analysis with labeled IS |

| QC-norm | Robust QC-based correction | Studies with heterogeneous samples |

- Internal Standards Selection: Use deuterated analogs covering different chemical classes (e.g., lysophosphocholine, sphingolipids, fatty acids, carnitines, amino acids) to monitor retention time span and ionization efficiency [16]

Experimental Protocol for Multi-Batch Studies:

- Experimental Design: Randomize samples across batches while maintaining balanced group representation [16]

- Sample Preparation: Process in small sets (e.g., n=32 per day) to maintain consistency [16]

- Instrumental Analysis:

- Data Processing: Apply batch correction algorithms (e.g., Combat, EigenMS) to remove inter-batch variation [18]

Data Processing and Visualization Challenges

Problem: Complex metabolomics datasets require specialized statistical approaches and visualization strategies for proper interpretation.

Solutions:

- Missing Value Management [18]:

- Classification: Identify whether missing values are MCAR, MAR, or MNAR

- Imputation Strategies:

- k-nearest neighbors (kNN) for MCAR/MAR

- Half-minimum (hm) imputation or quantile regression for MNAR

- Random forest for complex missing patterns

Statistical Analysis Workflow:

Figure 1: Data Visualization Selection Guide

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Fundamental Concepts

What exactly is the "dark matter" problem in plant metabolomics? The term refers to the significant portion of metabolite signals detected in untargeted LC-MS analyses that remain chemically unidentified. Current MS/MS libraries cover only about 0.1% of known small molecules, leaving most detected compounds unannotated and creating a major bottleneck in biological interpretation [17].

Why is metabolite identification so challenging compared to other omics fields? Unlike genomics where sequences map to known databases, metabolomics faces several unique challenges [17]:

- Structural Diversity: Plants contain over 200,000 metabolites with enormous chemical diversity [1]

- Dynamic Range: Metabolite concentrations can vary by orders of magnitude [18]

- Instrumental Limitations: No single analytical platform can detect all metabolites [10]

- Database Gaps: Limited reference spectra for plant-specialized metabolites [17]

How can we assess confidence in metabolite identifications? Confidence levels follow a standardized framework [15]:

- Level 1: Identified by reference standard (highest confidence)

- Level 2: Putatively annotated based on spectral similarity

- Level 3: Putatively characterized compound class

- Level 4: Unknown compounds (lowest confidence)

Technical Challenges

What are the best practices for handling missing values in metabolomics data? Approach depends on the nature of missingness [18]:

- MNAR (Missing Not at Random): Use half-minimum imputation or quantile regression

- MCAR/MAR (Missing Completely/At Random): Apply k-nearest neighbors or random forest imputation

- Filtering: Remove metabolites with >35% missing values before imputation

How do we choose between different mass spectrometry platforms? Selection depends on research goals and metabolite classes of interest [1]:

| Platform | Optimal Application | Key Metabolite Classes | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| GC-MS | Primary metabolites, volatiles | Amino acids, sugars, organic acids | Requires derivatization |

| LC-MS (RP) | Secondary metabolites | Flavonoids, alkaloids, lipids | Limited for very polar compounds |

| LC-MS (HILIC) | Polar metabolites | Sugars, amino acids | Longer equilibration times |

| CE-MS | Ionic species | Organic acids, nucleotides | Lower robustness |

What normalization strategies are most effective for large-scale studies? For plant metabolomics involving hundreds of samples [16]:

- QC-based Normalization: Most robust for multi-batch studies

- Total Useful Signal (TUS): Effective for fingerprinting approaches

- Internal Standard-Based: Limited to targeted analyses with comprehensive IS coverage

- Probabilistic Quotient Normalization: Handles dilution effects well

Data Analysis & Interpretation

What visualization strategies are most effective for communicating metabolomics results? Effective visualization depends on the analysis stage and audience [21] [19]:

- Exploratory Analysis: PCA scores plots, hierarchical clustering heatmaps

- Differential Analysis: Volcano plots, annotated box plots

- Time Series: Line plots, clustered heatmaps

- Pathway Analysis: Enrichment plots, metabolic network diagrams

How can we integrate metabolomics with other omics data? Successful multi-omics integration requires [22] [20]:

- Experimental Design: Coordinated sample collection for all omics layers

- Data Transformation: Appropriate scaling and normalization across data types

- Multivariate Statistics: PLS-based methods for correlation analysis

- Pathway Mapping: Joint visualization on metabolic networks

- Database Integration: Leveraging resources like Plant Metabolic Network (PMN)

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Materials for Plant Metabolomics

| Reagent/ Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Internal Standards | Monitor extraction efficiency, ion suppression | Use chemical analogs covering different classes [16] |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | Mobile phase preparation | Minimize background contamination [16] |

| Quality Control Pool | Monitor instrumental performance | Prepare from sample aliquots or representative pool [16] |

| Derivatization Reagents | Enable GC-MS analysis of non-volatiles | MSTFA for trimethylsilylation, methoxyamination [10] |

| Solid Phase Extraction Cartridges | Fractionate complex extracts | C18 for non-polar, HILIC for polar metabolites [10] |

| Stable Isotope Labels | Track metabolic fluxes | 13C, 15N, 2H for dynamic studies [17] |

Instrumentation and Software Tools

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|

| Data Processing | XCMS, MZmine, OpenMS | Peak detection, alignment, quantification [10] |

| Statistical Analysis | MetaboAnalyst, metaX | Statistical analysis, biomarker discovery [10] [18] |

| Database Search | METLIN, mzCloud, Mass Bank | Metabolite identification [15] |

| Pathway Analysis | PlantCyc, KEGG, PMN | Metabolic pathway mapping [20] |

| Visualization | Cytoscape, ggplot2, Plotly | Network graphs, publication figures [21] [18] |

Experimental Workflow for Enhanced Metabolite Identification

Figure 2: Enhanced Metabolite Identification Workflow

Advanced Strategies for Overcoming the Bottleneck

Emerging Technologies and Approaches

Spatial Metabolomics: Mass spectrometry imaging techniques enable precise localization of metabolite distribution in plant tissues, providing crucial contextual information for biological interpretation [1].

Single-Cell Metabolomics: Emerging technologies allow metabolite detection at cellular resolution, revealing heterogeneity masked in bulk tissue analyses [1].

Integrated Multi-Omics Frameworks: Combining metabolomics with genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics provides complementary data layers for comprehensive biological understanding [22] [20].

Machine Learning Applications: Advanced computational approaches including deep learning show promise for predicting metabolite structures from MS/MS spectra and improving annotation rates [21].

Public Database Development: Efforts to expand plant metabolite databases (Plant Metabolic Network, Metabolomics Workbench) are crucial for improving annotation coverage [20].

Standardization Initiatives: Guidelines from the Metabolomics Society and International Lipidomics Society promote data quality and reproducibility through standardized reporting [18].

Open-Source Tool Development: Community-driven software development (R, Python packages) provides accessible analytical tools for the research community [18].

Plant metabolomics has traditionally relied on the analysis of homogenized bulk tissues. However, this approach averages metabolite signatures across diverse cell types, diluting critical spatial information that is fundamental to understanding plant physiology, stress responses, and specialized metabolism. Spatial metabolomics, particularly through Mass Spectrometry Imaging (MSI), has emerged to address this gap by enabling the in-situ visualization of metabolite distribution within plant tissues [23] [24]. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and detailed protocols to help researchers integrate these advanced spatial techniques, thereby enhancing the quality and reproducibility of plant metabolomics data.

Key Questions & Answers: A Technical Support Guide

Q1: What are the fundamental limitations of bulk tissue metabolomics that spatial methods overcome?

Bulk tissue analysis, while valuable, presents several critical limitations for modern plant research:

- Dilution of Metabolic Phenotype: Homogenizing various cell types together makes it impossible to map metabolites back to their specific locations within organelles, cells, or tissues. This dilutes metabolites that may have crucial roles in specific cell-type responses, making them challenging to detect and investigate [23].

- Loss of Spatial Regulation Context: Plant metabolism is highly organized and regulated within subcellular organelles, specific tissues, and even individual cells. Bulk analysis loses this spatial context, which is vital for understanding the function and regulation of biochemical pathways [23] [25].

- Masking of Cellular Heterogeneity: Averaging metabolite levels across a tissue obscures important biological heterogeneity between cell types, which can play significant roles in physiological processes like stomatal regulation, C4 metabolism, and the function of shoot apical meristems [25].

Q2: Which spatial metabolomics technologies are most applicable to plant research, and how do I choose?

The most common MSI technologies for plant metabolomics are Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI) and Desorption Electrospray Ionization (DESI). The choice depends on your research goals, considering spatial resolution, detectable mass range, and sample preparation requirements. The table below compares the core technologies.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Mass Spectrometry Imaging (MSI) Technologies for Plant Metabolomics

| Technology | Ionization Type | Spatial Resolution | Mass Range | Key Advantages | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MALDI-MSI [23] [24] | Soft | 5 - 100 µm | 300 - 100,000 Da | High spatial resolution; suitable for a wide range of metabolites, including large molecules. | Requires a matrix, making sample preparation time-consuming; matrix interference signals possible. |

| DESI-MSI [23] [24] | Soft | 40 - 200 µm | 100 - 2,000 Da | Ambient conditions (no vacuum); requires no matrix, simplifying preparation. | Lower spatial resolution compared to MALDI. |

| SIMS-MSI [24] | Hard | 0.1 - 1 µm | < 2,000 Da | Highest spatial resolution for subcellular analysis. | Hard ionization causes extensive fragmentation; limited to smaller molecules. |

The following decision pathway can guide you in selecting the appropriate technology:

Q3: What is a detailed protocol for a standard MALDI-MSI experiment in plant tissue?

A robust MALDI-MSI workflow involves several critical steps to ensure high-quality, reproducible data.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for a Plant MALDI-MSI Experiment

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT) Compound | Embedding medium for cryo-sectioning | Must be carefully washed off to avoid interference with MS analysis [25]. |

| Matrix Compound | Absorbs laser energy and facilitatesdesorption/ionization of metabolites | Choice is metabolite-dependent (e.g., DHB for flavonoids, CHCA for lipids) [25]. |

| Cryostat | Instrument for thin-sectioning frozen samples | Typically sections at 5-20 µm thickness [24]. |

| Standard Metabolites | For instrument calibration and validation | Use compounds expected in your sample for relevant mass range. |

| Conductive Glass Slides | Sample substrate for MALDI-MS | Required for the ionization process in the mass spectrometer. |

Experimental Protocol:

Sample Preparation & Sectioning:

- Rapidly freeze fresh plant tissue (e.g., leaf, root, nodule) in liquid nitrogen to preserve metabolic state and spatial integrity.

- Embed the frozen tissue in OCT compound and section into thin slices (typically 5-20 µm) using a cryostat [24].

- Thaw-mount the sections onto pre-chilled conductive glass slides. Carefully wash slides to remove OCT compound, which can suppress ionization [25].

Matrix Application:

- Apply a matrix solution (e.g., 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB) for general metabolites) uniformly onto the tissue section. This is critical for the desorption/ionization process.

- Use a sprayer or solvent-free sublimation method. Sublimation reduces metabolite delocalization but may not ionize all metabolites equally [25].

Data Acquisition (MALDI-MSI):

- Load the slide into the MALDI mass spectrometer.

- The instrument rasterizes the laser across the tissue section in a predefined grid. The pixel size determines the spatial resolution (e.g., 5 µm to 100 µm) [23].

- A full mass spectrum is acquired at each pixel, creating a hyperspectral dataset that links molecular information (mass-to-charge ratio, m/z) with spatial coordinates (x, y).

Data Processing & Visualization:

- Use specialized MSI software (e.g., SCiLS Lab, MSiReader, open-source tools) to process the data.

- Steps include peak picking, alignment, and normalization.

- Generate ion images for specific m/z values to visualize the spatial distribution of individual metabolites across the tissue [24].

Q4: How can I assess and improve the reproducibility of my spatial metabolomics data?

Reproducibility is a major challenge in metabolomics. Here are key strategies:

- Adopt Standardized Reporting: Follow reporting guidelines from consortia like the Metabolomics Association of North America (MANA). Detail every aspect of your experiment: study design, sample preparation, data acquisition parameters, and processing methods [26] [27].

- Incorporate Quality Control (QC):

- Use pooled quality control samples from your experimental cohort. Analyze these QC samples throughout your acquisition sequence to monitor instrument stability.

- For NMR, use a standardized buffer and a calibrated internal standard for chemical shift reference [26].

- Employ Robust Statistical Methods:

- Use the Maximum Rank Reproducibility (MaRR) procedure, a non-parametric method, to assess reproducibility between replicate experiments (technical or biological). It identifies the point where highly correlated, reproducible signals transition to irreproducible ones without relying on arbitrary cut-offs [28].

- Perform multivariate statistical analysis like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) to identify major sources of variation and validate group separations [29].

Q5: Can you provide a real-world example where spatial metabolomics revealed what bulk analysis missed?

A compelling application is the study of soybean nodules under drought and alkaline stress. While bulk metabolomics could identify overall changes in flavonoid content, spatial metabolomics using MSI revealed precisely how the distribution of specific isoflavones within the nodule tissue was altered by these stresses [30]. This spatial redistribution is likely a key part of the plant's stress adaptation strategy, information that would be entirely lost in a homogenized bulk analysis.

Visualization of Core Concepts

The Workflow and Information Gap in Bulk vs. Spatial Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental difference in workflow and data output between traditional bulk metabolomics and spatial metabolomics, highlighting the critical loss of information in the bulk approach.

The adoption of spatial metabolomics techniques marks a significant leap forward in plant science. By moving beyond bulk tissue analysis, researchers can now investigate the intricate spatial localization of metabolites, which is fundamental to understanding plant development, stress responses, and the synthesis of valuable specialized compounds. By utilizing the troubleshooting guides, detailed protocols, and reproducibility checks provided in this technical support center, researchers can systematically overcome common challenges and generate high-quality, spatially resolved metabolomics data. This advancement is pivotal for improving data quality and reproducibility, ultimately driving more insightful and impactful plant research.

Implementing Robust Workflows: From Experimental Design to Data Acquisition

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My plant metabolomics study failed to find statistically significant biomarkers. Could my experimental design be at fault?

A common reason for this issue is inadequate statistical power. In the context of high-dimensional metabolomics data, where you measure thousands of metabolites, a small sample size drastically reduces your probability of detecting real biological effects. Power is the probability that your test will correctly reject a false null hypothesis (i.e., find a real effect) [31] [32]. A study with low power is likely to produce false-negative results, leading to missed discoveries.

Before collecting data, conduct an a priori power analysis to determine the sample size needed. You will need to define your desired power (typically 0.80 or 80%), significance level (alpha, typically 0.05), and the expected effect size [33] [32]. For plant metabolomics, where biological variability can be high, careful consideration of sample size is crucial [26].

Q2: What is the difference between technical and biological replication in plant metabolomics, and why does it matter?

This distinction is fundamental for reproducible research.

- Biological Replicates are measurements taken from different, independent biological sources (e.g., different plants, different plots, or different leaves from different plants). They account for the natural biological variation within a population and allow you to generalize your findings. True replication in an experiment refers to the inclusion of multiple biological replicates per condition [26].

- Technical Replicates are repeated measurements of the same biological sample (e.g., injecting the same extract multiple times into the mass spectrometer). They help assess the variance introduced by your analytical equipment and protocols but do not provide information about biological variability [26].

To draw meaningful conclusions about a plant population, your experimental design must include true biological replication. Relying solely on technical replicates inflates the perceived precision of your experiment and limits the scope of your inferences.

Q3: How can I implement proper randomization during sample preparation and analysis?

Randomization is a critical defense against confounding bias and systematic error. In plant metabolomics, you should randomize at two key stages:

- Sample Processing Order: The order in which biological samples are prepared for analysis (e.g., extraction, derivatization) should be randomized. This prevents a systematic bias where all samples from one treatment group are processed at the beginning of the day when an instrument might be stabilizing.

- Instrument Run Order: The sequence in which prepared samples are injected into your analytical platform (e.g., LC-MS, GC-MS, NMR) should also be randomized [34].

A simple method is to use a random number generator to assign each sample a position in the processing and analysis sequence. This ensures that any unmeasured technical variability (e.g., instrument drift, reagent batch effects) is distributed randomly across your experimental groups and does not become confounded with your biological signal.

Power Analysis Parameters for Metabolomic Studies

Table 1: Key parameters to determine for an a priori power analysis.

| Parameter | Description | Considerations for Plant Metabolomics |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Power (1-β) | The probability of detecting a true effect. Typically set to 0.80 or higher [31]. | High-dimensional data may require adjustments for multiple testing, which can reduce power. |

| Significance Level (α) | The probability of a Type I error (false positive). Typically set to 0.05 [32]. | In metabolomics, the alpha level may be corrected for thousands of simultaneous metabolite tests. |

| Effect Size | The magnitude of the difference or relationship you expect to detect. Often estimated from pilot data or literature [31]. | Can be challenging to estimate. Consider what minimal difference is biologically or clinically relevant [31] [32]. |

| Biological Variability | The natural variance in metabolite levels within your plant population [26]. | Well-controlled systems (e.g., cell cultures) have lower variability than field studies. More variable systems require larger sample sizes [26]. |

Experimental Protocols for Robust Metabolomics

Protocol: A Priori Power and Sample Size Determination

- Define Your Hypothesis: Clearly state the primary metabolic contrast you wish to test (e.g., "Does drought stress alter the abundance of flavonoids in Arabidopsis leaves?").

- Choose Your Analysis Method: Identify the primary statistical test you will use (e.g., t-test, ANOVA, regression). This determines the type of power analysis [33].

- Estimate Parameters: Use pilot data or published literature to estimate the expected effect size and biological variability for your key metabolites of interest. If no data exists, a minimal scientifically important difference can be used [32].

- Run the Analysis: Use statistical software (e.g., G*Power, R) to calculate the necessary sample size per group, given your chosen power (0.8), alpha (0.05), and estimated effect size [33].

- Incorporate Replication: The calculated sample size refers to the number of biological replicates per group. Plan for additional samples if you intend to include technical replicates for quality control.

Protocol: Implementing True Replication and Randomization

- Design Your Replication Structure:

- Decide on the number of biological replicates (e.g., 10 individual plants per treatment group).

- Decide if technical replicates are needed for quality control (e.g., running a pooled quality control sample repeatedly to monitor instrument stability) [35].

- Generate a Randomized Sample List:

- Assign a unique ID to every biological sample.

- Use a random number generator to create a random order for both sample preparation and instrumental analysis.

- Adhere strictly to this randomized list throughout the workflow.

- Document the Process: Record the randomized sequence used. This is essential metadata for reviewers and for your own reference during data analysis.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential materials for a plant metabolomics workflow.

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Pooled Quality Control (QC) Sample | A pool of all experimental samples; injected repeatedly throughout the analytical run to monitor and correct for instrumental drift [35]. |

| Internal Standards (Isotopically Labeled) | Compounds added to each sample at a known concentration before extraction; used to correct for variability in sample preparation and instrument response [35]. |

| Standardized Reference Materials | Certified reference materials used to validate the accuracy and reproducibility of the analytical method across different laboratories [35]. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Diagram 1: Foundational experimental design workflow.

Diagram 2: Factors that increase statistical power.

The reproducibility and quality of plant metabolomics data are fundamentally dependent on the initial steps of sample preparation. Inconsistent practices in harvesting, drying, and extraction can introduce significant variability, obscuring true biological signals and compromising downstream analyses. This guide addresses critical challenges and provides standardized, actionable protocols to enhance the reliability of your plant metabolomics research.

Experimental Design and Power Analysis

Formulating a Research Hypothesis and Power Analysis

A clearly defined research hypothesis (RH) is the cornerstone of a well-designed experiment. It should be directly linked to the metabolic pathways and metabolites of interest, guiding the selection of appropriate analytical tools [36].

- Biological and Experimental Units: Clearly define biological units (BUs), experimental units (EUs), and observational units (OUs) to avoid pseudo-replication. Sampling different parts of the same plant does not constitute true replication; independent plants should be used to capture genuine biological variation [36].

- Randomization: Randomize the order of sample collection and treatment application to distribute systematic effects evenly and minimize bias [36].

- Sample Size and Power Analysis: The high dimensionality of metabolomics data makes determining the right sample size challenging. Conduct a statistical power analysis a priori to identify the minimum sample size required to achieve the desired effect and level of significance, thereby reducing false positives (type I errors) and false negatives (type II errors) [36]. Tools like MetSizeR and MetaboAnalyst offer practical methods for sample size calculation in high-dimensional data [36].

Table: Tools for Power Analysis in Omics Studies

| Omics Field | Specific Challenges | Recommended Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolomics | High dimensionality, multicollinearity between variables, sample heterogeneity [36]. | MetSizeR, MetaboAnalyst [36] |

| Lipidomics | Variety in lipid polarity, size, and solubility; technical variability [36]. | LipidQC, MS-DIAL [36] |

| Fluxomics | Integrating metabolic and isotopic data; variations in isotope incorporation [36]. | 13CFlux, INCA [36] |

| Peptidomics | Peptide degradation; instrument sensitivity; data complexity [36]. | Skyline, MaxQuant [36] |

| Ionomics | High-dimensional ion concentration data; influence of genotype and environment [36]. | ionomicQC, MetaboAnalyst [36] |

Design of Experiments (DOE)

A structured DOE is essential for minimizing errors and ensuring reproducibility. It systematically identifies key variables and optimizes responses relevant to the research hypothesis [36].

- Screening Designs: Use Fractional Factorial Designs (FDs) or Plackett-Burman Designs (PBDs) to identify significant variables with a minimal number of experiments.

- Optimization Designs: Employ response surface methodologies like Box-Behnken (BB) or Central Composite Design (CCD) to determine optimal conditions for sample preparation [36].

Experimental Design Optimization Workflow

Sample Collection and Harvesting

How should plant samples be collected and handled post-harvest?

Proper collection and immediate post-harvest handling are critical for preserving the in-vivo metabolic state.

- Sampling Strategy: Employ stratified or random sampling to ensure unbiased representation of the population. Consider plant type, growth stage, and environmental conditions (soil, moisture, temperature) as these factors significantly influence metabolite profiles [37].

- Timing: Sample during periods of stable metabolite concentration, often in the early morning. Avoid sampling during environmental stress (drought, extreme temperatures) [37].

- Tools and Containers: Use sterilized scissors, scalpels, or pruners. Collect samples into pre-labeled cryovials, glass vials, or sterile bags. Wear gloves to prevent contamination [37].

- Rapid Stabilization: The highest priority is to quench metabolic activity immediately after harvest. Flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen is the gold standard. For tissues intended for Non-Structural Carbohydrate (NSC) analysis, freezing has been shown to significantly reduce sugar and NSC losses compared to microwaving or direct oven-drying [38].

Table: Comparison of Sample Preservation Methods for Metabolite Analysis

| Method | Protocol | Best For | Advantages | Disadvantages/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flash-Freezing | Immediate immersion in liquid nitrogen; store at -80°C [37]. | Most metabolites, especially labile compounds; Non-Structural Carbohydrates (NSCs) [38]. | Excellent preservation of metabolic state; simple. | Requires access to liquid nitrogen and ultra-low freezers. |

| Microwave Drying | 3 cycles of 30s at 700W for small samples, followed by oven drying [38]. | Fieldwork with no immediate freezer access. | Rapid enzyme denaturation; portable equipment. | Risk of uneven heating; less effective for NSC preservation in some tissues [38]. |

| Freeze-Drying (Lyophilization) | Flash-freeze, then sublimate water under vacuum; store desiccated [37]. | Long-term storage; volatile compounds; structural integrity. | Preserves structure and heat-sensitive compounds. | Time-consuming and expensive equipment. |

| Oven Drying | Drying at 40-70°C for 48-72 hours [39] [37]. | Robust, non-labile metabolites (e.g., some flavonoids). | Low cost and high throughput. | Can degrade heat-labile and volatile compounds; not recommended for primary metabolism [39]. |

Drying and Homogenization

What are the best practices for drying and grinding plant material?

The goal of drying is to halt enzymatic and microbial activity without degrading metabolites. Homogenization creates a uniform powder for reproducible extraction [37].

- Drying Methods:

- Freeze-Drying (Lyophilization): The preferred method for most metabolomic studies as it best preserves the original metabolic profile by removing water via sublimation from a frozen state, minimizing thermal degradation [37].

- Oven Drying: Use controlled low temperatures (40-60°C). While faster and cheaper, this method risks the loss of volatile compounds and degradation of heat-labile metabolites [39] [37].

- Air Drying: A gentle but slow process that should be conducted away from direct sunlight to prevent photo-degradation [37].

- Homogenization Methods:

- Cryogenic Grinding: Cooling samples with liquid nitrogen before grinding in a mortar and pestle or ball mill. This is the best method as it makes brittle tissues easier to pulverize and prevents heat buildup, preserving volatile and labile compounds [37].

- Ball Mill Grinding: Effective for achieving a uniform, fine powder from larger quantities of material [37].

Sample Processing Workflow from Drying to Homogenization

Metabolite Extraction

How do I choose the right extraction method?

No single analytical technique can capture the full range of plant metabolites, from highly polar to non-polar [36]. The choice of extraction protocol is therefore dictated by the target metabolome.

- Solvent Extraction: The most common technique. The choice of solvent (e.g., methanol, ethanol, chloroform, water) determines the polarity range of extracted metabolites. Mixtures like methanol:water:chloroform are used for comprehensive extraction of both polar and non-polar compounds [40] [37].

- Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE): Used to clean up samples or fractionate extracts by passing them through a solid adsorbent, which selectively retains certain compound classes. This reduces matrix effects in subsequent LC-MS analysis [37] [41].

- Liquid-Liquid Partitioning: Separates metabolites based on their differential solubility in two immiscible solvents, useful for fractionating complex extracts [37].

- Ultrasonic Extraction: Uses ultrasound to agitate the solvent, enhancing mass transfer and improving extraction yield while reducing time [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Reagents for Plant Sample Preparation and Nucleic Acid Extraction

| Reagent/Category | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Nitrogen | Rapid freezing for metabolic quenching and cryogenic grinding [37]. | Preserving labile metabolites; homogenizing fibrous tissues. |

| Methanol, Ethanol, Chloroform | Solvents for metabolite extraction [40] [37]. | Extracting a broad range of polar and non-polar metabolites. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Columns | Sample clean-up and fractionation [37] [41]. | Removing salts and pigments before LC-MS analysis. |

| CTAB (Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) | Cationic detergent for breaking down cell membranes [42]. | Genomic DNA extraction, especially from polysaccharide-rich plants. |

| PVP (Polyvinylpyrrolidone) | Binds and removes phenolic compounds [42]. | Preventing polyphenol oxidation and co-precipitation with DNA. |

| EDTA (Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) | Chelating agent that binds Mg²⁺ and Ca²⁺ ions [42]. | Inactivating DNases and metalloproteases to protect nucleic acids and proteins. |

| β-Mercaptoethanol | Potent reducing agent [42]. | Cleaning tannins and polyphenols; preventing disulfide bond formation in proteins. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

We see high variability in our LC-MS results. What could be going wrong during sample prep?

High variability often stems from inconsistencies in the early stages of sample processing. Key things to check:

- Inadequate Sample Cleanup: Complex plant matrices can cause ion suppression or enhancement in the MS. Implement appropriate cleanup techniques like SPE [41].

- Improper Sample Storage: Store samples at -80°C and avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles. Use amber vials for light-sensitive compounds [41].

- Matrix Effects: Use matrix-matched calibration standards and stable isotope-labeled internal standards to correct for these effects [43] [41].

- Carry-Over Effects: Run blank injections between samples and use appropriate needle wash solvents to prevent false positives [41].

What is the biggest mistake to avoid when preparing plant samples for metabolomics?

The most critical mistake is failing to quench metabolism quickly and consistently after harvest. Metabolic turnover continues rapidly after sampling, altering the profile you intend to measure. The time between harvesting and stabilization (e.g., freezing in liquid nitrogen) must be minimized and kept identical for all samples in a study to ensure data integrity [37] [38].

Over 85% of LC-MS peaks remain unidentified in plant studies. How can we still get biological insights?

This "dark matter" of metabolomics is a known challenge [2]. Identification-free analysis strategies can provide powerful biological insights:

- Molecular Networking: Groups MS/MS spectra based on similarity, revealing families of related compounds without needing identities [2].

- Distance-Based Approaches: Uses multivariate statistics to compare global metabolic patterns between sample groups [2].

- Information Theory-Based Metrics: Quantifies the complexity and diversity of metabolic profiles [2].

- Discriminant Analysis: Pinpoints metabolite signals (even unknown ones) that are most influential in discriminating between experimental conditions [2].

Why is our DNA yield low or quality poor for PCR?

Plant tissues are challenging due to contaminants that co-precipitate with DNA.

- Polysaccharides: Form viscous solutions and inhibit enzymes. CTAB-based methods are designed to remove them [42].

- Polyphenols: Oxidize and irreversibly bind to DNA, causing browning and inhibition. Use PVP or β-Mercaptoethanol in your extraction buffer to combat this [42].

- Tissue Choice: Younger leaves generally contain fewer secondary metabolites and are preferable to older tissues [42].

- DNases: Ensure all equipment is clean and use EDTA in your extraction buffer to chelate Mg²⁺, a necessary cofactor for DNases [42].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary MSI techniques for spatial metabolomics in plant research, and how do I choose? The three primary MSI techniques are MALDI-MSI, DESI-MSI, and SIMS-MSI. Your choice depends on your research goals, considering factors like spatial resolution, sample preparation needs, and the types of metabolites you are targeting [24] [44].

The table below compares these core techniques:

| Parameter | MALDI-MSI | DESI-MSI | SIMS-MSI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionization Type | Soft | Soft | Hard [24] |

| Spatial Resolution | 5 - 100 μm [24] | 40 - 200 μm [24] | 0.1 - 1 μm [24] |

| Matrix Required? | Yes [24] | No [24] [44] | No [24] |

| Mass Range | 300 - 100,000 Da [24] | 100 - 2,000 Da [24] [45] | < 2,000 Da [24] |

| Key Advantage | High spatial & mass resolution [45] [44] | Minimal sample prep, ambient conditions [45] [44] | Highest spatial resolution, suitable for single-cell imaging [44] |

| Key Limitation | Requires matrix application; matrix ions can interfere with small molecules [45] [44] | Lower spatial resolution and sensitivity compared to MALDI [45] [44] | High energy ionization can fragment molecules; lower ionization efficiency for intact molecules [44] |

Q2: How can I overcome the challenge of the plant cuticle for metabolite detection? The waxy plant cuticle significantly limits metabolite detection. A powerful solution is the Plant Tissue Microarray (PTMA) method combined with MALDI-MSI (MALDI-MSI-PTMA) [46]. This technique involves homogenizing plant tissues, embedding them in a gelatin mould, and cryo-sectioning to create arrays, thereby breaking down the physical barriers of the cuticle, wax, and cell walls [46]. This method allows for high-throughput metabolite detection and imaging of over 1000 samples per day with high reproducibility and stability [46].

Q3: What are common causes of poor reproducibility in spatial metabolomics data? Reproducibility is affected by numerous technical and biological variables. Key factors include:

- Sample Preparation: Inconsistent processing days and storage times of samples significantly impact the metabolome [47]. For cell cultures, even factors like incubator humidity gradients can introduce artifacts [48].

- Instrumental Factors: Batch effects during data acquisition are a major source of variation that must be corrected with quality control (QC) measures [47].

- Data Acquisition Mode: In untargeted LC-MS, Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) has demonstrated superior reproducibility with a lower coefficient of variance (10%) compared to Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA, 17%) [49].

- Biological Variation: Biological replicates naturally show more variation than technical replicates, which must be accounted for in experimental design [11].

Q4: How can I improve the reproducibility of my plant-metabolome experiments? Adopting standardized, detailed protocols is the most effective way to enhance reproducibility. A recent multi-laboratory study successfully demonstrated high reproducibility in plant-microbiome research by distributing all key materials (EcoFAB devices, seeds, inoculum) from a central lab and providing detailed, video-annotated protocols for every step [50]. Furthermore, using statistical methods like the non-parametric Maximum Rank Reproducibility (MaRR) procedure can help assess and filter for reproducible metabolite signals across replicate experiments [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Metabolite Signal from Intact Plant Tissue Sections

Problem: Despite seemingly good tissue preparation, the number of metabolite ions detected from the surface of an intact plant tissue section is low, likely due to the multi-layer structure of plant tissues (e.g., epicuticular wax, cuticle, cell wall) preventing metabolite release [46].

Solution: Implement the Plant Tissue Microarray (PTMA) protocol.

| Step | Procedure | Key Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Homogenization | Homogenize the plant tissue (e.g., leaves, stems, roots) to break down cellular structures. | This step physically disrupts the cuticle and cell walls, making metabolites accessible [46]. |

| 2. Embedding | Fill the homogenized tissue into a gelatin mould to create the PTMA block. | The mould standardizes the sample format for high-throughput analysis [46]. |

| 3. Sectioning | Cryo-section the PTMA block into thin sections using a cryostat (e.g., Leica CM1860). | Sections are typically 5-20 μm thick. The thin sections are thaw-mounted onto ITO-coated glass slides [46]. |

| 4. Matrix Application | Apply a suitable matrix (e.g., 2-MBT) uniformly onto the PTMA sections. | Automated spraying or sublimation ensures uniform coating, which is critical for ionization efficiency and reproducible imaging [46] [44]. |

This workflow overcomes the limitations of direct on-tissue analysis, enhancing the detection of endogenous metabolites [46].

Issue 2: Inconsistent or Irreproducible Results Between Replicates

Problem: Metabolite abundance or spatial distribution patterns are not consistent across technical or biological replicates, making biological interpretation difficult.

Solution: A multi-faceted approach targeting major sources of variability.

| Source of Variability | Troubleshooting Action | Protocol/Standard |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Processing | Control and document processing day and storage time meticulously. Process all samples for a given experiment in the same batch if possible. | Store cellular extracts at -80 °C and minimize storage time variance. Studies show processing day has a significant impact [47]. |

| Instrument Performance | Implement a System Suitability Test (SST) prior to analysis and use Quality Control (QC) samples (e.g., pooled QC) throughout the run to monitor performance and correct for batch effects. | Use a standard mix (e.g., eicosanoids) to evaluate detection power and reproducibility of the instrumental setup [49]. |

| Data Analysis | Use robust statistical methods to formally assess reproducibility and filter out irreproducible signals. | Apply the MaRR (Maximum Rank Reproducibility) procedure to identify metabolites that show consistency across replicate experiments, controlling the False Discovery Rate [11]. |

| Experimental Design | Avoid the One-Variable-At-Time (OVAT) approach. Use Design of Experiments (DoE) to systematically test factors and their interactions. | Techniques like Fractional Factorial Designs or D-optimal designs can efficiently optimize multiple sample preparation parameters simultaneously [13]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item Name | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| ITO-coated Glass Slides | Provides a conductive surface required for MALDI-MSI analysis to facilitate ionization and prevent charging [46]. |

| MALDI Matrices (e.g., DHB, CHCA, 2-MBT) | Low molecular-weight compounds that absorb laser energy, facilitating the desorption and ionization of metabolites from the tissue surface [44]. The choice of matrix is critical for ionization efficiency. |

| Cryostat (e.g., Leica CM1860) | A precision instrument used to cut thin (e.g., 5-20 μm) sections of frozen tissue or PTMA blocks for imaging [46] [44]. |

| Gelatin Mould (for PTMA) | Used to embed homogenized plant tissues into a standardized block format, enabling high-throughput, reproducible sectioning [46]. |

| System Suitability Test (SST) Standards | A mix of known standard compounds (e.g., eicosanoids) run at the start of a sequence to verify instrument performance is adequate for the intended analysis [49]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Sample | A pooled sample representing all analytes in the study, injected repeatedly throughout the analytical batch to monitor instrument stability and for data correction [47] [49]. |

| EcoFAB 2.0 Device | A standardized, sterile fabricated ecosystem used for highly reproducible plant growth and microbiome studies, minimizing environmental variability [50]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Species Identification & Metabolomics

1. Problem: Low Identification Confidence in Metabolomics

- Question: "My LC-MS/MS data shows thousands of peaks, but I can only confidently identify a small fraction. How can I improve this, or alternatively, how can I analyze my data without full identification?"

- Investigation: This is a common challenge, as over 85% of metabolite features in typical plant LC-MS datasets remain unidentified, often referred to as "dark matter" [2]. The limitation is often due to the trade-off between identification accuracy and coverage in existing approaches and the vast, undocumented structural diversity of plant metabolites [2].

- Solution: Adopt a dual-path strategy.

- Path A: Enhance Identification: Utilize advanced artificial intelligence/machine learning-based tools like CSI-FingerID (for compound structure prediction) and CANOPUS (for structural class prediction) based on MS/MS fragmentation data [2]. These tools can classify metabolites into a structural ontology (e.g., Kingdom, Superclass, Class), significantly improving annotation coverage over spectral matching alone [2].

- Path B: Identification-Free Analysis: For biological interpretation, employ techniques that do not require full metabolite identification. These include:

2. Problem: Inconsistent Results from Automated Plant Identification Systems

- Question: "The deep learning model for plant species identification performs well in testing but shows reduced accuracy in real-time field use with a mobile application. What could be the cause?"

- Investigation: A system designed for medicinal plant identification in Borneo achieved 87% Top-1 accuracy on a test set but saw a drop to 78.5% Top-1 accuracy during real-time testing [51]. This performance gap is frequently linked to a mismatch between training data and real-world testing conditions.

- Solution:

- Improve Training Data Diversity: Ensure the training dataset includes images captured in various field conditions, with complex backgrounds, different lighting, and at multiple growth stages, rather than only clean images against a white background [51].

- Implement a Feedback Loop: Integrate a crowdsourcing feature within the application, allowing end-users to provide feedback on identification results. This feedback can be used to enrich the system's knowledge base and continuously retrain and improve the model [51].

3. Problem: Suspected Adulteration or Misidentification of Herbal Material

- Question: "How can I verify the authenticity of an herbal drug and check for adulteration?"

- Investigation: The accurate identification of botanical material is fundamental, as different species or plant parts can have varying therapeutic properties and safety profiles [52]. Incorrect identification can lead to product inefficacy or safety risks.

- Solution: Implement a multi-method authenticity testing protocol [52] [53]:

- Macroscopic and Microscopic Examination: The first step for physical and anatomical characterization.

- Chemical Profiling:

- Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC): A rapid and cost-effective method for obtaining a characteristic fingerprint.

- High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC): Provides a more detailed quantitative profile of key active compounds or markers.

- DNA Barcoding: A powerful technique for genetic authentication of the plant species, which is highly specific and not influenced by growth conditions or plant part [52].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the essential steps for ensuring reproducible sample preparation in plant metabolomics?

- Answer: Reproducibility begins with rigorous sample collection and preparation.

- Collection: Snap-freeze plant tissue immediately after collection in liquid nitrogen to halt metabolic activity. Store consistently at -80°C [54].

- Normalization: Normalize sample amounts based on a consistent metric, such as total protein content or precise tissue weight, to ensure accurate comparisons [54].

- Quality Control (QC) Samples: Prepare and analyze pooled QC samples throughout your batch run. These are used to monitor instrument performance, correct for signal drift, and assess overall data quality [55].

- Internal Standards: Use a suite of isotopically-labeled internal standards (e.g., 5-10 for targeted panels) to correct for variations in extraction efficiency and instrument response [55].

Q2: What metrics should I use to validate the quality of my metabolomics data?

- Answer: Key performance indicators for data quality include:

- Coefficient of Variation (CV): Assess the precision of technical replicates. A CV below 10% is generally indicative of good stability. Both intraday and interday precision should be monitored [55].

- Recovery Rate: This measures extraction efficiency. Ideally, recovery rates should be above 70%, with many reliable methods achieving 80-120% for specific metabolites [55].

- Data Stability: The use of QC samples allows for the measurement of data stability across the entire acquisition batch, ensuring that the analytical system performed consistently.

Q3: Beyond single-marker analysis, what are modern approaches for standardizing herbal medication products?

- Answer: Modern quality control is shifting from single-marker analysis to multi-component assessment.

- Metabolic Fingerprinting: Use advanced analytical platforms like LC-MS, GC-MS, and NMR to generate comprehensive metabolic profiles or "fingerprints" of authentic reference materials [35].

- Multivariate Statistics: Apply methods like Principal Components Analysis (PCA) to compare the fingerprint of test samples against the reference. This allows for the detection of adulteration, contamination, and batch-to-batch inconsistencies based on the overall compositional profile, not just a single compound [35].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Aim: To accurately identify and verify the botanical species of an herbal drug sample. Methodology:

- Macroscopic Examination: Visually inspect the sample for morphological characteristics (e.g., shape, size, color, surface texture).

- Microscopic Examination: Analyze the powdered or sectioned material for unique cellular structures (e.g., trichomes, stomata, calcium oxalate crystals).

- Chemical Profiling:

- Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC): Extract the sample with a suitable solvent. Spot the extract on a TLC plate alongside a reference standard. Develop the plate in an appropriate mobile phase. Visualize under UV light or using a derivatizing reagent. Compare the banding pattern (fingerprint) of the sample to the reference.

- High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC): Prepare a methanolic or hydroalcoholic extract. Separate compounds using a C18 column and a water-acetonitrile gradient. Detect using a UV-Vis or Mass Spectrometer detector. Quantify the levels of one or more key marker compounds against reference standards.

- DNA Barcoding: Extract genomic DNA. Amplify a standard barcode region (e.g., ITS2, rbcL) via PCR. Sequence the amplified product and compare against a curated database of authentic sequences.

Aim: To ensure the reliability, reproducibility, and accuracy of untargeted plant metabolomics data. Methodology:

- Sample Preparation:

- Homogenize frozen plant tissue under liquid nitrogen.

- Extract metabolites using a pre-chilled methanol/water or methanol/chloroform solvent system.

- Centrifuge and collect the supernatant.

- Critical Step: Include a pooled QC sample created by combining a small aliquot from every experimental sample.

- Instrumental Analysis:

- Analyze samples using UHPLC-HRMS (Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry) in both positive and negative ionization modes.

- Critical Step: Inject the pooled QC sample at the beginning of the run for system conditioning, and then repeatedly at regular intervals (e.g., every 6-10 experimental samples) throughout the acquisition batch.

- Data Processing & Quality Assessment:

- Process raw data using metabolomics software (e.g., MS-DIAL, XCMS) for peak picking, alignment, and annotation.

- Assess Data Quality: Calculate the CV for all peaks detected in the QC injections. Features with a CV exceeding 20-30% are typically considered too variable and should be filtered out.

- Correct for Batch Effects: Use statistical methods (e.g., Combat, LOESS regression) to normalize the data based on the stable signals from the repeated QC samples.

Table 1: Key Performance Indicators in Metabolomics Quality Control

| Metric | Target Value | Purpose & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Coefficient of Variation (CV) in QC samples | < 20-30% (lower is better) | Measures the analytical precision of the platform. A low CV indicates stable instrument performance and reproducible data [55]. |

| Recovery Rate | > 70% (Ideal: 80-120%) | Validates the efficiency of the sample preparation and extraction method for specific metabolites [55]. |

| Number of Internal Standards | Typically 5-10 for targeted panels | Corrects for losses during sample preparation and variations in instrument response, ensuring accurate quantification [55]. |

| Detection Limit | Femtogram level (High-Resolution MS) | The lowest concentration at which a metabolite can be reliably detected, crucial for finding low-abundance compounds [55]. |

| Scenario | Model | Top-1 Accuracy | Top-5 Accuracy | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controlled Test Set | EfficientNet-B1 | 87% (private dataset) | N/A | Demonstrates high potential of deep learning models under ideal conditions. |

| Controlled Test Set | EfficientNet-B1 | 84% (public dataset) | N/A | Model generalizes well across different datasets. |

| Real-Time Mobile App | EfficientNet-B1 | 78.5% | 82.6% | Accuracy drop highlights the challenge of variable field conditions (lighting, background, leaf health). |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Quality Control and Metabolomics

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Chemical Reference Standards | Pure compounds used for the definitive identification (MSI Level 1) and quantification of metabolites in herbal materials [52] [53]. |