A Beginner's Guide to Plant Metabolomic Data Analysis: From Raw Data to Biological Insights

This guide provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers and scientists embarking on plant metabolomic data analysis.

A Beginner's Guide to Plant Metabolomic Data Analysis: From Raw Data to Biological Insights

Abstract

This guide provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers and scientists embarking on plant metabolomic data analysis. It covers the entire workflow from foundational concepts and experimental design to advanced computational methods and biological interpretation. Readers will learn about major analytical platforms, data processing tools, statistical techniques, and pathway analysis methods specifically tailored for plant systems. The content addresses common challenges in metabolite identification and data validation, with practical troubleshooting strategies and real-world applications in stress biology, crop improvement, and drug discovery. This resource empowers researchers to transform complex spectral data into meaningful biological knowledge.

Understanding Plant Metabolomics Fundamentals and Experimental Design

Plant metabolomics, a cornerstone of systems biology, aims to provide a comprehensive examination of all low-molecular-weight metabolites within plant systems [1]. However, this field confronts a staggering reality: the plant kingdom is estimated to produce over a million distinct metabolites, yet the vast majority remain chemically uncharacterized [2] [1]. Current databases, such as the KNApSAcK plant metabolite database, have documented only approximately 63,723 compounds as of August 2024, representing a mere fraction of the predicted phytochemical diversity [2]. In practical terms, untargeted liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) studies can typically annotate only 2–15% of detected metabolite peaks to a confident level using standard spectral library matching, leaving over 85% of the metabolome as "dark matter" [2]. This identification bottleneck critically limits our ability to fully understand the diversity, functions, and evolution of plant metabolites, representing a fundamental challenge for researchers initiating plant metabolomic data analysis.

Fundamental Challenges in Plant Metabolite Identification

The Inherent Complexity of Plant Metabolism

The profound challenge of complete metabolome identification originates from several intrinsic properties of plant metabolic networks. Plants synthesize a tremendous number of metabolites—diversified in both structure and abundance—as a survival strategy in response to internal and external stimuli [2]. This metabolic output is categorized into primary metabolites, essential for normal growth and development (e.g., sugars, amino acids, organic acids), and secondary metabolites, crucial for plant-environment interactions (e.g., alkaloids, flavonoids, terpenoids) [3] [1]. The structural diversity within these groups is immense, further complicated by the fact that plant metabolism fluctuates significantly based on genetic factors, physiological status, and environmental conditions [1]. This dynamic nature means the metabolome is not a static entity but a highly responsive system, increasing the analytical complexity for researchers.

Technical and Analytical Limitations

Limitations of Analytical Platforms

No single analytical platform can capture the entire plant metabolome due to the vast physiochemical diversity of metabolites [3]. The table below summarizes the primary techniques used and their respective limitations.

Table 1: Key Analytical Platforms in Plant Metabolomics and Their Limitations

| Analytical Platform | Key Applications | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) | Detection of semi-polar and non-volatile compounds; primary method for untargeted analysis [2]. | Cannot detect all metabolite classes equally well; requires different chromatographic methods for different compounds [1]. |

| Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) | Analysis of volatile compounds or those made volatile by derivatization; excellent for primary metabolites [3]. | Derivatization process is required, leaving underivatized compounds unnoticed [3]. |

| Capillary Electrophoresis-Mass Spectrometry (CE-MS) | High-resolution separation of charged, polar, and hydrophobic analytes [3]. | Less commonly established in standard workflows compared to LC-MS and GC-MS. |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Considered the gold standard for definitive structural elucidation [2]. | Lower sensitivity compared to MS; requires purification of compounds to a high degree, creating a significant bottleneck [2]. |

The Metabolite Annotation Bottleneck

The standard workflow for metabolite identification involves matching experimental data from LC-MS—specifically high-resolution monoisotopic mass and MS/MS fragmentation spectra—against reference libraries [2]. However, this process is severely constrained. General spectral libraries like METLIN and MassBank are enriched with biomedically relevant compounds (e.g., drugs, human hormones) and have limited coverage of plant-specialized metabolites [2]. While specialized plant databases such as RefMetaPlant and the Plant Metabolome Hub (PMhub) are emerging, their coverage remains incomplete relative to total phytochemical diversity [2]. This creates a persistent trade-off between identification accuracy and coverage, where increasing one typically sacrifices the other.

Experimental Workflows and Methodologies

Standard Untargeted Metabolomics Workflow

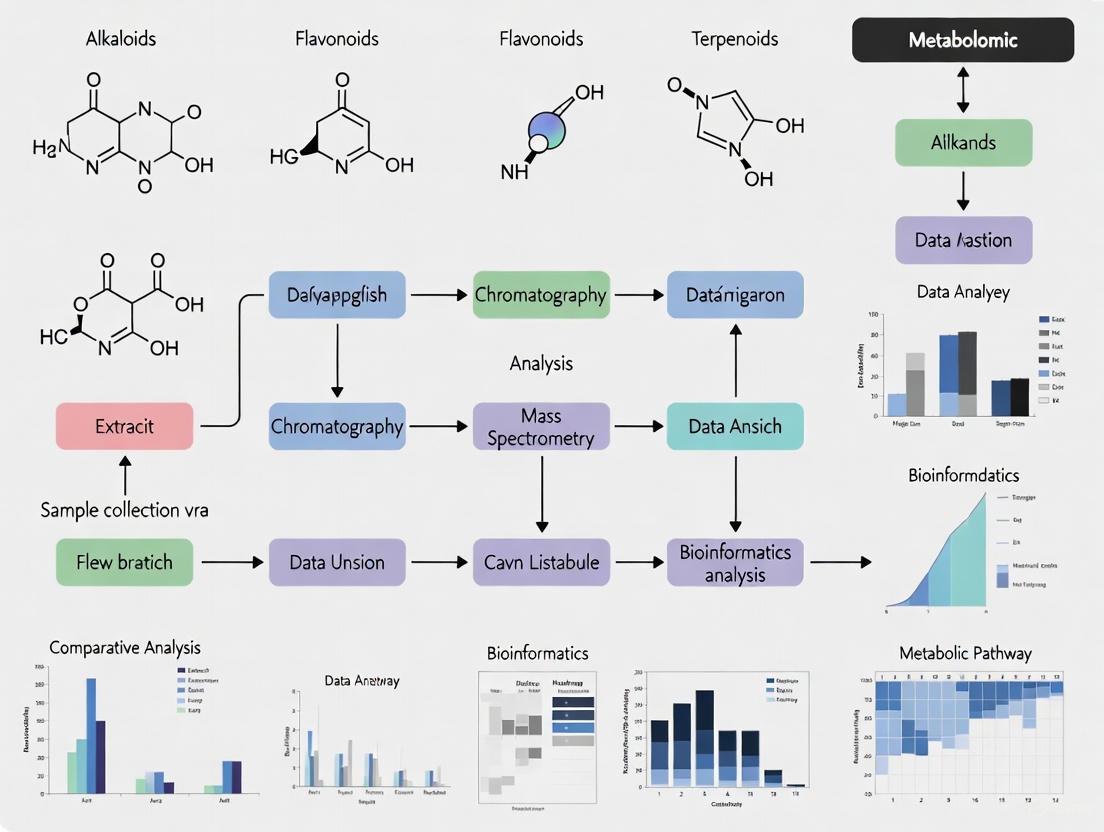

A typical untargeted metabolomics study involves a multi-stage process from sample preparation to biological interpretation. The following diagram outlines the key steps and the points where the identification bottleneck occurs.

Figure 1: Untargeted Metabolomics Workflow. The metabolite annotation stage represents the major bottleneck where over 85% of features remain unidentified [2].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of a plant metabolomics experiment requires specific reagents and computational tools. The following table details essential components of the researcher's toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Plant Metabolomics

| Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Platforms | LC-MS, GC-MS, NMR, CE-MS [3] | High-throughput separation, detection, and quantification of metabolites in complex plant extracts. |

| Spectral Libraries | METLIN, MassBank, GNPS, RefMetaPlant, PMhub [2] | Reference databases for matching experimental MS/MS spectra to annotate metabolite structures. |

| In Silico Tools | CSI-FingerID, CANOPUS, Mass2SMILES [2] | Machine learning tools to predict compound structures or classes from MS/MS fragmentation patterns. |

| Data Processing Software | MET-COFEA, MET-Align, ChromaTOF [3] | Software for raw data preprocessing: baseline correction, peak alignment, and normalization. |

| Statistical Analysis Platforms | MetaboAnalyst 5.0, Cytoscape 3.10.1 [3] | Platforms for performing statistical analysis to identify differentially abundant metabolites and visualize data. |

Strategies for Analysis Amidst Identification Gaps

Advanced Annotation Strategies

To address the annotation challenge, researchers are increasingly turning to computational methods. Artificial intelligence and machine learning-based tools such as CSI-FingerID and CANOPUS can predict molecular structures or classify compounds into ontological classes (e.g., Kingdom, Superclass, Class) based solely on MS/MS fragmentation data, representing a significant advance over pure spectral matching [2]. For instance, CANOPUS was used to annotate metabolites at the Superclass level for approximately 25% of features in a study of Malpighiaceae species, a marked improvement over unidentified data [2]. Rule-based fragmentation represents another strategy, successfully annotating specific metabolite classes like flavonoids and resin glycosides without fully identifying each compound, thereby illuminating aspects of the "dark matter" of metabolomics [2].

Identification-Free Analysis Approaches

Given the identification bottleneck, powerful "identification-free" methods have been developed to extract biological insights from LC-MS datasets without requiring metabolite annotation. These methods enable researchers to visualize metabolic patterns, track changes, and reveal relationships within metabolic networks.

Figure 2: Identification-Free Data Analysis Strategies. These methods allow for biological interpretation even when most metabolites are unidentified [2].

As illustrated in Figure 2, these approaches include:

- Molecular Networking: Groups metabolites based on spectral similarity, often revealing structurally related compounds.

- Distance-Based Approaches (e.g., PCA, Hierarchical Clustering): Visualizes overall metabolic differences between sample groups (e.g., species, treatments) [4].

- Information Theory-Based Metrics: Provides measures of metabolic diversity and richness.

- Discriminant Analysis: Pinpoints metabolite features that best discriminate between sample groups.

A study on three Brassicaceae oilseed crops (Brassica napus, Camelina sativa, and field pennycress) effectively used untargeted metabolomics with LC-MS, detecting thousands of metabolites [4]. By applying hierarchical clustering and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to 718 classified metabolites, the researchers could clearly distinguish the metabolic profiles of the three species without identifying all compounds, demonstrating the utility of these identification-free methods [4].

The challenge of identifying over 85% of plant metabolites is a central issue in plant sciences. This bottleneck stems from the immense structural diversity of plant metabolites, technical limitations of any single analytical platform, and the incomplete coverage of existing metabolite databases. For researchers beginning plant metabolomic data analysis, the path forward involves a dual approach: leveraging advanced computational tools like machine learning to improve annotation rates, while simultaneously employing identification-free analytical strategies to extract meaningful biological patterns from the vast unknown metabolome. Initiatives aimed at expanding shared spectral and metabolite databases, along with the development of more sensitive analytical techniques and powerful bioinformatics, are crucial for illuminating the dark matter of plant metabolism and fully unlocking the functional insights contained within plant metabolomic data.

Plant metabolomics, the comprehensive study of small molecules within plant systems, faces the unique challenge of capturing immense phytochemical diversity. It is estimated that the plant kingdom contains over a million metabolites, yet only a fraction—approximately 63,723 compounds as documented in the KNApSAcK database—have been formally identified [2]. This identification gap presents a significant bottleneck for researchers initiating studies in plant metabolic analysis. The core technological platforms for separating, detecting, and identifying these metabolites are Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS), Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS), and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [5] [6]. Each platform offers distinct advantages and limitations, making platform selection a critical first step in experimental design. This guide provides an in-depth technical comparison of these platforms to inform researchers embarking on plant metabolomics research.

The fundamental challenge in plant metabolomics stems from the vast structural diversity of plant metabolites, which include compounds varying widely in polarity, molecular weight, volatility, and concentration [5]. No single analytical technique can comprehensively cover the entire plant metabolome, necessitating platform selection based on specific research questions [5] [6]. LC-MS has gained prominence for its broad coverage and high sensitivity, GC-MS excels in analyzing volatile compounds, and NMR provides unparalleled structural information and quantitative robustness [5] [6]. Understanding the technical capabilities, requirements, and limitations of each platform is therefore essential for generating biologically meaningful data in plant metabolomics.

Technical Comparison of Major Platforms

The following table provides a quantitative comparison of the three primary analytical platforms used in plant metabolomics, highlighting their key performance characteristics and typical applications.

Table 1: Technical comparison of LC-MS, GC-MS, and NMR platforms for plant metabolomics

| Parameter | LC-MS | GC-MS | NMR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 10⁻¹⁵ mol [6] | 10⁻¹² mol [6] | 10⁻⁶ mol [6] |

| Key Strengths | High sensitivity, broad metabolite coverage, suitable for non-volatile and thermally labile compounds [6] | High sensitivity, universal databases, high separation efficiency [6] | Non-destructive, highly quantitative, provides definitive structural information, high reproducibility [6] |

| Major Limitations | Database dependency, matrix effects can suppress ionization [2] [6] | Limited to volatile or derivatizable compounds, complex sample preparation [6] | Low sensitivity, limited dynamic range, high instrument cost [6] |

| Ionization Source | Electrospray Ionization (ESI), Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) [6] | Electron Impact (EI) [6] | Not Applicable |

| Throughput | High | High | Moderate |

| Metabolite Classes Detected | Lipids, amino acids, flavonoids, anthocyanins, terpenoids, alkaloids [2] [6] | Low polarity metabolites, volatile compounds, organic acids, sugars, fatty acids (after derivatization) [6] | All classes detectable, but limited to most abundant metabolites |

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS)

LC-MS has become a cornerstone technique in plant metabolomics due to its exceptional sensitivity and ability to analyze a wide range of metabolites without the need for derivatization [7] [6]. The technique separates compounds in a liquid phase using high-pressure chromatography, exploiting the hydrophilic and hydrophobic properties of metabolites [6]. Separation is typically achieved using reversed-phase (RPLC) or hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) to cover different polarity ranges [5]. The separated analytes are then ionized, most commonly via Electrospray Ionization (ESI) or Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI), before being introduced into the mass spectrometer for detection [6].

A significant challenge in LC-MS-based plant metabolomics is the high rate of unidentified features. Untargeted LC-MS analyses typically detect thousands of peaks, yet over 85% remain unidentified, often referred to as "dark matter" of metabolomics [2]. To address this, researchers employ annotation strategies using in-house spectral libraries, public databases like GNPS, MassBank, and RefMetaPlant, and increasingly, machine learning tools such as CSI-FingerID and CANOPUS for structural prediction [2]. LC-MS is particularly valuable in discovery-based research where the goal is to comprehensively capture metabolic changes in response to genetic modifications, environmental stresses, or developmental stages in plants [2] [5].

Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS)

GC-MS is one of the earliest analytical techniques applied in metabolomics and remains highly valuable for analyzing volatile and thermally stable metabolites [5] [6]. In GC-MS, the mobile phase is an inert gas (e.g., helium), and separation occurs in a long chromatographic column with temperature programming to optimize the separation of different compounds [6]. A critical requirement for GC-MS analysis is that metabolites must be volatile, which often necessitates chemical derivatization for non-volatile compounds like sugars, organic acids, and some amino acids [5] [6]. This derivatization step adds complexity to sample preparation but enables the analysis of a broader range of metabolites.

The mass spectrometry component in GC-MS typically uses Electron Impact (EI) ionization, a "hard" ionization method that generates reproducible fragment ions [6]. A key advantage of EI is that it produces standardized, platform-independent fragmentation patterns, which has led to the development of extensive, universal spectral libraries [6]. This makes compound identification more straightforward compared to LC-MS. GC-MS is particularly well-suited for targeted analyses of primary metabolites, including organic acids, sugars, sugar alcohols, amino acids, and certain phytohormones [5]. The high separation efficiency and sensitivity of GC-MS make it ideal for profiling central metabolic pathways in plants.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy

NMR spectroscopy provides a fundamentally different approach to metabolomic analysis, relying on the magnetic properties of atomic nuclei rather than mass-based separation [5] [6]. NMR is considered the gold standard for definitive structural elucidation of unknown metabolites and requires minimal sample preparation compared to MS-based techniques [2] [5]. The non-destructive nature of NMR allows for the same sample to be analyzed multiple times or used for subsequent analyses with other platforms [6]. NMR also provides highly reproducible and inherently quantitative data without the need for compound-specific calibration curves [8].

The primary limitation of NMR is its relatively low sensitivity compared to MS-based methods, typically restricting detection to medium- to high-abundance metabolites (concentrations >1 μM) in complex mixtures [5]. This sensitivity constraint often makes NMR less suitable for detecting low-abundance signaling molecules or comprehensive untargeted profiling of complex plant extracts. However, NMR excels in targeted quantification of known metabolites and in applications where non-destructive analysis is paramount [5]. Recent advancements in cryoprobes and higher field strengths are gradually improving NMR sensitivity, expanding its utility in plant metabolomics [5].

Experimental Workflows and Methodologies

Generalized Sample Preparation Protocol

Proper sample preparation is critical for generating reliable metabolomics data. While specific protocols vary depending on the plant matrix and analytical platform, the following represents a generalized workflow:

- Harvesting and Quenching: Rapidly harvest plant tissue (e.g., leaf, root) and immediately quench metabolism using liquid nitrogen to prevent metabolic changes.

- Homogenization: Grind frozen tissue to a fine powder under liquid nitrogen using a mortar and pestle or a bead mill.

- Metabolite Extraction: Add a pre-cooled extraction solvent. Common choices include:

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the extract to pellet insoluble debris.

- Collection and Concentration: Collect the supernatant and optionally concentrate it under a gentle stream of nitrogen or by vacuum centrifugation.

- Reconstitution and Analysis: Reconstitute the extract in a solvent compatible with the chosen analytical platform:

Platform-Specific Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core experimental and data processing workflows for each platform, highlighting critical decision points and processes unique to each technology.

Diagram 1: LC-MS workflow for plant metabolomics

Diagram 2: GC-MS workflow for plant metabolomics

Diagram 3: NMR workflow for plant metabolomics

Successful plant metabolomics research relies on a suite of computational tools and databases for data processing, analysis, and interpretation. The following table catalogs key resources available to researchers.

Table 2: Essential computational tools and databases for plant metabolomics data analysis

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Application in Plant Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| MetaboAnalyst [9] [10] | Web-based Platform | Comprehensive statistical, functional, and pathway analysis of metabolomic data. | Processing LC-MS/GC-MS data, biomarker analysis, pathway mapping for plant systems. |

| GNPS [2] | Spectral Database & Analysis Platform | Molecular networking and spectral library matching for MS/MS data. | Annotation of unknown plant metabolites by spectral similarity. |

| XCMS [8] | Software Tool | Peak detection, alignment, and retention time correction for LC-MS data. | Preprocessing raw LC-MS data from plant extracts for statistical analysis. |

| SIRIUS/CSI:FingerID [2] | Software Tool | De novo annotation of MS/MS spectra using machine learning. | Predicting molecular structures for uncharacterized plant metabolites. |

| CANOPUS [2] | Software Tool | Predicts compound class from MS/MS data without identification. | Functional annotation of untargeted plant metabolomics data. |

| KNApSAcK [2] | Metabolite Database | Comprehensive species-metabolite relationship database. | Identifying known metabolites in specific plant species. |

| RefMetaPlant [2] | Metabolite Database | Plant-specific reference metabolome database with MS/MS spectra. | Annotation of plant-specific metabolic pathways. |

| CFM-ID [10] | Web Tool | In silico fragmentation and metabolite identification from MS/MS spectra. | Annotating unknown peaks in plant LC-MS/MS datasets. |

Selecting the appropriate analytical platform for plant metabolomics research requires careful consideration of the biological question, the chemical nature of the metabolites of interest, and available resources. LC-MS offers the broadest coverage for untargeted discovery, making it ideal for exploring unknown phytochemical diversity. GC-MS provides robust, reproducible analysis of primary metabolism and volatile compounds. NMR delivers definitive structural identification and is excellent for targeted quantification and tracking isotope flow in metabolic flux studies.

Increasingly, integrated approaches that combine multiple platforms provide the most comprehensive view of the plant metabolome. For instance, researchers might use LC-MS for broad untargeted screening followed by GC-MS for precise quantification of central metabolites and NMR for definitive structural elucidation of key unknowns. Furthermore, the growing adoption of machine learning tools for metabolite annotation is helping to illuminate the "dark matter" of metabolomics, opening new frontiers in understanding the diversity, functions, and evolution of plant metabolites [2]. By strategically leveraging these complementary platforms and computational resources, researchers can effectively navigate the complexity of plant metabolic networks and generate meaningful biological insights.

Plant metabolomics has emerged as a crucial component of systems biology, providing comprehensive analysis of the diverse small molecules within plant systems. With plants estimated to produce over 200,000 metabolites, and individual species containing between 7,000-15,000 different compounds, the complexity of plant metabolomes presents unique challenges for researchers [11]. The quality of insights gained from plant metabolomics studies depends fundamentally on the experimental design implemented from the very beginning of the research process. Proper experimental design serves as the critical bridge between biological questions and meaningful data, ensuring that results are both statistically valid and biologically relevant [12].

The importance of robust experimental design has become increasingly apparent as plant metabolomics applications expand across diverse fields. From improving crop resilience to abiotic stresses like drought and salinity [13] to authenticating Chinese medicinal materials [14], from advancing breeding programs [15] to understanding phosphorus deficiency responses in soybean [16], the reliability of metabolomic findings hinges on appropriate design principles. This technical guide outlines the core experimental design principles that underpin successful plant metabolomics research, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework from sample collection to quality control strategies.

Foundational Experimental Design Considerations

Defining Clear Research Hypotheses and Objectives

A well-defined research hypothesis (RH) forms the cornerstone of any successful plant metabolomics study. The hypothesis should be directly linked to the metabolic pathways and metabolites of interest, guiding the selection of appropriate analytical tools and experimental configurations [17]. In practice, this means moving beyond vague questions like "how does stress affect plant metabolism" to more precise formulations such as "how does phosphorus deficiency alter carbon and nitrogen allocation pathways in soybean leaves during reproductive development?" The latter type of hypothesis enables targeted experimental design and appropriate analytical approaches.

Biological relevance must guide technical decisions throughout the experimental planning process. For example, when studying plant responses to environmental stresses, researchers must consider whether the stress application mimics field conditions, whether the sampling timepoints capture critical transition periods, and whether the selected plant tissues are biologically relevant to the processes being studied [13] [16]. These considerations ensure that the resulting data will have meaningful biological interpretation rather than merely representing technical artifacts.

Replication Strategies: Biological vs. Technical

Table 1: Replication Strategies in Plant Metabolomics

| Replication Type | Definition | Purpose | Recommended Minimum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Replicates | Independent biological units (different plants) | Capture biological variation | 6-8 for controlled conditions; 10+ for field studies |

| Technical Replicates | Multiple analyses of same biological sample | Assess technical variability | 3-5 for method validation; 1 for large studies |

| Procedure Replicates | Repeated sample preparations from same material | Evaluate preparation consistency | 3 for method development |

| Instrument Replicates | Repeated injections on same instrument | Monitor instrument stability | Quality control samples |

A crucial distinction in experimental design lies between biological and technical replication. Biological replicates are independent biological units (e.g., different plants) randomly and independently selected to represent their larger population, while technical replicates involve repeated measurements of the same biological sample [12]. The number of biological replicates is the primary determinant of statistical power in metabolomics studies, as it directly affects the ability to detect biologically meaningful differences amidst natural variation.

Pseudoreplication represents a common experimental design error that occurs when researchers mistake multiple measurements from non-independent sources as true replicates [12]. Examples include sampling different leaves from the same plant without proper randomization or pooling samples from multiple plants before analysis and treating the pooled samples as replicates. Proper experimental design requires clearly defining biological units (BUs), experimental units (EUs), and observational units (OUs) to avoid pseudoreplication and ensure accurate data interpretation [17].

Randomization and Blocking Strategies

Randomization serves two critical functions in experimental design: preventing the influence of confounding factors and enabling rigorous testing of interactions between variables [12]. In practice, randomization should be applied to the order of sample collection, treatment applications, and analytical sequences to distribute systematic effects evenly across experimental groups. For example, when collecting samples across multiple days, researchers should randomly assign treatments to collection days rather than processing all control samples on one day and treatment samples on another.

Blocking represents a powerful strategy for minimizing noise when known sources of variability exist. In plant metabolomics, blocking factors might include growth chamber position, harvest time batches, or sample preparation dates. By grouping similar experimental units together in blocks and applying treatments randomly within each block, researchers can account for these variability sources while maintaining the ability to detect treatment effects [12]. For instance, when processing large sample sets across multiple days, a complete block design with balanced treatments processed each day prevents day-to-day variation from confounding treatment effects.

Sample Collection and Preparation Protocols

Systematic Sample Collection Framework

Table 2: Sample Collection and Stabilization Guidelines

| Step | Key Considerations | Recommended Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Harvesting | Consistent timing, tissue selection, developmental stage | Rapid harvesting; consistent timing across replicates |

| Quenching | Immediate halting of metabolic activity | Flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen; cold methanol for specific applications |

| Storage | Preservation of metabolic profile | -80°C; avoid freeze-thaw cycles; transport on dry ice |

| Homogenization | Uniform powder without thawing | Cryogenic grinding with mortar/pestle or bead beaters; pre-cooled equipment |

| Documentation | Tracking metadata | Standardized recording of growth conditions, harvest time, processing details |

Proper sample collection begins with a carefully considered harvesting strategy that accounts for biological factors known to influence metabolism. These include diurnal rhythms, developmental stage, tissue specificity, and environmental conditions at the time of collection [17]. For time-course studies, sample collection should occur at consistent times throughout the day to avoid confounding treatment effects with diurnal variation. When studying plant responses to environmental stresses, researchers must standardize environmental and growth conditions across all experimental units to minimize extraneous variation [16].

The quenching process must immediately halt metabolic activity to preserve the metabolic profile at the time of collection. Flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen represents the gold standard for most plant metabolomics applications [13]. Storage conditions must maintain metabolic stability, with -80°C storage recommended for most applications. Proper documentation throughout collection ensures traceability and enables later identification of potential confounding factors.

Metabolite Extraction Methodologies

Selection of appropriate extraction methods represents one of the most critical decisions in sample preparation, directly influencing the range and quality of metabolites detected. The chemical diversity of plant metabolites necessitates extraction protocols capable of capturing compounds across a wide polarity range, from polar sugars and amino acids to non-polar lipids and secondary metabolites [17].

Figure 1: Metabolite Extraction Decision Framework

For untargeted metabolomics, which aims to capture as many metabolites as possible, multi-phase extraction systems like methanol:chloroform:water provide broad coverage across compound classes [17]. Targeted approaches focusing on specific metabolite classes (e.g., lipids, phenolics, volatiles) benefit from optimized single-phase extraction systems selective for those compounds. The choice of extraction method must align with both the analytical platform and the research objectives, recognizing that no single extraction method can comprehensively cover the entire plant metabolome [17].

Analytical Platform Selection and Configuration

Comparative Platform Characteristics

Table 3: Analytical Platform Selection Guide

| Feature | GC-MS | LC-MS | NMR Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | High | Very high | Moderate |

| Reproducibility | High | Moderate–high | Very high |

| Sample Preparation | Requires derivatization | No derivatization needed | Minimal |

| Metabolite Coverage | Volatile, polar metabolites | Broad (polar and non-polar) | Limited, mostly abundant metabolites |

| Quantification | Relative or absolute (with standards) | Relative or absolute (with standards) | Absolute without standards |

| Structural Elucidation | Limited | Limited to fragmentation data | Strong (direct molecular structure) |

| Destructive Analysis | Yes | Yes | No |

| Throughput | Moderate | High | Moderate |

| Common Applications | Sugars, amino acids, organic acids | Secondary metabolites, lipids, phenolics | Structural ID, metabolite fingerprinting |

Selection of appropriate analytical platforms represents a critical decision point in experimental design, with each major platform offering distinct advantages and limitations. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) provides high sensitivity and reproducibility for volatile and thermally stable compounds, particularly primary metabolites like sugars, amino acids, and organic acids [13]. Derivatization extends its application to non-volatile compounds but introduces additional complexity. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) offers exceptional versatility in analyzing both polar and non-polar compounds without derivatization, making it ideal for secondary metabolite analysis [13] [11]. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, while less sensitive than MS-based techniques, provides unparalleled structural information and absolute quantification without requiring standards [13].

Many sophisticated plant metabolomics studies employ complementary orthogonal approaches to overcome the limitations of individual platforms [17]. For example, combining GC-MS for primary metabolism with LC-MS for secondary metabolism provides comprehensive coverage of biochemical pathways. Similarly, integrating NMR with MS platforms leverages NMR's structural capabilities alongside MS's sensitivity. The choice of platform must consider the specific research questions, required metabolite coverage, available resources, and expertise in data interpretation.

Platform-Specific Experimental Considerations

Each analytical platform requires specific experimental design considerations. For GC-MS studies, researchers must account for derivatization efficiency and stability, potential formation of multiple derivatives for some metabolites, and the thermal stability of compounds of interest [13]. LC-MS methods require careful selection of chromatographic columns, mobile phases, and ionization modes based on the chemical properties of target metabolites. NMR experiments need optimization of pulse sequences, solvent suppression, and acquisition parameters to maximize sensitivity and resolution [13].

Ion suppression effects in LC-MS represent a particular challenge that can be mitigated through proper chromatographic separation, sample clean-up, and in some cases, stable isotope-labeled internal standards [13]. For all platforms, inclusion of quality control samples—typically pooled samples representing all experimental groups—enables monitoring of instrument performance throughout data acquisition [17]. Randomized sample injection orders help distribute instrument drift evenly across experimental groups, preventing confounding of biological effects with technical variation.

Data Analysis and Quality Control Frameworks

Quality Assurance and Quality Control Strategies

Robust quality assurance (QA) and quality control (QC) protocols form the foundation of reliable plant metabolomics data. The Metabolomics Quality Assurance and Quality Control Consortium (mQACC) provides comprehensive guidelines to enhance data reliability, focusing on aspects including sample preparation consistency, instrument performance monitoring, and data quality assessment [17]. Implementation of systematic QC protocols includes analysis of pooled quality control samples (QCs) at regular intervals throughout analytical sequences, enabling monitoring of instrument stability and data quality.

Quality control samples serve multiple purposes: they assess technical variation, monitor instrument performance drift, and sometimes facilitate signal correction [17]. In practice, QC samples should be injected at the beginning of the sequence for system equilibration, then regularly throughout the sequence (e.g., after every 5-10 experimental samples). Specific QC metrics vary by platform but may include retention time stability, mass accuracy, signal intensity stability, and chromatographic peak shape. Established acceptance criteria for these metrics ensure consistent data quality throughout the acquisition process.

Statistical Design and Power Analysis

Statistical power analysis represents a crucial but often overlooked component of experimental design that helps researchers optimize sample size before commencing large-scale studies. Power analysis calculates the number of biological replicates needed to detect a certain effect size with a specified probability, balancing the risks of false positives (Type I errors) and false negatives (Type II errors) [12]. The five components of power analysis are sample size, expected effect size, within-group variance, false discovery rate, and statistical power.

In practice, researchers typically fix the false discovery rate (often at 5%) and statistical power (often at 80%), then estimate required sample size based on expected effect size and within-group variance [12]. Effect size estimation can draw from pilot studies, comparable published research, or biological first principles. Several specialized tools facilitate sample size determination in metabolomics, including MetSizeR and MetaboAnalyst, which address the high-dimensional data challenges specific to metabolomics studies [17].

Figure 2: Experimental Design Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Plant Metabolomics

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection | Liquid nitrogen, cryogenic gloves, pre-cooled containers, sterile tools | Immediate metabolic quenching, sample integrity |

| Homogenization | Cryogenic mill, mortar and pestle, ceramic beads, liquid nitrogen | Tissue disruption while maintaining metabolic stability |

| Extraction Solvents | HPLC-grade methanol, chloroform, water, MTBE, acetonitrile | Metabolite extraction with minimal degradation |

| Derivatization Reagents | MSTFA, methoxyamine hydrochloride, TMCS | Volatilization of compounds for GC-MS analysis |

| Internal Standards | Stable isotope-labeled compounds (e.g., 13C-sugars, 15N-amino acids) | Quantification normalization, quality control |

| Chromatography | HPLC/UPLC columns (C18, HILIC), guard columns, mobile phase additives | Metabolic separation prior to detection |

| Quality Control | Pooled QC samples, process blanks, standard reference materials | Monitoring technical performance, data quality |

| Data Analysis | Reference spectral libraries (METLIN, MassBank, GNPS) | Metabolite identification and annotation |

The selection of appropriate reagents and materials significantly influences the quality and reproducibility of plant metabolomics data. High-purity solvents minimize background interference and ion suppression effects, particularly in MS-based analyses [17]. Internal standards, especially stable isotope-labeled analogs of endogenous metabolites, enable correction for sample preparation variability and instrument performance fluctuations. For targeted analyses, authentic chemical standards provide essential references for compound identification and absolute quantification.

Reference materials and quality control samples represent particularly crucial components of the metabolomics toolkit. Pooled QC samples, created by combining small aliquots from all experimental samples, provide a representative reference material for monitoring analytical performance [17]. Process blanks help identify contamination sources, while standard reference materials with known concentrations enable assessment of quantitative accuracy. Commercial quality control materials for specific metabolite classes provide benchmarks for method validation and cross-laboratory comparisons.

Experimental design in plant metabolomics represents a multidimensional challenge requiring careful integration of biological, analytical, and statistical principles. From initial hypothesis formulation through sample collection, analytical measurement, and data quality assessment, each decision point influences the validity and reliability of final conclusions. The complex nature of plant metabolomes, with their vast chemical diversity and dynamic responses to environmental cues, necessitates particularly rigorous attention to experimental design principles.

By implementing the systematic approaches outlined in this guide—including appropriate replication and randomization, standardized sample collection protocols, platform-specific analytical considerations, and comprehensive quality control strategies—researchers can generate plant metabolomics data with the robustness required for meaningful biological interpretation. As the field continues to advance with emerging technologies like single-cell metabolomics and spatial mass spectrometry imaging [11], these foundational experimental design principles will remain essential for extracting reliable biological insights from complex metabolic data.

Plant metabolomics, the comprehensive analysis of small molecules within plant systems, is a cornerstone of systems biology. It provides deep insights into the metabolic pathways that underpin plant growth, development, and responses to environmental stresses [3]. Unlike other omics technologies, metabolomics deals with a vast chemical diversity, with estimates suggesting plants collectively produce metabolites numbering in the millions [18]. This tremendous complexity creates a significant challenge: the identification of metabolites from raw instrumental data. This is where metabolite databases and spectral libraries become indispensable. They serve as reference repositories, enabling researchers to translate complex mass spectrometry or NMR data into biologically meaningful identifications. For researchers beginning plant metabolomic data analysis, understanding and selecting the appropriate database is a critical first step, as the choice directly influences the breadth and confidence of metabolite annotation, shaping all subsequent biological interpretation [19].

This guide provides an in-depth introduction to the major plant metabolite databases and spectral libraries, detailing their contents, applications, and the experimental protocols that underpin their construction. Framed within the initial steps of a plant metabolomics research workflow, it is designed to equip researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the knowledge to effectively navigate and utilize these essential resources.

The landscape of plant metabolomics resources has expanded significantly, moving beyond general metabolomics databases to include platforms specifically designed for the unique needs of plant research. These resources can be broadly categorized as reference metabolome databases, which provide a broad overview of metabolites expected in specific plants, and spectral libraries, which contain reference fragmentation patterns for confident compound identification. The following tables summarize the key features of major plant-focused and general resources that are highly relevant to plant science.

Table 1: Major Plant-Specific Metabolome Databases and Spectral Libraries

| Database/Library Name | Type | Key Plant-Specific Features | Number of Metabolites/Spectra | Notable Attributes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMhub (Plant Metabolome Hub) [20] | Integrated Database | Genetic analysis tools (mGWAS, transcriptomic data), metabolic networks, reaction data | 188,837 metabolites; 1,467,041 HRMS/MS spectra | Combines cheminformatics and bioinformatics, includes experimentally detected features from 10 plant species |

| RefMetaPlant (Reference Metabolome Database for Plants) [18] | Reference Metabolome | Reference metabolomes for 153 plant species across five major phyla | Covers a wide range of plant species | Provides a reference metabolome for plants, analogous to a reference genome |

| PCMD (Plant Comparative Metabolomics Database) [21] | Comparative Database | Multilevel comparison of metabolic profiling across 530 plant species | Information on intra- and cross-species metabolic profiling | Facilitates comparative metabolomics on a large scale |

| Bruker MetaboBASE Plant Library [22] | Spectral Library | Spectra from commercial standards and putatively identified metabolites in Medicago truncatula | 228 spectra for 84 compounds | Includes Collisional Cross Section (CCS) values for orthogonal identification |

| Creation of a Plant Metabolite Spectral Library [23] | Spectral Library | Library built with 544 authentic compounds relevant to Arabidopsis | 544 authentic standards | Focus on a curated, plant-specific spectral library (mzVault format) |

Table 2: General Metabolomics Databases with Significant Relevance to Plant Research

| Database/Library Name | Type | Relevance to Plant Metabolomics | Number of Metabolites/Spectra | Notable Attributes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GNPS Library (Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking) [24] | Spectral Library | Contains extensive natural product compounds from user contributions, including phytochemical libraries | Includes PhytoChemical Library (140 compounds), NIH Natural Products Libraries (1000s of spectra) | Community-driven, enables molecular networking and data sharing |

| Bruker MetaboBASE Personal Library 3.0 [22] | Spectral Library | Includes over 100,000 synthetic/isolated standards from METLIN, plus in-silico spectra | >100,000 standard spectra; >233,000 in-silico spectra | Extensive coverage of endogenous and exogenous metabolites |

| NIST Tandem Mass Spectral Library [22] | Spectral Library | Broad coverage of small molecules, includes plant-relevant compounds | 1,320,389 MS/MS spectra from 30,999 compounds | A comprehensive, well-curated general library |

| METLIN [20] [19] | Metabolite Database | One of the earliest and largest metabolite databases, used for mass and isotope pattern matching | Large repository of metabolite information | Often used as a first pass for compound candidate search |

Quantitative Comparison and Selection Guidelines

When selecting a database or library, researchers must consider quantitative metrics of content and quality alongside their specific experimental goals. The following table provides a direct comparison based on key metrics as found in the literature.

Table 3: Quantitative Comparison of Database and Library Contents

| Item | PMhub [20] | KEGG [20] | Plant Metabolic Network (PMN) [20] | Golm Metabolome Database (GMD) [20] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Metabolites | 188,837 | 19,121 | 4,806 | 2,222 |

| Number of Reactions | 348,153 | 11,947 | 5,234 | 0 |

| Number of Standard MS/MS Spectra | 336,844 | 0 | 0 | 11,680 |

| Number of In-silico MS/MS Spectra | 1,130,197 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Number of Experimentally Detected Features | 144,366 | 0 | 0 | 26,590 |

Guidelines for Selection:

- For Untargeted Discovery and Novel Pathway Identification: Use large, integrated databases like PMhub or RefMetaPlant, which offer extensive metabolite lists and tools for connecting metabolites to genetic information and pathways [20] [18].

- For High-Confidence Metabolite Identification: Prioritize spectral libraries built from authentic standards, such as the plant-specific library from [23] or the commercially available Bruker HMDB Metabolite Library 2.0 [22]. The confidence in identification increases with orthogonal data; therefore, libraries that include retention time and CCS values (e.g., Bruker MetaboBASE Plant Library) are highly recommended [22].

- For Natural Products and Specialized Metabolites: Leverage the GNPS platform and its associated phytochemical libraries, which are rich in natural product data and allow for community-driven identification and molecular networking [24].

- For Cross-Species Comparative Metabolomics: Utilize PCMD, which is explicitly designed for multilevel comparison across a vast number of plant species [21].

Experimental Protocols for Spectral Library Creation and Utilization

Protocol: Creating a Custom Plant Metabolite Spectral Library

The creation of a custom spectral library using authentic standards ensures high-confidence identification for targeted or pseudo-targeted metabolomics studies. The following detailed protocol is adapted from the work that created a plant metabolite spectral library with 544 authentic standards [23].

1. Preparation of Authentic Standards: - Compounds: Acquire purified authentic chemical standards from commercial suppliers (e.g., Sigma-Aldrich). - Solubilization: Dissolve each standard to a final concentration of approximately 1 ng/µL. Use water as the primary solvent. For compounds with poor water solubility, use 75% methanol as an alternative [23].

2. LC-MS/MS Data Acquisition for Spectral Generation: - Chromatography: Employ a UHPLC system with a reversed-phase column (e.g., Accucore C18, 2.6 µm 2.1 × 30 mm). Use a mobile phase gradient from 0.1% formic acid and 10 mM ammonium formate in water to 0.1% formic acid and 10 mM ammonium formate in acetonitrile over a 15-minute run [23]. - Mass Spectrometry: Use a high-resolution mass spectrometer (e.g., Orbitrap Q Exactive). - MS1 Parameters: Set resolution to 70,000 (at m/z 200) with positive and negative ion switching. - Data-Dependent MS/MS (dd-MS2): Set MS/MS resolution to 17,500. Use a data-dependent acquisition method to fragment the top ions. Apply stepped normalized collision energies (NCE) to generate comprehensive fragment patterns. The study used NCE settings of 10, 15, 20, 30, 35, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, and 120 eV [23]. - Targeted MS/MS (if needed): For compounds that fail to yield satisfactory MS2 spectra (e.g., fewer than three fragment ions) via dd-MS2, perform reinjections using Targeted Parallel Reaction Monitoring (PRM). Use an inclusion list of precursor m/z values and systematically apply the same range of collision energies [23].

3. Spectral Library Construction: - Data Processing: Process the raw mass spectral files to filter and recalibrate peaks based on theoretical accurate mass. - Spectra Curation: Manually inspect spectra to select the best representative spectrum for each compound. For some compounds, multiple spectra at different energies may be included. - Library Population: Populate the library software (e.g., mzVault, TraceFinder) with the following information for each metabolite: compound name, formula, structure, precursor m/z, retention time, optimized collision energy, and the MS/MS spectrum (including the quantitation ion and at least three confirming fragment ions) [23].

Protocol: Metabolite Identification Using Spectral Libraries

This protocol outlines the standard workflow for identifying metabolites in an untargeted plant metabolomics study by querying experimental data against spectral libraries [19] [23].

1. Feature Extraction and Data Pre-processing: - Convert raw LC-MS/MS files into a data matrix containing mass/retention time features and their intensities. - Perform baseline correction, peak alignment, and normalization to minimize technical variance [19].

2. Database Searching: - MS Database Search: For high-resolution MS1 data, compare the accurately measured neutral mass of a feature against an MS database (e.g., METLIN, PMhub). This generates a list of candidate compounds [19]. - Isotope Pattern Matching: Compare the experimental isotope pattern of the feature with the theoretical pattern of candidate compounds to refine the list and confirm empirical formula [19].

3. Spectral Library Matching: - For each feature, extract its experimental MS/MS spectrum. - Query this experimental spectrum against a curated MS/MS spectral library (e.g., GNPS, Bruker HMDB Library, or a custom plant library). - The software calculates a spectral similarity score (e.g., dot product). A higher score indicates a better match between the experimental and reference spectra, leading to a more confident identification [22] [19]. - Increasing Confidence: For the highest level of confidence, match the experimental data against a library that includes retention time and/or CCS values, providing orthogonal confirmation of the identity [22].

Workflow Visualization for Plant Metabolite Identification

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for identifying plant metabolites, from sample preparation to biological interpretation, highlighting the critical role of databases and spectral libraries.

Plant Metabolite Identification Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting plant metabolomics experiments, particularly those related to the creation and use of spectral libraries.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Plant Metabolomics

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Authentic Chemical Standards | Purified metabolites used to acquire reference MS/MS spectra for library creation or to confirm identities in samples. | Sigma-Aldrich was used as a source for 544 authentic compounds to build a plant spectral library [23]. |

| Internal Standard Mixture | Compounds added to each sample to correct for variability during sample preparation and instrument analysis. | A mixture of lidocaine and 10-camphorsulfonic acid was used in Arabidopsis leaf metabolite extraction [23]. |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents (water, acetonitrile, methanol, isopropanol) to minimize background noise and ion suppression in MS. | Used in metabolite extraction solvents and as mobile phases for UHPLC [23]. |

| Acid Additives | Added to mobile phases to improve chromatographic separation and ionization efficiency (e.g., formic acid, ammonium formate). | 0.1% formic acid and 10 mM ammonium formate were used in the mobile phase for LC-MS analysis [23]. |

| Metabolite Extraction Solvents | Solvent systems designed to efficiently extract a wide range of metabolites with different polarities from plant tissue. | A sequential extraction with solvents of varying polarity (acetonitrile:isopropanol:water; acetonitrile:water; 80% methanol) was employed [23]. |

| Reversed-Phase UHPLC Column | The core component for chromatographic separation of metabolites prior to mass spectrometry. | An Accucore C18, 2.6 µm 2.1 × 30 mm column was used for analysis of authentic standards [23]. |

| Specialized LC Columns | Columns for alternative separation mechanisms, such as HILIC (hydrophilic interaction) for polar compounds. | The protocol tested HILIC and HILIC-IEX columns for method development [23]. |

Basic Statistical Concepts for Metabolomic Data Interpretation

This guide provides plant metabolomics researchers with a foundation in the core statistical concepts and methods essential for robust data interpretation, from initial experimental design to biological insight.

Plant metabolomics involves the comprehensive analysis of small molecules, generating complex, high-dimensional data sets. The core challenge is to extract meaningful biological signals from this inherent variability. Statistical analysis provides the framework to achieve this, separating true biological effects from technical noise and natural physiological variation. In plant science, this is crucial for applications such as differentiating plant species or responses to environmental stress, understanding the effects of genetic modifications, and identifying metabolic markers of traits [25] [26]. The analytical workflow is a cyclic process of discovery, progressing from raw data to biological hypotheses, which in turn guide further analysis and validation.

The following diagram illustrates the core logical workflow for interpreting metabolomic data:

Foundational Statistical Concepts and Methods

A successful metabolomics study rests on a foundation of key statistical concepts tailored to the properties of -omics data.

Data Types and Distributions

Metabolomics data are typically continuous (e.g., peak intensities or concentration values). These data often do not follow a normal (Gaussian) distribution; they are frequently right-skewed, with metabolite concentrations spanning several orders of magnitude [27]. This non-normality must be considered when selecting statistical tests and normalization procedures.

Handling Missing Values and Data Normalization

Missing values are common and are categorized based on their origin [27]. Missing Not At Random (MNAR) often indicates a metabolite's concentration is below the instrument's detection limit. In contrast, Missing At Random (MAR) may be due to technical artifacts like ion suppression.

- Strategies for MNAR: Imputation with a constant value (e.g., 1/2 of the minimum detected value) is a common and often effective strategy [27].

- Strategies for MAR/MCAR: Imputation using k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) or Random Forest methods, which estimate missing values based on similar samples [27].

Data normalization is critical to remove unwanted technical variation (e.g., batch effects, sample-to-sample concentration differences) while preserving biological variation. Common methods include probabilistic quotient normalization, and normalization using quality control (QC) samples [27].

Statistical analysis in metabolomics is stratified into univariate and multivariate approaches, each with distinct purposes.

Table 1: Key Statistical Approaches in Metabolomics

| Analysis Type | Purpose | Common Methods | Use Case in Plant Science |

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Analyze one metabolite at a time to find statistically significant changes between groups. | Student's t-test, ANOVA, Mann-Whitney U test [28] [29]. | Comparing levels of a specific anthocyanin in purple vs. orange-fleshed sweet potatoes [30]. |

| Multivariate | Analyze all metabolites simultaneously to understand global patterns and relationships. | Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) [28] [29]. | Classifying different Ilex species based on their overall metabolic fingerprint [26]. |

| Supervised | A type of multivariate analysis used to build a model that predicts a known class or outcome. | PLS-DA, Random Forests, Support Vector Machines (SVM) [29]. | Discriminating between infected and healthy plants based on their metabolic profiles. |

| Unsupervised | A type of multivariate analysis to find inherent patterns or clusters without prior class labels. | PCA, Hierarchical Clustering [28]. | Exploring natural groupings in samples from different plant organs or under various stress conditions. |

Essential Data Visualization Techniques

Visualization is an integral part of statistical analysis, providing intuitive means to inspect data quality, identify patterns, and communicate findings.

Univariate Analysis Graphs

These plots are used to understand the distribution and significance of individual metabolites.

- Box Plots: Effectively display the distribution (median, quartiles, potential outliers) of a single metabolite's abundance across different sample groups (e.g., treated vs. control plants) [28].

- Volcano Plots: Combine statistical significance (p-value) and magnitude of change (fold-change) to visually identify the most relevant differentially abundant metabolites. Metabolites in the upper-left or upper-right corners are prime candidates for further investigation [31] [28].

Multivariate Analysis Graphs

These visualizations represent the combined information from all measured metabolites.

- PCA Scores Plot: An unsupervised method that reduces data dimensionality to reveal natural sample clustering, trends, or outliers based on the overall metabolic composition [28].

- PLS-DA Scores Plot: A supervised method that maximizes the separation between pre-defined sample groups, helping to identify metabolic patterns that discriminate between conditions [28].

- Hierarchical Clustering Heatmap: Visualizes the relative abundance of all metabolites (rows) across all samples (columns). Samples and metabolites are clustered based on similarity, revealing patterns and co-regulated metabolite groups [28].

Best Practices for Accessible Visualizations

When creating figures, adhere to these guidelines to ensure they are interpretable by all readers, including those with color vision deficiencies [32] [33].

- Do Not Rely on Color Alone: Use patterns, shapes, or direct labels in addition to color to distinguish data series [33].

- Ensure Sufficient Contrast: Aim for a contrast ratio of at least 3:1 for graphical elements and 4.5:1 for text against its background [32].

- Provide Alternative Text: All visualizations should have descriptive alt-text that conveys the key message of the chart [32].

A Practical Workflow for Plant Metabolomics

The statistical journey from raw data to biological insight follows a structured pathway. The diagram below outlines the key stages, showing how raw data is transformed into actionable biological knowledge.

A robust metabolomics analysis relies on a suite of bioinformatics tools and databases.

Table 2: Key Bioinformatics Tools and Databases for Plant Metabolomics

| Tool / Resource | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| XCMS, MS-DIAL | Peak picking, alignment, and preprocessing of mass spectrometry data [29]. | Processing raw LC-MS files from an experiment comparing leaf extracts under drought and normal conditions. |

| MetaboAnalyst | Web-based platform for comprehensive statistical analysis, visualization, and pathway enrichment [27] [29]. | Performing a PCA and generating a volcano plot to identify significantly altered metabolites in transgenic plants. |

| GNPS | Platform for spectral matching and molecular networking via tandem MS data [30] [29]. | Annotating unknown metabolites in a plant extract by comparing MS/MS spectra to public libraries and visualizing chemical similarity. |

| KEGG, PlantCyc | Databases of curated biochemical pathways and metabolites [29]. | Mapping differentially abundant metabolites onto biosynthetic pathways for phenylpropanoids or terpenoids. |

| HMDB, KNApSAcK | Comprehensive metabolite databases; KNApSAcK is specialized for plant species [30] [29]. | Identifying and annotating metabolites detected in a non-model plant species. |

Advanced Topics: From Identification-Free Analysis to Multi-Omics

Given that over 85% of LC-MS peaks in plant studies often remain unidentified, identification-free strategies are powerful alternatives [30]. Methods like molecular networking group metabolites based on spectral similarity, allowing researchers to pinpoint key metabolite signals and interpret global patterns without the bottleneck of full identification [30].

The future of plant metabolomics lies in integration with other omics layers (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics). Statistical methods like O2PLS (Two-Way Orthogonal Partial Least Squares) can be used for combined modeling of transcript and metabolite data, enabling a systems-level understanding of plant biology [30].

Practical Workflow: From Raw Spectral Data to Biological Interpretation

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) has become the predominant analytical platform for global untargeted plant metabolomics, capable of detecting thousands of metabolite features from a single organ extract [34] [2]. The tremendous structural diversity of plant metabolites—with an estimated over one million compounds across the plant kingdom—presents both a tremendous opportunity and a significant bioinformatic challenge [2]. Raw LC-MS data are complex, containing valuable information hidden within substantial chemical noise, baseline drift, and retention time shifts [35] [19]. Data pre-processing serves as the critical first computational step that transforms this raw instrumental data into a structured feature table suitable for biological interpretation, making the choice of pre-processing tools fundamental to all subsequent analyses [35] [36].

The challenge is particularly acute in plant science, where studies routinely detect 10,000-15,000 metabolite features in a single plant species, yet typically only 2-15% can be confidently annotated using current spectral libraries [2] [34]. This vast landscape of "dark matter" in plant metabolomics means that the quality of data pre-processing directly determines our ability to observe true biological patterns within the unresolved chemical complexity [2]. Within this context, three open-source tools—XCMS, MZmine, and MS-DIAL—have emerged as the most widely used platforms for metabolomic data pre-processing, each offering distinct approaches to peak detection, alignment, and annotation within an integrated workflow [35] [37].

Core Pre-processing Workflows: A Comparative Analysis

The fundamental workflow for LC-MS data pre-processing consists of several key stages: feature detection and peak picking, chromatographic alignment, gap filling, and metabolite annotation [35] [19]. While XCMS, MZmine, and MS-DIAL all address these core requirements, they differ significantly in their algorithmic approaches, user interfaces, and specialized capabilities, making each tool uniquely suited to particular research scenarios and user expertise levels [37] [38].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Major Metabolomics Pre-processing Tools

| Tool | Primary Interface | Key Strengths | Plant Metabolomics Applications | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XCMS | R/Bioconductor | High statistical power, extensive algorithm options, seamless integration with downstream statistical analysis | Comprehensive peak detection for diverse metabolite classes; ideal for large-scale studies | [35] [37] |

| MZmine | Desktop GUI | Modular workflow design, support for advanced MS imaging data, flexible parameter optimization | Effective for both targeted and untargeted analysis of specialized plant metabolites | [37] [38] |

| MS-DIAL | Desktop GUI | Integrated lipidomics support, comprehensive DDA/DIA data processing, retention time index calibration | Superior for plant lipidomics and novel metabolite identification through MS/MS spectral deconvolution | [37] [2] |

XCMS: The R-Based Powerhouse

XCMS operates within the R/Bioconductor environment, making it particularly powerful for researchers who require extensive customization and plan to conduct downstream statistical analysis within the same programming environment [35] [37]. Its command-line interface provides access to multiple peak detection and alignment algorithms, allowing experienced users to fine-tune parameters for specific experimental conditions or instrument types [35]. The recently released XCMS3 represents a significant rewrite that improves scalability and incorporates new functionalities for handling large-scale metabolomic datasets [35].

A key advantage of XCMS in plant metabolomics research is its powerful peak detection algorithm based on centWave, which is particularly effective for detecting and quantifying peaks in complex plant metabolic profiles with high chromatographic resolution [35]. This method identifies regions of interest (ROI) in the m/z domain that contain potentially significant peaks, then performs continuous wavelet transform to discriminate true chromatographic peaks from noise [35]. For plant researchers dealing with highly complex samples containing both primary and specialized metabolites, this approach provides excellent sensitivity across concentration ranges that can vary by up to 9 orders of magnitude [34].

Figure 1: XCMS Pre-processing Workflow. The process begins with raw LC-MS data, undergoes core processing steps, and produces a peak table ready for statistical analysis.

MZmine: Modular and User-Friendly

MZmine employs a modular, workflow-oriented approach that allows users to construct custom pre-processing pipelines through a graphical user interface [37]. This flexibility makes it particularly valuable for plant metabolomics studies requiring non-standard processing approaches, such as those involving specialized metabolite classes or novel instrumentation [37] [38]. The platform's visualization capabilities enable researchers to inspect processing results at each step, providing immediate feedback on parameter optimization—a valuable feature when dealing with the diverse chemical characteristics of plant metabolites [38].

A distinctive feature of MZmine is its advanced support for mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) data, which is increasingly important in plant sciences for understanding spatial distributions of metabolites within tissues [34]. This capability allows researchers to correlate metabolite localization with physiological function, such as identifying defense compounds accumulated at infection sites or understanding spatial patterns in specialized metabolite production [34]. For plant researchers investigating tissue-specific metabolic responses to environmental stresses, this spatial dimension can provide crucial biological insights unavailable from bulk tissue extracts.

Figure 2: MZmine Modular Processing Pipeline. The workflow showcases the modular approach where each processing step can be independently configured and visualized.

MS-DIAL: Comprehensive MS/MS Focus

MS-DIAL distinguishes itself through its robust support for data-independent acquisition (DIA) and data-dependent acquisition (DDA) MS/MS data, providing particularly strong capabilities for metabolite identification [37] [2]. The platform incorporates an integrated retention time index system that improves alignment accuracy and supports the identification process, which is especially valuable for plant metabolomics where many compounds lack commercial standards [2]. Its ability to perform de novo spectral decomposition without relying exclusively on reference libraries makes it powerful for discovering novel plant specialized metabolites [2].

For plant lipidomics, MS-DIAL offers specialized lipid annotation based on the LIPID MAPS database, enabling comprehensive characterization of lipid molecular species [37] [2]. This capability is crucial for understanding plant membrane remodeling in response to abiotic stresses or analyzing lipid-based signaling molecules [34]. The software's four-dimensional alignment algorithm (m/z, retention time, MS/MS spectrum, and collision cross-section for ion mobility data) provides particularly confident annotation when analyzing complex plant extracts containing numerous structural isomers [2].

Table 2: Advanced Capabilities for Plant Metabolomics

| Capability | MS-DIAL | MZmine | XCMS | Value in Plant Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIA Data Processing | Excellent | Limited | Limited | Critical for comprehensive coverage of plant specialized metabolites |

| Lipid-Specific Annotation | Integrated | Modular | Via packages | Essential for plant stress physiology and membrane biology |

| Spectral Deconvolution | Advanced | Good | Basic | Vital for resolving complex plant metabolite mixtures |

| Retention Time Index | Integrated | Optional | Limited | Improves identification confidence across laboratories |

| Ion Mobility Support | Yes | Limited | Limited | Enhances isomer separation in complex plant extracts |

Experimental Protocols for Plant Metabolomics

Sample Preparation for Plant Tissues

Proper sample preparation is foundational to successful plant metabolomics studies. The protocol below is optimized for comprehensive metabolite extraction from diverse plant tissues [39] [40]:

Rapid Quenching: Immediately after collection, flash-freeze plant tissue in liquid nitrogen to arrest metabolic activity. Grind tissue to a fine powder under liquid nitrogen using a pre-chilled mortar and pestle [39] [40].

Comprehensive Metabolite Extraction: Weigh 100 mg of frozen powder into a pre-cooled microcentrifuge tube. Add 1 mL of cold (-20°C) methanol:chloroform:water extraction solvent (2.5:1:1 v/v/v) with 10 μL of internal standard mixture (e.g, stable isotope-labeled amino acids, fatty acids, and sugars for quality control) [39] [40].

Vortex and Sonicate: Vigorously vortex for 30 seconds, then sonicate in an ice-water bath for 15 minutes to ensure complete cell lysis and metabolite extraction.

Phase Separation: Centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C. Transfer the upper polar phase (methanol/water layer) to a new tube for polar metabolite analysis. Transfer the lower organic phase (chloroform layer) to a separate tube for lipid analysis [39].

Concentration and Reconstitution: Dry both fractions under a gentle nitrogen stream. Reconstitute polar fractions in 100 μL LC-MS grade water:methanol (95:5) and non-polar fractions in 100 μL isopropanol:acetonitrile (90:10) for LC-MS analysis [39] [40].

Data Pre-processing Protocol with Quality Control

Robust pre-processing requires careful quality control throughout the analytical workflow [35] [40]:

QC Sample Preparation: Create pooled quality control samples by combining equal aliquots from all experimental samples. Run QC samples at the beginning of the sequence, after every 6-10 experimental samples, and at the end to monitor instrument performance [35] [19].

Parameter Optimization for Plant Samples: For XCMS, optimize critical parameters using the IPO (Isotopologue Parameter Optimization) package. For MS-DIAL, use the retention time standard mixture to calibrate the index system. For MZmine, employ the batch processing mode to systematically test parameter sets [35] [38].

Data Filtering: Remove features with >30% relative standard deviation in QC samples and those with >80% missing values across biological samples. Apply signal correction based on QC samples using locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) or random forest correction [35] [19].

Figure 3: Quality Control Workflow for Plant Metabolomics. The diagram highlights the iterative quality assessment process with feedback loops to ensure data quality.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Item | Specification | Application in Plant Metabolomics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extraction Solvents | Methanol:Chloroform:Water | 2.5:1:1 v/v/v, HPLC grade with 0.1% formic acid | Biphasic extraction of polar and non-polar metabolites from plant tissues [39] |

| Internal Standards | Stable Isotope-Labeled Mix | 13C, 15N-labeled amino acids, fatty acids, sugars | Quality control, normalization, and retention time calibration [39] [40] |

| Reference Libraries | Plant-Specific Spectral Libraries | RefMetaPlant, PMhub, KNApSAcK | Annotation of plant specialized metabolites [2] |

| Quality Control | Pooled QC Sample | Equal aliquots from all experimental samples | Monitoring instrumental drift and technical variation [35] [40] |

| Retention Time Calibration | RT Index Standard Mixture | C8-C30 fatty acid methyl esters | Retention time normalization across sequences [2] |

Integrated Workflow for Plant Metabolite Discovery

The tremendous structural diversity of plant metabolites necessitates specialized approaches that address the annotation bottleneck [2]. The following integrated workflow combines the strengths of multiple pre-processing tools to maximize biological insights:

Initial Processing with MS-DIAL: Begin with MS-DIAL for comprehensive MS/MS data processing, leveraging its robust deconvolution algorithms and retention time index system to create an initial feature table with MS/MS annotations [37] [2].

Cross-Platform Validation with MZmine: Import results into MZmine for visual inspection and validation of challenging peaks, particularly those with low abundance or co-elution issues. Use MZmine's modular capabilities to refine peak boundaries and integration parameters [38].

Statistical Analysis with XCMS: For large-scale studies or complex experimental designs, utilize XCMS's powerful statistical framework for differential analysis, leveraging its seamless integration with the R ecosystem for advanced multivariate statistics and visualization [35] [37].

Identification-Free Analyses: For the >85% of features that remain unidentified, employ molecular networking, distance-based approaches, and information theory-based metrics to extract biological insights from global metabolic patterns without requiring complete annotation [2].

This integrated approach acknowledges that no single tool currently addresses all challenges in plant metabolomics, particularly given the vast unknown chemical space represented by plant specialized metabolism [2]. By strategically combining tools and incorporating both identification-dependent and identification-free analysis methods, plant researchers can maximize the biological insights gained from their metabolomics studies while acknowledging current technological limitations.